- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball behind bars

Baseball behind bars

Baseball has long been known as America’s Pastime, and America itself the “Land of the Free.” But what does that mean for those Americans who don’t have their freedom?

There is a long history of baseball teams and even entire leagues being formed within prison walls all across the country from the earliest days of the game itself. Baseball has long been a great equalizer of people, and a symbol of hope and renewal in the darkest times of a person’s life.

In 1914, Sing Sing Prison officials in Ossining, N.Y., recognized this in the inmates under their care, almost all of whom were known to be baseball fans. These officials decided to explore the idea of using baseball as a form of “self-government.” The warden, Thomas Mott Osborne, agreed that “baseball would be the best way of cementing an honor system among the men.” The baseball program was incorporated into Warden Osborne’s Mutual Welfare League, a series of programs designed to boost inmate morale and promote rehabilitation through these self-government principles.

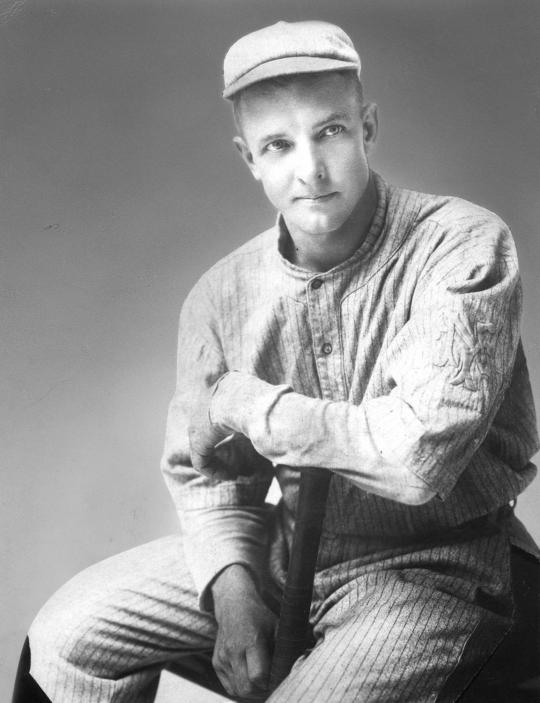

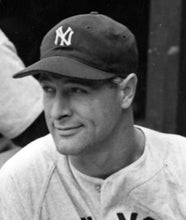

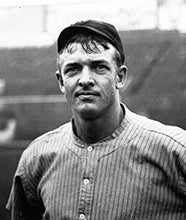

The Sing Sing Prison inmates lost an exhibition game against a team featuring Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig by a score of 17-3, following a particularly outstanding performance by the Babe. The Hall of Famer hit three home runs, one of which, legend has it, traveled 620 feet. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Over the course of the following years, Sing Sing’s tradition of forming and fielding teams made up entirely of inmates became so well-known that the New York Yankees, including Hall of Famers like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, came out to play an exhibition game against the prison’s finest on Sept. 5, 1929. The inmates lost that game by a score of 17-3, following a particularly outstanding performance by the Babe, including three home runs, one of which, legend has it, traveled 620 feet. The New York Times slyly noted that the second of those three blasts “was jotted down by prison statisticians as the longest non-stop flight by any object or person leaving Sing Sing by that route for the past handful of decades.” Ruth also pitched the final two innings for his team in that game, allowing the Sing Sing team a run in each.

Though the papers of the day note the game as having been “chiefly a ball-signing exercise,” exhibition games between inmates and big leaguers like this one show just how important this social experiment became in the lives of inmates and the history of baseball.

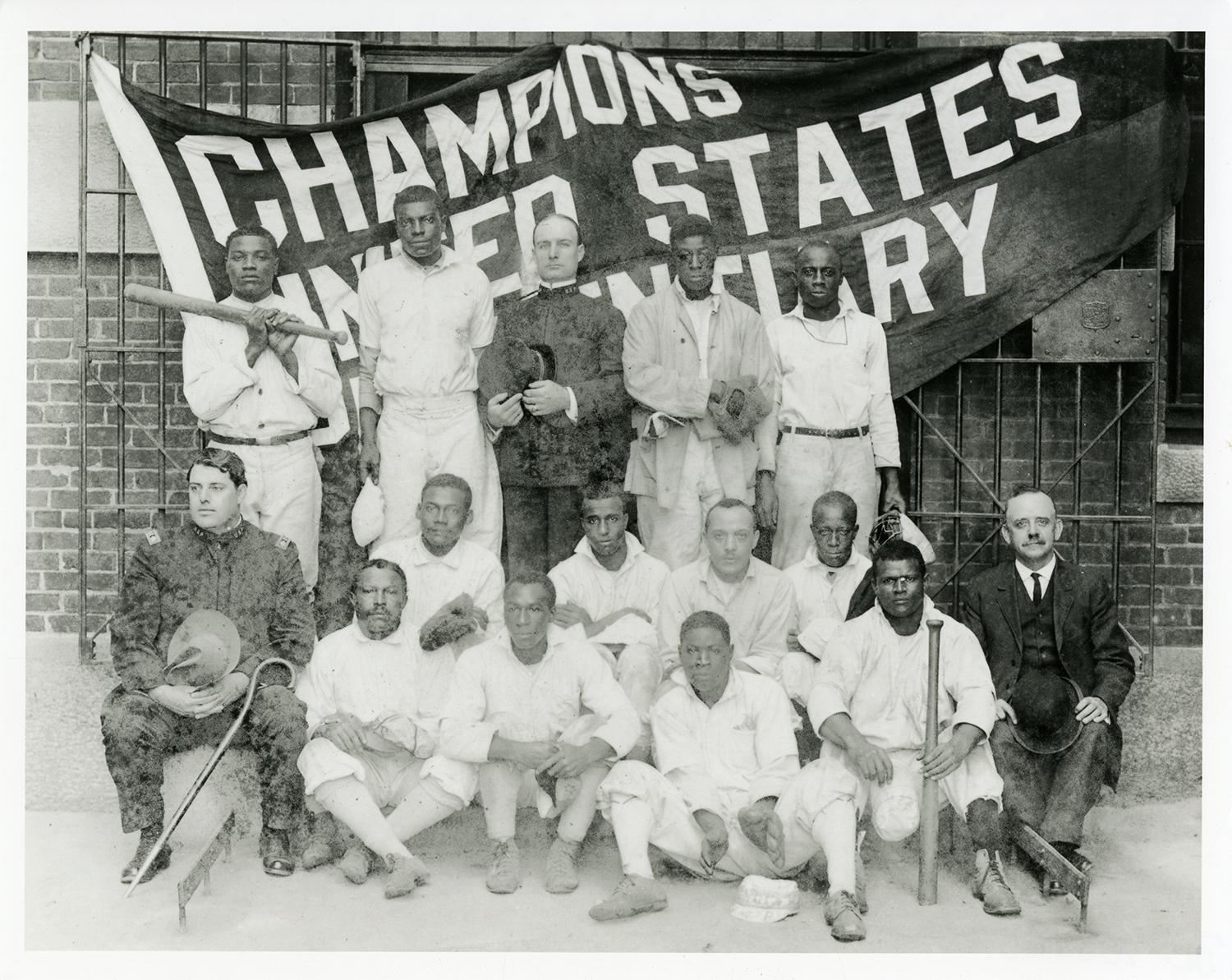

New York was not the only or even the first city to use baseball as a means of rehabilitation in its correctional facilities. As early as 1912, Atlanta fielded teams of inmates for full seasons of baseball. One team, the Giants, even boasted a pitcher known to history only as “Black Matty” (an homage to the great right-hander Christy Mathewson) who was a man who once won 15 straight games. Newspapers and reporters from far and wide covered leagues like these; an April 6, 1913, edition of the Boston Daily Globe told readers that Opening Day at Atlanta’s Federal Penitentiary was “[a]ttended by all the conventional ceremonies of a big league,” including a parade led by a prison band, and the raising of the previous year’s championship flag, won by the Giants, a team of men from the Penitentiary stone-cutting shop.

Prison baseball programs and leagues did not die out after institutions like Sing Sing and Atlanta Federal Penitentiary ceased to field high-profile teams the way they did in the early 20th century. Since 1994, the inmates at California’s San Quentin State Prison have tried out to become a member of either the San Quentin Giants or the San Quentin A’s, their own versions of the Bay Area’s Major League Baseball teams. In fact, prison baseball has been a tradition at San Quentin at least since the 1920s. Every inmate is eligible to make the team, except those on death row or in solitary confinement. San Quentin even brings in “free” teams from local community colleges and other amateur teams to compete against the inmates over their 35-game season.

An April 6, 1913, edition of the Boston Daily Globe told readers that Opening Day at Atlanta’s Federal Penitentiary was “[a]ttended by all the conventional ceremonies of a big league,” including a parade led by a prison band, and the raising of the previous year’s championship flag, won by the Giants, a team of men from the Penitentiary stone-cutting shop. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

It might be easier to write off all of this coverage of prison baseball as media exploitation, but there is something to be said for the real, positive difference baseball made in the lives of the inmates who played on teams and in leagues while they served out their sentences. The Sing Sing baseball program received praise for the “spiritual change in the men” from the likes of Dr. Katharine B. Davis, the Commissioner of Correction of New York City in 1915. Baseball might be “just a game,” but as any fan knows, it is also one of the things that makes life enjoyable.

For incarcerated men since the 19th century, it has been a way to regain some semblance of control in lives that are otherwise devoid of it.

Katherine Adriaanse was a library research intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum