People are always surprised by this rule because no one knows it. Stat geeks were calling me a hero.

- Home

- Our Stories

- Stories of a Scorer

Stories of a Scorer

During the day, Mark Jacobson is a math guy. But for many nights of the year, he gets to be a baseball guy. In addition to covering Washington Nationals games as a freelance radio reporter, since 1992 Jacobson has been an official scorer for the Baltimore Orioles.

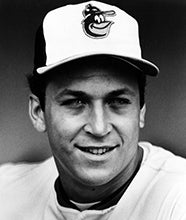

During that time, he scored many of the games that saw Cal Ripken break one of the most “unbreakable” records in sports, made calls that put him in the news alongside Mariano Rivera, and has had a bird's-eye view of the changes to scoring over the years. What has not changed, and what sets scorers apart, he says, is keen, close observation of every move in the game.

Scoring games was originally the responsibility of sportswriters who were given a little extra cash to keep an official record of the game. Official scoring duties in the 1980’s began to move toward dedicated, independent scorers in an effort to keep media outlets and their writers out of the story during controversial calls. Today, official scorers are recommended to and approved by Major League Baseball, a change that brought Mark Jacobson into the job.

After enjoying an exciting Induction Weekend in Cooperstown, Jacobson and his family dropped into the Giamatti Research Center on Monday, July 27, to study the history of scoring and to share their own stories of the profession.

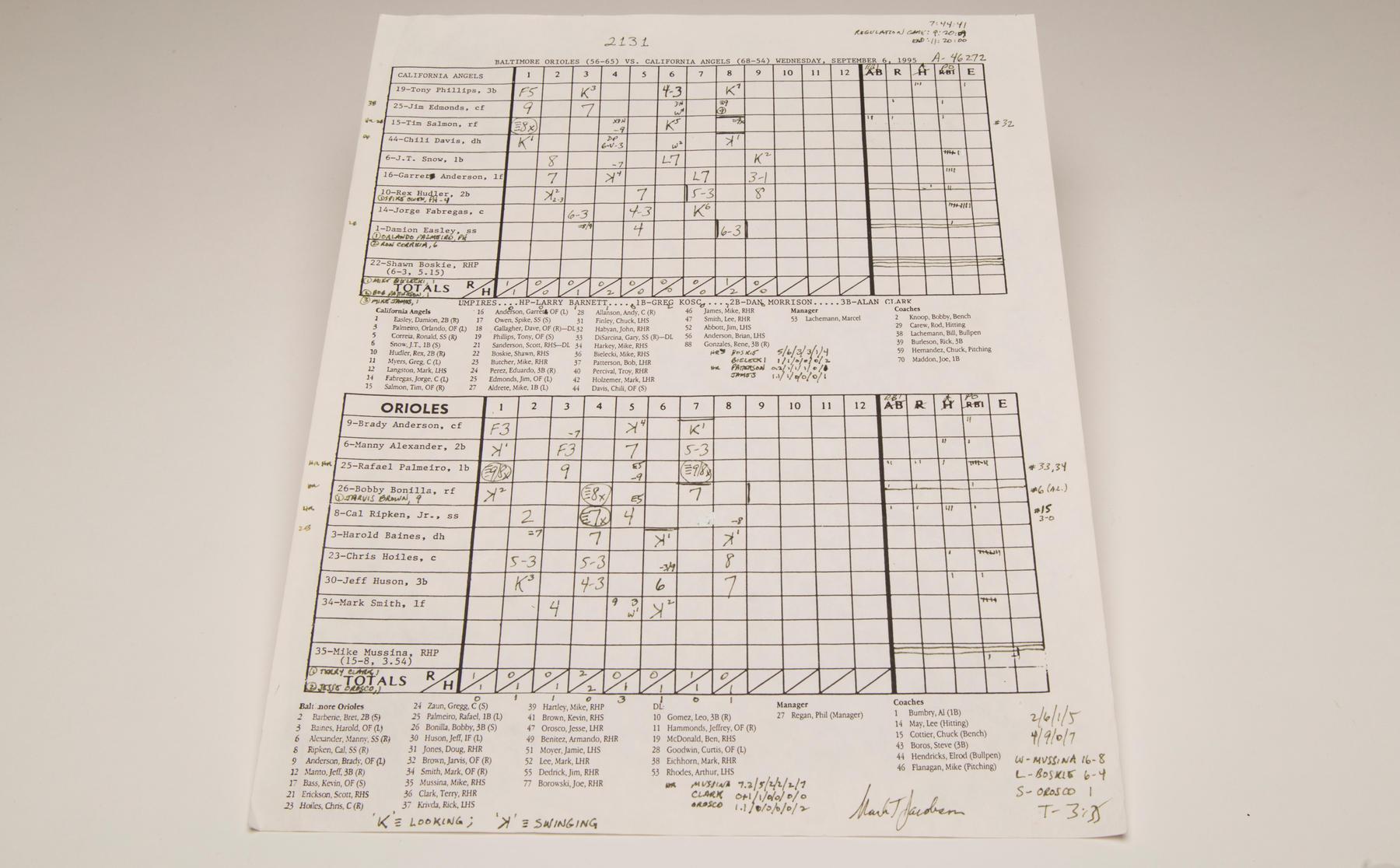

Jacobson is one of dozens of official scorers for Major League Baseball that, along with the American and National Leagues, have donated numerous scoresheets to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Among those scoresheets, is a donation from Jacobson documenting Cal Ripken’s historic “2,131” game.

Becoming a scorer

Like many fans and amateur scorekeepers, Jacobson first learned to keep score as a child at the ballpark.

“I was a Washington Senators fan as a kid ... and as every team did they had a ‘how to score’ page in their souvenir program and I modeled my system off of that, loosely,” Jacobson said. “What I remember mostly was being pretty slow about the clerical aspect. I’d listen to a game on the radio or be at a game there in the park and the game would go too fast for me to record everything.”

By the fifth inning, he would lose interest and often stop keeping score. But as he got older, it helped him to stay better in tune with what was happening during a game.

Later, as a graduate student at Stanford, he covered ballgames in the Bay Area as a radio reporter. It was a chance to get paid for going to games instead of the other way around, and he continued to do so at Baltimore Orioles games after returning to the D.C. area in the early 1980s. His commitment to the sport paid off about 10 years later when the Orioles, in need of a backup scorer, asked Jacobson to fill in.

Staying Neutral

Although Major League Baseball shies away from having official scorers doing double duty as reporters, this independence has not altered the perception that scorers are not impartial observers. In fact, Jacobson said, one of the biggest misconceptions about the profession is that scorers are in the pocket of the home team.

“Scorers tend to be assigned to cities so it’s easy for that perception to arise,” Jacobson said. “There is a presumption that you’re making calls that would favor the home team. We’re not. Let me be unequivocal. I don’t want to do anything other than get the call right.”

Fortunately, an evolving review system is helping to take some of the pressure off.

“In the olden days scorers were kind of imperial … no one could overrule you really. People could ask you why you scored a play the way you did, you were always encouraged to review the videotape … and you have until the day after a game to change a call if you decide you want to but apart from that, other than protesting or making a case nobody could change your call,” Jacobson said.

Around 1998, a review system was instituted where teams, players or scorers could ask a panel of people in the MLB offices to look at a call. This review system is now part of the collective bargaining agreement, creating the ability to appeal a scoring call to the MLB chief baseball officer, a position currently held by Joe Torre.

“It is not a perfect system but … it takes it out of the having to deal with the endless ‘did not, did so’ arguments in the press box because now you send it in, let Joe [Torre] sort it out … and I can go home and not have to worry about whether I’m going to look at that play tomorrow,” Jacobson said.

Getting it Right the First Time

Jacobson said for him the job is easiest when he knows he is making the call he can stand behind. In the end, it is often the official scorer that knows better than anyone what has really happened on the field.

“I think if you are doing your job well as a scorer, no matter how bad your judgment is, you will find that you watch the play on the field more closely than anyone else does because it’s your job to make the call and stand behind it,” Jacobson said. “Everybody in the press box or in the stadium can have an opinion and be confident about it, nobody has to own it.”

One of his favorite examples of this came during Game 3 of the 1996 American League Championship Series between the Yankees and the Orioles.

“A Yankee doubled into the left field corner with Bernie Williams on first and Bernie coasted into third, the batter coasted into second, the throw came into third …Todd Zeile took the throw and with Bernie Williams on third behind him bluffed a throw to second as if he was going to make a play,” Jacobson recounted. “But he held the ball a little loosely or too long and he wound up spiking the ball on the throw he bluffed. It bounced toward left center field, sort of toward shortstop … away from him and Bernie Williams now took off for home plate. Cal Ripken at short scrambled for it and retrieved the ball and made the play fairly close at home, but Bernie slid in safely … Everybody stopped and nobody, cameras included … nobody’s on that and a minute later there is a roar because Bernie Williams has scored on a play that seemingly had ended.”

NBC, who was televising the game, had no footage, but Jacobson had seen every move.

“If you’re doing your job you follow the ball and say it’s a double, no RBI, Williams scored on an error by the third baseman,” Jacobson said. “You hate to be in a position as a scorer where you are saying ‘what happened there’? I won’t say that hasn’t happened, but in that case I was kind of tickled because it took NBC two innings to see if they had an angle.”

Controversial Calls

Scorers also find that they often know the rule book better than many others.

In 2013, not for the first time, Jacobson was put in a situation where he had to invoke a rarely used scoring rule that resulted in controversy, but not in an appeal of his call. He described it as “a perfect storm.”

It was once again the Yankees versus the Orioles during Mariano Rivera’s farewell tour in 2013. David Robertson had come in for New York in the bottom of the eighth with a three-run lead and got rocked, giving up a three-run home run to knot the game at five. In the top of the ninth the Yankees struck back, pulling ahead by one run. For most people in the stands this was the classic Rivera save situation, but that night in Camden Yards would be a bit different.

“There is a little known rule I have had occasion to use a handful of times in 23 or 24 years that says you don’t give a win to a relief pitcher you would otherwise give it to if he is ineffective in a brief appearance [and] if a successor pitches successfully and maintains the lead,” Jacobson said.

He said he could see the whole thing unfolding and could do nothing to stop it, so he collared a team official on his way downstairs and gave him a heads up about what was about to happen. Mariano Rivera went on to do what he did best, shutting down the Orioles in order. As a result of Robertson’s ineffectiveness, Jacobson would cite Rule 10.17(c), awarding Rivera a win rather than a save, drawing an outcry from Yankees fans and media analysts.

“People are always surprised by this rule because no one knows it,” Jacobson said. “Stat geeks were calling me a hero,” he said.

It took about 10 days for the situation to get squared away, and Jacobson has since shared his reasoning and details about instances of the use of Rule 10.17(c) in seminars with other scorers.

Difficult Decisions to Record Breaking Moments

A highlight of Jacobson’s career came on Sept. 6, 1995 when he officially scored Cal Ripken’s 2,131st consecutive Major League Baseball game in which Ripken broke Lou Gehrig’s “unbreakable” streak set in 1939. Jacobson said the entire week leading up to the game was exciting as it came at the end of a nine-game homestand.

“I scored a lot of games that stretch and seeing the visiting teams acknowledge him as they came in – those are things that touch me – when I see other professionals acknowledge their competitors that way,” Jacobson said.

Near the end of Ripken’s 16-year long streak, at the end of the fifth inning, a ceremony was held and a ‘count up’ went up on the warehouse as another start by Ripken became official. On one particular day at the end of the game, Jay Buhner of the Mariners recounted to Jacobson that he had been standing on second and said to Ripken, “am I any less of a man for getting a tear in my eye when I watch that thing drop?” Buhner told Jacobson that Cal responded, “Well how do you think I feel? I’m out here every day when they do that ... why do you think I wear the dark glasses?”

One of the things making it an interesting record was that everyone knew the date it was going to be broken, unlike waiting for a 500th home run or a 3,000th hit.

“You can’t say I’m going to go out and watch Pete Rose break Stan Musial’s National League hits record … well this was ‘on Sept. 6 Cal’s going to do this unless it gets rained out’,” Jacobson said.

Jacobson said it was special for a long time, but like with a no-hitter, he was aware that many things could go wrong to end the streak. Fortunately, for Ripken and baseball fans throughout the country, nothing did.

That September day over 46,000 fans came out to see Ripken pass Gehrig’s 56-year-old record, many of them keeping score the way baseball spectators have been doing for over a century – with paper and pencil. This is the way Jacobson is also likely to continue keeping score in the future as there is evidence that MLB will continue to resist computerizing the official scorer’s report.

This will also help to ensure that handwritten records of unforgettable games like 2,131 will be in places like the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for future generations to enjoy.

Adam Lathrop and Gretyl Macalaster were the 2015 Library-Research interns in the Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum