Viva Espino

Mexico’s Espino personifies much of the Latino baseball story. In the early 1960s, he was a powerful slugger in the Mexican minors who caught the eye of the St. Louis Cardinals. Sold to St. Louis in 1964, Espino went straight to the Cardinals’ AAA-affiliate in Jacksonville, Fla. There he faced many barriers that Latin players yearning to play in the U.S. have encountered for over a century, including differences in language and food, and a lack of cultural understanding that affected both sides. He found that he disliked playing in the U.S., then he decided to do something about it. At the end of the season, Héctor Espino went back home and stayed there.

Espino had options not available to most Latin players. Players like Roberto Clemente, Tony Pérez, and Rod Carew had to play in the U.S. in order to make a living at baseball, and were forced to endure the indignities and discrimination common to American culture of the 1960s if they wanted to succeed. Héctor Espino chose a different way. After the 1964 season, he simply refused to return to the Cardinals.

Because of the unique independence of Mexico’s minor leagues, Espino could resume playing in the Mexican League in summer, the Mexican Pacific League in winter, and earn a healthy paycheck without leaving his homeland. His decision to resist the established system made him a national hero in Mexico, even as it ended his chances for fame in the U.S.

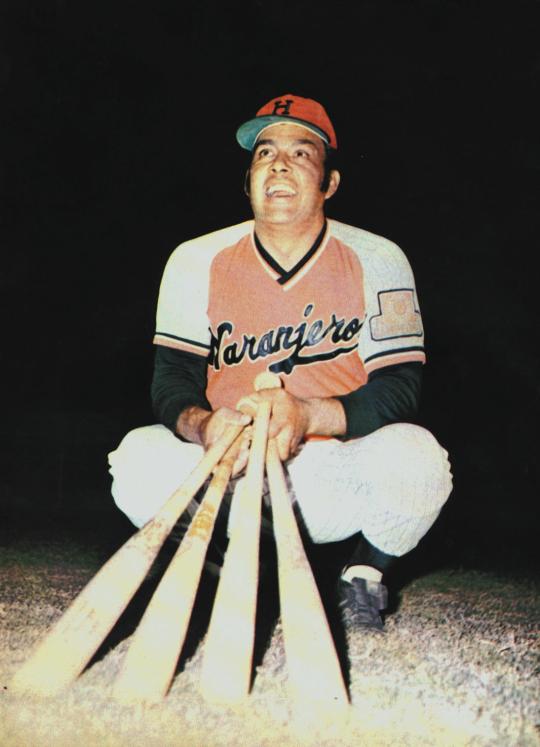

Ultimately, Espino became the all-time home run king of the minor leagues, ripping 453 round-trippers in the Mexican League and another 299 in the Mexican Pacific League. Espino also won numerous batting titles, helped bring eight championships to his Hermosillo Naranjeros, and played seven times in the Caribbean Series, the biggest baseball stage in Latin America. In 1976, he carried the Naranjeros to Mexico’s first Caribbean Series victory and won his second Series Most Valuable Player Award.

For his staggering accomplishments in Mexico and his performances in the Caribbean Series against the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela, Espino earned a place in both the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame and the Caribbean Series Hall of Fame. He is widely considered the greatest Mexican player ever, even though he barely made a mark on the game north of the border.

In 1995, with Espino as a coach, Hermosillo won the Mexican Pacific League championship, earning the club another trip to the Caribbean Series. Although they lost the Series, baseball historian Jorge Colón Delgado recognized the slugger’s tremendous contributions to baseball, sought Espino out, and acquired this Naranjeros jersey from him. In 2008, Delgado generously donated this jersey to the Museum.

Héctor Espino’s experience touches on many aspects of Latin baseball, but additional stories tell us more about our shared Inter-national Pastime. Ultimately, all of these elements pointed to one central truth: Baseball is an integral part of the culture of the Caribbean. It has a long and exciting history that has brought forth, and continues to bring forth, some of the greatest players in the history of the game.

In ¡Viva Baseball!, visitors see how the history of the game differs in each of the major ball-playing areas of Latin America, as well as how other aspects contribute to creating a common Latino baseball experience. Seeking better competition and pay, Latin players encountered many barriers to playing in the U.S., barriers that different players, and different eras, handled in a variety of ways. With the necessary combination of determination and talent, these pioneers ultimately forced baseball to create places for them on team rosters, so much so that today’s fan cannot imagine the majors without Latin American players.

In video interviews located throughout the exhibition, Latin Hall of Famers and current stars share their personal stories, giving Museum visitors insight into topics ranging from fans in the Caribbean to the change in attitudes towards Latin players in the U.S. A video wall presentation shows the passion, joy, and flair that these elite athletes bring to baseball. Ultimately, the exhibition brings the story up to the present, showing the gloves, bats, uniforms and other equipment used by current Latin stars to achieve milestones and set records.

John Odell is the Curator of History and Research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum