The people I have most respected in my life were people who had courage… To this day whenever I see courage around me, in a man or a boy or a woman or a girl, in anybody, in a friend or even in someone I don’t particularly like, I am filled with respect and admiration.

Courage of Their Position

How do we sense courage? How do we know when we are in the presence of someone of transcendent character? How can we follow their lead?

A good place to start the search for the answers to those questions is the lobby of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The first thing guests see in the lobby are three magnificent bronze statues: Lou Gehrig, Jackie Robinson and Roberto Clemente. Dedicated in 2008, this set of icons, entitled “Character and Courage,” was sculpted by the late, great Stanley Bleifeld and donated by Jane and Robert Crotty.

“It was our way of giving back to a game that’s given us such joy,” said Crotty, now retired from his industrial cleaning business in Cincinnati. “Those players especially exemplify both the greatness and humility I’ve seen in so many baseball people. I often hear Hall of Famers say they want to go back to the Museum to make sure their plaques are still there. I feel the same way about the statues.”

The life-size figures don’t move, of course, but when you spend a little time with them, you can’t help but be moved. You can feel Gehrig’s resolve to play every game and hear his words, “…the luckiest man on the face of the earth” echo through the upper decks of Yankee Stadium. You can marvel at Robinson’s daring as he dashes down the third base line to steal home and change the course of the game. The years melt away as you remember one of Clemente’s throws to the plate, as strong and true as the man himself.

They start you on a journey through history that speaks to the very core of baseball, a trip that circles the bases and touches home not far from where you began, in the Hall of Fame’s sacred Plaque Gallery, where 346 honorees – players, managers, executives – are immortalized. Such is the nature of the game that they all possess a measure of the courage that Mantle found so inspiring.

One of them is Mike Schmidt, the great Phillies third baseman inducted into the Hall in 1995.

“How do you define courage?” the three-time NL MVP recently wrote. “It’s facing something that frightens you… It’s strength in the face of pain…It’s dealing with failures and bad breaks, it’s rehabbing injuries…It’s facing Bob Gibson or Nolan Ryan, but it’s also saying goodbye to your family before you leave on a two-week road trip.”

When you look at the plaques, you might wonder who the Hall of Famers looked up to, who were the heroes of these heroes.

Among the people that Mantle, with Bob Creamer, wrote about for “The Quality of Courage” were his father, Mutt, teammates Whitey Ford, Yogi Berra, Roger Maris and Billy Martin, and fellow icons Jackie Robinson, Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio. But he also paid tribute to Red Schoendienst for playing in the 1958 World Series while suffering from tuberculosis, and to Lou Brissie, who pitched for the Philadelphia A’s even after his leg was mangled by a bomb in the early days of World War II. The Mick also had a soft spot for players of small stature like Nellie Fox, Phil Rizzuto, Bobby Shantz and Albie Pearson.

Heroes come in all shapes and sizes and colors, and they don’t necessarily have to be Hall of Famers. Dennis Eckersley, inducted in 2004, said: “I wouldn’t be in the Hall of Fame without the loyalty and passion of my manager Tony La Russa, or the support and generosity of A’s owner Walter Haas, but if I were to pick one player who served as a guiding light, it would be Scott Sanderson. He passed away a few years ago of cancer, but for the nearly 20 years he pitched in the majors, he blessed all his teammates with his presence. We can only try to follow his example. Just a good, good man.”

Everywhere you turn as you walk through the Museum, you will find moments of courage, people to remember, injustices made right. A section of the second floor is devoted to the greatest drawing card of them all, Babe Ruth, but keeping him company are 19th century pioneers, black players denied the opportunity to play in the majors until Jackie Robinson came along, Latinos who both inspired Clemente and followed his lead, women who have made the game their own.

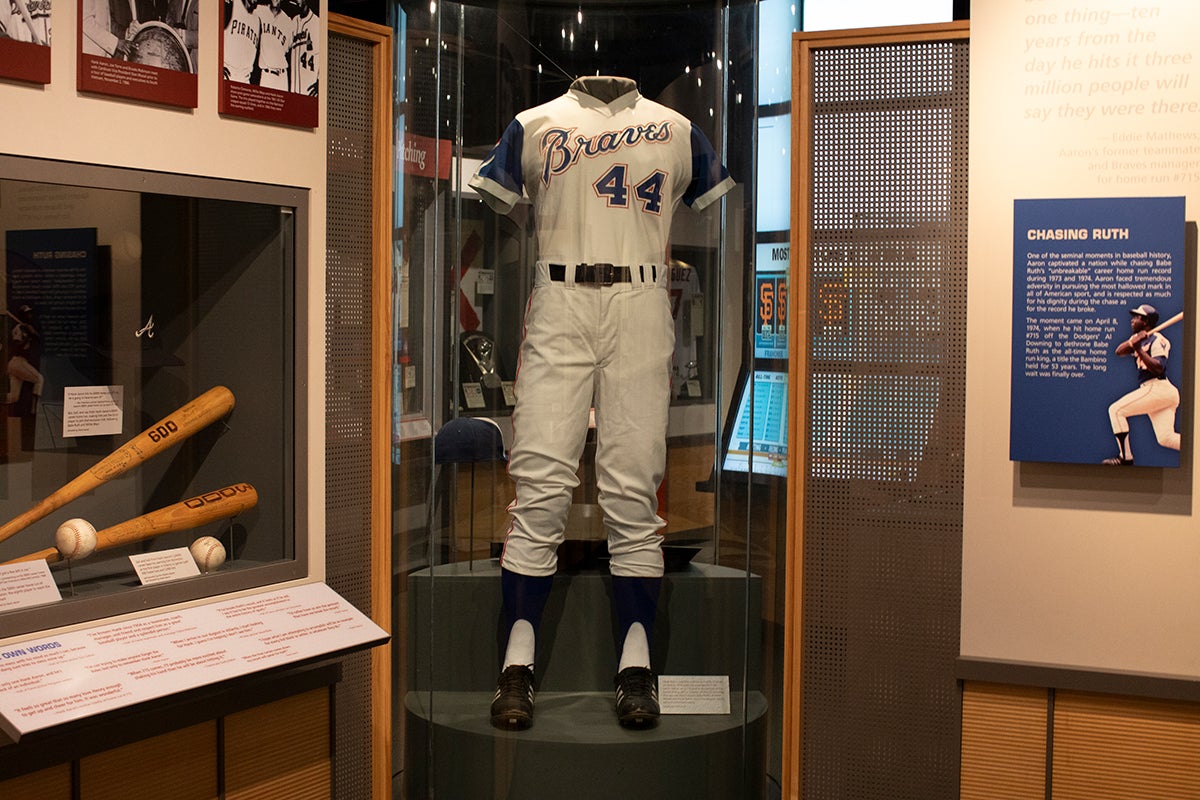

It makes a certain sense that Hank Aaron, who passed Ruth on the all-time home run list 50 years ago, is one floor above him in the Museum. In his exhibit, “Chasing The Dream,” visitors get a sense not only of his achievement, but also of the pressures on him—he was inundated with hate mail, for one thing.

“He was the best of us,” said Hall of Fame catcher Johnny Bench.

The third floor is also where you get to relive postseason glories like Don Larsen’s perfect game in the ’56 World Series, or Kirk Gibson’s walk-off homer off Eckersley in Game 1 of the ’88 Series between the Dodgers and A’s, or Jack Morris telling Twins manager Tom Kelly that he was going to finish Game 7 of the 1991 World Series, or Randy Johnson winning Game 7 of the 2001 Series for the Diamondbacks in relief after winning Game 6 the day before.

And then there’s the 20th anniversary celebration for the 2004 world championship that broke the Red Sox’ 86-year curse. If ever there was a team that exemplified courage, it was that one. Pick a hero: Dave Roberts stealing that base off Mariano Rivera to spark an impossible comeback against the Yankees in Game 4 of the ALCS; Tim Wakefield winning Game 5 in extra innings after sacrificing himself in Game 3 by saving the bullpen in a 19-8 blowout; Curt Schilling pitching with a bloodied sock to win Game 6 of that series; David Ortiz driving in the winning runs in both Games 4 and 5. And at the helm was Terry Francona, son of Tito Francona, who had played for Hall of Fame manager Al López, who had played for another manager in Cooperstown, Wilbert Robinson.

Leadership has a way of being passed from generation to generation. Pat Gillick, the Hall of Fame baseball executive, says: “If I had to pick a place where I got my start learning about the game, it would be 1962 in Elmira in the Orioles farm system. I was a pitcher on a staff with Dave McNally, Darold Knowles and Steve Dalkowski, and our manager was a guy named Earl Weaver. He was cantankerous even back then, but boy, did he know the game and the way to motivate his players.”

As it happens, Weaver’s mentor in the minors was George Kissell, a longtime protégé of Branch Rickey. That’s the same Branch Rickey who was managing the Cardinals when Lou Gehrig was a Yankee rookie in 1923, who had the courage to sign Jackie Robinson for the Brooklyn Dodgers with the intention of integrating baseball in 1947, who plucked Clemente from the Dodgers’ farm system when he was the general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1955.

Rickey’s in the Hall of Fame, of course, and his accomplice in signing Robinson and Clemente, scout Clyde Sukeforth, is also in the Museum. He’s hiding in plain sight in the Hall of Fame’s Art Gallery, in Norman Rockwell’s classic painting, “Game Called Because Of Rain” – Clyde is the man behind the umpires, Dodgers hat in hand, pointing to the sky.

“It’s funny,” says Jayson Stark of The Athletic, the 2019 winner of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America Career Excellence Award. “Baseball has all sorts of measurements nowadays – bat speed, launch angle, spin rate. But it still needs people who are judges of character.”

And it needs folks to pass the torch.

“That’s one of the things I love about the game,” says pitcher Bert Blyleven, inducted in 2011. “Taking the baton from someone you respect, and handing it to someone else. Jim Kaat, my fellow Dutchman, was one of my biggest influences when I got to the Twins, as was Jim Perry. So I made sure to pass what I learned onto Frank Viola – don’t pout when the second baseman makes an error behind you. I still get a kick out of working with the kids in Spring Training, though I’m not sure they listen to me as intently as I did to Warren Spahn.”

Kaat himself took his cues from the late Harmon Killebrew: “Harm was the strong, silent type. He was like the Lou Gehrig of his time. But I also admired guys who weren’t afraid to make a fuss. Curt Flood, for example. He paid a price for bucking the system, but because of him, players won the right to become free agents.”

“Where do I start?” says shortstop Barry Larkin, who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2012. “With my parents, of course. They gave me the foundation. I have to thank Pete Rose, Frank Robinson, Joe Morgan, Aaron and Mays, Robin Yount, Cal Ripken, Ozzie Smith for the examples they set… I walk into that building, and I am truly humbled.”

On April 25, 1976, in the fourth inning of a game at Dodger Stadium, Cubs center fielder Rick Monday spotted a man and his son in left dousing an American flag in lighter fluid in an attempt to set fire to it. Monday, who had served six years in the Marine Corps Reserves, rushed to the flag and snatched it away from them, running all the way to the third base line, where he handed it to Dodgers pitcher Doug Rau.

Monday was given a standing ovation and immortalized in stories and photos of the event. What he did that day reminded baseball fans of the hundreds of other players who left their posts to protect the country. Schmidt, whose father served in World War II, has a particular affection for those players.

“Bob Feller, Ted Williams and Willie Mays, to name a few, left the game to join the service in the middle of their careers,” Schmidt said. “For all those that made this decision, I salute your courage.”

Counting Morgan Bulkeley, who served in the Civil War, there are 72 Hall of Famers who interrupted their careers to serve their country. So think of all the other ballplayers who made that sacrifice. Cal Ripken played with one of them – Orioles center fielder Al Bumbry, who commanded a tank battalion in Vietnam and won a Bronze Star.

“Al didn’t talk at length about his time in Vietnam,” says Cal, "but his military service was evident in the way he carried himself. My dad loved the way Al played and the way he prepared. I remember stopping by the clubhouse after one of my high school games, and Al yelled, ‘Rip, Junior must have had a good game—look how dirty his uniform is!’ He was that kind of guy, always lifting people up and enjoying everyone around him.

Mantle also highlights a World War II veteran in his book: Lou Brissie, who pitched for the Philadelphia A’s even after his leg was mangled by a bomb that went off while he was leading a squad in the hills of Italy. He talked doctors into reconstructing his leg and Connie Mack into giving him a chance. His first major league victory came in 1946 when he struck out Ted Williams, and he would go on to win 44 more.

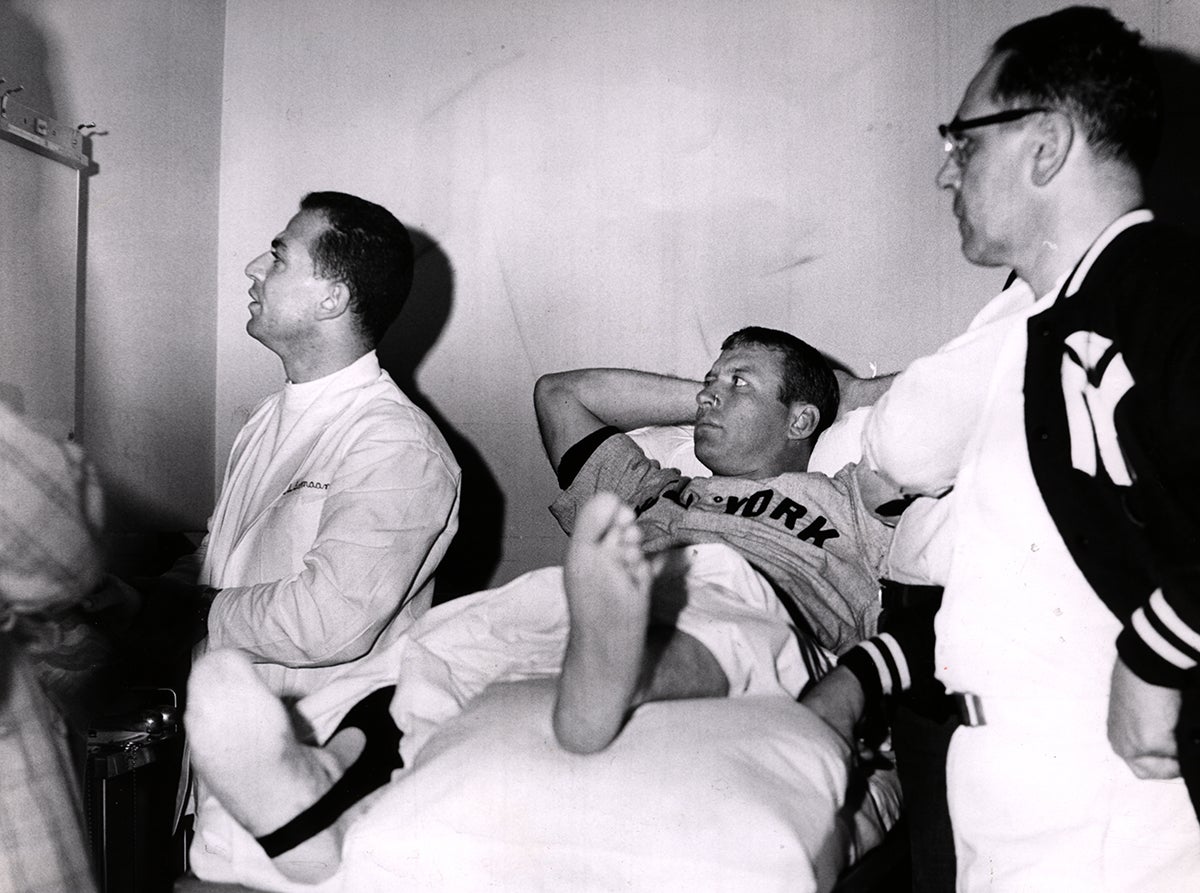

When The Quality of Courage came out, Mantle was still in his prime – he would finish second in the MVP voting in ’64. He was renowned not only for his otherworldly talents, but also for his tolerance to pain. In his introduction to the book, Creamer describes his heroism in Game 4 of the 1961 World Series, when he played with a badly infected hip. In the fourth inning, after running hard to beat out a single that turned out to be the winning run, Mantle was taken out of the game by manager Ralph Houk because blood was seeping through his uniform.

Said Houk: “He went into the clubhouse and they put another dressing on it, and after a while he came back and sat on the bench and rooted the rest of the game. Mickey was something else.”

He did something else later in life that helped change lives. He publicly admitted his addiction to alcohol in a 1994 Sports Illustrated article that served as a wakeup call to others who were abusing alcohol and drugs. That took courage, the same kind of fortitude that Waite Hoyt, the Hall of Fame pitcher and Reds broadcaster, showed when he became a spokesman for Alcoholics Anonymous, the same willingness to come clean that helped Dennis Eckersley find the strike zone and become the best reliever in baseball.

“People often thank me for inspiring them,” said Eckersley, “and I thank them in return.”

Here’s another definition of courage: Four years after giving up the walk-off to Kirk Gibson, Eckersley saved a record 51 games and won both the AL Cy Young and MVP awards.

There’s a new statue on the first floor of the Hall, at the base of the Grand Staircase.

Dedicated on May 23, 2024, it’s a bronze of Henry Aaron, who broke Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record 50 years ago. Sculpted by Will Behrends, it too was donated by the Crotty family. And it comes with a little story of courage attached.

“It’s Opening Day, April 4, of the 1974 season,” recalls Bob Crotty, “and me and four of my friends are sitting behind our desks at Kettering (Ohio) Junior High School. The Braves are playing the Reds, with Hank Aaron sitting on 713 homers, one behind Ruth. At around 10:30 a.m., I shout, ‘Let’s go!’, and the five of us take off down the hall with teachers screaming at us from behind. We ran toward the highway, stuck out our thumbs, and sure enough, we were in a car heading toward Cincinnati, 50 miles away. We arrive at Riverfront Stadium right before gametime, and run into some teachers who had extra tickets – they were skipping school themselves. Suddenly, we hear a roar from the crowd, and just as we get to the concourse, we see No. 44 rounding third and heading home after hitting a three-run homer off Jack Billingham.

Just before he’s mobbed at home plate, the Reds’ catcher shakes his hand. Guy named Johnny Bench.

“So when I went back for this year’s Induction Ceremony, I asked Johnny to pose with the statue of Aaron.”

“Henry was my hero,” Bench said. “In my very first game with the Reds against the Braves, 1967, he took that distinctive stance of his, adjusted the helmet on his hat and said, ‘Hi, John.’ He must’ve heard about me, or something, but anyway, we maintained our friendship until he passed away a few years ago. I well remember No. 713. It’s the catcher’s job to block the plate, so I made sure to reach out and shake his hand before he was swept away.

“I think I saw the statue crack a smile when I went up to (the statue).”

Steve Wulf has written about baseball for Sports Illustrated, Time, Life and ESPN. His own hero is Robert Creamer, the acclaimed author of "Babe" and the man who assigned him his first story for SI almost 50 years ago.