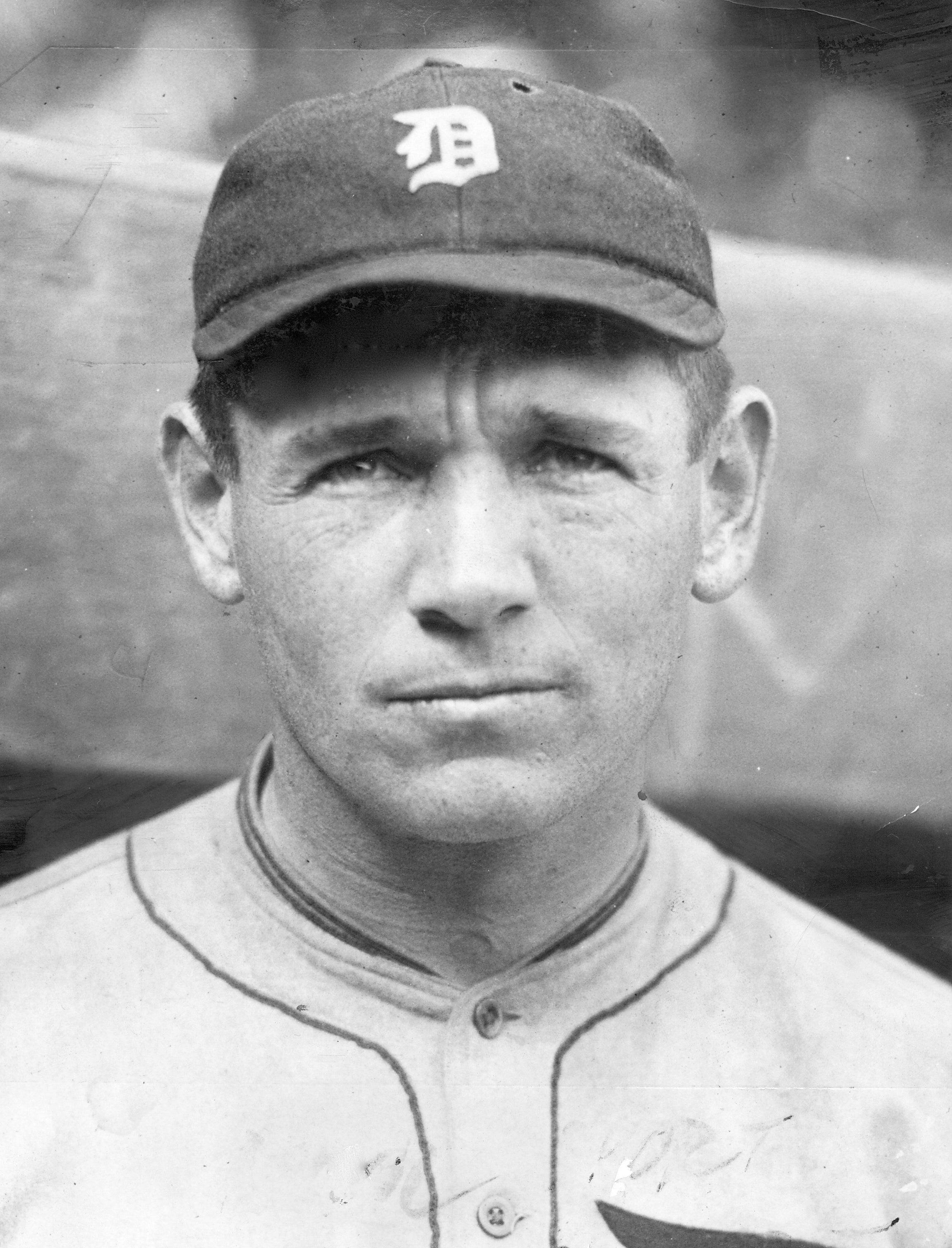

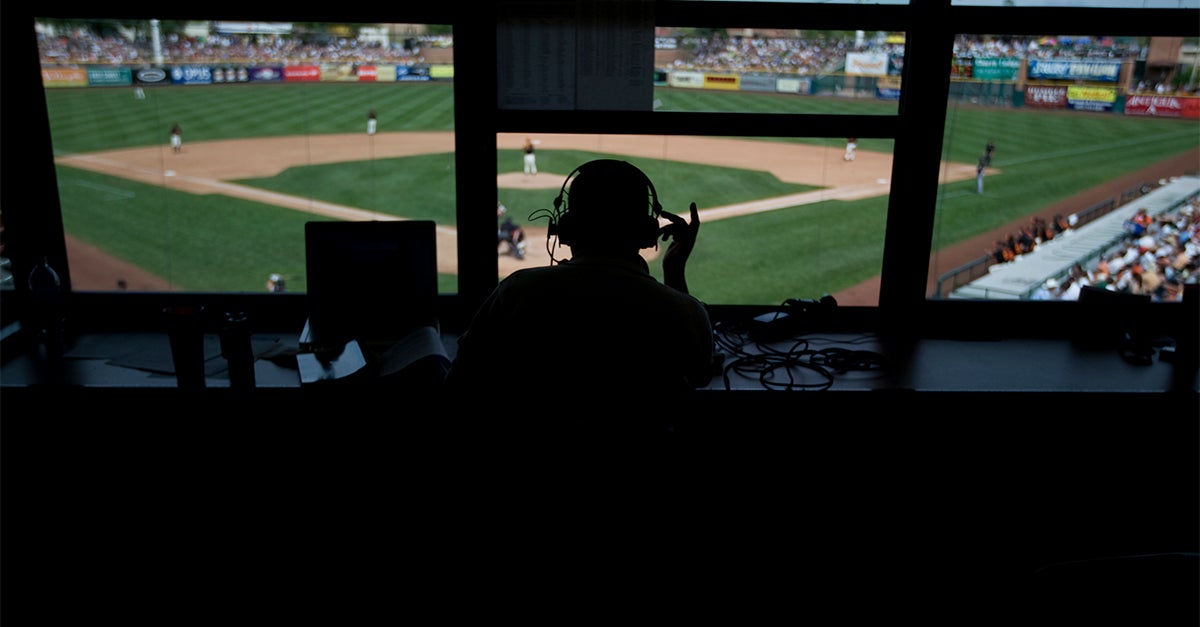

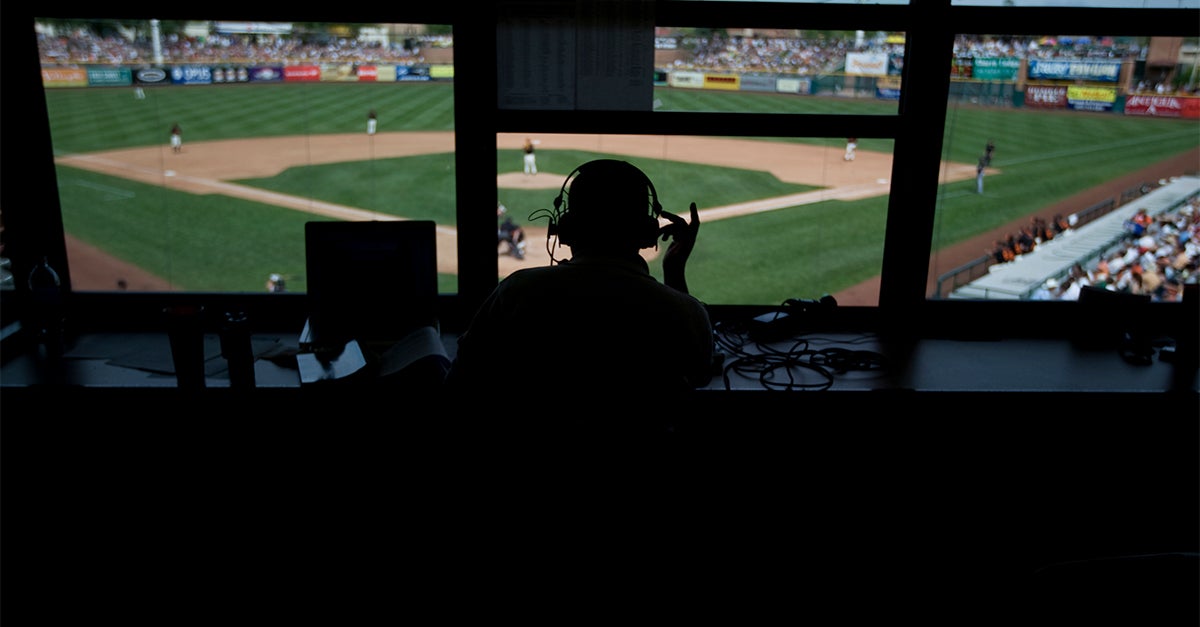

“His hearers, many novice fans, thoroughly understood his broadcasts.”

Tom Manning

Manning’s voice travelled beyond baseball, from golf courses and hockey rinks to tugboats and soap box derbies – where he once suffered two cracked ribs from a collision into his booth. Though he was known to be bombastic, Manning remained adept at translating the happenings of the field to his viewers.

“His hearers, many novice fans,” reported one newspaper writer, “thoroughly understood his broadcasts.”

Manning remained with NBC through 1938, when the Sporting News named him as its Announcer of the Year and praised his “uncanny ability to shoot from the hip.” In 1940, he shifted gears and became sports director for a Cleveland television news station. He returned for a final swan song with the Indians, pairing with Dudley for the 1956 season.

Upon his death in 1969, the Cleveland City Council named him as one of the “ten most important men” in the city’s history. He brought Indians baseball to the living room, and did it his way.

“I like to win big or lose big,” Manning once said. “But what’s the sense of losing small?”