- Home

- Our Stories

- Lyman Bostock remembered for character on and off the field

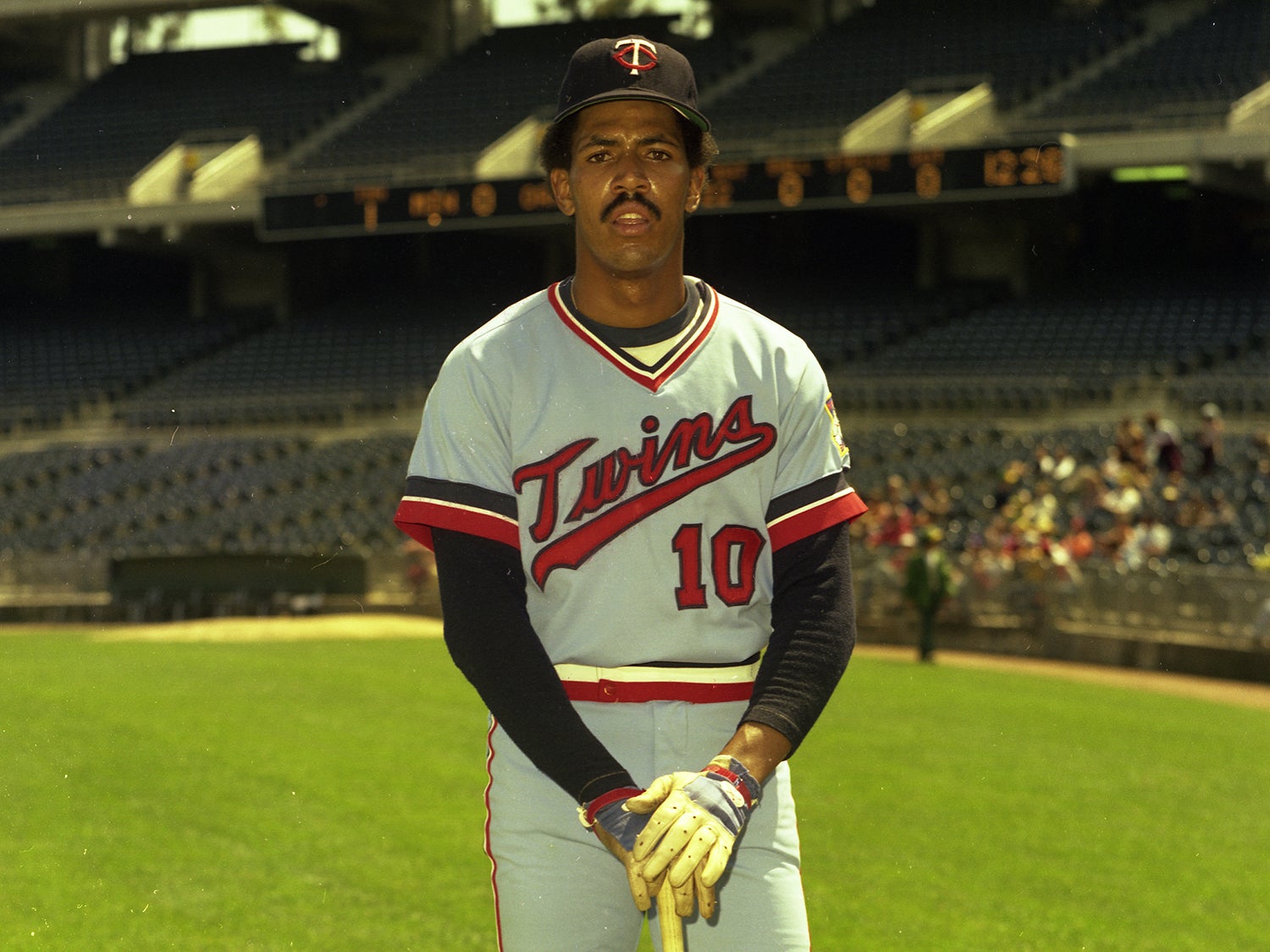

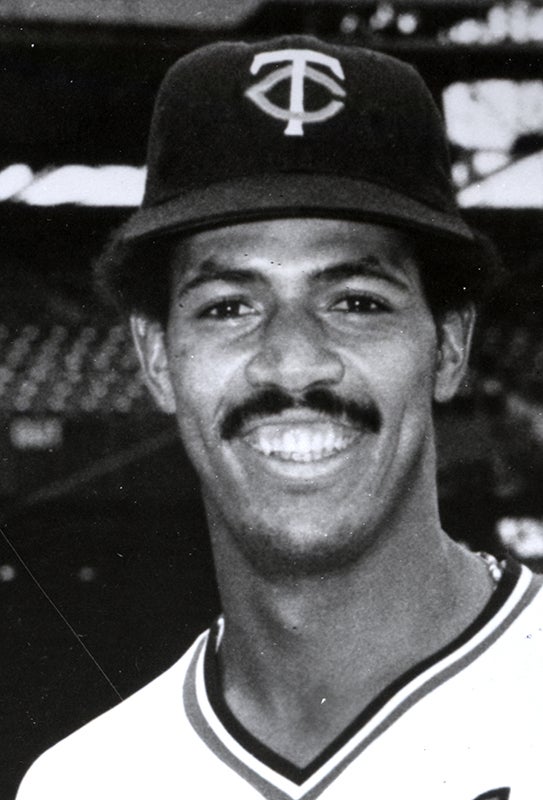

Lyman Bostock remembered for character on and off the field

The name of Lyman Bostock is relatively unknown to younger generations of fans. Even for fans who might have seen him play in the 1970s, the memories of Bostock are most likely scarce. His career – and his life – were simply too short.

Bostock deserves better appreciation for what he accomplished. He was part of a two-generation baseball family, displayed extraordinary all-around talent and showed himself to be a man of character.

Born in Birmingham, Ala., in 1950, Lyman Wesley Bostock came from baseball stock; his father, Lyman Bostock, Sr., had emerged as a star first baseman in the Negro Leagues while playing for Birmingham’s team, the Black Barons. Sadly, the younger Lyman had little contact with his father, who separated from his mother, Annie, just before his birth. Lyman’s mother and grandmother would raise him while struggling to survive financially in Birmingham.

In 1957, with little in the way of job opportunities in Birmingham, Annie Bostock made the decision to move west. With only a few dollars to her name, she and Lyman made the cross-country trek to Los Angeles. That’s where Annie found a better job as a technician in a Los Angeles hospital. She enrolled Lyman in Manual Arts High School, where he became a star at first base, much like his father.

Bostock’s scholastic play drew attention from college coach Bob Hiegert, who was in charge of the baseball program at Valley State College (which was later renamed Cal State Northridge). Playing in the California College Athletic Association (CCAA), Bostock dominated. In 1971, he used his smooth, left-handed swing to bat .344 and earn selection as a second-team conference all-star. He played even better in 1972, this time winning a place on the conference’s first team.

Despite his success, Bostock was mostly overlooked by pro scouts, perhaps because of the CCAA’s status as Division II. There were also unfounded rumors that Bostock displayed a bad attitude at Valley State, something that he always denied. Whatever the reason, Bostock was not selected until the 26th round of the major league draft. That’s when the Minnesota Twins, an aging team that had fallen to fifth place in the American League West in 1971, called his name.

The Twins assigned Lyman to Charlotte, their Class A affiliate in the Western Carolinas League and switched him from first base to the outfield. Bostock showed no power, failing to hit a single home run in 57 games, but did many other things well. He batted .296, compiled a .419 on-base percentage and showed good range in the outfield.

The Twins saw enough to bump Bostock up to Double-A Orlando in 1973. Injuries limited him to 85 games, but he did hit .313, compiled more walks than strikeouts and even hit five home runs.

The following year brought another promotion, this time to Triple-A Tacoma, the Twins’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. Once again, Bostock’s play improved as he moved up to a higher league, a sign of his status as a legitimate prospect. He raised his batting average to .333 and hit seven home runs, earning selection to the PCL’s All-Star team.

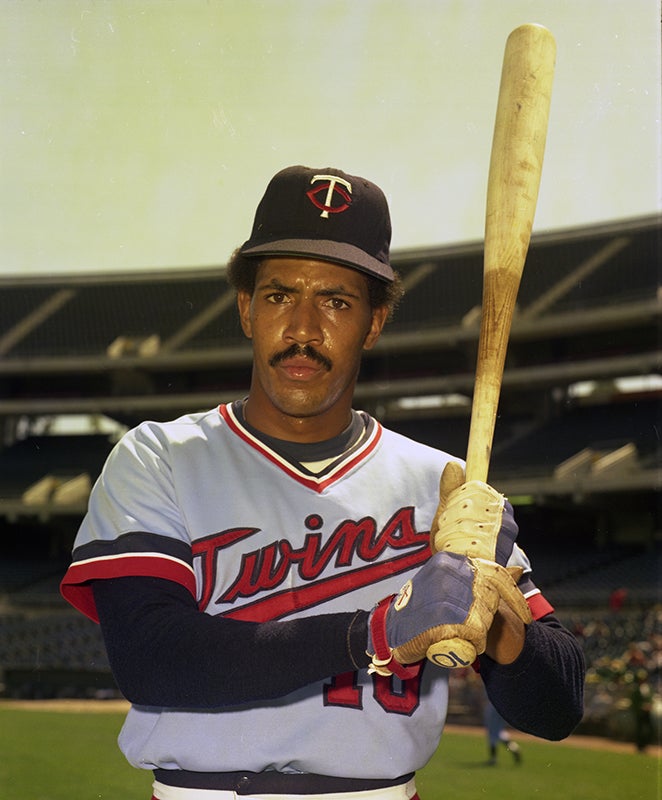

Given his steady climb through the minor leagues, the Twins invited Bostock to Spring Training in 1975 with the idea that he would compete for the starting center field position. Playing in the Florida Grapefruit League, Bostock performed so well that he easily won the job. In fact, his hitting and speed drew comparisons to a veteran Twins player who manned second base: the great Rod Carew. Like Carew, Bostock batted from the left side, used the entire field and opted for hard line-drive contact rather than sheer power. And like his famed counterpart, Bostock could run. He didn’t steal bases as prolifically as Carew did but could take the extra base with Carew-like acumen.

Bostock started for the Twins in center field on Opening Day, but soon fell into a slump, injured his ankle and then received a demotion to Triple-A. Bostock didn’t help matters with an overconfident attitude and his repeated arguing with umpires over balls and strikes. He spent the next several weeks at Triple-A Tacoma, regaining his swing and improving his approach, before being brought back to Minnesota at the end of June. His offensive struggles with the Twins continued until mid-July, with his batting average buried below .200.

Then came the turnaround. By now playing in right field, Bostock went on a tear. It started on July 18 and continued for the rest of the season. During that extended stretch, he batted .323 to lift his season average to .282. Bostock’s overall numbers appeared only modestly good, but his second-half improvement, which came in spite of a thumb injury, gave the Twins a glimpse of his enormous talents.

Bostock also made an impression in the outfield. From time to time, he would make basket catches, in the same style that Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente had used for many years. For Bostock, the basket catch had little to do with Mays and more to do with the lack of proper equipment.

“When I was 8 years old, my mother bought me my first glove, but someone stole it the next day,” Bostock told Twins beat writer Bob Fowler, corresponding for the Sporting News. “My mother wasn’t about to buy me another one. But a friend of hers at work gave her a replacement. Unfortunately, it was a left-hander’s model, and I’m right-handed. Since it was the only glove I had, I had to use it. It was the only way I could catch the ball. It became a habit.”

In 1976, the Twins moved Bostock back to center field and watched him blossom. Toning down his overconfident manner, he batted .323, good for fourth in the American League behind George Brett, Hal McRae, and his teammate Carew. In reaching base 36 percent of the time, he struck out only 37 times. He also played a shallow center field, allowing him to catch fly balls that would have dropped in front of many other outfielders. The only drawback to the season were some injuries, a product of his hard-charging style of play, which limited him to 128 games.

Bostock played so well in 1976 that Fowler, writing for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, made the following prediction: “The Twins will have an excellent center fielder for the next decade.”

Sadly, Bostock would play only one more season for the Twins, and just two more in his entire career.

In 1977, Bostock would lift his game to another level. He posted career highs in just about every major category, including batting average; his .336 mark ranked second in the American League. He reached base at a clip of .389 and stole a career-best 16 bases. He more than tripled his home run production from 1976, finishing the season with 14 longballs. And with 36 doubles and 12 triples, he managed a slugging percentage of .508 and an OPS of .897. Without question, Boston had achieved major league stardom.

But all was not well in Minnesota. In mid-season, Bostock had expressed frustration with Twins fans, calling them “front runners and ignorant” before issuing an apology. With baseball’s new free agent system in place, and Bostock playing out his option, he was due to become a free agent himself. The Twins had tried to sign him during the season, offering him a six-year contract worth $2 million. On the surface, the offer was a good one, but in Bostock’s mind it had come too late, and after too much wrangling with Twins owner Calvin Griffith, a man not known for generosity at the negotiating table. As Bostock once told a Twins reporter: “If it wasn’t for the owner, Minnesota would be a great place to play.”

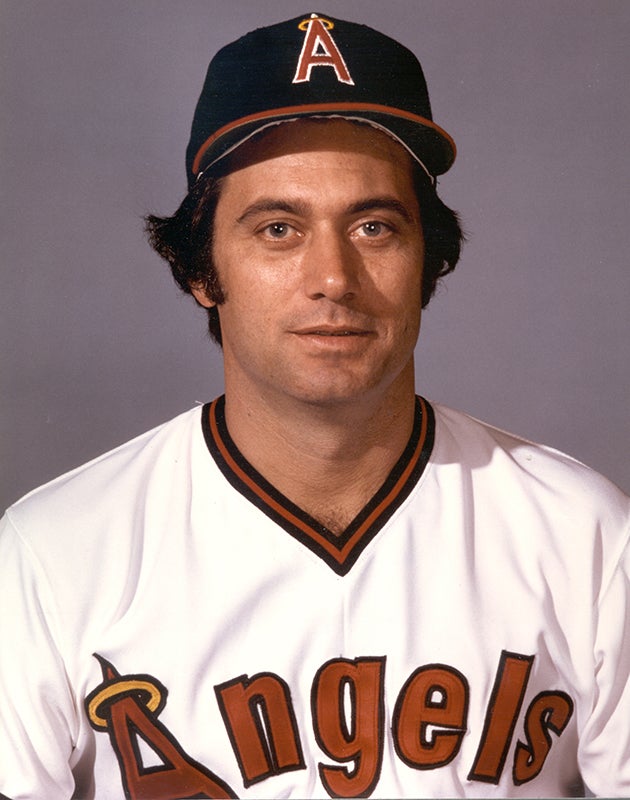

Griffith’s manner left Bostock determined to become a free agent and sign elsewhere. Two teams, the New York Yankees and San Diego Padres, made aggressive offers. The Padres’ deal included ownership in a McDonald’s franchise, courtesy of team owner and McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc. Ultimately, Bostock turned down those offers and signed with the California Angels, whose package of five years and $2.3 million was actually $250,000 less than the Yankees’ offer. Hesitant to join a Yankees’ team that often attracted controversy, Bostock liked the idea of playing in Southern California for another team that was trying to win at all costs, as evidenced by their recent free agent signings of Don Baylor, Bobby Grich and Joe Rudi.

The Angels seemed like the perfect destination. But Bostock, perhaps trying too hard to live up to the expectations that come with a big-money free agent contract, endured a terrible start to the season. Bostock felt so badly about his poor play that he offered to give some of his salary back to Angels owner Gene Autry. When Autry refused to take the “refund,” Bostock gave the money to charity, including a group that helped teenagers in their battles against drug and alcohol abuse. The donation was emblematic of Bostock, who regularly gave sporting equipment to underprivileged children and had established a fund to rebuild the church to which his mother belonged.

Bostock started to play better in June, eventually raising his batting average to the .290s. Then came the horrific events of Saturday night, Sept. 23. After playing in a game against the White Sox at Comiskey Park, Bostock traveled to nearby Gary, Ind., to spend some time with his uncle, Tom Turner. Bostock and Turner then took a ride through Gary, along with two sisters, Joan Hawkins (a childhood friend of Bostock) and Barbara Smith, both of whom had asked for a ride to a friend’s house. As Bostock sat in the back seat at roughly 10:40 p.m. that night, a man named Leonard Smith pulled up alongside the car driven by Turner. Smith, the estranged husband of Barbara Smith, began to argue with the occupants of the car. Turner tried to drive away, but Smith followed him, again pulling up next to the car at a stop light.

At that point, Smith picked up a shotgun and pointed it toward the back window of Turner’s car. Smith, who was known to have stalked his estranged wife and make threats against her, mistakenly believed that she was having an affair with Bostock. He fired into the rear window glass. The blast, which was meant for Barbara Smith, struck Bostock in the right side of the head.

Turner rushed Bostock to a nearby hospital, where doctors worked on him for roughly three hours. But the damage to Bostock was too great. At 1:30 in the morning, Lyman Bostock was declared dead – at the age of 27.

Bostock’s teammate, Danny Goodwin, was the first Angels player to hear about the tragedy. Word soon spread, with Angels slugger Don Baylor and team general manager Buzzie Bavasi making phone calls to let other players know about Bostock. The next day, when a large gathering of media assembled in the visiting clubhouse at Comiskey Park, an angry Baylor shooed away a photographer, telling him to leave Bostock’s locker, which had already been cleaned out.

The news of Bostock’s death left many of the Angels players in tears. While some players found it difficult to talk to the media in the aftermath, veteran Angels outfielder and DH Ron Fairly praised the player who lockered next to him at Anaheim Stadium.

“Lyman was a good man,” Fairly told Angels beat writer Dick Miller. “I felt comfortable around him. When he came into the clubhouse, he always had a smile and a nice word. It sure does take the heart out of you.”

Another Angels veteran shared similar sentiments. “He was a great guy and fun to be around,” said outfielder Rick Miller. “He kept the guys happy.”

With his talkative, outgoing manner, Bostock provided humor, energy, and vitality to the Angels’ clubhouse.

The following Thursday, Angels players, coaches, and manager Jim Fregosi joined Bostock’s widow, Yuovene, and other family members at Bostock’s funeral service. One of the players who spoke at the funeral was veteran left-handed pitcher Ken Brett.

“We have been deprived of a great player, a great friend, and an unmatched spirit has left the Angel clubhouse,” Brett said.

To make matters more difficult, Leonard Smith, the man who murdered Bostock, would spend less than two years in prison. At the trial, Smith was acquitted by a jury, found not guilty by reason of insanity. Smith remained a free man until his death in 2010 at the age of 64.

Bostock’s death was as senseless as it was devastating to his family and the baseball community. There’s no way of knowing what kind of a career he would have had, whether he might have enjoyed a Hall of Fame career or simply a good one, but there is no question that he had a large impact on those who met within baseball. He fulfilled the classic baseball dream: Emerging from poverty to become an acclaimed star, a celebrity within the sport. He did so by working hard and playing the game with intensity and fire, all while giving back to his community, especially when he felt that he had let his team down.

More than 45 years after his death, those are the qualities that sustain the legacy of Lyman Bostock.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum