Baseball came of age during American Civil War

As the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Chief Curator for 28 years, Ted Spencer experienced history every day. But one day in the early 1990s, he was amazed to discover just how strong the tie is between baseball and America’s history.

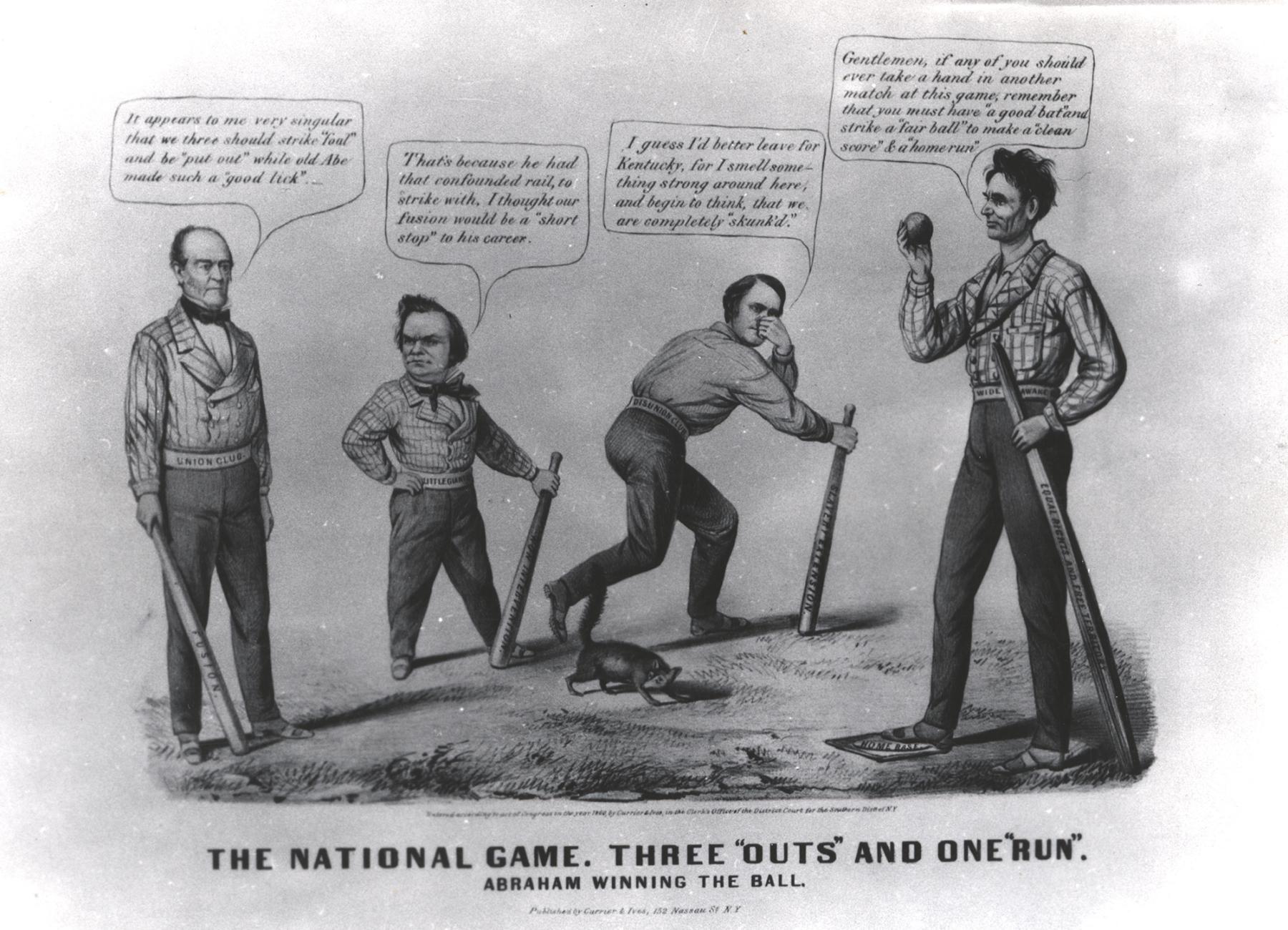

Spencer had seen a Currier & Ives lithograph– an original of which resides in the Hall’s collection – several times before, but it wasn’t until that day that it piqued his curiosity.

“When I looked at it, I started to wonder what it was all about,” Spencer said.

Spencer showed the lithograph to his eldest son – then in middle school. His son had a passion for American history and was able to decode the political cartoon for his father. The lithograph – published just months before the 1860 election – depicts Abraham Lincoln playing baseball against his rival candidates – John Bell, Stephen A. Douglas, and John C. Breckinridge. Lincoln has hit a home run using a bat representing his party’s platform, while the others have all been called out using much weaker bats.

“To me it was an epiphany,” Spencer said. “I began to appreciate the relationship between the game, our country and our history. Currier & Ives were looking for a vehicle to explain a complicated political message, and they felt people would understand it best in baseball terms.”

Even in the Civil War, baseball was a central part of American culture.

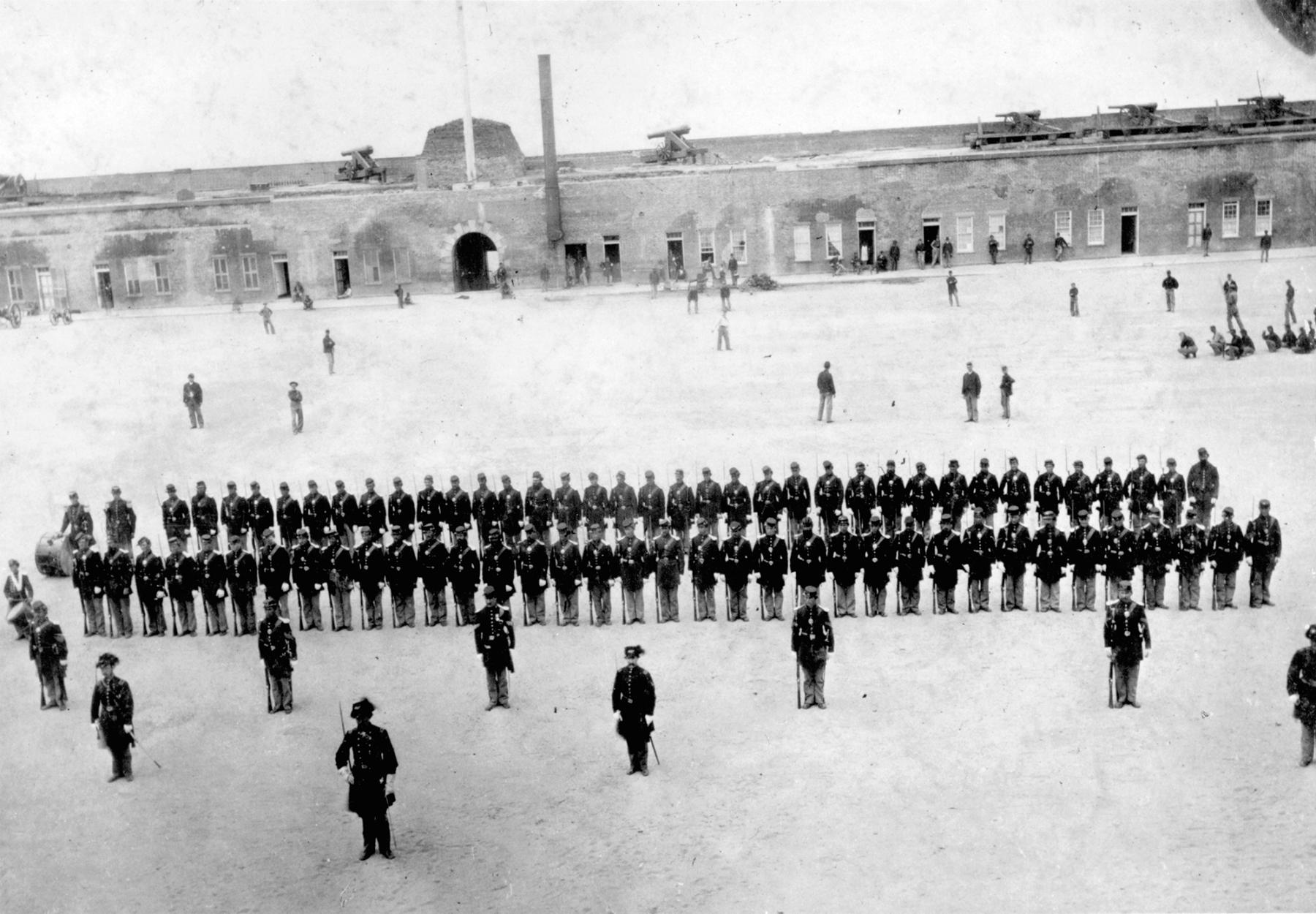

By this time too, the New York Game (or National Association Game, as it was known by then) had begun to assert its dominance over other variations. During the war, baseball served an important role in American culture. On the home front in northern cities, it remained a popular leisure activity that entertained the masses. On the front lines, baseball became an important diversion for the more than three million Americans serving in uniform on both sides.

Civil War soldiers faced many hardships, including the possibility of death in battle or from disease. They also struggled with the tedious monotony of camp life. While not actively campaigning, soldiers on both sides sought diversions to pass the time. Many soldiers read newspapers and books, wrote letters home or enjoyed music. They also participated in sports and games.

Commanders and army doctors encouraged these physical activities, believing that they kept the soldiers fit and healthy, while also keeping them out of trouble. While soldiers frequently took part in foot races, wrestling and boxing matches, and occasionally even cricket or football, noted Civil War historian Bell Irvin Wiley has stated that baseball “appears to have been the most popular of all competitive sports” in the camps of both armies.

Civil War veterans have left us accounts of playing baseball in various sources, including letters, diaries, newspapers, memoirs and regimental histories. These accounts indicate that northern troops played the sport more often than their Confederate counterparts, and that the sport garnered the most popularity among units from New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.

In addition soldier accounts reveal that they most frequently played baseball in the winter and spring months, with games peaking during the months of March and April. This served as an ideal time to play, as fair weather coincided with reduced army activity. Typically the active campaigning season for Civil War armies began at some point in May and lasted through November. The armies stayed in winter quarters during the months of December, January and February, and many roads became impassable in March and April due to heavy rains. During these months, soldiers sought to keep themselves occupied, and whenever the weather cooperated, they organized ballgames.

Reporting on camp life in the Army of the Potomac on Nov. 18, 1861, a correspondent for the Chicago Tribune related that “a song, a light-hearted laugh… a wrestling match, a foot race, or a party at base ball are the leading variations on the more formal duties.”

New Jersey veteran Camille Baquet recalled of camp life during these lulls: “Drill, dress parade, inspection, picket and guard duty, policing, [and] building roads were the usual occupations. Amusements were encouraged and chess, checkers, baseball and athletic exercises helped to while away tedious hours.”

The armies frequently held competitive games that attracted crowds of soldier-spectators and generated a great deal of interest in the camps. Often the ballplayers of one company, regiment or brigade would challenge the ballplayers from another. The rules for these games varied from regiment to regiment, and frequently the competing teams would have to iron out rule variations prior to the start of each match.

Some accounts tell of baseball games taking place between soldiers on both sides, though these stories – like most involving Union and Confederate fraternization – are difficult to prove and likely mythological, or at the very least exaggerated.

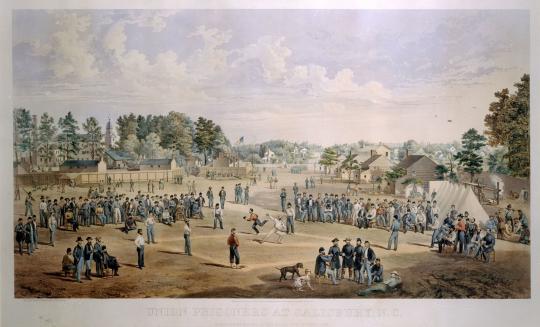

Baseball also served as a popular diversion for soldiers held in prison camps, particularly early in the war. Otto Boetticher, a soldier in the 68th New York, preserved for history one of the more famous depictions of baseball during the Civil War when he sketched Union soldiers playing ball at Salisbury Prison in North Carolina as he awaited exchange in 1862. Others imprisoned at Salisbury also left accounts of baseball there. A doctor named Charles Gray recorded in his diary that prisoners played ball nearly every day that the weather allowed.

Through 1863, the Union and Confederacy operated an exchange cartel that allowed man-for-man exchanges – keeping the number of imprisoned soldiers relatively low. In 1863, this system broke down as a result of Confederate refusals to treat black soldiers as prisoners of war. With no exchanges, prisons swelled to beyond capacity, and living conditions for those incarcerated – particularly in southern prisons – became abominable. Due to the resulting poor health of the soldiers and a lack of space, strenuous physical activities like baseball became very rare in prison camps during the latter part of the war.

Baseball during the war wasn’t limited to soldiers, however. Northern cities continued to teem with activity throughout the war, and baseball remained one of the prominent leisure time activities on the northern home front. By 1861, the sport had built a significant following in many cities. The most successful teams of the day attracted thousands of spectators to games, and newspapers provided accounts of all the latest contests. The start of the war understandably cast a shadow over the sport, and several clubs disbanded as players deemed it their patriotic duty to volunteer for the Union cause. Even the clubs that remained active reduced the length of their playing schedule in 1861.

Much like baseball in the 20th century, however, wartime could not halt the sport. Baseball continued, and indeed flourished in the north during the war, as many players did not volunteer and were not drafted. Ballgames featuring top competition continued to draw large crowds, and newspaper accounts of these matches appeared alongside reports from the front.

On June 7, 1862 for example – with the Union Army of the Potomac within a few miles of the Confederate capital – The New York Times reported on a match between a traveling team from Philadelphia and a team picked from some of Brooklyn’s best clubs, including the Atlantics and the Excelsiors. The Times thought that the crowd was “by far the largest assemblage which has gathered upon any base ball ground during this season.” In a game the previous day, the Philadelphia squad had played a team selected from the Eckford, Putnam and Constellation clubs – “organizations which are well known to fame for their first-class players.” The Times reported that spectators in the crowd included representatives from New York and Brooklyn clubs, as well as those from Philadelphia, Boston, Albany, Troy and many other locales.

The game itself continued to evolve during the war as well. The National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) – the first organized governing body for the sport founded in 1857 – continued to meet annually, though attendance at NABBP conventions dropped significantly. Those participating in these conventions frequently debated rule changes, and several important rules were altered during the war. In 1863 the NABBP altered several pitching regulations. In 1864, a new fly rule passed – a batter was no longer out if a fair ball was caught on one bounce, a fielder had to catch the ball on the fly (though the bounce rule remained for foul balls).

“They played baseball continually throughout the war,” Spencer points out, “there was something every week.”

Steve Light was the manager of museum programs at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum