Seventy years later, Cannon Street All-Stars still adding to Little League legacy

Seventy years ago, a grave sporting injustice took place when a successful team of young boys were not allowed to play the National Pastime solely based on the color of their skin.

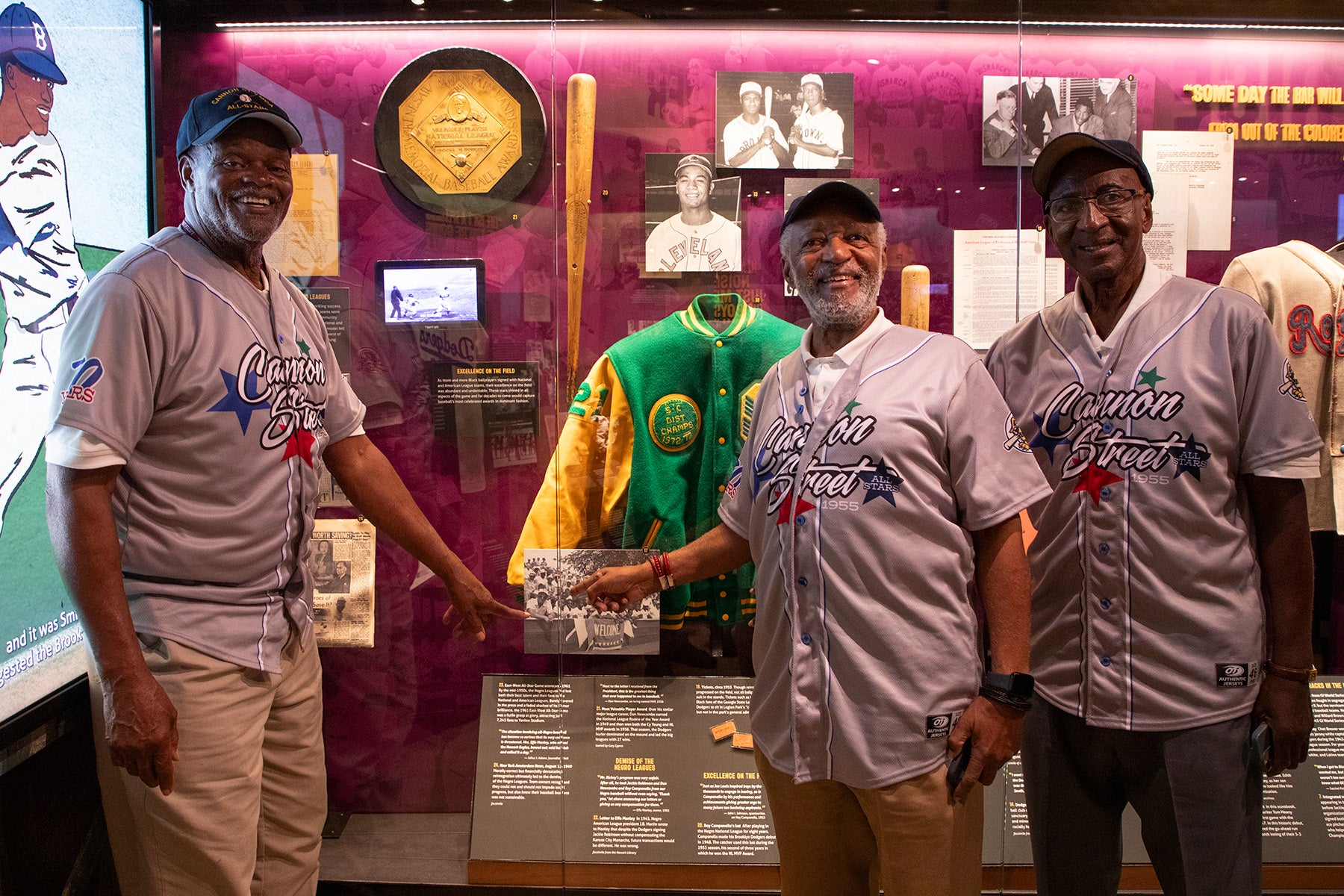

Recently, three of the affected Black youngsters – Leroy Major, David Middleton and John Rivers – told a rapt Voices of the Game audience in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Grandstand Theater of their experience dealing with the harmful effects of blatant racism at the tender age of 12. Now in their 80s, the trio vividly recalled this harrowing experience even though it took place seven decades ago.

Hall of Fame President Josh Rawitch, in introducing the panel, said, “It is truly an honor to have you gentlemen here with us today… We don't use that word honor very lightly.

“You are a part of baseball history. The three of you, your teammates, all of those who are part of the Cannon Street All-Stars are a part of baseball history, and that's what this whole institution, frankly, exists to do. We are here to preserve history, honor excellence and connect generations. And I really can't think of anybody who can do it better than these three sitting here with us today.”

In the summer of 1955, 14 boys from Charleston, S.C.’s Cannon Street YMCA Little League were looking forward to entering the Little League Tournament, along with thousands of other boys from around the globe. Back then, there were 62 chartered Little League programs in South Carolina, but the only league with African American players was the Cannon Street YMCA Little League. Until then, no South Carolina teams with Black players had entered the postseason tournament.

Each of the 61 other South Carolina leagues refused to play the Cannon Street YMCA team. Little League Baseball informed the other leagues that they would have to play, or forfeit.

Although the Cannon Street YMCA Little League played a full regular season of Little League ball and selected an all-star team, it was prevented by Little League policy from entering the playoffs because no other leagues in the state were willing to play.

Little League Baseball, citing its own policy banning racial discrimination, had ordered the other teams to play in the city tournament, but their managers and their coaches – not the players – steadfastly refused. Those team managers eventually seceded from Little League baseball, and they chose to form their own segregated league, the Dixie League. The Cannon Street All-Stars won by forfeit to play in the South Carolina state tournament, but the opposition teams again took the same approach as the opponents in Charleston. They would not play.

Little League President Peter McGovern then stepped in and announced that because the Cannon Street team did not win games on the field and advanced by forfeit, they could not move on to regional play. The organization cited a rule in its bylaws stating that clubs could only move on to regional play, and then from there, the Little League World Series, if you had won games on the field. That declaration officially ended the Cannon Street All-Stars’ season.

Like all Little League players their age, they knew the Little League World Series concluded in Williamsport, Pa. Despite not being able to advance in the tournament by way of its play on the field, Little League invited the Cannon Street team to Williamsport for the World Series. The team experienced all the things any other Little League World Series participant would, except it did not play a game.

In 2002, players from the 1955 Cannon Street All-Stars traveled to Williamsport to receive the South Carolina championship state banner that was not awarded to the team at the time.

Major, Middleton and Rivers, bedecked in Cannon Street All-Star jerseys and caps, said they just wanted to play the game. As the Cannon Street players walked off the Williamsport field, they heard spectators cheering loudly: “Let them play! Let them play!”

“We were ballplayers, like any ballplayer, no matter what the age, you just want to play ball. And we believed that we would play,” explained Rivers. “That was one of the things that I think was kind of embedded in our minds, that if we got to Williamsport, somehow, we’d be able to play. Now, I believe the adults, they knew better because of the technicalities. I didn't know about the intricacies of that, but we always believed we’d play until we got to Williamsport and the reality started.

“We stayed in the same dormitory with (white teams). We ate in the mess hall with them. The only difference between them and us was that we were an all-Black team. But what it was all about, even in that experience, was not about race. It was about baseball. These kids started talking about who’s the home run hitter here, who’s the best pitcher. And it’s interesting how if you let kids be kids, they didn’t care about race. Because if they let us play, those kids would have played us.”

Rivers would add, “Imagine getting on a bus and go travel 600-700 miles, go to the Little League World Series and then get back home and not say a word about it. Imagine that. Why not? It was traumatic. It was a traumatic experience.” On the team’s trip back to South Carolina from Williamsport, they got the news that the 14-year-old Emmett Till’s body was found in Mississippi, the African American youngster having been lynched.

“That really made us feel even more threatened, or just another negative feeling that we got, because now we’re 13-year-old, young, Black boys,” Rivers explained. “I got to a point after that story; I would not be on the same side of the street with a white woman. And so, the terrorism that was supposed to come from that, did work. It worked on many levels.”

Major explained he was not angry or shocked when he realized his team’s season would be ending prematurely.

“I was not because my parents did a good job of shielding me from knowing anything about the politics of what was going on,” he said. “That was beautiful, because kids should not be involved.

“Now, I went to a school and spoke to some of the young kids, and a little girl made me cry, because I never thought of it that way before. She said, ‘You mean to tell me that adults stole your dream?’ And I said, ‘Wow.’ It hit me so hard. I started crying right there in front of them.”

Middleton wanted to play in Williamsport because he knew his team was good.

“I wanted to play ball. And the simple reason was, we were good,” he said. “We had this opportunity to come to Williamsport. We left Charleston… but we couldn’t wait until we got to the park. And we got to the park. All we wanted to do was play ball. And so, when we had a chance to go on the field and loosen up, we were so excited. That’s the biggest reason for coming to Williamsport, Penn.

“And we knew we could win for what we had. So, we went on the field and all of a sudden, we heard an announcement that team from Charleston, South Carolina, won’t be able to play ball. And that was really hard on me, and I started crying. It really hurt because all we wanted to do was play ball, and we had a team knowing we would win a championship. It really hurts to this day. I'm 81 years old now, and it still hurts.”

Rivers, though limited contractually to what he could say, did confirm the Cannon Street All-Stars story has been optioned for a feature film they hope will be available on a Disney platform in 2026.

The trip to Cooperstown for the Cannon Street team members was only a stop along the way as the traveling party heads to Williamsport to be honored at the Little League World Series on Sunday. A team that made history without playing a game.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum