- Home

- Our Stories

- Filming Ted's Farewell

Filming Ted's Farewell

Camera Used to Shoot Ted Williams’ Final Home Run Lands in Cooperstown

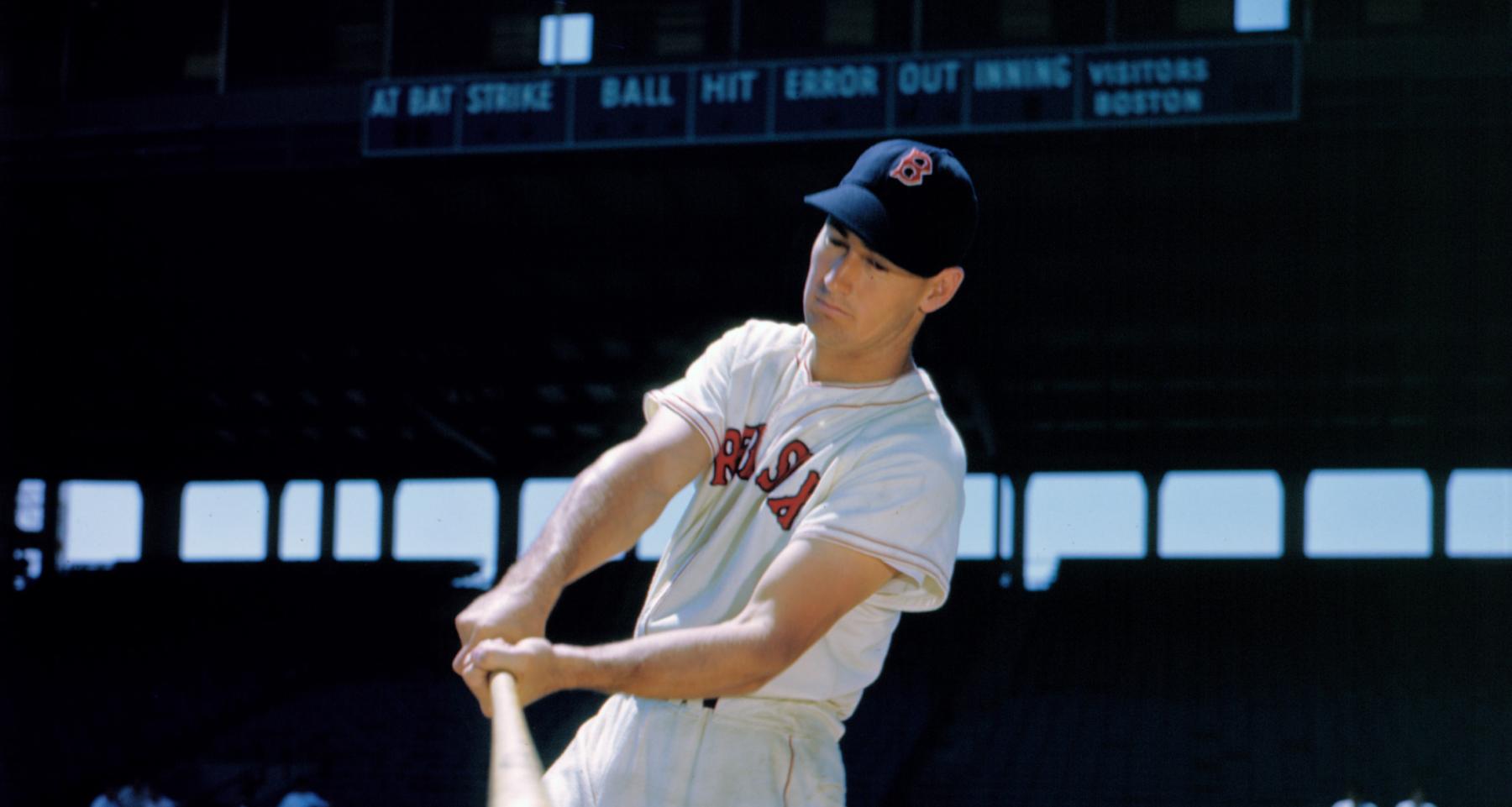

Stationed in the photographer’s box overlooking the first base side of Fenway Park on a cold and raw late September day, David Marlin knew he was in the right spot to capture baseball history.

It was Sept. 28, 1960, and just a few days earlier, Red Sox great Ted Williams announced his retirement, ending a 19-year career in Boston. Opting to skip the final series of the season against the Yankees in New York, Williams would take his final swings against Baltimore in front of the few and hardy Boston faithful on a Wednesday afternoon.

“That was the normal place for the photographers to work,” Marlin recalled in a recent interview, referring to Fenway Park’s overhanging high-shot boxes at first base and third base. “That day there was hardly anybody there (to cover the game). There might have been an AP photographer in the box with me. It was just a normal place for me to cover a left-handed pull hitter.”

Just shy of 10,500 fans attended the game, at the end of a 1960 season that saw the Sox finish 65-89. They watched as Williams was feted on the field before the contest and as he flied out twice after walking in his first plate appearance. With Boston facing a 4-2 deficit in the bottom of the eighth inning, Williams strode to the plate for the last time and hit his final home run – number 521 – off pitcher Jack Fisher and into the Red Sox bullpen in right-centerfield.

Marlin captured the historic moment on his Bell and Howell 16-millimeter Filmo camera, which is now in the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

All Comes Back to Ted

The operator would hold the heavy 14-pound camera and its variety of lenses, as opposed to using a tripod, while using a footswitch to operate the camera’s motor drive. Though not required, the footswitch made following the ball easier while holding the camera. A telephoto lens and the open-frame sports viewfinder allowed Marlin to track the ball from Williams’ bat to the bullpen.

For Marlin, who also has portraits hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., his lack of baseball skills led him to a career in photography. Growing up in the Boston area and attending Braves and Red Sox games, Marlin’s sandlot baseball exploits did not quite reach Hall of Fame level. But the 87-year-old Florida resident had an early interest in photography and extended that interest to sports.

“I was a photographer ever since I was a youngster. I loved being a photographer,” Marlin recounted. “I was the president of the camera club at Boston English High School, and I went to work in (portrait) studios.

“As a youngster, I used to go to Braves Field as part of the ‘Knot Hole Gang.’ Eventually, when I wound up getting a season pass from the Red Sox to cover baseball – that was terrific. I was back at Fenway Park. I didn’t have to sneak into the grandstand anymore.”

Ted Williams created this “heat map” in his book The Science of Hitting to indicate what he would hit against pitches thrown in each ball-wide area of the strike zone. The exhibit, located on the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s second floor, remains one of the most popular among Hall of Fame visitors. BL-853-2002 (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Following a stint in the United States Army during the Korean War, in which he developed his photography skills in the Signal Corps, Marlin returned to Boston and began working with a local television company. He would work in local television until 1962 when he began filming network stories for CBS, spending the next 25 years covering events throughout New England for CBS News.

“I covered the whole northeast. I did a lot of work with the Kennedys. A lot of politics – the presidential primaries in New Hampshire,” Marlin said, noting sporting events were also among his assignments.

“Baseball, hockey, basketball. You name it,” he continued. “Everything from tiddlywinks to horseshoe pitching. A lot of baseball, including All-Star Games and World Series.”

Even with all the events and people Marlin covered during his career, the subject keeps coming back to one individual: The Splendid Splinter.

“I worked with a lot of famous people and ballplayers and whatever, but even all these years later, I’m still asked about the most exciting events that I filmed,” Marlin said. “I flew over the Andrea Doria when it was sinking (off Nantucket), and (Maine Senator Edmund) Muskie (allegedly) crying in New Hampshire (during the 1972 presidential primaries) and Jack Kennedy at Hyannisport, but for sports fans, it’s always, ‘Tell us more about Ted Williams.’”

Legend Through the Lens

Marlin, who claims Williams left an indelible impression on him, did not just capture the Boston icon on film on the baseball diamond. He also spent time taking in Williams’ other love, sport fishing.

“I actually did two fishing films with Williams,” Marlin noted. “I traveled with him to document some of his fishing trips. He was a skilled sport fisherman, considered to be as good with the rod and the reel as with the bat.

“One of his best (baseball) seasons was 1957, and after that, I went down to Puerto Rico with him fishing for marlin. He caught plenty of fish, but I was the only ‘Marlin’ on the boat for 11 days.”

Yet as Williams rounded the bases in 1960 after his final home run, Marlin was surprised by the lack of a curtain call. Williams admitted in Ken Burns’ Baseball he was unlikely to perform one. The entire scene, and later scenes in the Red Sox clubhouse, were captured by Marlin on his camera.

“The Bell and Howell Filmo was a standard of the industry at that time,” said Marlin, who worked the game for United Press Movietone. “The 100 feet of film in that camera lasted two-and-three-quarters minutes. For local news, we would learn to go out and edit a story right in the camera. We would take it out of the camera, and the TV stations would develop it and play it right on the air.

“It was just about the time we started to cover everything in sound. Once we started filming everything in sound, we used the Filmo just to make cutaway shots of the crowd.”

Marlin described that it was important not to be winding the camera when filming actual events, such as the home run, lest the spring motor expire in the middle of a scene. Using the motor drive guaranteed that one would get key action from beginning to end.

Now his camera resides at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, where it will continue to tell multiple stories, including those of Williams and of the early days of baseball on television.

“I felt I could’ve sold it. There was a good market for it,” Marlin mentioned. “But I just felt that … it had a lot of good history to it. Why I kept it all these years, I don’t know, but I did. I said, ‘One of these days, I’m going to ask if anyone is interested.’”

Reaching out to Museum director of collections Susan Mackay, Marlin soon learned that Cooperstown was interested in the potential donation.

“It was my (lack of) baseball skills that led me into photography. As a ballplayer, I was never going to make it to the Hall of Fame,” he admitted. “But to think that my camera made it – well, that’s a pretty special feeling.”

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum