- Home

- Our Stories

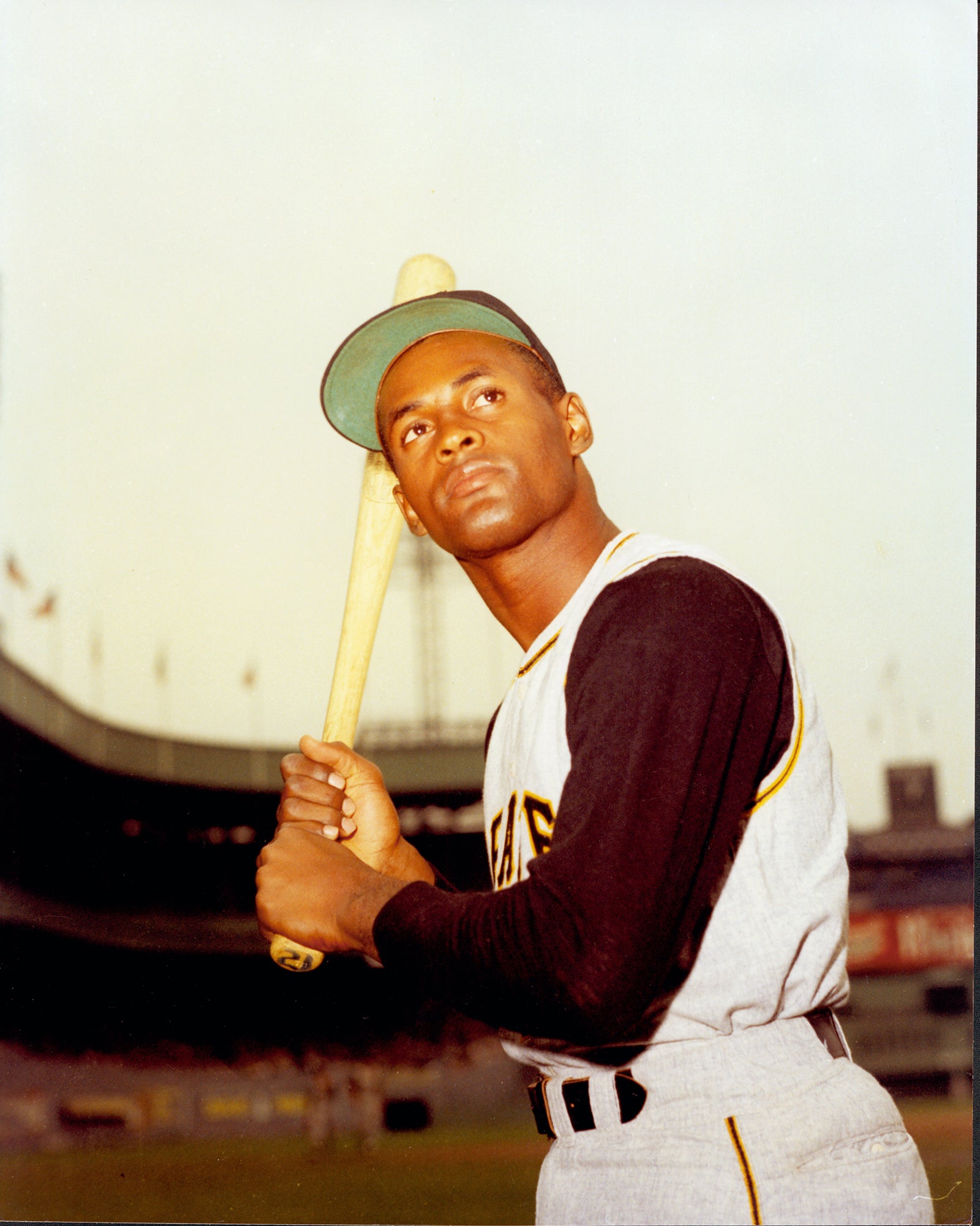

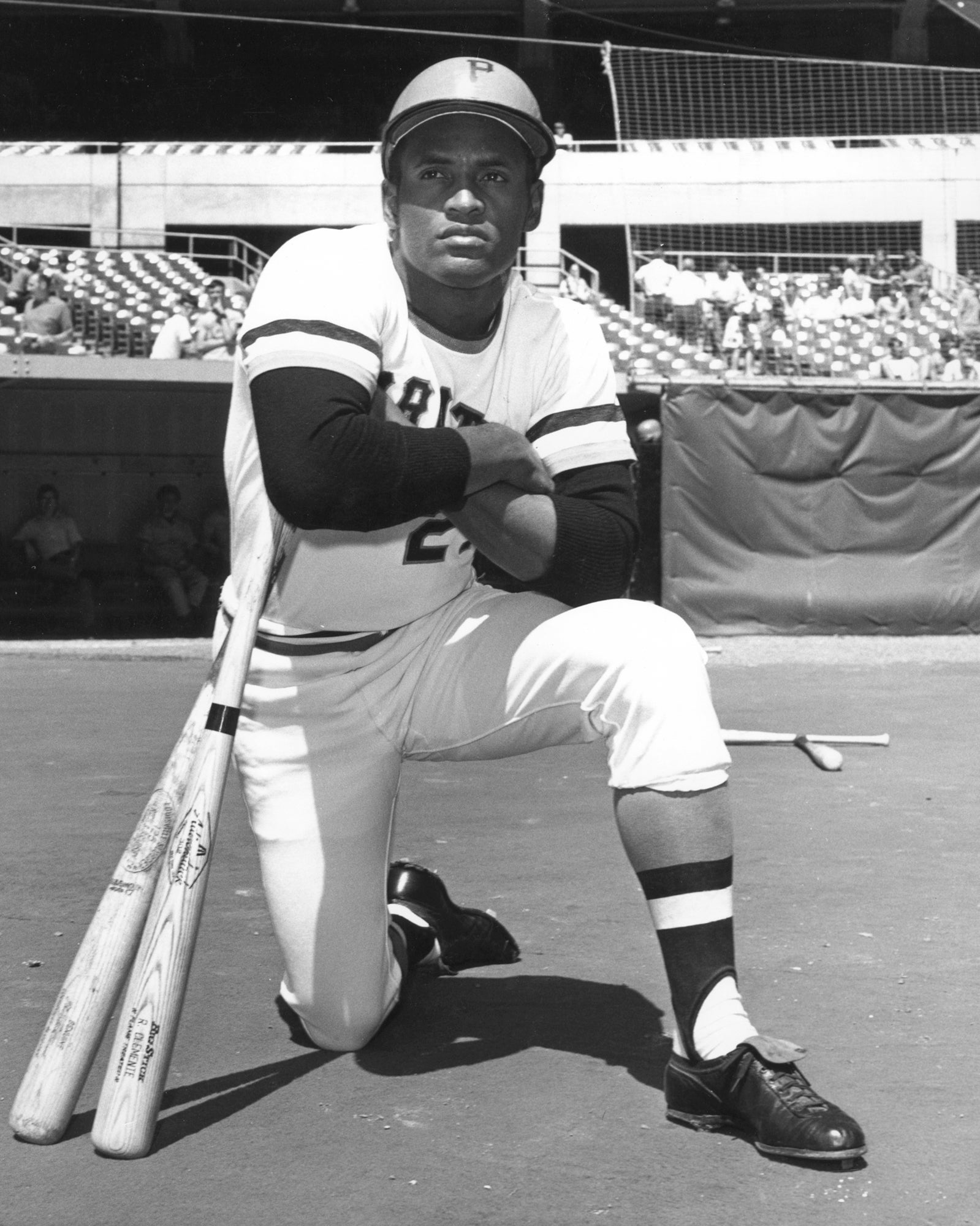

- #GoingDeep: Carlos Bernier left legacy as Latin American pioneer

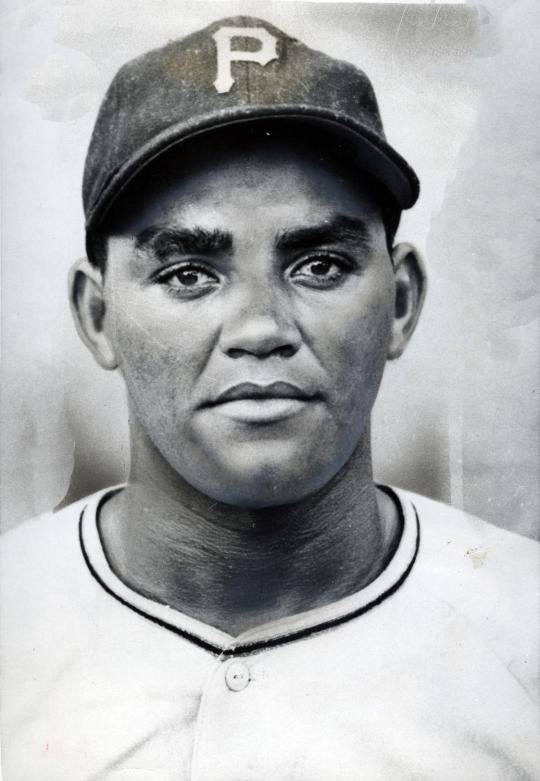

#GoingDeep: Carlos Bernier left legacy as Latin American pioneer

Carlos Bernier was arguably the fastest ballplayer around, his blinding speed making him a legend on the basepaths and a fly-chasing defensive star in the outfield.

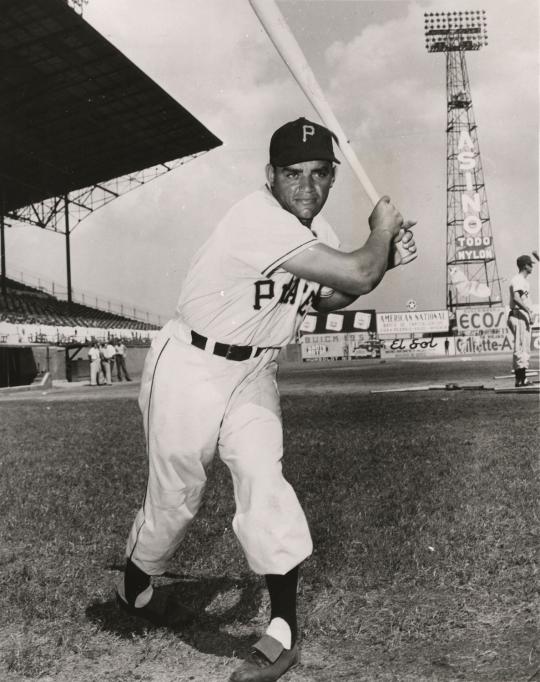

Seven decades ago, Bernier began the 1953 season as a flashy young rookie starting in center field for the Pittsburgh Pirates, flanked on each side by veterans Ralph Kiner and Frank Thomas. Despite getting off to a fast start for the Pirates, ultimately his inability to “steal first base” proved hard to overcome.

Even though he lasted only one big league season, he made an indelible mark in the sport during an 18-season professional diamond career.

Born in Puerto Rico in 1927, Bernier started playing baseball at 13, learning the game on the island’s sandlot fields. Puerto Rican-born players began appearing in the big leagues in 1942 with Hiram Bithorn, but only a little more than two dozen – most notably Luis Olmo – had played by the time Bernier appeared on the scene.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

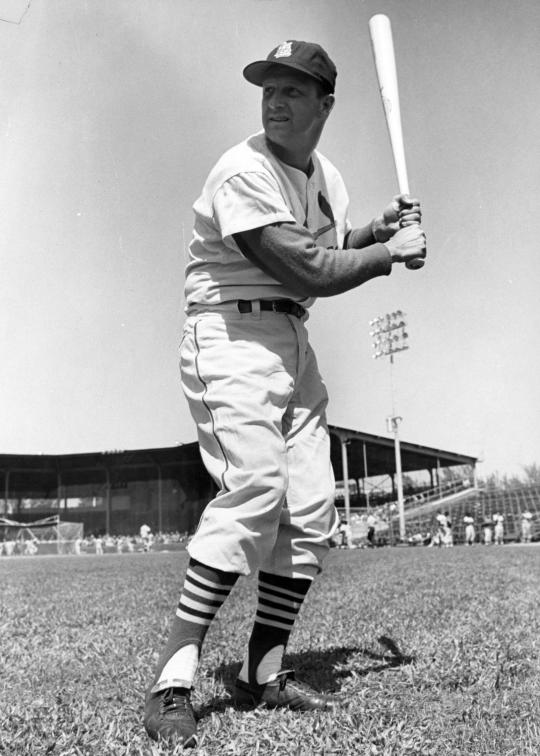

At 5-foot-9 and a stocky 180 pounds, the right-handed batter, a familiar wad of tobacco in his cheek, modeled his closed batting stance after Cardinals star Stan Musial, standing deep in the batter’s box, feet together and in a slight crouch.

First appearing in the minor leagues in 1948 at age 21, Bernier’s first five seasons were spent in two countries and across the United States: Port Chester, N.Y.; Bristol, Conn.; St. Jean, Quebec; Tampa, Fla.; and Hollywood, Calif.

Along the way, he topped the Colonial League with 89 stolen bases in 1949; swiped a total of 94 in two leagues, the Colonial and Provincial, in 1950; and led the Florida International League with 51 thefts in 1951 and the Pacific Coast League with 65 in 1952.

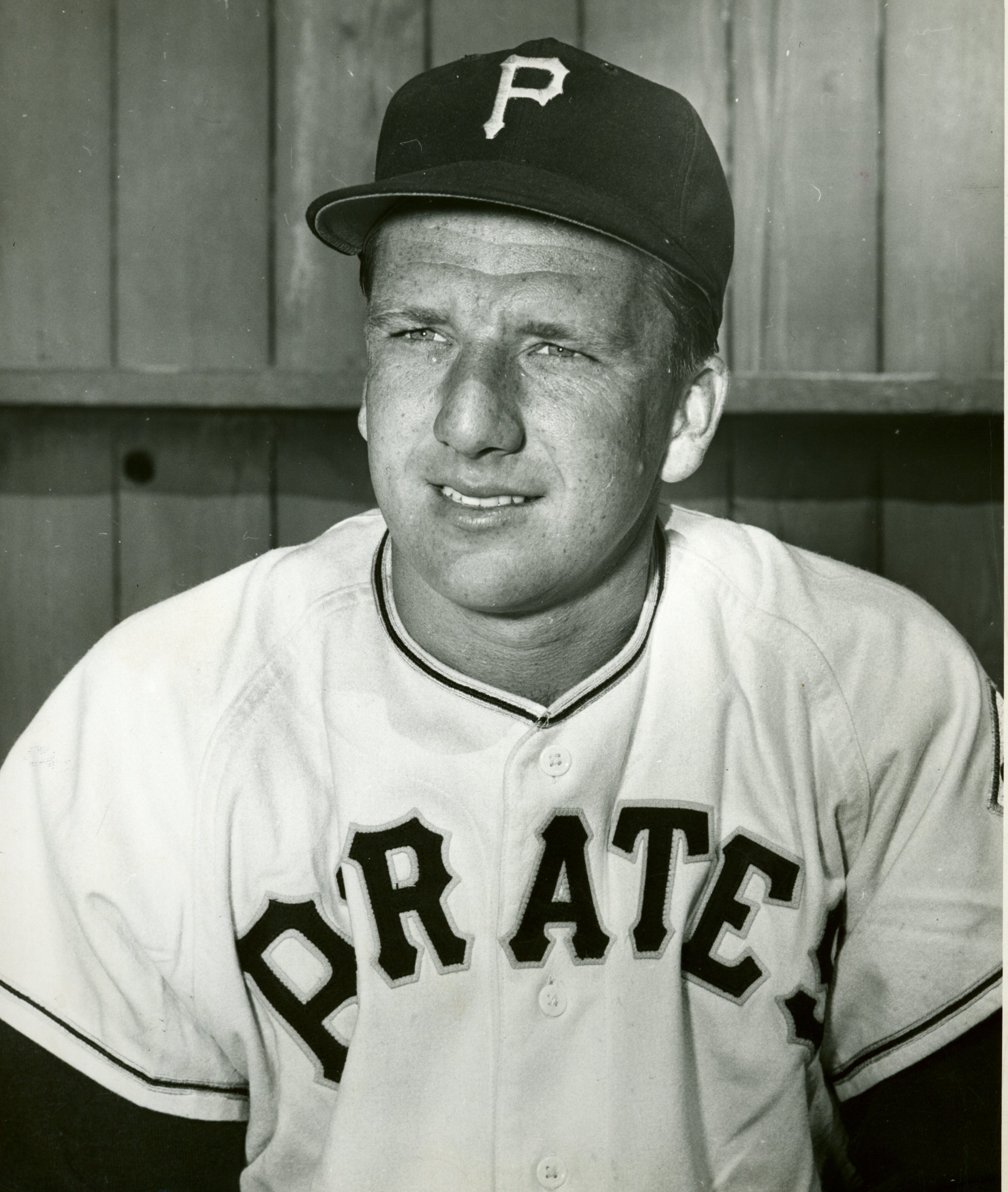

Fred Haney, Bernier’s manager with Hollywood in 1952, said: “The three parts of swiping a base are jump, speed and slide. Carlos is outstanding in all three, but it’s his jump that really turns the trick.”

Bernier also led his respective leagues in runs scored in 1949 (136), 1951 (124) and 1952 (105).

The press began referring to him, both for his fleetness as well as his renowned temper, as The Puerto Rican Rocket, the Bandit, the Hotheaded Latin, the Puerto Rican Pepperpot and the Comet.

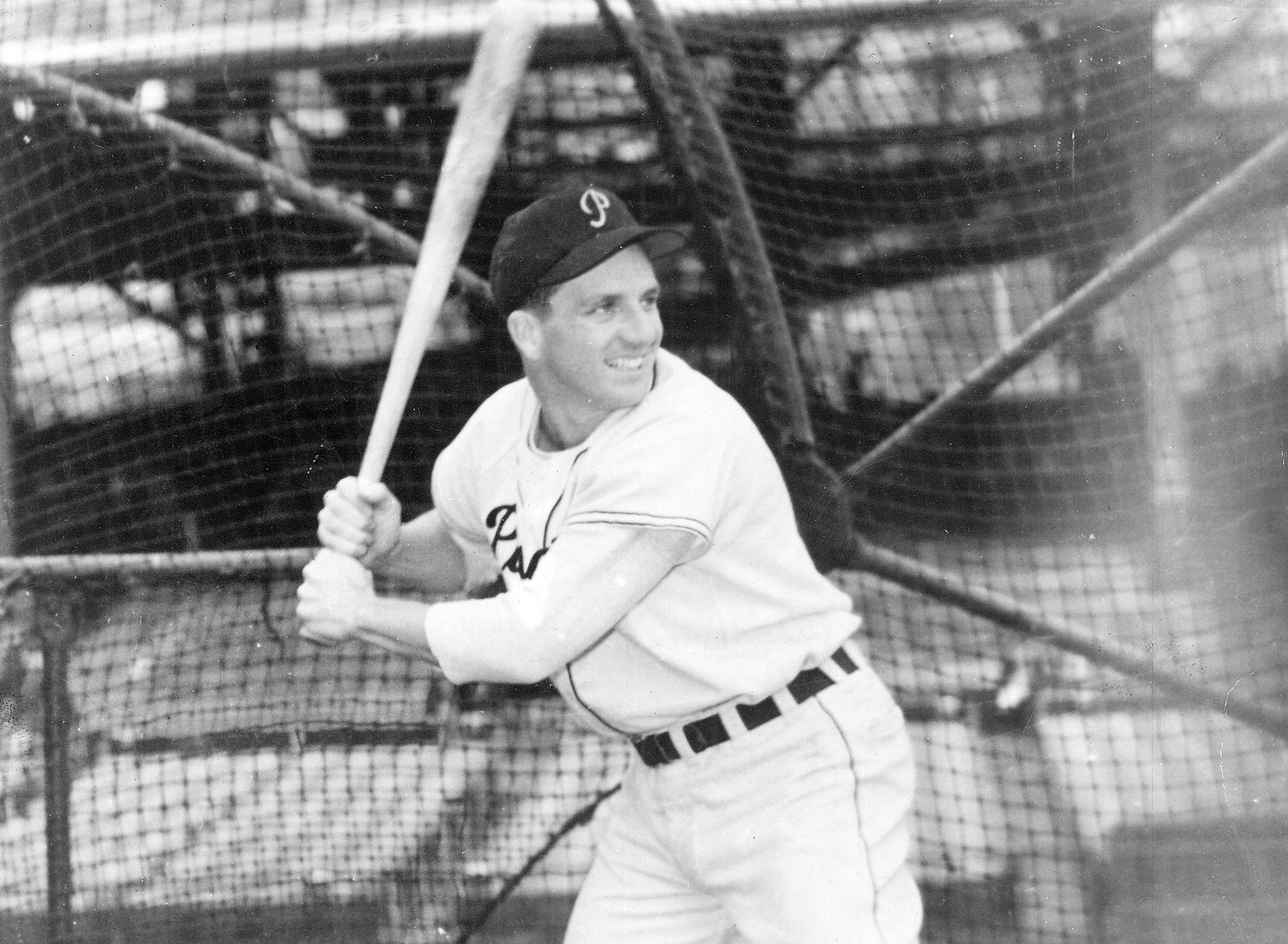

Bernier, after batting .301 with his league-leading stolen base and runs scored totals, was named PCL Rookie of the Year in 1952 with the Hollywood Stars. Apropos of his surroundings, Gilmore Field became a stage with Bernier playing the lead role.

Also one of Hollywood’s most popular players at the time – he met movie stars Marilyn Monroe, Kirk Douglas and Robert Taylor that first year in Tinseltown – Bernier was known throughout the entertainment industry. It’s been said that famed comedian Groucho Marx, when the news broke that the team’s young star had been sent to the National League’s Pittsburgh Pirates prior to the 1953 season, joked that sending Bernier from the first-place Stars to the last-place Bucs would be a demotion.

Joking aside, the 26-year-old Bernier would be showing off his unique skillset while getting his first opportunity in “The Show” with the Pirates during Spring Training in 1953. And following him from Hollywood would be Haney, Pittsburgh’s new skipper.

“If he can hit major league pitching,” Haney said, “he’ll be a sensation. With his speed on the bases and in the outfield the fans will have to go for him.

“If he hits only .275, he’ll be a terrific ballplayer for us.”

Said Johnny Lindell, who played with Bernier in Hollywood in 1952 and joined him with the Pirates: “All he needs is the chance. He might not be a .300 hitter in major league baseball but he won’t be the worst hitter, you can bet on that.”

Also eagerly anticipating Bernier’s big league debut was the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the leading Black newspapers in the country.

“Negro baseball fans,” read the Courier on April 11, 1953, “who have been waiting for a tan baseball star to make an appearance in a Pittsburgh Pirates uniform since the advent of Jackie Robinson into the major leagues in 1947 will have their wishes partially fulfilled this season when Carlos Bernier, brown-skinned Puerto Rican, puts in an appearance at Forbes Field.”

In that same April 11, 1953, issue of the Pittsburgh Courier, the newspaper wrote of other rookie Black ballplayers, besides Bernier, hoping to succeed that season, including Brooklyn’s Jim “Junior” Gilliam, Rubén Gómez of the New York Giants, Milwaukee’s Bill Bruton and Jim Pendleton, Bob Boyd of the White Sox, and Cleveland’s Dave Hoskins.

In a letter to the editor that appeared in the Sporting News after the 1953 season, a reader from Evanston, Ill., wrote: “I was surprised to read that Curt Roberts will be the first Negro to wear a Pirate uniform next spring. Isn’t Carlos Bernier, the outfielder who was with the club the entire ’53 season, a Negro?”

The editor’s note: “Carlos Bernier is a Puerto Rican.”

Despite such excitement towards Bernier and his dark complexion in the Black press, second baseman Curt Roberts, who made his debut with the Pirates in 1954, is considered by the team as its first Black player. But the debate regarding Bernier continues to this day.

And despite platooning in center with the lefty-swinging Felipe Montemayor, Bernier got off to a fast start with Pittsburgh in ’53. The highwater mark of his rookie campaign came on May 2 versus Cincinnati, when he went 4-for-5 with three triples – tying a modern single-game record – and a stolen base. He ended the day with a .385 batting average on the season.

“Everything (went) right,” said a grinning Bernier after the game. “We got (a) swell bunch of players.

“The pitchers aren’t much different here. They have better control and throw more fancy stuff, but I think I can hit them like I did the ones in the minors.”

The confident rookie’s season soon cratered, though, as he was benched and batted only .197 for the remainder of the season.

He ended the year for the last-place Pirates hitting .213 (66-for-310) with 15 stolen bases in 29 attempts.

“I don’t know why,” said Bernier, with a shrug, in a 1964 interview. “Why don’t you ask Fred Haney? All I know is that I was hitting real good, about .385. The last night I played regularly I had four for five, including three successive triples. I never played regularly again. My hitting fell off to .213 and I was sent back to Hollywood.

“Branch Rickey (Pirates GM) came to Haney and told him to lift me from the lineup, he wanted to see another young player under fire.”

Bernier did in fact return to Hollywood and play the next four seasons there. But it was during this latter period that his reputation may have been burnished as not only fleet of foot but also as quick tempered. Some have argued it’s the reason he never played in the big leagues again.

Most notoriously, Bernier was suspended for the remainder of the PCL season after slapping umpire Chris Valenti on August 11, 1954.

“Baseball cannot and will not tolerate umpire assault,” PCL President Clarence Rowland said in a statement. “Bernier used filthy language and also bumped Valenti after being called out on strikes, then slapped him when ordered out of the game. So I am suspending Bernier for the rest of the 1954 season.”

Stars manager Bobby Bragan said after the game: “It’s too bad, for Bernier is the most colorful player in the league. There is no justification, though, for what he did. Carlos is highly emotional and quick tempered. All of us have talked to him several times this year – Branch Rickey included – and each time he assured us he could keep himself in hand. Then he blew his top anyhow.”

According to Bernier: “I have not been well. I was beaned in 1948 and have been nervous and aching in the head ever since. Last year at Pittsburgh I was under doctor’s care and took shots and pills. Not this year, though.”

With a checkered past, one of the most controversial figures in minor league baseball continued his career after Hollywood with successful stops in Salt Lake City (1958-59), Indianapolis (1960-61), Columbus (1960) and Hawaii (1961-64). His final season was spent with Reynoso of the Mexican League, with the 38-year-old batting .281 with 12 home runs in 295 at bats.

“The umpires think I’m a showboat but that’s not true,” Bernier said. “When I play, I play with my heart. That means I play for my ballclub, fight for my ballclub and do everything I can for my ballclub.”

In his prime, Bernier was one of the best players outside of the major leagues despite his temper sometimes getting the best of him. But fans always appreciated his style of play.

“Pitching might be the name of the game as the baseball experts are wont to explain, but color is the synonym for baseball popularity,” explained Dee Chipman of Salt Lake City’s Deseret News and Telegram in 1964. “And they don’t come any more colorful than Carlos Bernier … who’s been the scourge of the Pacific Coast League and high minor leagues elsewhere for the past decade.”

After Bernier died by suicide at the age of 62 on April 6, 1989, his son, Dr. N. Bernier-Collazo, attempted to explain his father’s behavior:

“My father’s only shortfall was that he did not handle the injustices of society with the same grace as a Jackie Robinson or a Roberto Clemente,” Bernier-Collazo said. “I have often wondered how different life would have been for him with all his talents if he had played now (2004) instead of then.

“Despite his extremely competitive demeanor on the field, he was a gentle soul off the field with the greatest qualities – kindness, compassionate, generous, responsible and loving. Many people don’t know what a wonderful person he was because they only witnessed his exploits and his aggressive style of play on the field.”

Bernier’s career statistics in the minors included a .298 batting average, 1,594 runs, 2,374 hits, 1,317 walks and 594 stolen bases.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum