Sutter remembered as pioneer of split-fingered fastball

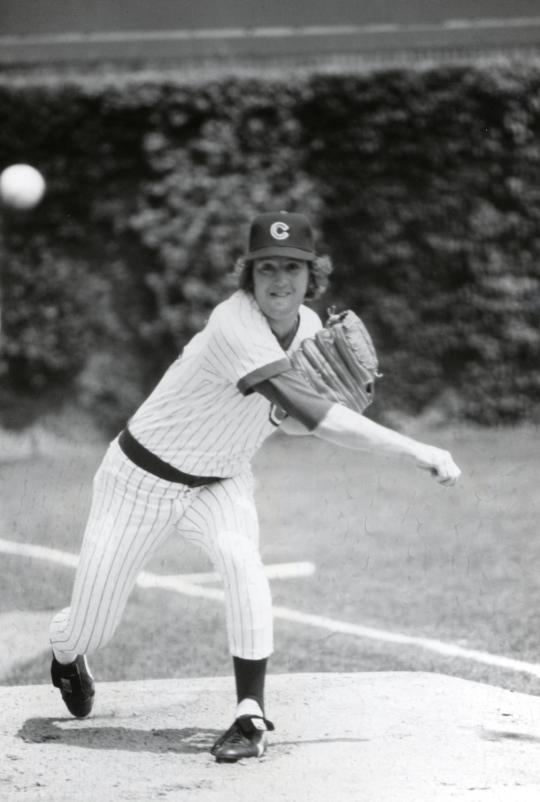

Bruce Sutter’s entire career can be boiled down to about an inch of white leather and red stitching.

By spreading his index and middle fingers farther apart on the ball when he pitched, the right-hander developed a split-fingered fastball that stunned opposing batters and gave him a second chance at the game he loved before his Major League career even began.

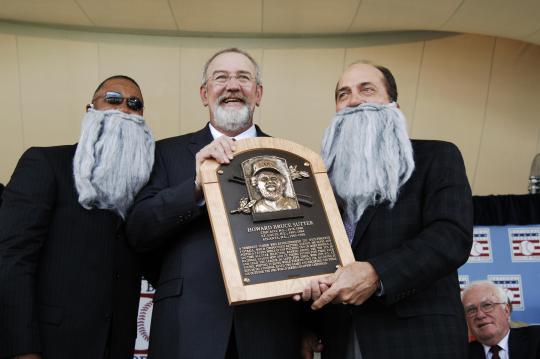

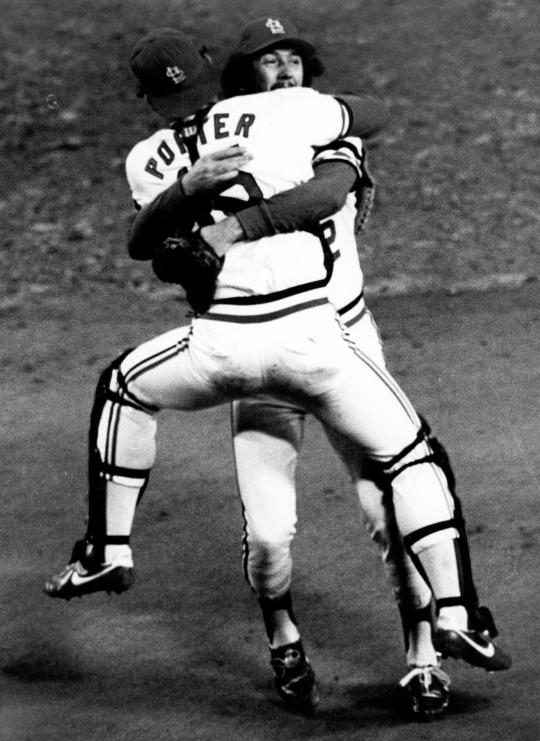

Twelve years in the majors and 300 saves later, Sutter had become one of the most dominant relievers of the late 1970s and early 1980s, all because of a different grip on the ball. His success earned him a World Series ring in 1982 and enshrinement in Cooperstown in 2006.

Sutter, 69, passed away on Oct. 13, 2022. During his career, he fought through devastating elbow and shoulder injuries and underwent three surgeries, yet retained his calm demeanor and ability to stay poised under pressure as he became the first pitcher to lead the National League in saves five times.

“Bruce Sutter was so honored when he was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2006, and since that time his kindness, his love for Cooperstown and his humility sparkled every time he returned to the Hall of Fame,” said Jane Forbes Clark, Chairman of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “The Hall of Fame family will forever celebrate his achievements on the field and remember his passion for his family and friends. We extend our deepest sympathies to his wife, Jamye, and his children.”

Howard Bruce Sutter was born in Lancaster, Pa. on Jan. 8, 1953. He was a three-sport athlete in high school, excelling as captain of both the football and basketball team while leading the baseball team to a county championship.

The Washington Senators selected Sutter in the 21st round of the 1970 draft, but because he was not yet 18 years old he was unable to sign a contract. He spent the next year pitching in semipro leagues around his hometown before the Cubs signed him as an amateur free agent on Sept. 9, 1971.

Eighteen years later, Sutter received a call in January from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, informing him of his election to the Hall of Fame. It was his 13th time on the ballot, and the player who had once known for taking the mound with little emotion was suddenly overcome.

“I started crying,” Sutter said. “It was a call you always hope for but never really expect to happen. When it did, I didn’t think it would affect me or hit me as hard as it did, but it sure did.”

Sutter was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2006 as the first pitcher without a single starting assignment to be elected.

“The call answered a question that had been ongoing for 13 years, a question – quite frankly – I would ask myself every year at election time: Do you belong?” said Sutter.

While his induction proved that he did indeed belong among baseball’s greats, Sutter also found he belonged outside of baseball. After his retirement, he focused on raising his family. He resurfaced for a brief part-time coaching stint in the Cardinals’ organization, but eventually chose to leave baseball for his wife and children.

“Once I was done playing, I walked away,” Sutter said. “I wanted to be with my boys.”

Sutter’s legacy will forever live on in the split-fingered fastball, which has since become a prominent pitch at every level. As a pioneer of the pitch, Sutter paved the way for the many pitchers who throw splitters today.

“Every baseball player wants to be remembered,” Sutter said, “whether it’s for a pitch or a play or a season.”