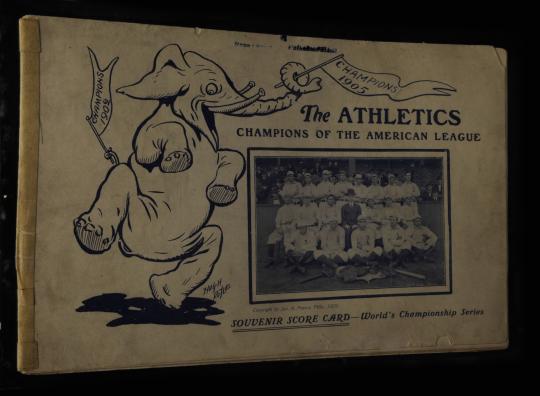

"The A’s defiantly adopted the white elephant both as a symbol of pride and an opportunity to refute and ridicule McGraw."

The Elephant in the Room

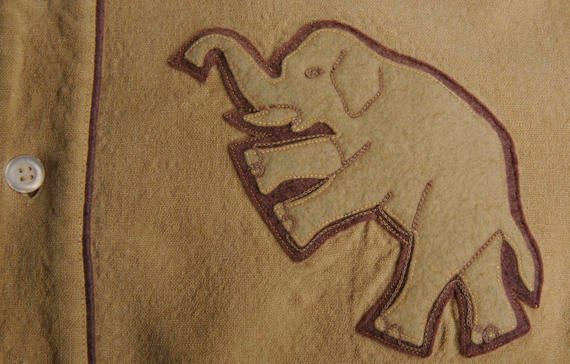

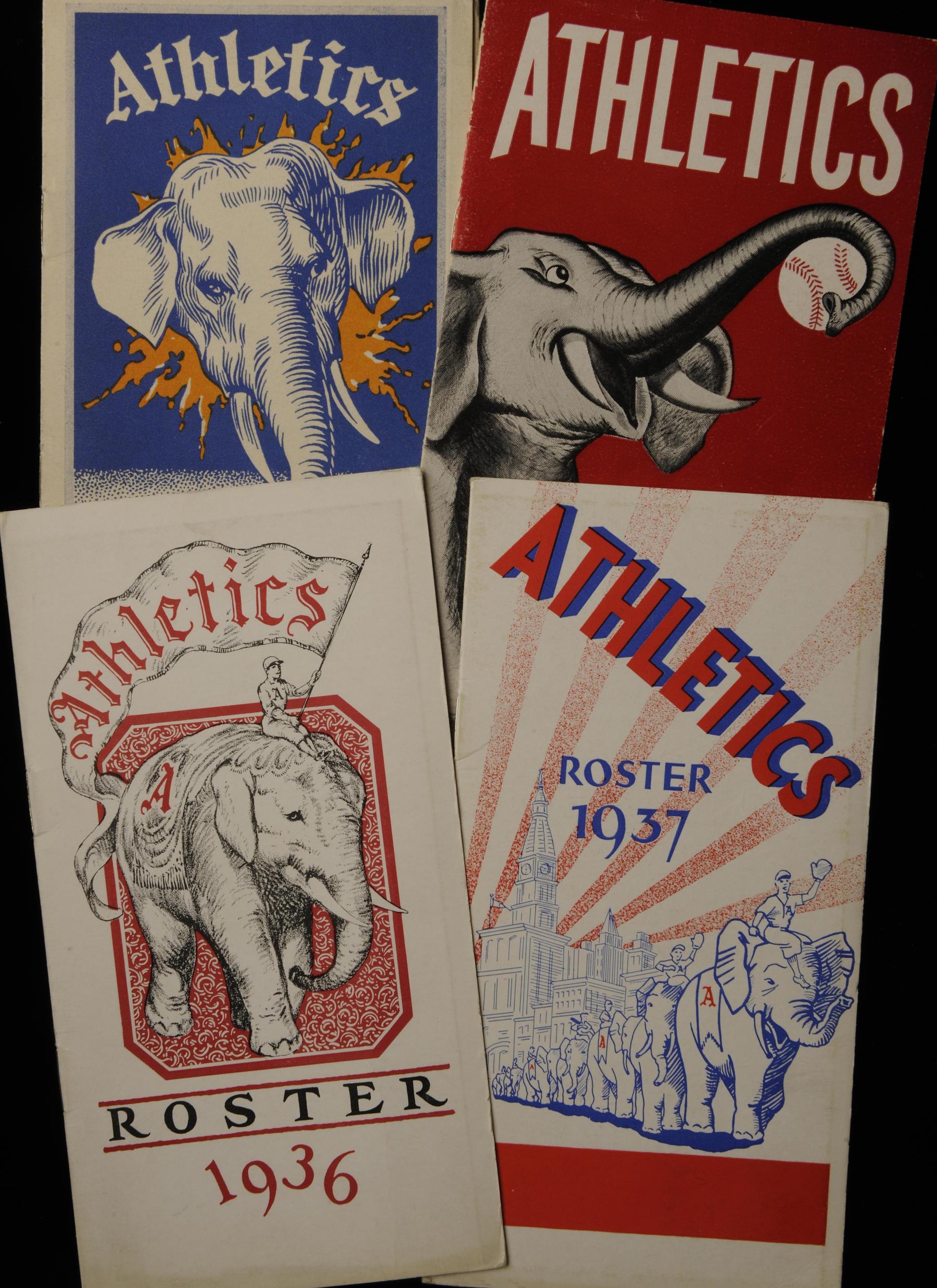

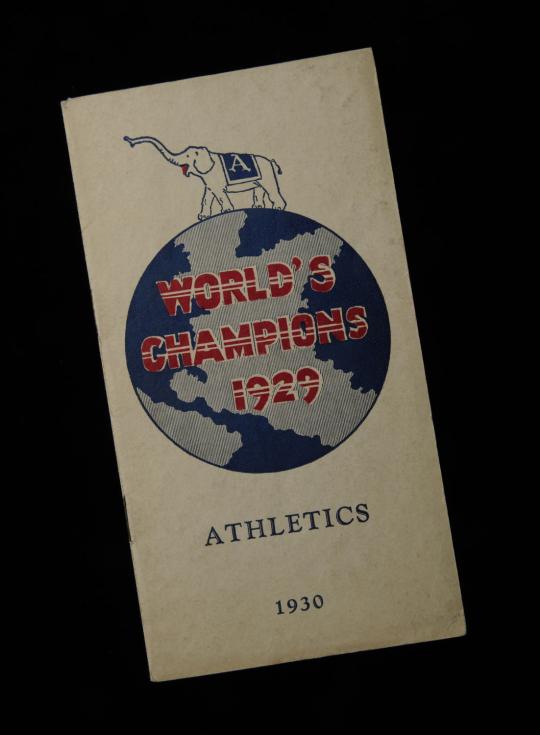

The elephant retreated from the jersey in 1928 as the “A” returned. Although the animal would not return to the jersey during the rest of the franchise’s duration in Philadelphia, it remained a potent symbol for the A’s. In a variety of guises, the pachyderm appeared on World Series press pins, team letterhead, and extensively in publications. In contrast to today’s rigorous trademark practices, the Athletics used a variety of elephants on their publications, some more realistic, others more fanciful. Compared to the stolid elephant of the 1920s, the 1940s and 50s versions were more animated, often seeming to smile and frequently swinging a bat in its trunk. But by the franchise’s fifth decade, he elephant might have been lively, but the franchise was not – trailing the league in both standings and attendance.

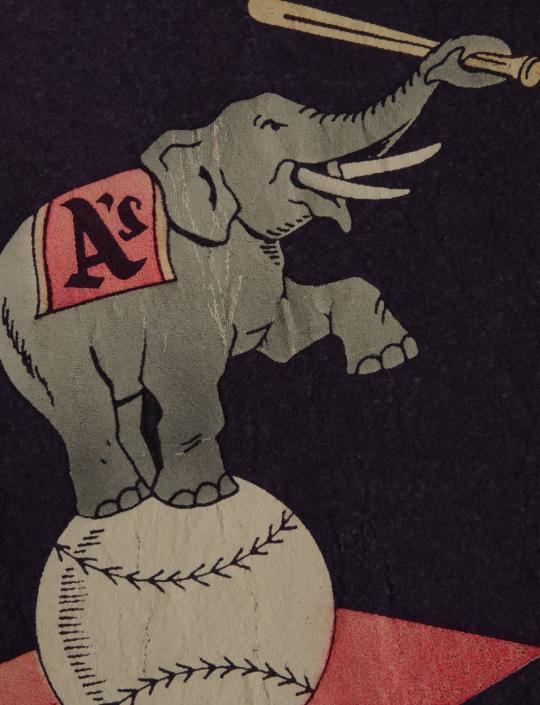

In 1955, businessman Arnold Johnson bought the club and moved it to Kansas City. He reintroduced the elephant, now blue (again) and perched on a baseball, onto the jersey sleeve, much as Philadelphia had in 1918. The elephant was short-lived in Kansas City, however. When Johnson died suddenly in 1960, Charles O. Finley purchased the franchise and immediately revamped its image, beginning by banishing the elephant and later replacing it with the Missouri mule. The new mascot, named (appropriately enough) Charlie O., was not embraced by the fans, who saw it as an insincere use of the state animal. When Finley left for Oakland in 1967, he brought with him the mule, the new green and gold uniforms, and the Athletics nickname, but continued to refuse to re-employ the elephant.

The elephant’s renaissance began in 1988, under the regime of owner Walter A. Haas Jr., who had purchased the A’s from Finley in 1981. Haas returned the elephant on a ball logo, now green and gold rather than blue or white, to its “proper” place on the left sleeve. From 1988 to 1990, the reintroduced elephant was immediately rewarded with three American League pennants and the 1989 World Championship. At about this same time the Athletics also brought forth the elephant as a living, breathing mascot that walked around the stadium. First as Harry Elephante, now as Stomper, the pachyderm became increasingly linked with the franchise.