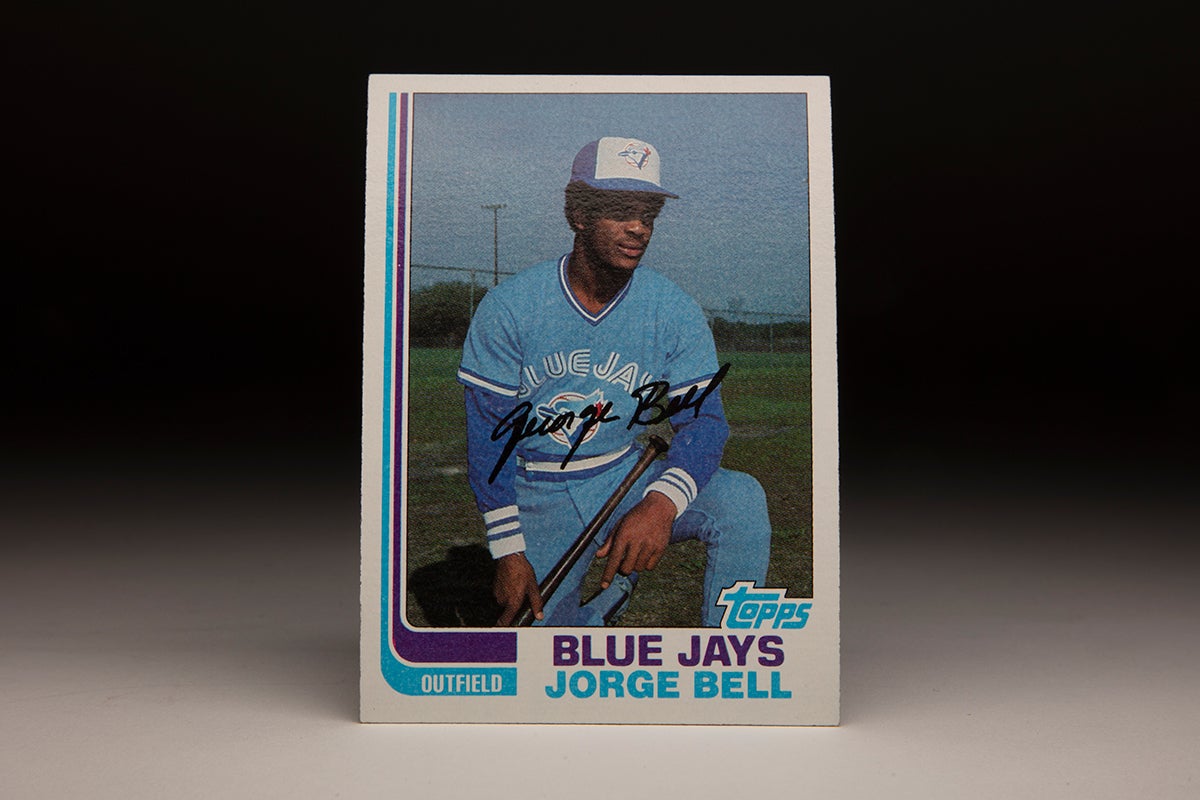

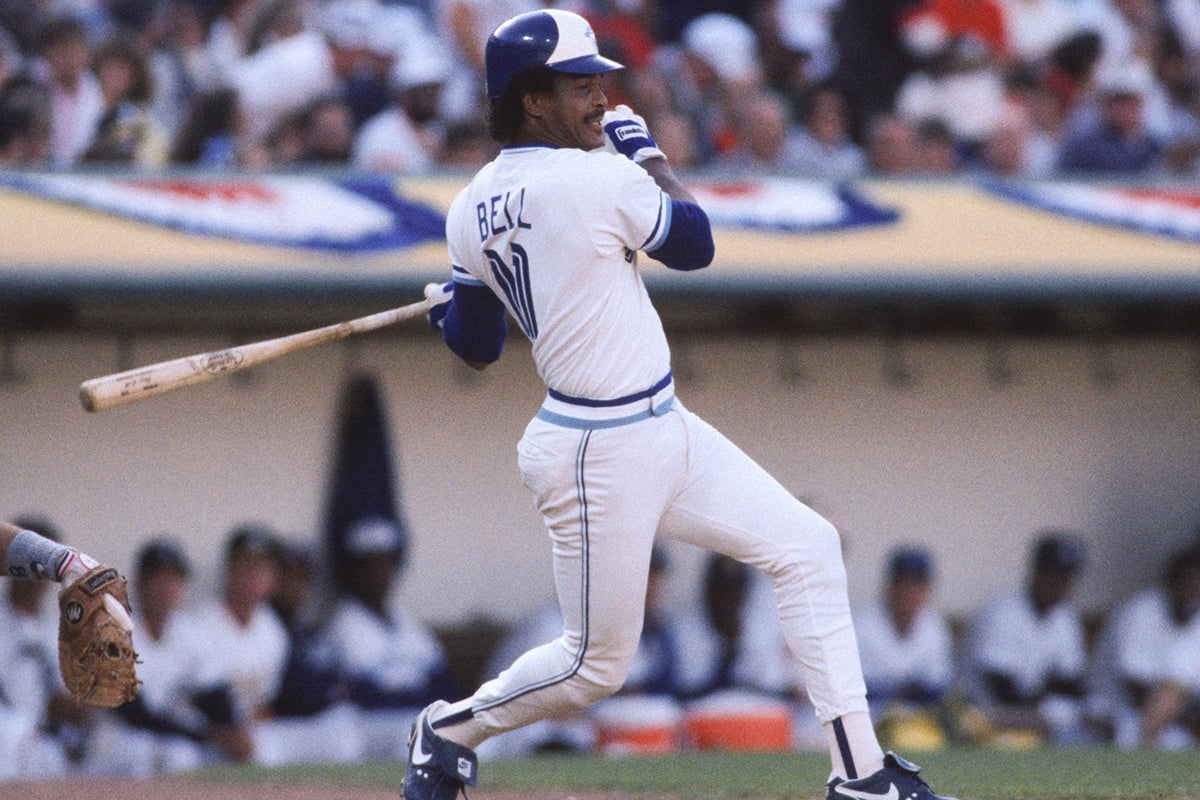

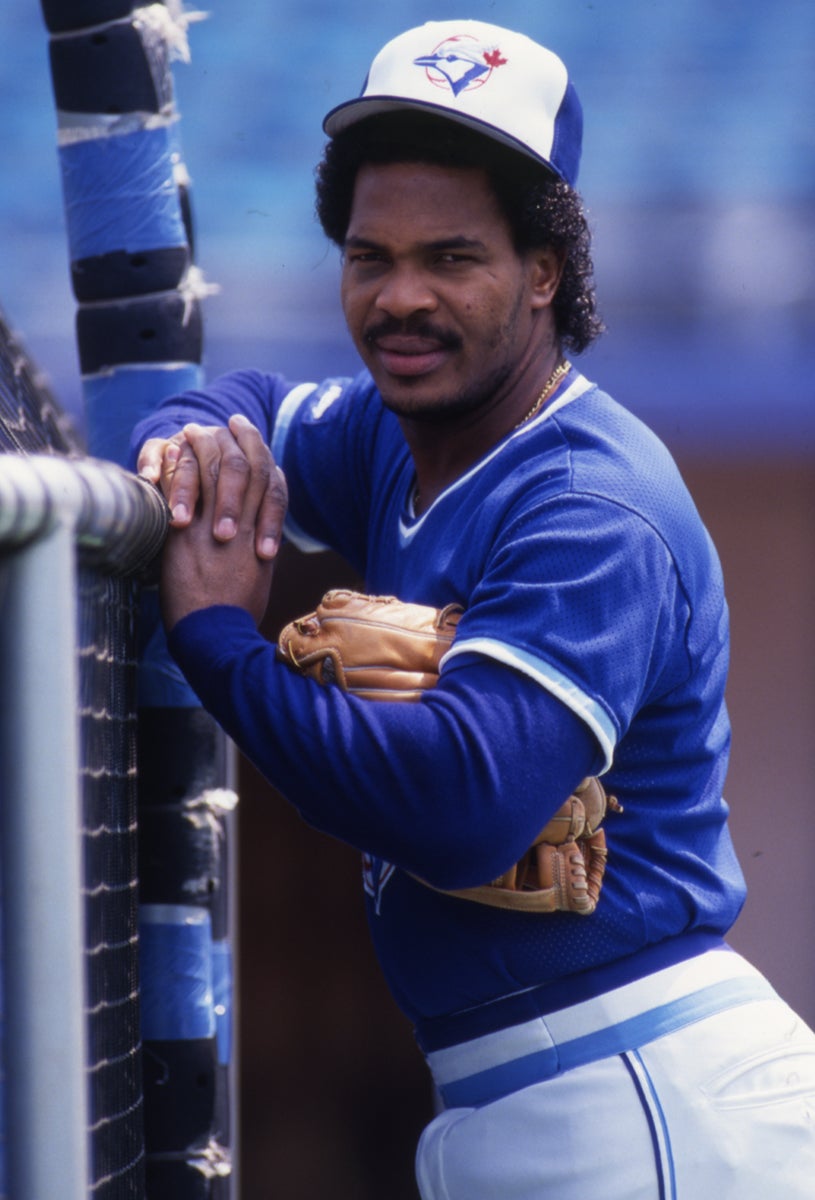

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps George Bell

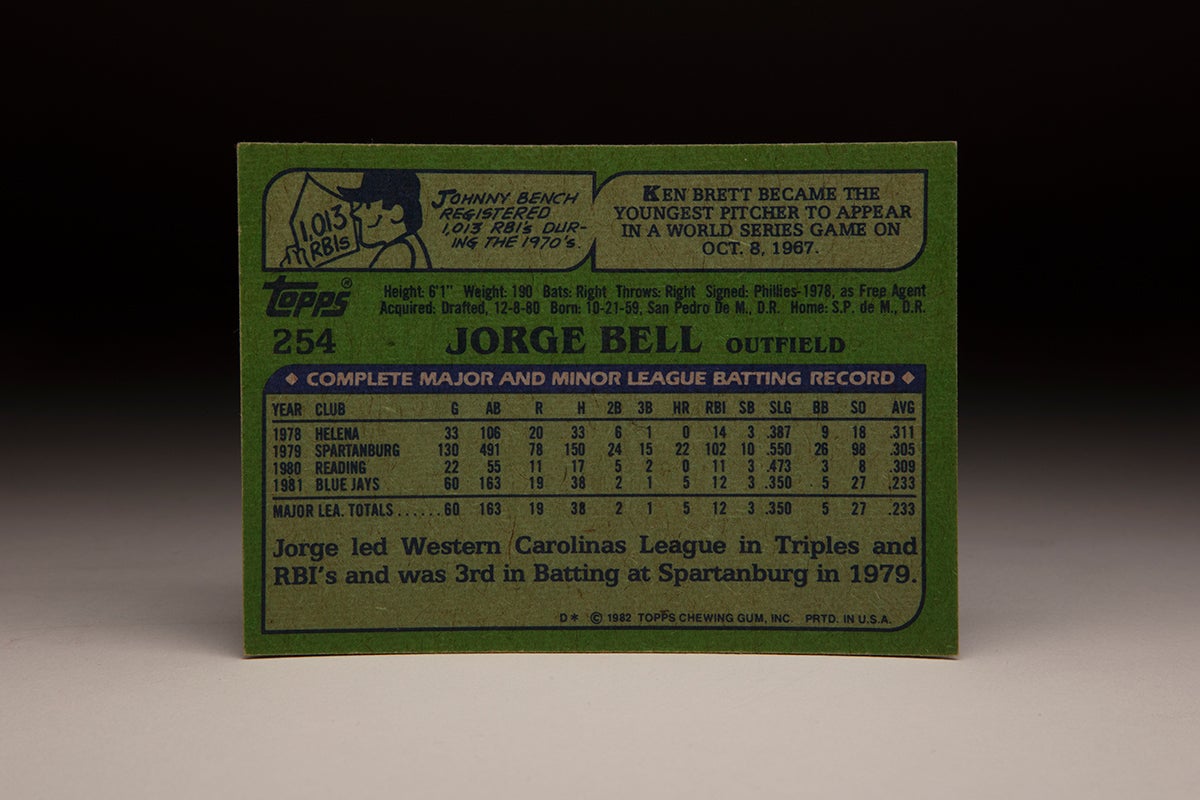

George Bell was introduced to card collectors – on each of the Topps, Donruss and Fleer sets in 1982 – as “Jorge” Bell. The misnomer would continue through several seasons, creating confusion surrounding the talented outfielder.

But once Bell won the 1987 American League Most Valuable Player Award, there was no mistaking him for anyone but one of the best players in the game.

Born Oct. 21, 1959, in Sante Fe, Dominican Republic – located within a short walk of the city limits of San Pedro de Macoris – Bell was the eldest of five children. His father, George Vinicio Bell, worked on the railroad and his mother operated a restaurant.

“We had to work hard for everything,” Bell told the Toronto Star in early 1987. “I came from a poor family, but we had a lot of things. We had three meals a day. We went to school – my father (could) afford it. But it was not easy for my dad.”

Like so many others in his native country, Bell grew up playing baseball and hoping to impress big league scouts. On March 7, 1978, he signed with the Phillies for a $4,000 bonus and came to America, where the Phillies assigned him to Helena of the Pioneer League.

“That was terrible,” Bell told the Star of the 1978 season, when he hit .311 in 33 games. “In rookie ball and (Class A) ball, I was learning how to start being a man. I was mom and daddy’s son. They gave me everything. As soon as I left, I was on my own. I was like a fish out of water.”

Bell’s talent, however, allowed him to adjust quickly on the field. In 1979, he hit .306 with 22 home runs and 102 RBI in 130 games for Class A Spartanburg in the Western Carolinas League despite racial challenges.

“When you play in South Carolina and Tennessee, they don’t treat Black players and Latin players right,” Bell told the Star. “I think that’s completely wrong. You are a professional no matter what skin color you have.”

Bell played in only 22 games with Double-A Reading in 1980 due to a back injury. But by the end of the season, Bell had recovered and suited up in the Dominican Winter League, where the Phillies hoped he would not be seen.

Blue Jays scout Al LaMacchia, however, noticed Bell – who was playing in “B” games that only took place in the morning.

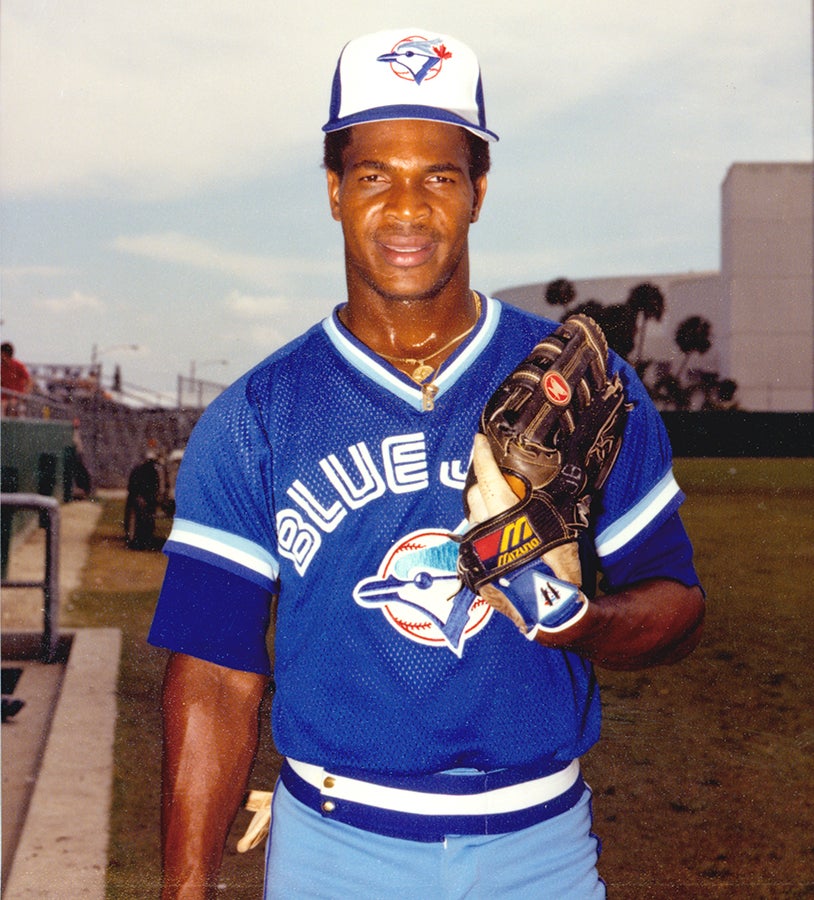

“I saw him swing the bat well, run, throw and slide,” LaMacchia told the Star. “He’s got all the skills: He can throw, he can run, he can hit and he can hit with power.”

On Dec. 8, 1980, the Blue Jays took Bell in the Rule 5 Draft.

“I can’t believe the Phillies wouldn’t protect him (from the Draft),” Joe Buzas, the Reading Phillies’ owner, told the Star. “I’ve been in the business for 40 years and I haven’t seen anyone like him. I had Jim Rice for his first two years in baseball and Bell has more potential. I had Rick Burleson and Fred Lynn, too, and none of them looked as good as this kid does.”

As a Rule 5 pick, Bell had to be kept on the Blue Jays’ roster for the entire 1981 season or be offered back to the Phillies. He made his big league debut on April 9 against the Tigers in Detroit, entering the game in the eighth inning as a pinch-runner for John Mayberry and then remaining in the contest as the left fielder.

Bell got his first start and first hit on April 22 against the Brewers and saw regular time in left field and right field the rest of the season, finishing with a .233 batting average and five home runs in 60 games en route to an eighth place finish in the American League Rookie of the Year voting.

Free to send Bell back to the minors for more seasoning, the Blue Jays assigned Bell to Triple-A Syracuse in 1982. But he played in only 37 games – hitting .200 – thanks to a knee injury and then a fractured jaw suffered when he was hit by a pitch.

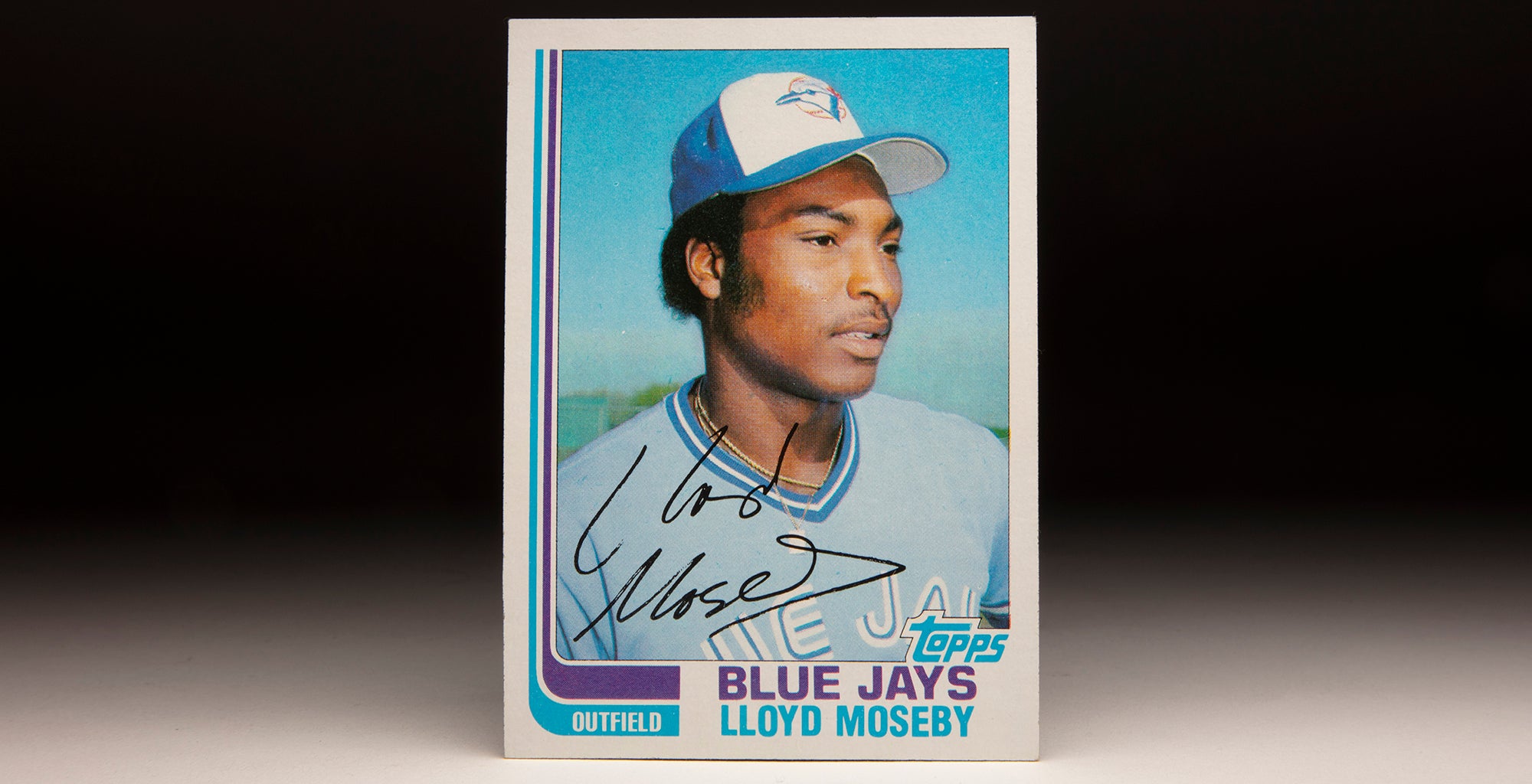

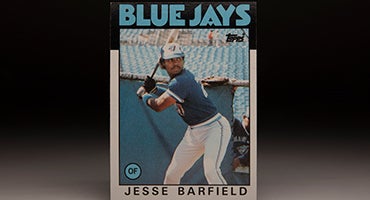

Bell returned to Syracuse to start the 1983 season and was hitting .271 with 15 homers and 59 RBI in 85 games when the Blue Jays waived Hosken Powell and recalled Bell. He played in 39 games the rest of the year, batting .268 with two homers and 17 RBI while fighting for a spot in a Toronto lineup that included outfielders Jesse Barfield, Lloyd Moseby, Dave Collins and Barry Bonnell.

“It’s very different from being in Triple-A where you play every day,” Bell told the Associated Press after a three-hit game on Sept. 6 vs. the Angels. “Here I sit on the bench and if they want to use me, I’m ready. When you’re in the lineup, you have to play 100 percent because it’s the only chance you have to play.”

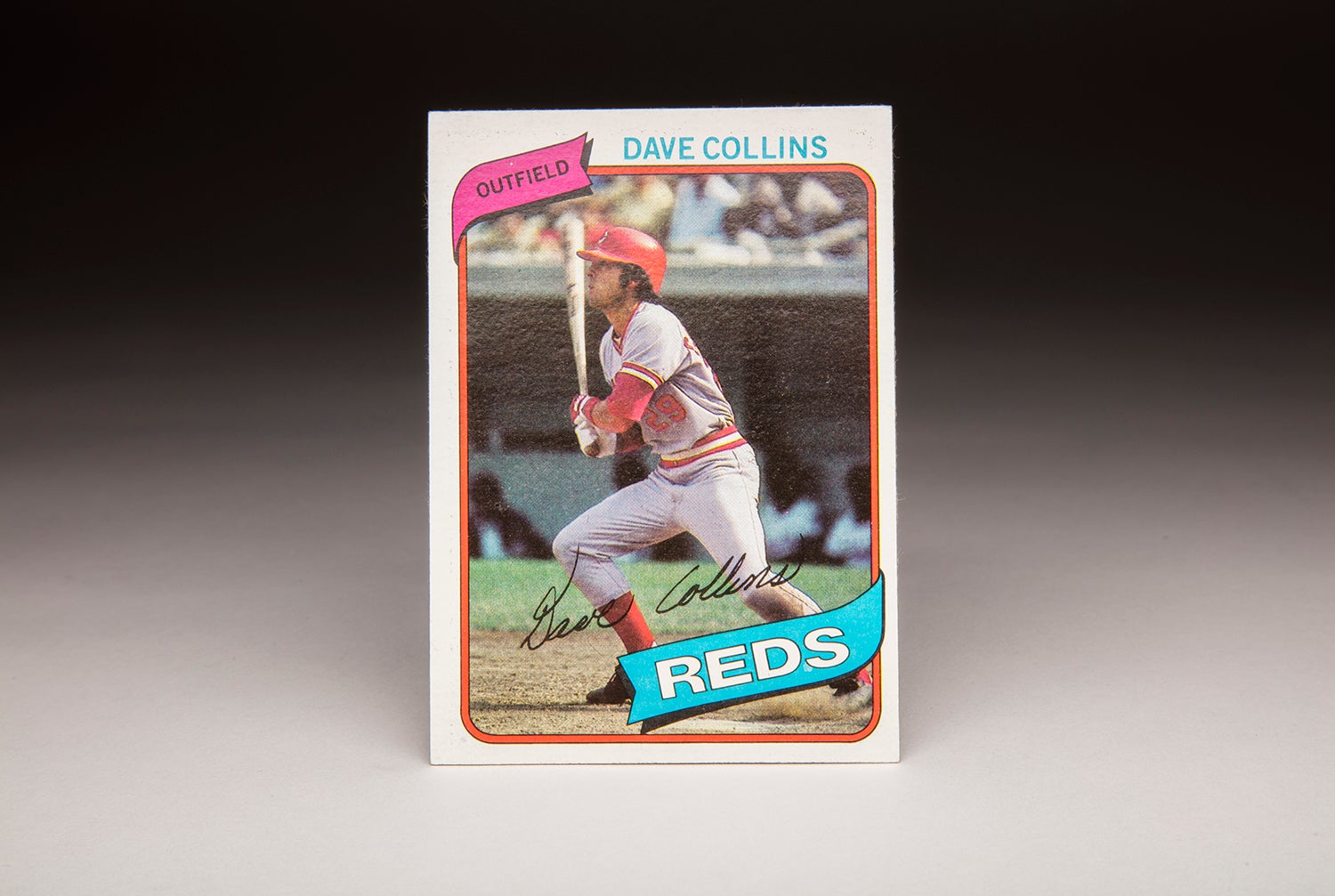

Following the 1983 season, the Blue Jays traded Bonnell to the Mariners. Bell took advantage of the opportunity by pounding the ball in Spring Training and stepped into the starting lineup, batting .292 in 159 games with 87 RBI and team-high totals in doubles (39) and home runs (26) despite splitting his time between left field and right field – moving back and forth as Collins platooned with Barfield in an arrangement Bell did not appreciate.

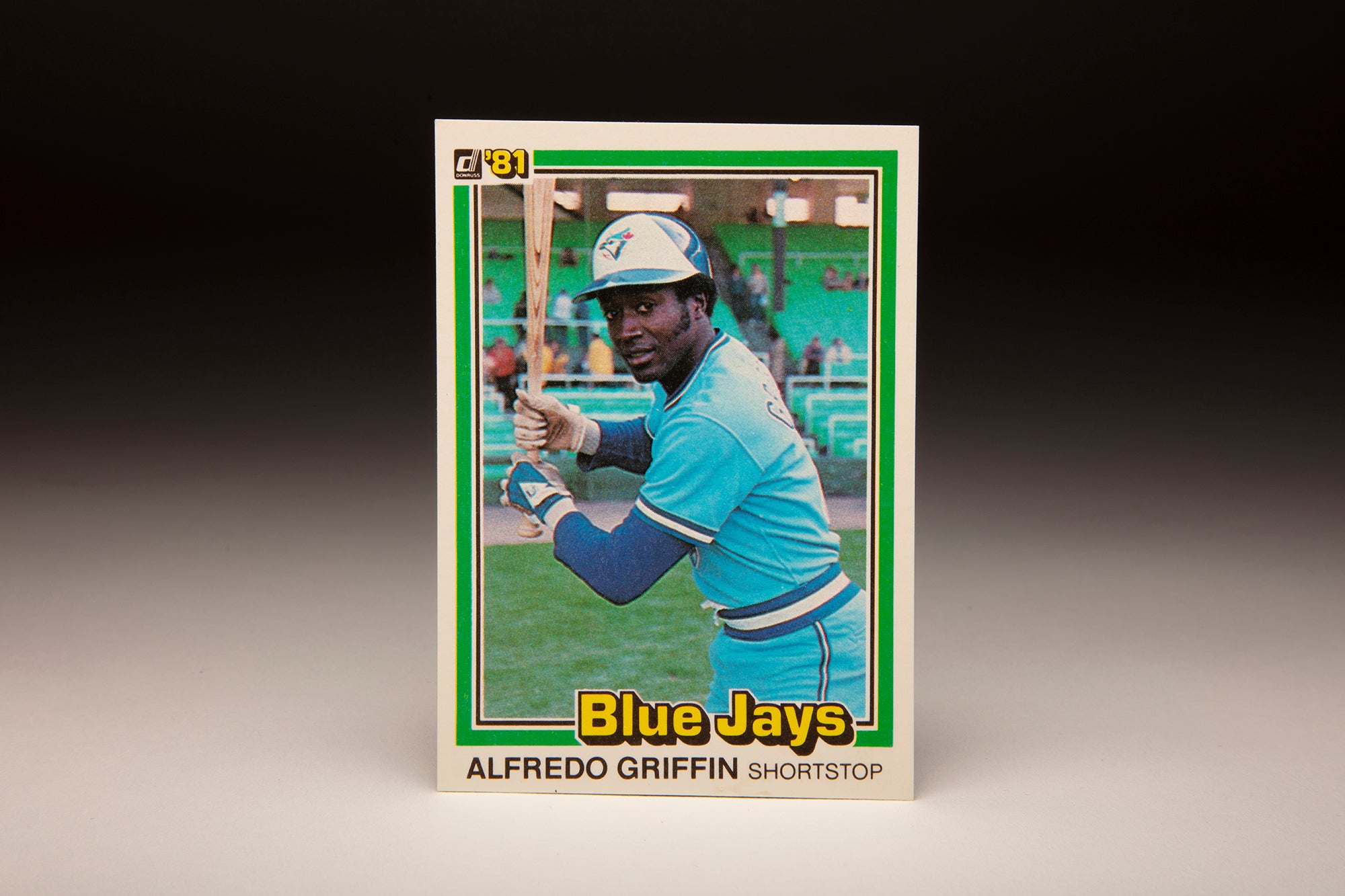

Bell finished 19th in the AL Most Valuable Player voting following the 1984 campaign – and Toronto now had a young outfield in Bell, Moseby and Barfield that was the envy of every team in baseball. And on Dec. 8, 1984, Toronto sent Collins and Alfredo Griffin to the Athletics in exchange for Bill Caudill, leaving Bell with the left field job to himself.

“What I like to do is go home at night, relax and think about what I’m going to be doing the next day,” Bell told the Star in the spring of 1985. “So when I was changing so much, it was hard for me to concentrate that way. Left field and right field are two totally different situations, you know.”

Bell virtually duplicated his 1984 numbers in 1985, totaling 28 homers and 95 RBI to go along with 21 stolen bases. The Blue Jays won their first AL East title that year, and Bell hit .321 with three doubles in the ALCS vs. the Royals as Toronto fell in seven games.

“There’s not much room for progress,” Blue Jays hitting coach Cito Gaston told the Star about Bell in 1985. “He’s really proven himself.”

The Blue Jays could not repeat their division crown in 1986 as Jimy Williams replaced Bobby Cox – who returned to Atlanta – as manager. But Bell continued his ascendant play, hitting .309 with 38 doubles, 31 homers, 101 runs scored and 108 RBI while earning his second straight Silver Slugger Award and finishing fourth in the AL MVP voting.

Bell asked for a 1987 salary of $1.35 million in arbitration and the Blue Jays countered with an offer of $1.125 million – but the two parties settled at $1.175 before the case went before the arbitrator. Bell quickly showed that would be a bargain, hitting .308 with 47 homers and 111 runs scored while leading the AL with 134 RBI and 369 total bases. He outdistanced Detroit’s Alan Trammell by 21 points in the AL MVP voting, receiving 16 first-place votes compared to 12 for Trammell.

The season, however, ended on a sour note when the Blue Jays – who led the AL East for most of the season – were caught at the wire by the Tigers, who swept a three-game series from Toronto to end the year to finish with a two-game cushion in the division.

Toronto lost its last seven games of the season – including all three by one-run margins against the Tigers – as Bell went a combined 3-for-27 (.111) in those contests.

“I’ve been in slumps before,” Bell told the Star before the season’s final game, a 1-0 Toronto loss where Bell had one of the Blue Jays’ six hits. “You got to be happy. You got to have fun.”

But the late-season swoon would leave many questioning whether the Blue Jays could recover in subsequent seasons.

Meanwhile, Bell agreed to a two-year contract worth a reported $4 million that would cover the 1988 and 1989 seasons. But almost immediately, controversy surfaced when the Blue Jays announced that Bell would become their designated hitter, with Moseby moving to left field and youngsters Sil Campusano and Rob Ducey getting a chance to play center. The team believed Bell consented to this arrangement upon signing his contract on Feb. 17, but Bell did not agree.

“He feels like DHing degrades him, that it diminishes him as a player,” Williams told the Kansas City Times. “He stands up for what he believes in, and you have to respect him for that.”

But Bell feuded with Williams for most of Spring Training, at one point tossing a broken bat into the stands during batting practice.

“We’ll see who lasts here longer,” Bell told the Kansas City Times, “him or me.”

Duly inspired, Bell began the year by becoming the first player in history with three home runs on Opening Day – all three coming off Royals ace Bret Saberhagen. Of his 156 games that year, 149 came in left field. But Bell’s offensive numbers suffered as he batted .269 with 24 homers and 97 RBI as the Blue Jays finished third in the AL East. And his relationship with the media – which was always frosty – grew more tense.

Then in 1989, the Blue Jays got off to a 12-24 start before Williams was dismissed. He was replaced by Gaston, a beloved clubhouse presence who rallied the team to a 77-49 record to win the AL East title. Bell hit .297 with 41 doubles, 18 homers and a team-best 104 RBI.

Bell finished fourth in the AL MVP voting, his fourth Top 10 finish.

“He may be the best competitor I’ve ever been around,” Barfield told the Kansas City Times. “So when things don’t go his way, he will show it. What’s so bad about that? He may get ticked off from time to time, but that’s not all bad, either.”

That same year, Bell’s brother, Juan Bell, debuted with the Orioles in the first season of a seven-year big league career. Another brother, Rolando, played two seasons in the Dodgers’ farm system in the 1980s.

In the 1989 ALCS vs. Oakland, Bell batted .200 but ignited a Toronto rally in Game 5 that nearly extended the series. With the Blue Jays trailing 4-1 in the game and 3-games-to-1 in the series, Bell homered to lead of the bottom of the ninth, chasing Oakland ace Dave Stewart. Toronto then scored another run off Dennis Eckersley but could not push the tying tally across as the Athletics won 4-3 to advance to the World Series.

Bell, who spent most of 1989 in left field, DH’d for the final three games of the ALCS and spent more time as a designated hitter in 1990 – a year where the Blue Jays picked up the option on his contract worth another $2 million.

Bell hit .265 with 21 homers and 86 RBI that year, playing 36 of his 142 games as a DH. He was also named to his second All-Star Game that year, giving him even more national exposure as he headed into free agency following the season.

On Dec. 6, 1990, Bell signed a three-year deal with the Cubs worth $9.8 million, a contract that also included an option year for 1994.

“I’ve heard a lot of negatives about (Bell),” Cubs manager Don Zimmer told United Press International, mostly referring to Bell’s struggles in left field and with playing day baseball, a necessity at Wrigley Field. “But I went to some baseball people and they say if you leave George Bell alone, he’ll play his butt off.”

Bell hit .285 with 25 homers and 86 RBI in 1991. He was traded to the White Sox on March 30, 1992 – a deal that brought Ken Patterson and a young outfielder named Sammy Sosa to the Cubs.

“What we’re giving up is an outstanding hitter,” Cubs general manager Larry Himes told the Associated Press. “George will always be a good hitter.”

Sosa, however, would one day become a record-setting powerhouse.

Bell’s average dropped to .255 in 1992 but he hit 25 home runs and tallied 112 RBI. But in 1993, chronic knee pain limited him to 102 games – his first season since 1983 where he did not play in at least 142 contests. He finished the year with a .217 batting average, 13 homers and 64 RBI as Chicago won the AL West and advanced to the ALCS vs. the Blue Jays.

White Sox manager Gene Lamont opted not to put Bell in his starting lineup in the postseason – and Bell lashed out in the press.

“I don’t respect Gene Lamont as a manager or a man,” Bell told the Journal News of White Plains, N.Y. “What he’s doing is cruel. He’s not showing me any respect.”

The White Sox lost the series in six games, and Bell did not appear in any of them. With his contract expiring, Bell became a free agent when Chicago did not pick up his option. He soon retired.

In 12 big league seasons, Bell hit .278 with 308 doubles, 265 home runs and 1,002 RBI. He became the first Dominican player to win an AL or NL Most Valuable Player Award, with Sosa becoming the second in 1998 for the Cubs.

“It’s an easy life in the United States,” Bell told the Toronto Star in 1987. “Here in the Dominican, you have a lot of poor people. We know how to win. We don’t like to lose. I’m not tough because I like to fight but because I don’t like to lose.

“The Dominican people – they work hard.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum