Baseball in the land of the rising sun

Mizuno

The Knuckle Princess

Tokyo Little League

Tokyo Dome

Japan Baseball Hall of Fame

Baseball in Japan was introduced in 1872 by Horace Wilson, an American professor of English at Kaisei Gakko University (today known as Tokyo University), as we learned at the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame from Museum President Shinichi Hirose, Curator Takahiro Sekiguchi and Librarian Taku Chinone.

Exactly 20 years after the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown got its start, Japan’s Hall of Fame was born, opening in 1959 next to Korakuen Stadium where the Yomiuri Giants played before the Tokyo Dome was built. Today the museum is located in the Tokyo Dome. The museum’s mission is similar to ours: To promote the game of baseball by collecting, preserving and displaying artifacts, while also inducting baseball’s greatest contributors.

The exhibit galleries take visitors through the growth and history of the game in Japan since Wilson’s introduction of the sport. Artifacts from several American Hall of Famers who played exhibition games in Japan are on display, including a Mike Piazza bat and a Ken Griffey glove, as well as a bat used by Pudge Rodriguez, who will be inducted in Cooperstown in July. Artifacts from goodwill tours by American teams, dating back to the Reach All-Americans in 1908 to the modern day MLB All-Star tours, give Japanese fans a further glimpse into the equipment used by stars from the states. And hundreds of artifacts related to the greatest contributors in Japanese professional baseball, remind visitors of the historical accomplishments achieved since the sport became professional in the 1920s.

Amateur baseball in Japan is so prevalent and important that there’s an entire gallery dedicated to its story. “Naigai Baseball” is widely popular, and its story is told here. The white ball is made of very hard rubber and is hollow, similar to the old pink Spalding balls many of us played with in the 1960s and 70s. These soft baseballs in Japan are very popular and have been around since 1949.

There are high school and college tournaments played with the Naigai ball, not to mention a summer youth tournament sponsored my McDonald’s for the last 37 years, featuring 1,200 teams. Every level of amateur baseball, from Little League to the Cal Ripken World Series to the Women’s World Cup (we learned that Team Japan won five straight championships) to Olympic Championship teams to industrial teams are all represented in the Museum.

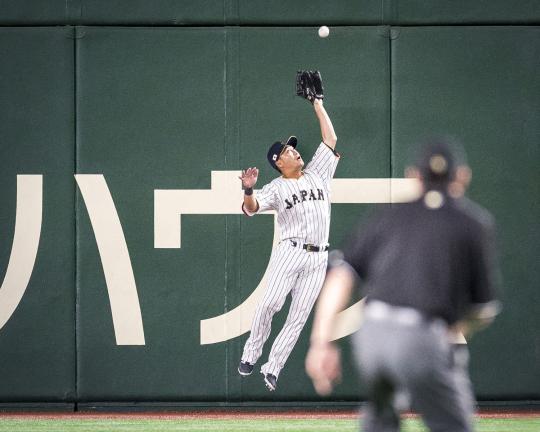

The Museum has a special exhibit gallery that in 2017 features the history of the WBC and Japan’s successes, with uniforms from all of the players from the winning teams displayed. And just like in Cooperstown, the Museum documents history as it unfolds, with the Final Out baseball from Japan’s win over Cuba in the Opening Game of pool play on exhibit in the Museum when its doors opened the next day, as well as the final out balls from all of their other wins in the 2017 tournament.

Like Cooperstown, the Hall of Fame also has a Library full of books, magazines and photographs. The oldest book in their collection was published in 1868 and is called “The Book of American Pastimes,” and is of course, about baseball. In total, the Library contains some 50,000 titles.

The tour concluded in the Museum’s vaunted Hall of Fame Gallery of Plaques. Whereas our Hall of Fame now has 317 members, the one in Japan includes 197 inductees. Like us, there are five Japanese inductees this year. There ceremony is held in July as well, but takes place before the All-Star Game as a pre-game ceremony. Our plaques are made from bronze – there’s are from wood and bronze. And a very cool new mobile app developed by the Museum enhances the fans’ experience, as by pointing their mobile devices at any of the plaques allows them to view videos of the inductees.

Of the 197 inductees, three are Americans. Wally Yonamine, a Nisei from Hawaii was the first in 1994, Horace Wilson, and Lefty O’Doul.

Over countless trips to Japan before and after World War II, O’Doul, a former major leaguer and long-time San Francisco Seals manager in the Pacific Coast League is credited with training players, helping to found the country’s first professional league, spreading the sport’s popularity, and serving as a good will ambassador for baseball. O’Doul, who hit .349 and won a pair National League batting titles during his brief career in the late 1920s and early 1930s, became one of Minor League Baseball’s most successful managers.