- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Greg Minton

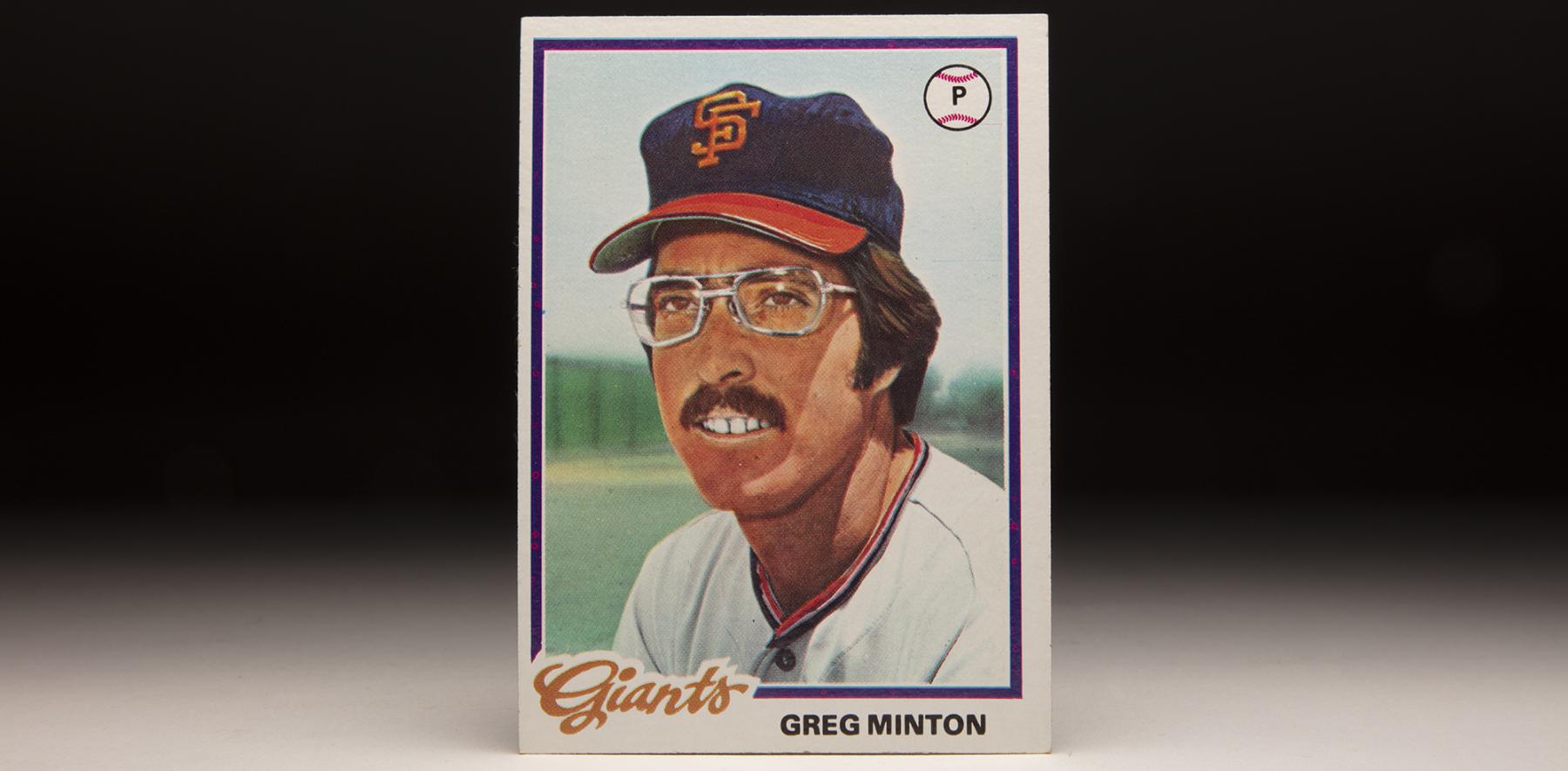

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Greg Minton

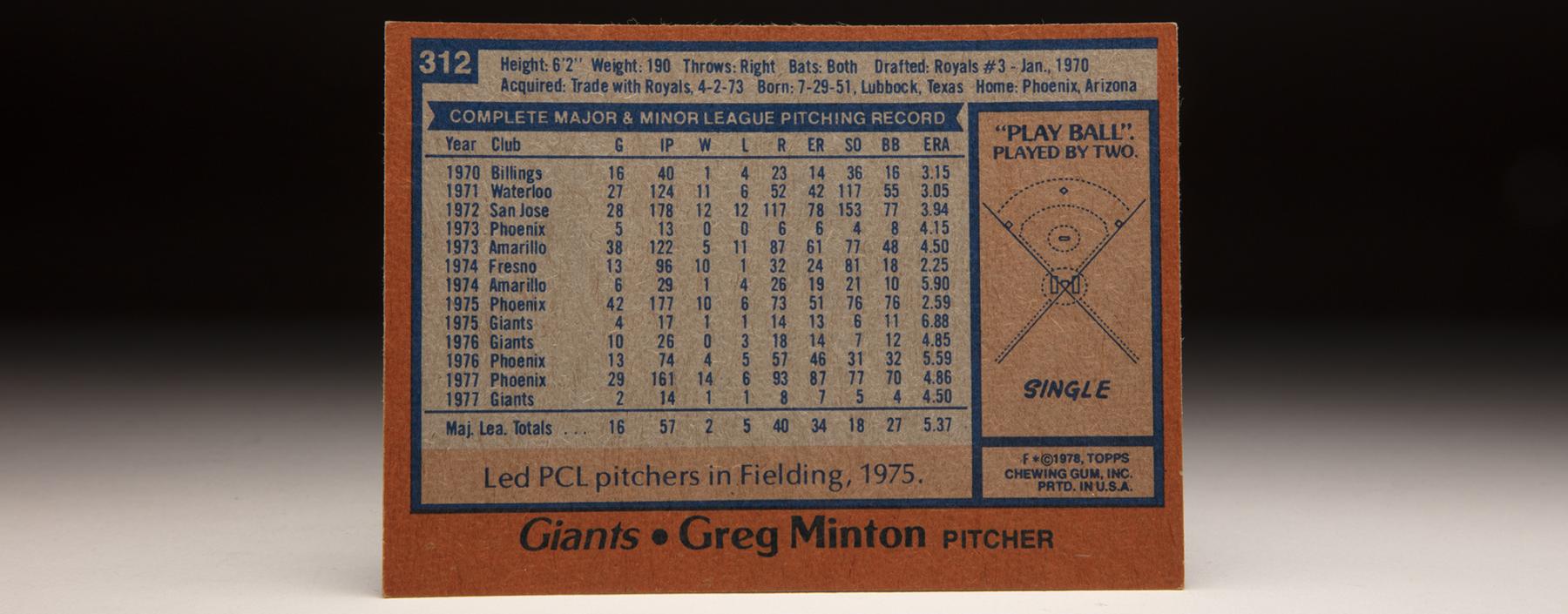

Greg Minton pitched 16 seasons in the big leagues, retiring with 710 appearances and 150 saves – good for 30th and 15th, respectively, on those all-time lists when he left the game.

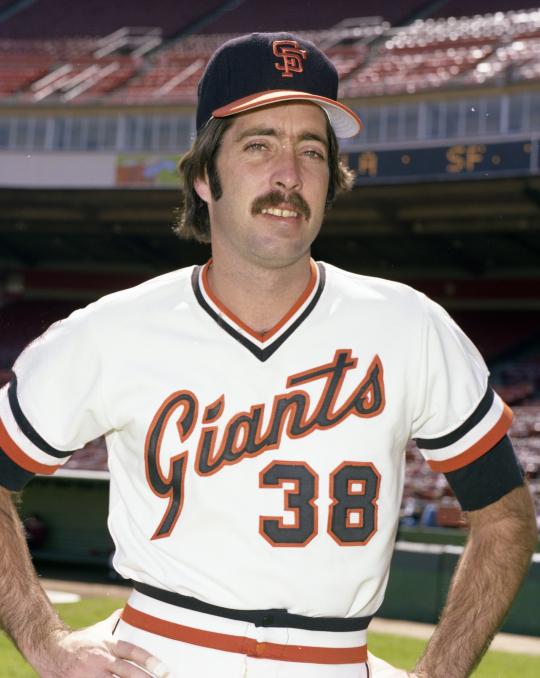

But for baseball card enthusiasts, Minton is probably best remembered for his 1978 Topps portrait.

One of a handful of totally airbrushed cards over the years, Minton’s likeness – or lack of one – in that set stands out to this day. Produced in all probability because Topps lacked a color photo of Minton, the card seems to present an almost cartoonish image of the right-hander.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Opposing hitters, however, found nothing funny about the Giants’ ace, who was one of the most durable and consistent relievers of his era.

Born July 29, 1951, in Lubbock, Texas, Minton was raised in Del Mar, Calif., and began showing up regularly in local papers by the time he was 17. Growing into his 6-foot-2 frame in high school, Minton dominated as a fastball pitcher and was also a gifted basketball player at San Dieguito High School in northern San Diego County. Like most of his peers, Minton spent countless days surfing at the beach.

Minton authored a perfect game as a senior but was not selected in the 1969 MLB Draft and instead enrolled at San Diego Mesa College, a community college founded by the San Diego City School District. Married at age 17, Minton got his shot in pro ball when the Royals selected him in the third round of the 1970 January MLB Draft – a process that was specifically put in place to secure junior college players or four-year college players who graduated in December.

Minton reported to Billings of the Pioneer League in 1970, posting a 1-4 record with a 5.18 ERA. He moved up to Class A Waterloo of the Midwest League in 1971, going 11-6, then made 28 starts with Class A San Jose of the California League in 1972, striking out 153 batters in 178 innings.

On April 2, 1973 – just three days before the season opener – the Royals traded Minton to the Giants in exchange for catcher Fran Healy. Minton was assigned to Triple-A Phoenix but spent most of the season with Double-A Amarillo, where he was 5-11 with a 4.50 ERA.

“I had no idea I was going to be traded,” Minton told the Arizona Republic immediately following the deal. “I had just found out I’d made Kansas City’s Triple-A Club, Omaha, when they called me in and told me about the deal. It’s been quite an adjustment.”

“We originally figured on sending him to Amarillo,” Phoenix Giants general manager Rosy Ryan told the Arizona Republic. “But I think we want to see more of him. This kid has good stuff.”

But in 1974, the Giants sent Minton all the way back to Class A Fresno, where he was 10-1 with a 2.25 ERA before earning a return trip to Amarillo. He finished the season with a combined mark of 11-5 with a 3.10 ERA over 19 starts.

“This is the first time in a long time that pitching has been fun,” Minton told the Fresno Bee during the 1974 campaign.

Advancing back to Triple-A Phoenix in 1975, Minton was 10-6 with a 2.59 ERA as a starter and reliever before debuting in the big leagues as a September call-up, making four appearances for the Giants down the stretch. Thus began a four-season odyssey for Minton, who regularly shuttled between the majors and Triple-A in 1976, 1977 and 1978 – never making more than 11 appearances for the Giants in any of those years while spending most of his time in Phoenix as a starting pitcher.

His 1978 Topps card appeared that spring, and that set also featured an airbrushed card depicting Red Sox pitcher Mike Paxton. But while Paxton’s card looked somewhat realistic, Minton’s caused most collectors to do a doubletake when they shuffled through their cards while hunting for the stick of chewing gum.

Meanwhile, in Spring Training of 1979, Minton’s career path was altered by what appeared to be an unwelcome injury.

“The last day of Spring Training in 1979, I was pitching to Bill Buckner of the Cubs and jammed him real good,” Minton told the Newspaper Enterprise Association. “He hit a little topper toward second base. I dove, rolled over, caught the ball on my rear end and got the guy – but I felt a twinge in my left knee. The very next pitch to the next batter just blew out all the cartilage.”

A knee operation followed, and when Minton returned he shortened his stride to protect the left knee during his follow through. Throwing batting practice to catcher Mike Sadek, Minton found that the shortened stride produced a wicked sinker.

“The ball’s going straight down,” Sadek said.

“Somewhere, because of that knee operation and the shortened stride, my delivery started doing tricks,” Minton told NEA. “It left me with a good pitch that goes straight down at 92 miles per hour – and that nobody else throws. I’d always been a power pitcher, but until then it was straight as an arrow.”

Minton’s knee surgery delayed his 1979 debut until June 1. After a rough couple outings, he embarked on a stretch where he allowed an earned run in one outing over a 19-game period. He closed the season with 11 straight appearances without an earned run and finished with a 4-3 record, four saves and a 1.81 ERA over 46 games. In 26 games at Candlestick Park, Minton had a 0.45 ERA and allowed just 23 hits in 40 innings.

“Last year things fell into place for me and I got some lucky breaks,” Minton told the San Francisco Examiner in Spring Training of 1980. “This year I think I have even more to prove.

“Until (opposing batters) prove to me they can hit my good sinking fastball, I’m going to use it.”

Giants manager Dave Bristol used Minton as his primary closer in 1980, and Minton went 4-6 with 19 saves and a 2.46 ERA over 68 games. Just like in 1979, Minton did not allow a home run all season – a stretch that dated back to Sept. 6, 1978, when the Dodgers’ Joe Ferguson took Minton deep before Minton had discovered his sinking fastball.

In 1981, Minton led all NL pitchers with 44 games finished and went 4-5 with 21 saves and a 2.88 ERA, earning votes in the National League Most Valuable Player Award polling. Once again, he did not allow a home run.

The homerless streak continued through the first nine games of the 1982 season before the Mets’ John Stearns homered off Minton on May 2 at Candlestick Park. It had been 269.1 innings since Minton allowed a home run – the longest span in baseball history (in terms of games pitched) and a record that still stands.

“It wasn’t a record I had been thinking about much because it wasn’t one I was going after,” Minton told the Oakland Tribune. “I’m a sinkerball pitcher and you’re not supposed to give up homers if you keep the ball low.

“But I got a fastball up and in the strike zone to Stearns and he hit it well. I thought about tackling him as he rounded third, but then I remembered that he’s strong and used to be a defensive back.”

Minton had already developed a reputation as one of the game’s great characters, earning the nickname “Moon Man” for his comments, pranks and eccentric behavior – including hang gliding during a Giants road trip to San Diego.

“I’m not the kind of flake who’s going to sit on birthday cakes nude,” Minton told NEA, referring to an infamous stunt by another unconventional reliever, Sparky Lyle. “But I do think, in general, different than other people. It carries over into my baseball.

“When I get into a game, all I do is say to the hitter: ‘You’re very good. I’m very good. Here we go, hard and low, one on one.’”

Minton finished the 1982 season with a 10-4 record in 78 games, including an NL-best 66 games finished. He posted a 1.83 ERA, saved 30 games, finished sixth in the NL Cy Young Award voting and eighth in the NL MVP vote.

Following the 1982 season, Minton signed a five-year deal worth $3.75 million, with incentives that could have been worth $2.25 million more. It made him one of the highest paid relievers in the game.

“The first time I saw the numbers of the contract was when I sat down to sign it,” Minton told McClatchy News Service. “At first, I couldn’t sign. My hand was shaking too much.

“Four years ago, I was a pitcher going to be sent down to the minor leagues for the third and last time. Instead, I injured my knee, developed a sinker and signed a large contract. If that isn’t Moon Man luck, I don’t know what is.”

Minton could not duplicate his 1982 season the following year, going 7-11 with 22 saves and a 3.54 ERA while walking more batters (47) than he struck out (38). The 1984 and 1985 seasons looked much the same, with Minton posting a combined 9-13 record with a total of 23 saves (19 coming in 1984) while walking more batters than he fanned each year.

Giants manager Frank Robinson split the closer duties between Minton and left-hander Gary Lavelle in 1983 and 1984, and by 1985 Scott Garrelts had supplanted Minton as the team’s stopper. He battled an early-season elbow injury in ’85 and finished the year with a 5-4 record and four saves in 68 games.

In 1986, Minton appeared in just 48 games and went 4-4 with a 3.93 ERA and five saves. The Giants’ fans at Candlestick Park regularly expressed their disappointment.

“Popular isn’t one of the words in the vocabulary anymore,” Minton told the Reno Gazette-Journal following the 1986 season. “If I wasn’t giving 110 percent, I could understand it. That’s what really hurt.

“’This is the best I can do, folks.’”

Minton entered the final season of his contract expecting to be traded. The Giants, en route to a surprising National League West title, found no takers, however. They released Minton on May 28 after he appeared in just 15 games.

But the Angels gave Minton a chance a few days later, and he recaptured some of his old form by going 5-4 with 10 saves and a 3.08 ERA – finishing the season with a respectable combined mark of 6-4, 11 saves and a 3.17 ERA over 56 games.

Working as a set-up man for Bryan Harvey in 1988, Minton battled arm and knee problems but still went 4-5 with seven saves and a 2.85 ERA in 44 games. He was even better in 1989, posting a 2.20 ERA over 62 games while going 4-3 with eight saves.

“He’s been a premier closing pitcher in his time,” Angels pitching coach Marcel Lachemann told the Los Angeles Times during the 1989 season. “He helps the younger pitchers like Harvey. He knows his role.”

But the wear and tear of throwing the sinker unloosed bone chips in Minton’s arm in 1990, and after four games – where he permitted no runs – he underwent surgery. He pitched in just seven games the rest of the year and would not pitch in the big leagues again.

“I’ve pitched in 708 more games than I thought I would,” Minton said near the end of the 1990 season when he was headed for retirement.

Minton finished with a 59-65 record, 150 saves and a 3.10 ERA over 710 games. He allowed just 43 homers over 16 seasons, an average of 0.3 home runs per nine innings pitched. Of all pitchers with at least 1,000 innings worked in the Expansion Era (post 1960), Minton’s average of 0.3 homers per nine innings pitched is unmatched.

But for one of the most effective relievers of his era, Minton may be best remembered for his offbeat personality – and his unique 1978 baseball card.

“I take very few things seriously,” Minton told McClatchy News Service. “If some people are put off by what they call flippant, I can’t help that. Someone will like it.

“I’m not a jokester. I just do things that come to me.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum