Felipe Alou challenged racism en route to the big leagues

Nine years after Jackie Robinson courageously reintegrated baseball, Felipe Alou was kicked off his first minor league team because he was dark-skinned.

As someone who knew of racism while growing up in his native Dominican Republic but had never experienced it, it was understandably unsettling for Alou – especially so for a 20-year-old who didn’t know English and was new to the United States.

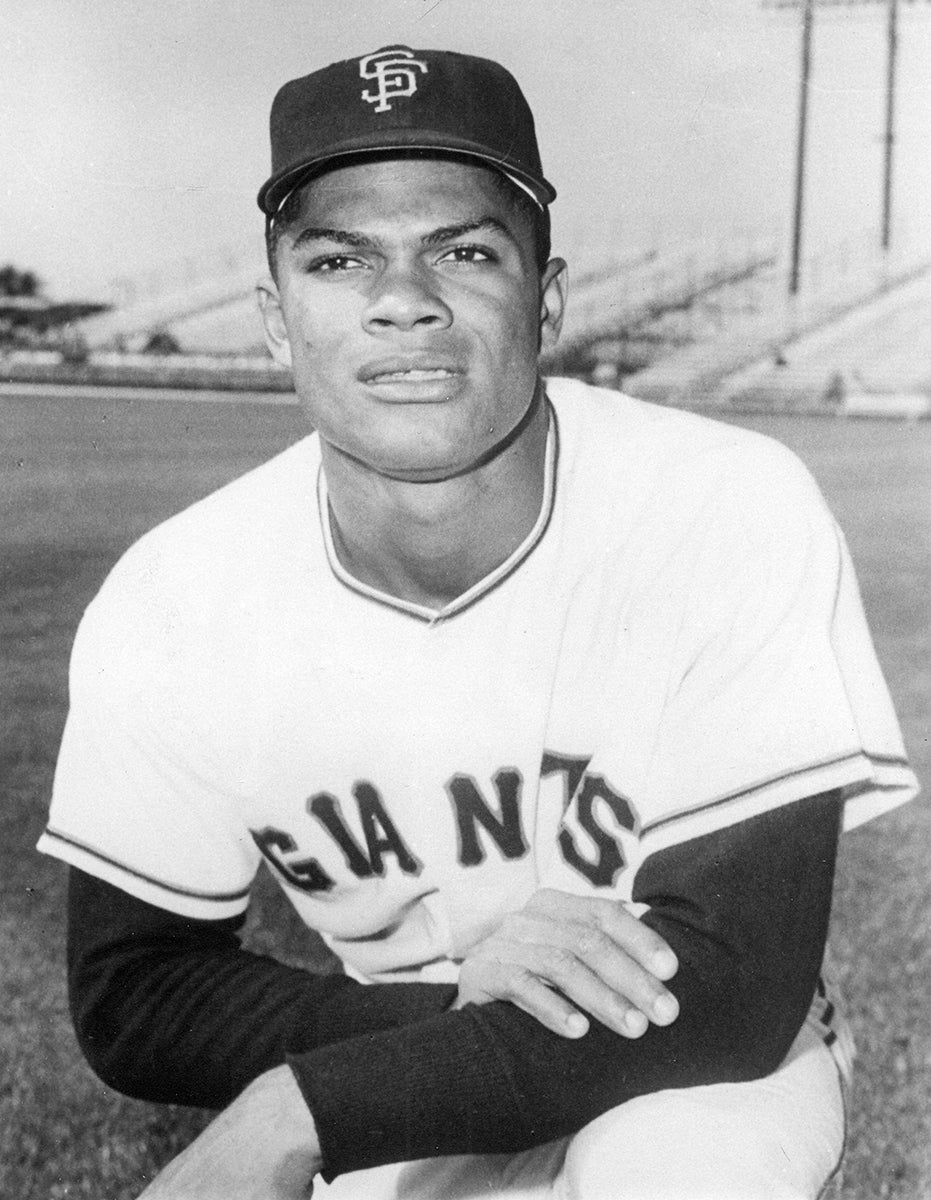

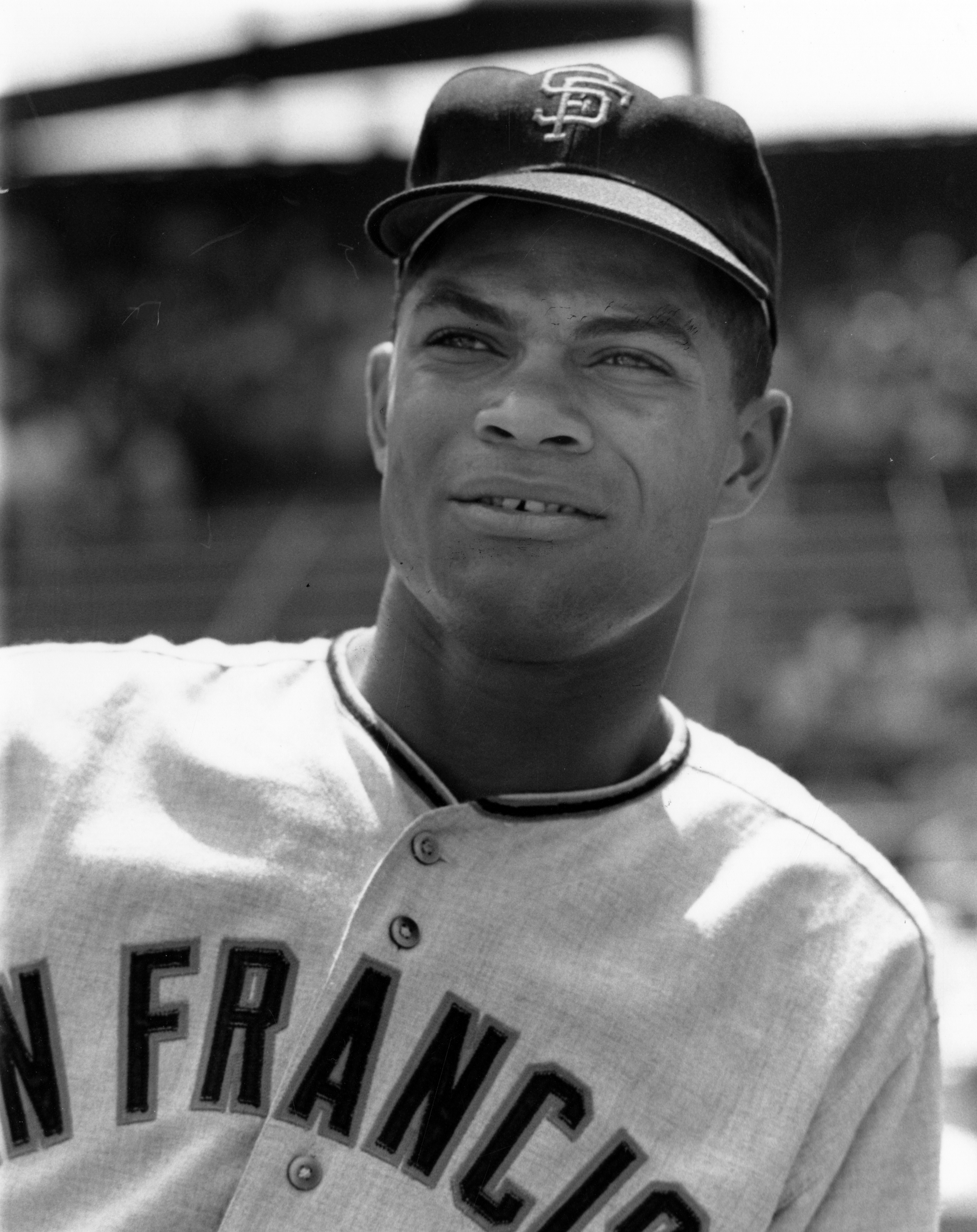

Alou, who would go on to long and successful playing and managerial careers in the major leagues, is but one example of Afro-Latinos who overcame segregation on their baseball journey.

Alou, now 88, grew up in Bajos de Haina – about seven miles from Santo Domingo – along with his younger brothers, Jesús and Matty, with whom he formed the only “all-brother” outfield in Major League history with the San Francisco Giants in 1963. Felipe began his professional baseball career, after signing with the New York Giants as an amateur free agent on November 14, 1955, with the Lake Charles (La.) Giants in the Class C Evangeline League. Little did he suspect what was in store for him early in that inaugural campaign.

In 1956, the Evangeline League was made up of eight Louisiana-based teams: Alexandria, Baton Rouge, Crowley, Lafayette, Lake Charles, Monroe, New Iberia and Thibodaux. Alou initially arrived late in Sanford, Fla., the minor league training base of the Giants, due to a delay in getting his passport. Eventually, a place was found for him with the Lake Charles club.

Unfortunately, for Alou and others, on April 4, 13 days before the Evangeline League season opened, the Baton Rouge recreation commission disclosed that Black players be banned from Pete Goldsby Memorial Field, the home ballpark of the Baton Rouge Rebels. The ruling had been adopted Jan. 17.

In making the announcement, Norman David, vice chairman of the commission, said: “We want it known in advance so that no team will have a key Negro player and be hamstrung when he can’t play here.” Lake Charles and Lafayette were the only clubs in the league with Black players. In 1955, home games were held in private parks around the league, but in ’56 Baton Rouge returned to its public park.

It was also announced that if a visiting team uses a Negro player at Baton Rouge, the Rebels will have to forfeit that game, as it is the obligation of the home club to furnish the site.

Lake Charles’ roster included a trio of Black players, including Alou, shortstop Ralph Crosby and outfielder Chuck Weatherspoon. When the Giants first visited Baton Rouge on April 27, a “gentleman’s agreement” was worked out where if the visitors benched Alou and Crosby (Weatherspoon was injured), the Rebels would play without their white players from the same positions – shortstop Ken Adkins and outfielder Bob Meador. Lake Charles manager Mike McCormick, a former big-league outfielder in the 1940s, said it was a compromise he made to get the game in.

The next night, however, the listing of Crosby in the Lake Charles Giants’ lineup caused a postponement. Baton Rouge expected Lake Charles to list at least one Black ballplayer in the starting lineup and didn’t open their ticket office. Before the Saturday game, McCormick announced: “My entire ballclub will be dressed out tonight” with Crosby at shortstop and Alou “on the active list.”

Umpire Joe Powers gave the lineup card to Bob Breazeale, president of Baseball Fans, Inc., which operated the Baton Rouge team. The public address system then read a statement to the approximately 600 fans on hand, explaining that the game had to be postponed because of the segregation ban.

Breazeale’s response: “If that’s what he does, then we’ll have to issue a statement when it’s time for the game to start that we can’t play because of the park commission policy against it. We will announce that the game has been postponed.”

The Lafayette Oilers, who fielded the league’s two other Black players – Sam Drake and Manuel Trabous – were scheduled to visit Baton Rouge the following week. Their president, Harry Romero, announced his plan was to play his Black players in those contests, adding he had no choice in the matter since the Chicago Cubs, of which the Oilers were a minor league affiliate, notified him they “would not be responsible for where Lafayette finished in the standings,” nor would they promise to make any commitment about the 1957 season. Instead, Baton Rouge canceled the game with Lafayette.

One team director said Baton Rouge had three choices: forfeit all home games, play all such games on the road, or drop out of the league.

The Evangeline League’s segregation problem was solved by announcement on May 6, 1956, that all five Black players in the Class C circuit were being transferred. The order came following a meeting the previous night of league officials with league president Roy “Moon” Mullins. After only five game and nine at-bats with Lake Charles, Alou was optioned to the Cocoa (Fla.) Indians of the Class D Florida State League.

Mullins said segregation had nothing to do with the Black player movement, adding the two Lafayette players had received promotions while Lake Charles dropped its three players because they weren’t good enough.

“We were very fortunate to have this problem work out in the way it did,” Mullins said. “If a boy is good enough to make the ballclub, regardless of his race, there is nothing the league can do about it. It just happened that the Negroes on the Lafayette and Lake Charles clubs were either needed elsewhere or not good enough to make the team this year. What will be worked out in any future situation cannot be foretold – we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.”

Exposing Mullins’ incredulous statement was Jack Schwarz, the assistant minor league farm director of the New York Giants, who reported the three Black players had to be moved by the Lake Charles ballclub because the Evangeline League found them “undesirable.”

“We have a working agreement with Lake Charles,” Schwarz said. “Under that agreement, the team can return players to us whenever they so desire.

“That was done in this case. Lake Charles told us it had to get rid of the three players and they were tossed to us. We all felt badly about it. They were good players and popular with the fans there. But it threatened to break up the league.”

According to Schwarz, he was told that the league has a rule which permitted the ousting of any member found “undesirable” by a majority vote of the directors.

“Lake Charles played one game with a Negro player and the game was ordered forfeited,” Schwarz said. “Later this action was rescinded. Then the league held a meeting and told Lake Charles and Lafayette to get rid of their Negro players or face expulsion unless this action was taken. So we couldn’t do anything but take back the players.”

Coincidently or not, on May 12, 1956, Jackie Robinson penned a piece for the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the country’s most highly circulated Black newspapers at the time, about the South and baseball.

“When I first broke into organized baseball back in 1946 I was exposed to the worst type of discrimination. I didn’t like it then and certainly I don’t like it now,” Robinson wrote. “Everywhere baseball is played there have been improvements. I’ll grant that. However, after 10 years of travelling in the South, I don’t think the advances made there have been fast enough.

“To a large extent the Southerners, particularly those in politics, are to blame. On the other hand, it’s my belief that baseball itself hasn’t done all it can to help remedy the problems faced by those playing in organized baseball. Baseball, as everyone knows, is big business. Every year millions of dollars are spent in the South directly or indirectly because of baseball. It is my belief therefore that pressures can be brought to bear by heads of organized baseball that would help remedy a lot of the prejudices that surround the game as it’s played below the Mason-Dixon Line.

“I know there are those who will say that the fight for equality isn’t baseball’s to solve. But I remember when there were people who said when Branch Rickey first signed me that I wouldn’t be accepted in the majors. I, and those who have followed me, are living examples of how farfetched those statements were. That is why I believe that baseball, as an organization, can help combat a lot of injustices.”

The Louisiana Weekly, a Black newspaper published in New Orleans, expressed similar outrage to its readers.

“Jim Crow, the unwanted and anti-democratic pitcher, tossed some wicked curves from the mound and struck out five Negro players in the Evangeline League Saturday night, when it was revealed that the tan players in the Class C baseball loop were being transferred,” it read. “Shortly after the announcement … reports from Lake Charles and Lafayette reveal that Negro baseball fans started setting their wheels in motion to boycott the entire league. The general feeling … was that Negro fans would not support the clubs until Negro players again don the Oilers and Giants uniforms.

“Baseball fans are of the opinion if they can’t follow the integrated pattern of the big leagues and Triple-A leagues ‘they need to fold up.’ Real baseball fans want to see the best players at all times and not concerned with the color of a player’s skin.”

Another Black newspaper, the Atlanta Daily World, published sports columnist Marion E. Jackson’s scathing rebuke of the Evangeline League’s action on Sept. 19, 1956.

“The Evangeline League, which barred Negro players last spring, cancelled the final rounds of its playoffs due to lack of interest,” Jackson wrote. “The Class C circuit ignored a grim warning that every loop that has bowed to race prejudice has been washed away by public opinion.

“It is amazing how these Nullicrats whitewash wrong to make it look right. The Evangeline League was a thriving, red-corpuscled loop a few months ago when bronze players were making the turnstiles click. Then the segregationists seized control of mass opinion and ramrodded a series of segregation measures. As a result, the N.Y. Giants were forced to give up its Lake Charles club, other major league clubs broke agreements, and now the end is in sight.”

In 1956, Alou experienced for the first time what it was to be discriminated against because of the color of his skin. Six decades later, he reflected on his tumultuous beginning in organized baseball in his 2018 autobiography, “Alou: My Baseball Journey” written with Peter Kerasotis.

“I knew racism existed, but nothing prepared me for this – certainly not my upbringing, being the son of a white woman of Spanish descent and a black father who was the grandson of slaves who were likely ripped away from Africa in the early 1800s to work Hispaniola farms,” Alou wrote. “Even the several days I spent in spring training in Melbourne, Florida, before the Giants shipped me to Louisiana, didn’t give me much of an inkling of what was in store. In Lake Charles, Louisiana, I learned firsthand about racism.

“Growing up in the Dominican Republic, we used to talk about how you had to be careful in America, so I knew, if only academically, about racism. But until now I had not seen the face of racism. I didn’t know I would have to sit in the back of the bus. I didn’t know I couldn’t look at a white girl. I didn’t know I couldn’t eat in the same restaurants as whites. I didn’t know I couldn’t stay in the same motels. I didn’t know I couldn’t drink from the same water fountains. I didn’t know I couldn’t use the same bathrooms. On a road trip in Baton Rouge, I couldn’t even enter the stadium through the players’ entrance, much less enter the clubhouse. I had to sit in the bleachers in what was called the colored section. All of it was startling to me. Until you confront a lion, you don’t know how ferocious he is.”

Though Alou’s time was short-lived with the Lake Charles ballclub in ’56, he was the only one who played with the team to eventually make it to the big leagues. And his time with Cocoa in the FSL that year resulted in him leading the circuit in batting average (.380), on-base percentage (.460), slugging percentage (.582) and stolen bases (48).

“Because I could hit right away as a professional player, I felt mostly accepted by my teammates,” Alou wrote. “And Cocoa turned out to be a paradise for me. The fishing, the weather, the vegetation, it reminded me of home.”

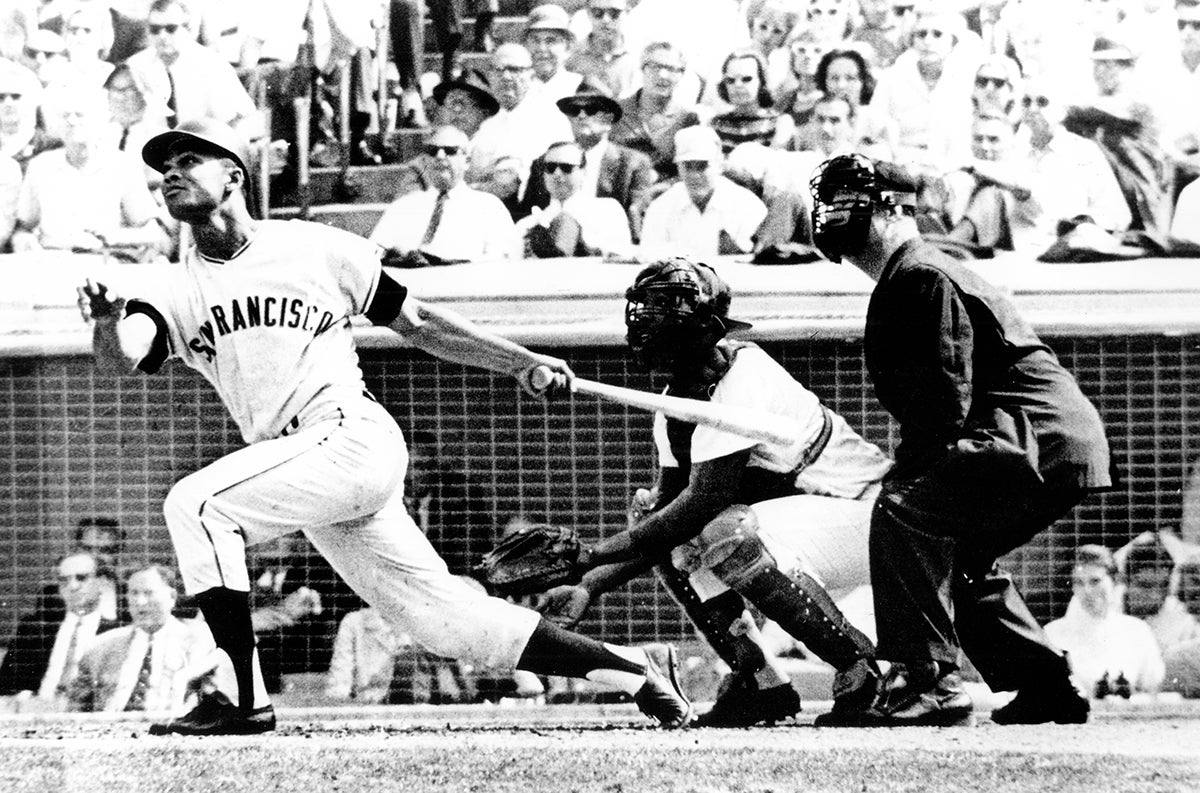

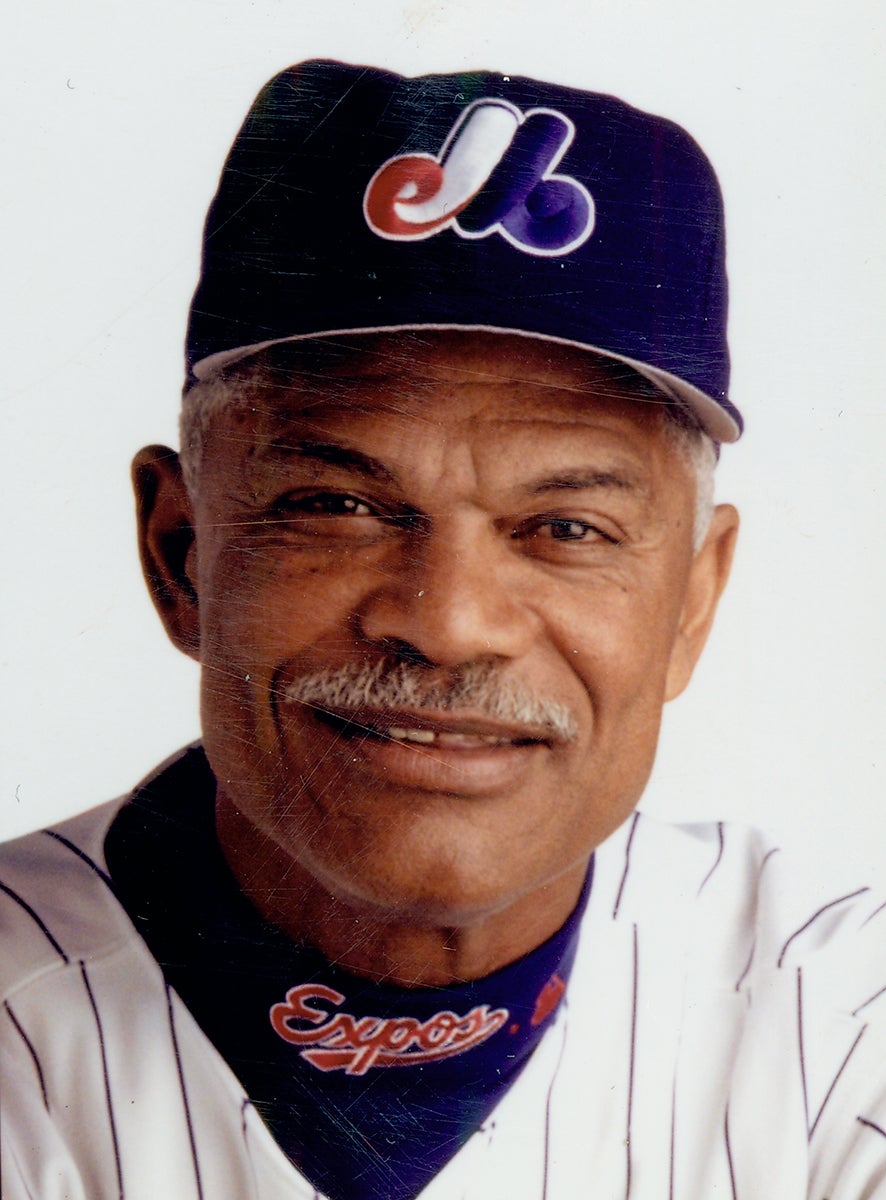

After making his major league debut with the Giants in 1958, Alou would enjoy a 17-season career that also included stops with the Braves, Yankees, A’s, Expos and Brewers. Finishing with 2,101 hits, 206 home runs and a .286 batting average, the three-time All-Star, who was the second Dominican major leaguer (Ozzie Virgil being the first with the Giants in 1956), became the first Dominican manager in major league history with the Expos in 1992. In 14 years as skipper with both the Expos and Giants, Alou finished with a 1,033-1,021 record, a 100-win season with the Giants in 2003, and a National League Manager of the Year Award in 1994.

Unlike Alou’s, the Evangeline League’s future wasn’t so bright. Having been in existence since 1934, except for a few seasons during World War II, it ceased operations following the ’57 campaign.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum