- Home

- Our Stories

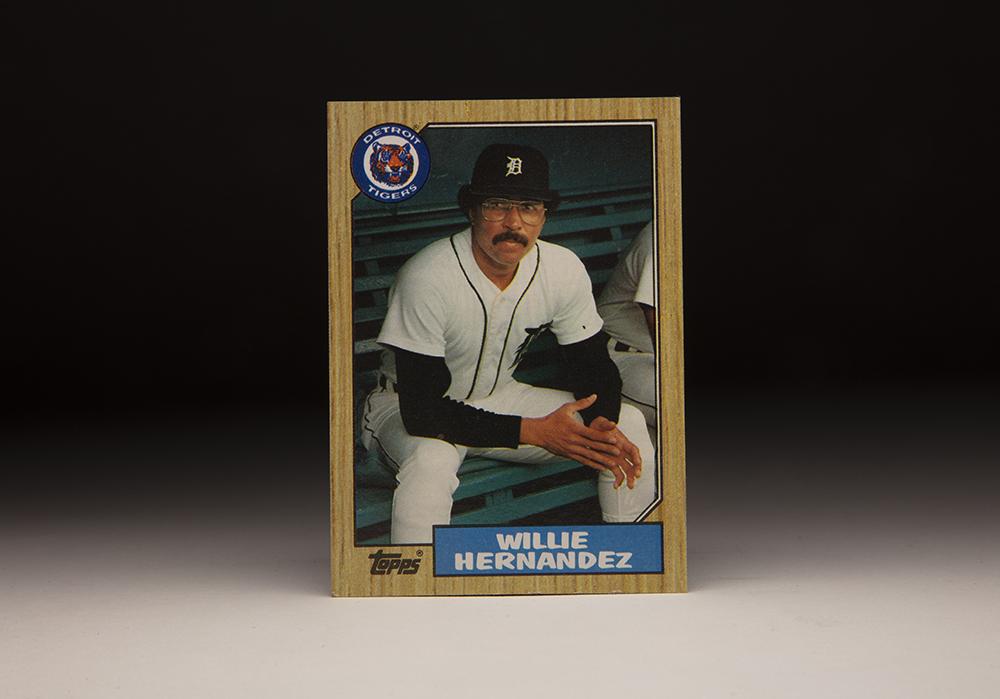

- #CardCorner: 1987 Topps Willie Hernández

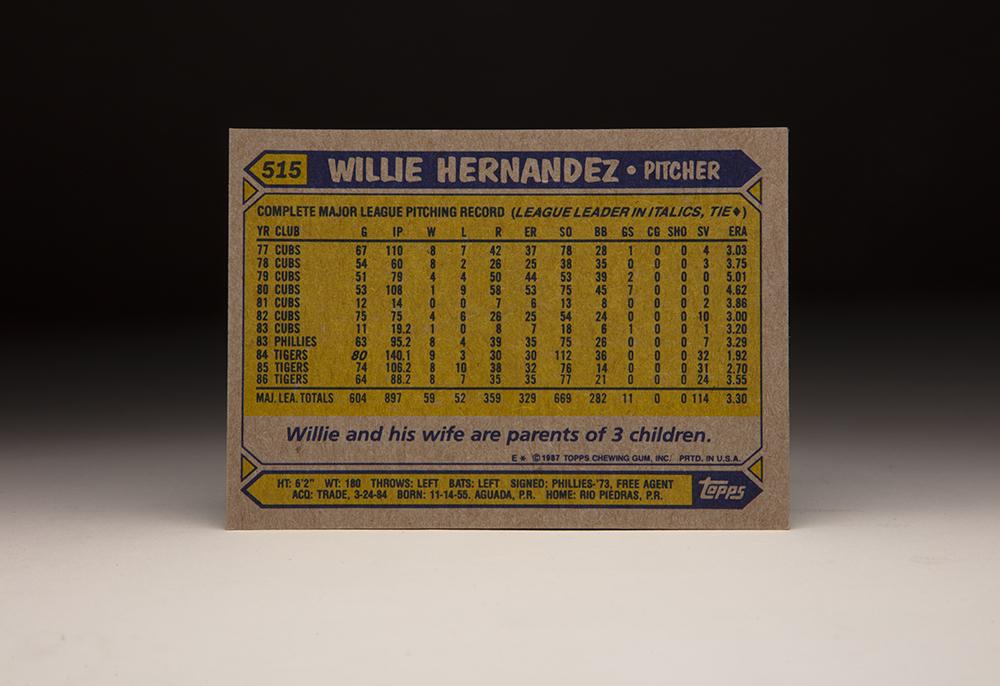

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Willie Hernández

He pitched in the big leagues for 13 years, earning three All-Star Game appearances and saving 147 games.

But Willie Hernández will always be inextricably tied to one great season and one powerhouse team. Perhaps no one player was more responsible for the Tigers’ incredible 1984 run than the screwball-throwing left-hander from Puerto Rico.

Born Nov. 14, 1954, Hernández was raised by a father who labored in a sugarcane mill and a mother who was a hotel maid. He left school at age 15 to come to the United States, where he lived with extended family in Chelsea, Mass., while working in a factory and ferrying auto parts on the side.

At 18, Hernández returned to Puerto Rico and his love of baseball – hurling for local semipro teams. There and while pitching games in Italy, he was noticed by a Phillies scout, who signed Hernández on Sept. 11, 1973 – a little more than two months before his 19th birthday.

“I haven’t worked any harder than my father did,” Hernández told the New York Daily News during the 1984 World Series. “I’ve just been lucky enough to be a baseball player.”

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Hernández made his professional debut in 1974 with Class A Spartanburg of the Western Carolinas League, going 11-11 with a 2.75 ERA while striking out 179 batters in 190 innings. He began the 1975 season with Double-A Reading, going 8-2 with a 2.97 ERA before earning a promotion to Triple-A Toledo. Hernández split the season between the two teams and finished with almost identical records in both places, posting an overall mark of 14-6 with a 3.11 ERA in 171 innings.

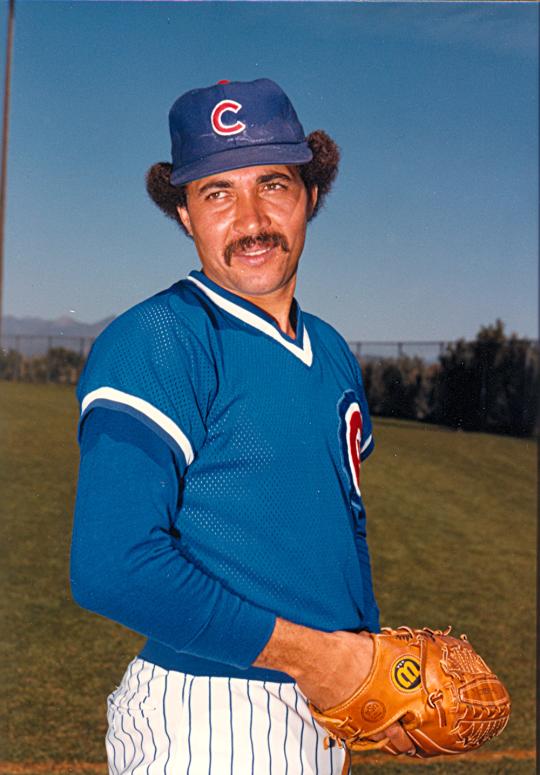

But Hernández spent a month on the injured list in 1976 and wound up with an 8-9 record and a 4.53 ERA over 135 innings with Triple-A Oklahoma City. The Phillies did not put Hernández on their 40-man roster that winter, and the Cubs grabbed Hernández in the Rule 5 Draft on Dec. 6, 1976.

“I had a fastball, a slider and a bad changeup before I came to Spring Training,” Hernández told the Dispatch of Moline, Ill., during the 1976 season. “(But) my curveball is super now. I worked on it in Spring Training with (pitching coach) Barney Schultz. He taught me a lot of things.”

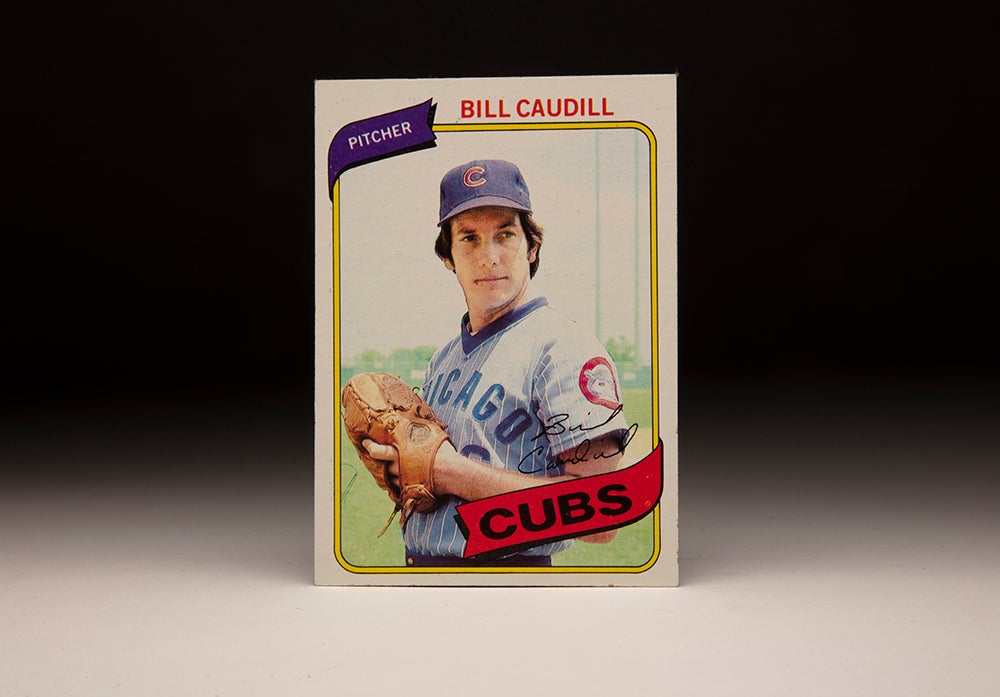

Guaranteed a spot on the Cubs’ roster unless Chicago wanted to risk offering him back to the Phillies, Hernández began the season in the bullpen and was consistently effective. He recorded his first save against the Astros on May 9, notched his first win 20 days later against Pittsburgh and was carrying a 1.88 ERA as late as July 22 before overwork began to take its toll.

“I’ve been pitching a lot, and my fastball is going,” Hernández told the Dispatch. “(The Cubs) want me to get more rest, but when we get behind and we need a left-hander, I can’t just sit on my (butt). I tell you, I’m tired.”

The Cubs won 47 of their first 69 games in 1977 largely due to a bullpen that featured Bruce Sutter, Paul Reuschel and Hernández. But as the season wore on, the pen wore down – though Sutter finished the year with an incredible 1.34 ERA and 129 strikeouts over 107.1 innings, saving 31 games and winning seven more.

“Nobody can pitch like Sutter,” Hernández told the Dispatch. “Sutter just found out the way to throw (the split-fingered fastball).”

But Hernández wasn’t much less effective, finishing with an 8-7 record, four saves and 3.03 ERA over 67 appearances covering 110 innings.

The Cubs toyed with the idea of making Hernández a starter in 1978, and Hernández started a few games during the Puerto Rican Winter League season that year before injuries forced him to stop throwing. But when he reported to Spring Training in 1978, Cubs manager Herman Franks immediately reinstated Hernández in the bullpen.

“Right now, I enjoy the bullpen more than starting,” Hernández told the Chicago Tribune. “From the bullpen, you face the best of situations. It’s very exciting.”

But Hernández’s arm was still not responding at the start of Spring Training, and he didn’t make his first Cactus League appearance until March 21, 1978. Shoulder woes sidelined him for three weeks in late June and early July, and Hernández finished the season with an 8-2 record, three saves and a 3.77 ERA over 54 appearances. His 59.2 innings were barely half of what he worked in 1977.

In 1979, Hernández allowed three earned runs without recording an out on Opening Day against the Mets and then surrendered seven hits, seven walks and six earned runs over 2.2 innings in an epic 23-23 loss to the Phillies on May 17 at Wrigley Field. A dejected Hernández was pictured on the front sports page of the Chicago Tribune the following day, and he was unable to ratchet down his ERA for the rest of the season – finishing with a 4-4 record and 5.01 ERA in 51 games.

The following year, the Cubs tried Hernández as a starter – moving him into the rotation in May before a couple rough outings, including one where he walked eight Padres over four innings, convinced the team he should return to the bullpen. He pitched in mop-up duty for most of the year, enduring a 32-game stretch from May 6 through Aug. 15 where he appeared in just one game that the Cubs won.

Hernández finished the year with a 1-9 record and 4.40 ERA over 53 games.

In 1981, Hernández did not make the Opening Day roster for the first time since joining the Cubs and was sent to Triple-A Iowa. He was recalled briefly in June but did not appear in a game before heading back to Iowa – then resurfacing in late August. He went 4-5 with a 3.89 ERA for Iowa as a spot starter/reliever before making 12 appearances with the Cubs late in the season, posting two saves with a 3.95 ERA.

After five seasons in the big leagues, Hernández’s career was at a crossroads.

“I don’t deserve all the boos,” Hernández told the Chicago Tribune in 1982 after three seasons of being targeted by fans. “But when they boo me that makes me happy – because I’m going to show them they’re wrong.”

Hernández did indeed turn his career around in 1982, earning an Opening Day spot with the club and working 17 games in May alone – including appearances in five straight contests from May 1-5. He finished the season with a 4-6 record and 10 saves over 75 appearances, posting a 3.00 ERA over 75 innings.

Hernández said he benefitted from advice from Orlando Cepeda during the Puerto Rican Winter League season of 1981-82.

“Orlando told me how hitters think, how they worry,” Hernández told the Chicago Tribune. “I see now that it’s the pitcher who’s really in charge, not the hitters.”

Then during the Puerto Rican Winter League season of 1982-83, Hernández got some more advice that would change his career. Mike Cuellar, the 1969 American League Cy Young Award winner and one of the aces of the great Orioles staff during the late 1960s and early 70s, introduced Hernández to the screwball.

“Mike Cuellar showed me how to throw it in Puerto Rico and he had a heckuva screwball,” Hernández told the Morning News of Wilmington, Del., in 1983. “I feel I can throw it for strikes most of the time.”

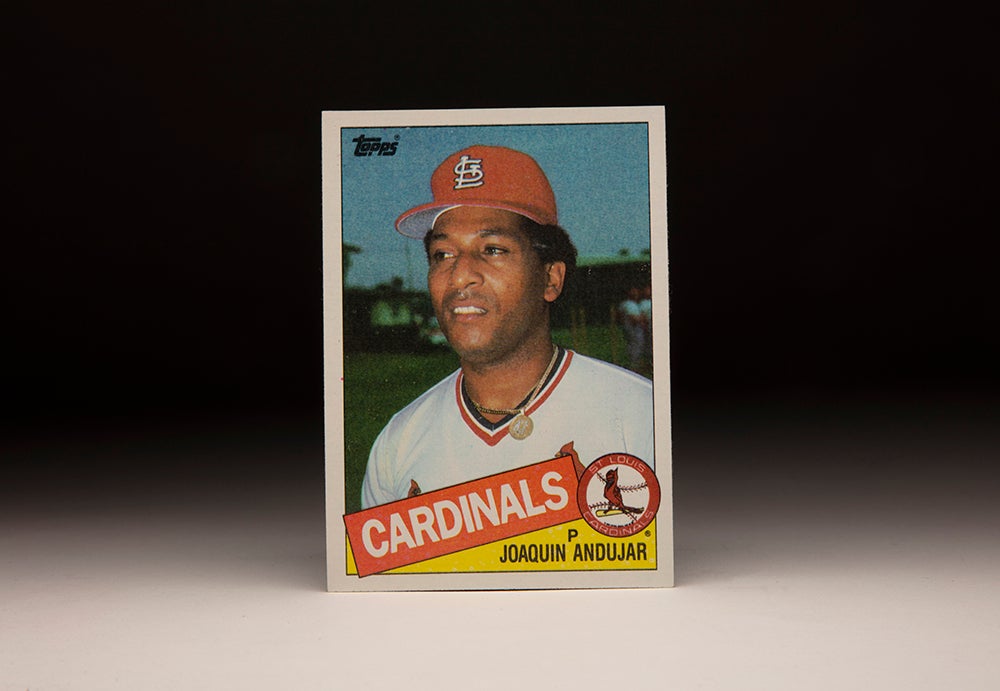

Hernández unveiled the new pitch in Spring Training of 1983. But the Cubs – seeking a veteran starter – dealt Hernández to the Phillies on May 22, 1983, in exchange for Dick Ruthven and Bill Johnson.

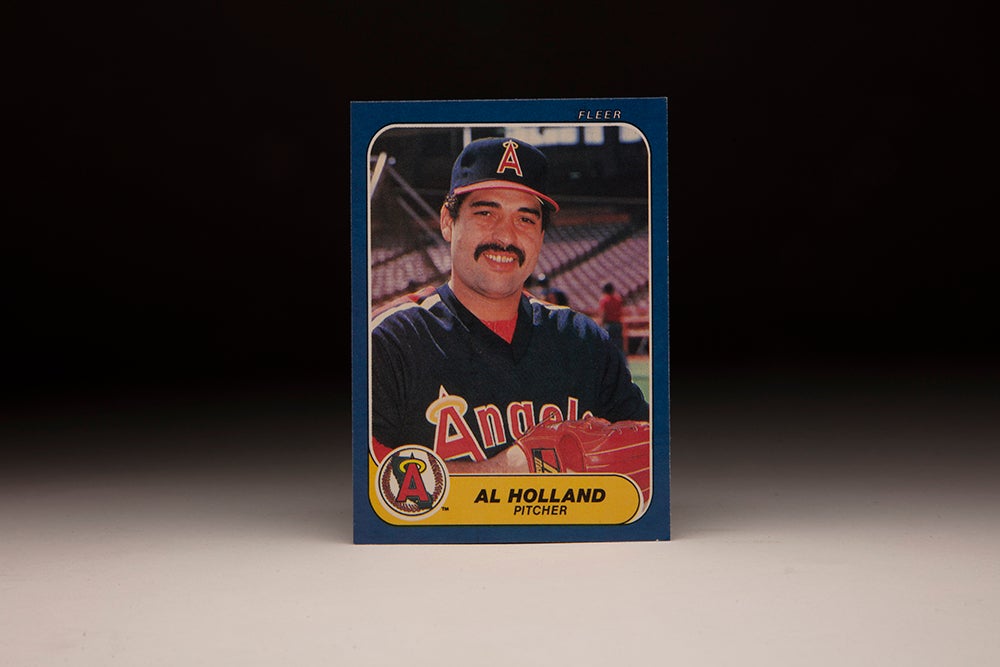

Suddenly, Hernández found himself with a contender. Energized, Hernández allowed no earned runs in 16 of his first 17 appearances for the Phillies. With Ron Reed and Hernández serving as reliable set-up men for closer Al Holland, the Phillies recovered from a slow start to win the National League East. Hernández finished the season with a 9-4 record, eight saves and a 3.28 ERA over 74 appearances.

Hernández did not appear in the Phillies’ 3-games-to-1 win over the Dodgers in the National League Championship Series. But he made his first-ever postseason appearance in Game 2 of the World Series against the Orioles. It was a frightening moment for Hernández, who hit Baltimore’s Dan Ford – the second batter he faced – in the helmet with a pitch in the fifth inning. Ford, a right-handed hitter, had seen a screwball on the previous pitch and dove out over the plate in anticipation of another one fading away from him. The ball smacked Ford on the bill of the helmet, which flew off Ford’s head. Ford, however, remained in the game.

“That worried me,” Hernández told Knight Ridder Newspapers. “That’s why I ran in from the mound. I’ve never hit anybody in the head.”

Hernández retired the Orioles without allowing a run but was removed in favor of pinch hitter Von Hayes in the sixth inning. The Phillies lost the game 4-1 and dropped the series in five games, losing four in a row after winning the opener. Hernández pitched in Games 4 and 5, not allowing a hit or a run over his four total innings of work.

It would be a taste of things to come in 1984.

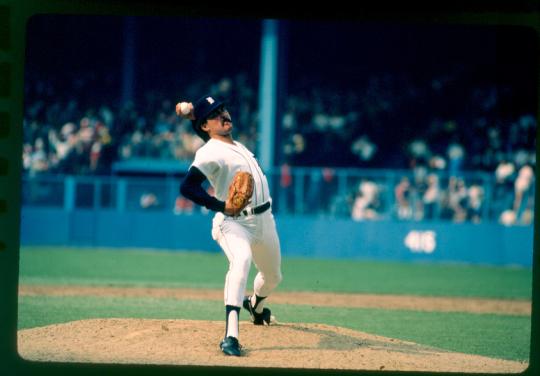

On March 24, 1984, the Phillies, Giants, and Tigers consummated a three-way trade that sent Hernández and Dave Bergman to Detroit.

“This was a tough decision because we’re giving up Hernández, one of the better relief pitchers around,” Phillies manager Paul Owens told the Associated Press.

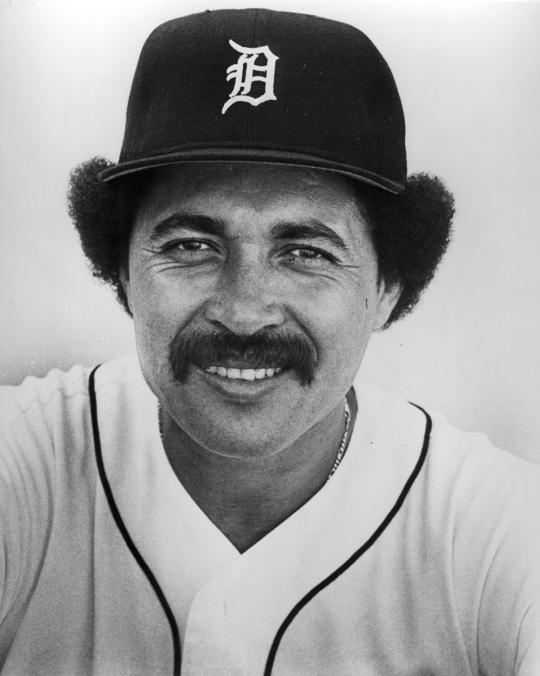

One of the better relief pitchers around became the best in the game that season. Detroit rocketed to a 35-5 start, with Hernández going 1-0 with seven saves in that stretch. As the summer wore on, Hernández became more effective – posting 15 saves and four wins from June 8 through Aug. 4 without a loss or blown save in that period.

Hernández was not charged with a blown save until the Tigers’ 160th game of the season – by which point Detroit had long ago wrapped up the American League East title. Hernández led the majors with 80 appearances and 68 games finished, totaling 32 saves to go with a 9-3 record and 1.92 ERA while working 140.1 innings and earning his first All-Star Game selection.

Among pitchers with zero games started in a season, Hernández’s innings total has only been topped once since – by Toronto’s Mark Eichhorn in 1986.

The postseason became almost a coronation for the Tigers and Hernández, who won seven of the eight games they played. Detroit swept Kansas City in the ALCS, with Hernández working all three games and picking up a save. In the World Series against the Padres, Hernández allowed just one run in 5.1 innings over three games, retiring Tony Gwynn on a fly ball to end Game 5 and the series by notching another save.

Two weeks later, Hernández was named the American League Cy Young Award winner.

“I thank Sparky Anderson for giving me the chance,” Hernández told United Press International after winning the award. “Sparky gave me the ball every single day to do what I did this year.”

A week after that, Hernández became the third reliever – following Jim Konstanty in 1950 and Rollie Fingers in 1981 – to win his league’s Most Valuable Player award.

“It was unbelievable. It was like I have another win, like winning the World Series again,” Hernández told the Associated Press after being named MVP. “Winning these two awards in the same year for a relief pitcher…it’s kind of difficult, kind of impossible.”

Following the World Series, Hernández exercised an option in his contract demanding the Tigers trade him by March 15, 1985. But the move was strictly procedural to speed up negotiations on a new deal.

“I don’t want to leave Detroit,” Hernández told UPI. “I want to share my future with Detroit. I believe we have the ballclub to win a lot more. I want to stay there.”

Right before the deadline, Hernández and the Tigers agreed to a four-year, $4.7 million extension that made him the Tigers’ highest-paid player and carried him through the 1989 season.

The Tigers were unable to duplicate their championship ways in 1985 but Hernández was still very effective, going 8-10 with 31 saves and a 2.70 ERA in 74 games. He lowered his WHIP from 0.941 in 1984 to 0.900 – becoming just the second reliever in history with two straight seasons of at least 100 innings pitched, a WHIP of less than 1.000 and zero starting assignments. Only Hoyt Wilhelm (1964-65) and Bruce Sutter (1977 and 1979) have as many as two similar seasons.

But after a stretch in August where he was tagged with five losses in 14 days, Tigers fans began booing Hernández. Coupled with several minor injuries – including bruised ribs suffered in a fall at his home – Hernández began to feel the strain of his huge contract.

“He takes it all so personal – I’m really concerned about what it is doing to him,” Anderson told the Detroit Free Press. “After it became apparent (in 1985) that we weren’t going to repeat, (the fans) had to take it out on someone, and Willie was handy because he’s always in there when the game is on the line.”

The booing increased in 1986 when Hernández went 8-7 with 24 saves and a 3.55 ERA – earning his third straight All-Star Game selection. But shoulder pain forced Hernández to skip the Mid-Summer Classic, prompting more criticism from fans.

Then in 1987, the Tigers returned to the top of the AL East with 98 wins despite more injuries and ineffectiveness for Hernández. He finished the season with a 3-4 record and eight saves in 45 games – allowing three earned runs over his last four appearances where he recorded just one out.

But in the ALCS vs. the Twins, Anderson turned to Hernández in Game 1 with the game tied at five and the bases loaded with one out. Hernández promptly allowed an RBI single to Don Baylor and a two-run double to Tom Brunansky that carried Minnesota to an 8-5 victory.

Hernández would not pitch again in the series, which Detroit lost four-games-to-one.

“The whole season has been a disaster,” Hernández told the Detroit Free Press following Game 1. “Mentally, I’m trying to keep my confidence. I’m not a quitter.”

Following the season, Hernández asked for a trade.

“I feel like I’ve been pitching against the American League and the fans this year,” Hernández told the AP. “If it’s going to be this way here next year, well, I’ll leave that frustration to someone else.”

But the frustration continued. On March 2, 1988, Hernández dumped a bucket of ice water on writer Mitch Albom, who had written a story 11 months earlier on Hernández’s battles with the fans. Anderson transitioned Hernández into a set-up role that year and installed Mike Henneman as closer – with Hernández finishing the season with a 6-5 record and 10 saves in 63 games.

In 1989, however, an elbow injury limited Hernández to 32 appearances. He totaled 15 saves but posted a 5.74 ERA. With his contract expired, the Tigers officially released Hernández on Dec. 20.

Now known as “Guillermo”, Hernández spent time as a non-roster player with the Athletics in the spring of 1990 and a year later with the Phillies. But no offers were forthcoming, and Hernández hooked on with Toronto later in 1991 and pitched eight games for the team’s Triple-A affiliate in Syracuse, N.Y.

Hernández then made another comeback attempt in 1995 as a replacement player with the Yankees during the strike. But when the work stoppage ended, Hernández was sent to Triple-A Columbus, where he posted a 7.67 ERA in 22 games in the final appearances of his career.

In 13 big league seasons, Hernández went 70-63 with 147 saves and a 3.38 ERA in 744 games. He remains one of only three relievers – along with Rollie Fingers in 1981 and Dennis Eckersley in 1992 – to win a Cy Young Award and Most Valuable Player Award in the same season.

“I’ve learned you can’t be a big-headed guy,” Hernández told AP following his unforgettable 1984 season. “I am the same. My attitude is the same.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum