- Home

- Our Stories

- World War II hero’s legacy lives on in Cooperstown

World War II hero’s legacy lives on in Cooperstown

In 1939, Harry O’Neill was living his dream of playing big league baseball with his hometown team. He even saw action in an exhibition game at Cooperstown’s Doubleday Field during that season. But not long after this young athlete’s life was ended prematurely, like thousands of others, in a global conflict halfway around the world.

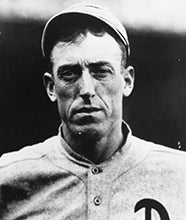

Though his major league playing career was brief, consisting of only a single game in 1939, O’Neill is best remembered today as one of only two major leaguers – along with Elmer Gedeon - who lost their lives during World War II.

Born in Philadelphia, O’Neill was a three-sport star at nearby Gettysburg College, excelling at baseball, football and basketball. In March 1939, he was named a co-winner of Gettysburg’s prestigious Charles W. Beachem athletic award, based on outstanding athletic ability, commendable scholarship and Christian character.

So it came as no surprise when it was announced that the three-year catcher for the Bullets, affectionately nicknamed “Porky,” had signed a professional playing contract with the Philadelphia Athletics on June 5, 1939, soon after his graduation exercises were complete. O’Neill’s baseball coach at Gettysburg was Ira Plank, brother of Hall of Famer and fellow Gettysburg alum Eddie Plank.

Instead of heading to the minors upon his deal with the A’s – a franchise in the midst of a nine-year stretch of losing at least 90 games per season – the 22-year-old O’Neill immediately joined the major league club as a third-string backstop, replacing Hal Wagner, who was shipped to the minors. O’Neill was now playing behind starter Frankie Hayes, who would be named to his first of six All-Star teams that year, and veteran backup Earle Brucker.

But playing time was scarce for the young O’Neill, who appeared in his first and only big league game on July 23, 1939. In a 16-3 drubbing at the hands of the host Tigers, O’Neill relieved Hayes, the starting catcher, in the eighth inning. His inauspicious major league debut, serving as the batterymate for reliever Chubby Dean, resulted in neither a plate appearance nor a fielding chance.

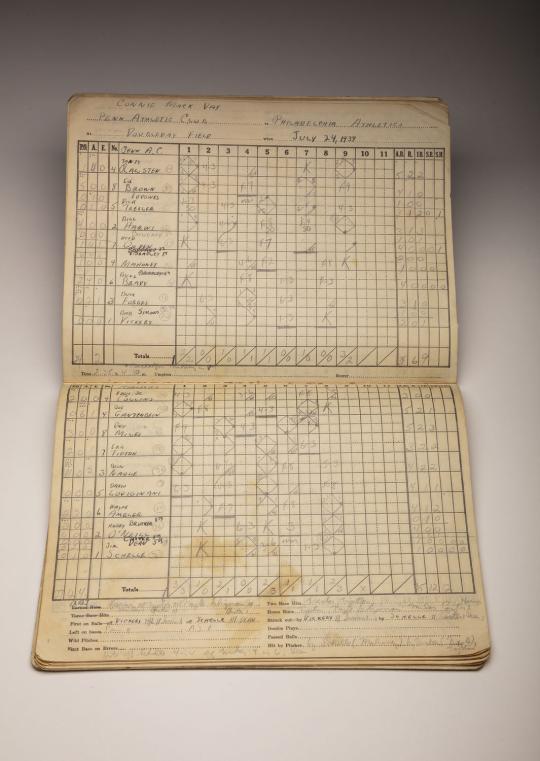

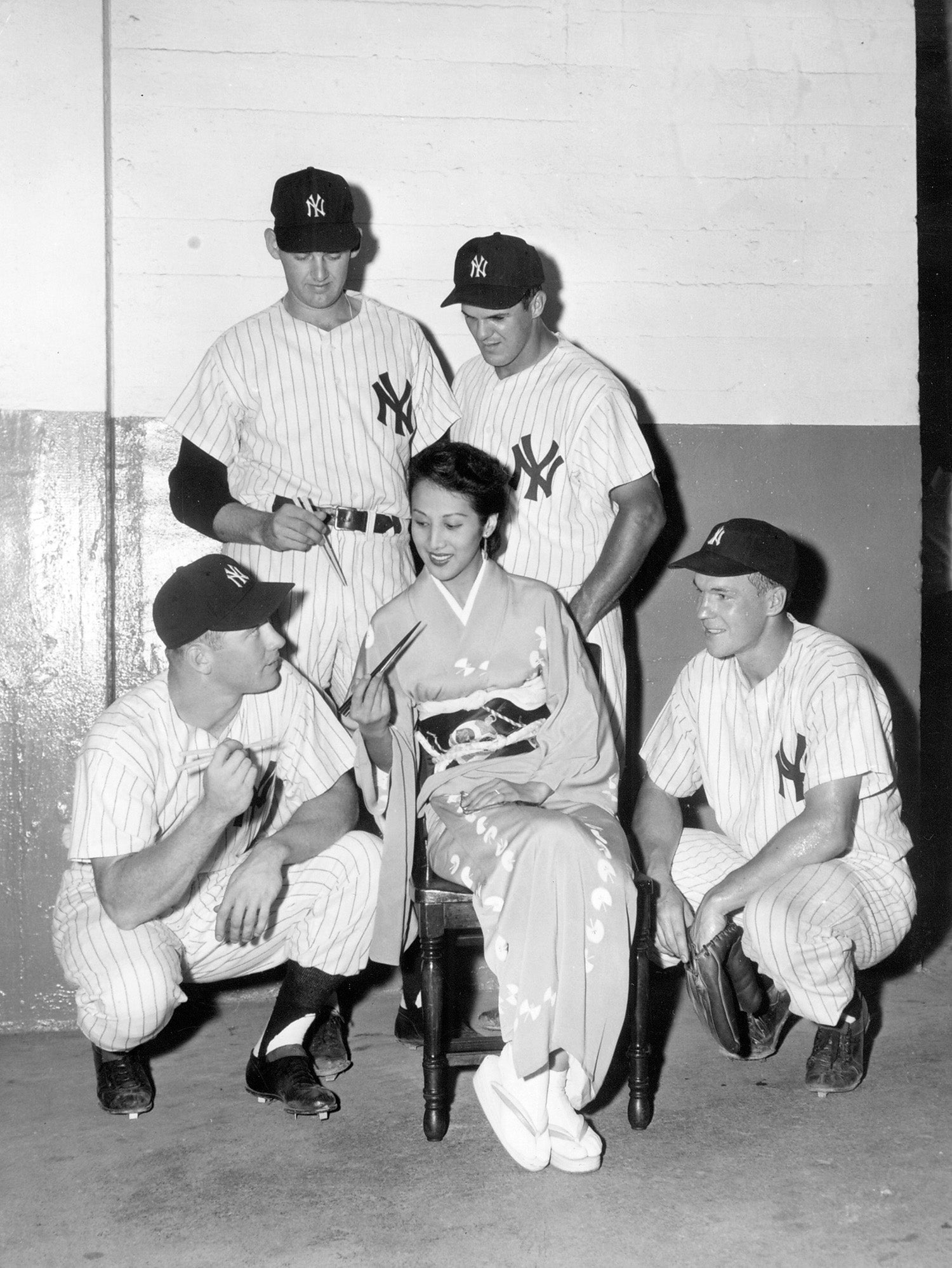

The next day, on July 24, O’Neill and his A’s teammates were in Cooperstown, N.Y., a part of a four-month celebration in the village honoring the game’s 100th anniversary. The highlight of that summer came on June 12 when the National Baseball Hall of Fame would hold its first Induction Ceremony.

From May through August that year, the area was abuzz with baseball, with the newly-christened Doubleday Field playing host to special high school, college and semi-pro contests.

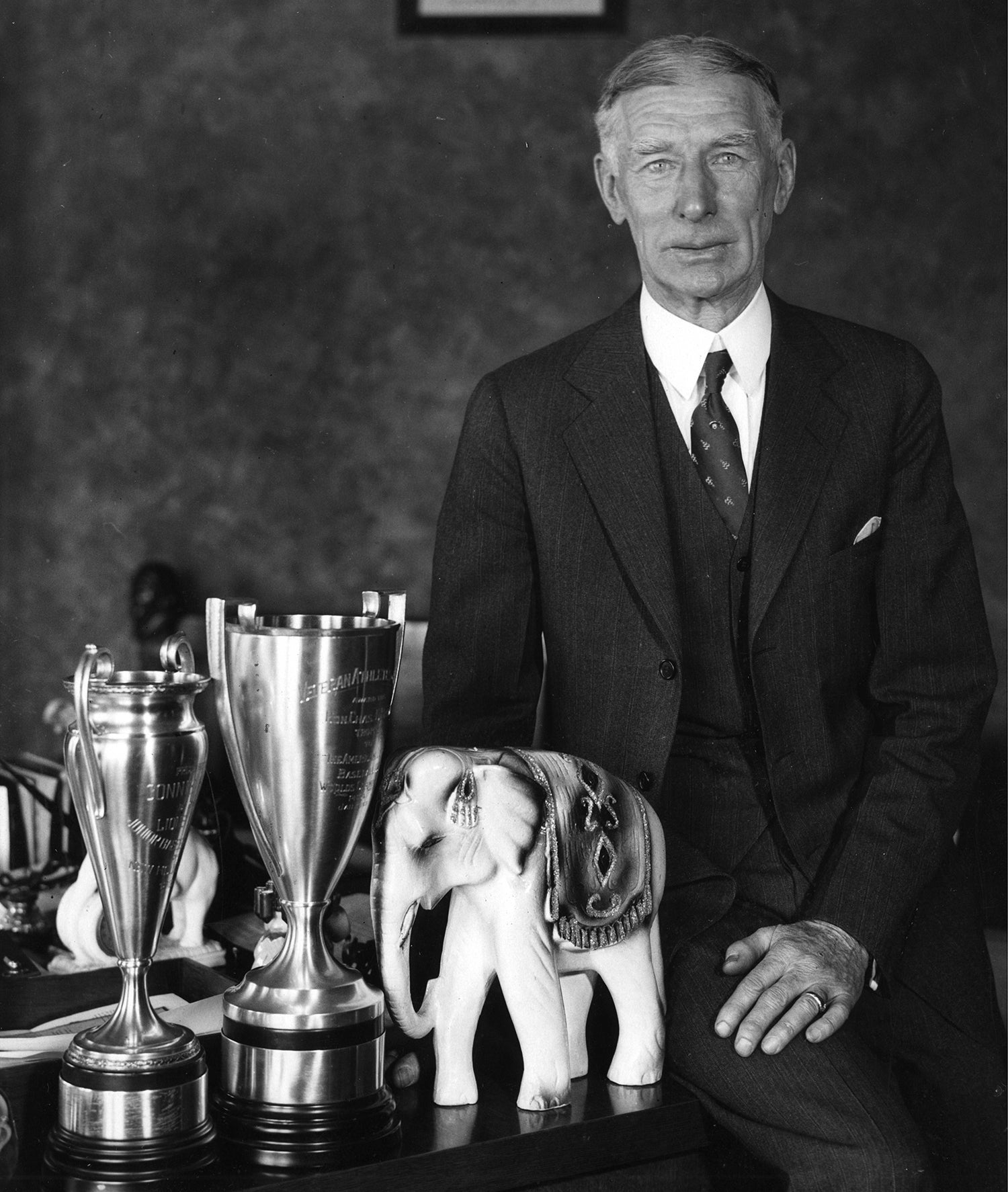

Among these litany of events was “Connie Mack Day,” a contest pitting the Athletics – the first major league team to play on Doubleday – against the Penn Athletic Club of Philadelphia. The exhibition, an annual event in Philadelphia, was moved to Cooperstown in 1939 because of the centennial celebration. But unfortunately for fans of the 76-year-old “grand old man” of the game, the guest of honor wasn’t able to attend due to illness.

O’Neill, who after much disuse inactivity was now seeing playing time for the second straight day – albeit in an exhibition – was the starting catcher and batting eighth in the lineup. Recent Yale University graduate Eddie Collins Jr., the son of the 1939 Hall of Fame inductee, was also in the starting lineup in right field for the A’s.

In the Athletics’ 12-6 triumph on this swelteringly hot afternoon before an estimated 2,500 fans, with Pennsylvania Governor Arthur H. James the guest of honor, the big leaguers clubbed five home runs, including a memorable one by Bill Nagle that cleared the leftfield bleachers and landed in a tomato patch. O’Neill was 0-for-4 at the plate with four putouts and a passed ball in the nine-inning affair that took two hours and 15 minutes.

According to The Otsego Farmer, a local Cooperstown weekly newspaper, O’Neill played a small part in a noteworthy event: “During the fourth inning, a foul ball hit by O’Neill of the A’s came over the net into the stand and hit little Robert Stanley Johnson on the head. A boy in front of the lad got the ball but quickly gave it to ‘Bobby.’ Our hat is off to the boy who caught the ball and gave it to the boy who was hit.”

For O’Neill, these few appearances most likely proved to be the highlights of his professional playing days. Released by the Athletics in September 1939, his career ended with a 16-game stint serving as a backup catcher with the Pittsburgh Pirates-affiliated Harrisburg (Pa.) Senators of the Class B Interstate League in 1940.

O’Neill’s story echoed that of Archibald "Moonlight" Graham, the real-life ballplayer who played only an inning for the 1905 New York Giants before his story was immortalized in the 1982 book “Shoeless Joe” and the 1989 film Field of Dreams.

During the summer of 1939, while O’Neill was still on the roster of the A’s, it was reported that the Darby (Pa.) High School grad was named head football coach and assistant basketball and baseball coach at Upper Darby Junior High School. And this was where he remained until America’s involvement in World War II.

In September 1942, O’Neill had enlisted in the Marine Corps and entered Marine Officers’ Training School, trading in his familiar baseball togs for a military uniform. Lieutenant O’Neill would later receive the Purple Heart as the result of a 1944 shrapnel wound in Japan. After returning to duty, the former big league baseball player received a fatal injury on March 6, 1945 in Iwo Jima, Japan, at the age of 27. It wasn’t until April that O’Neill’s wife Ethel received from the War Department killed in action.

In a heartfelt 1945 letter currently stored at Gettysburg College, O’Neill’s mother replies to her son’s college football coach extending condolences.

“We are trying to keep our courage up, as Harry would want us to do, but our hearts are very sad and as the days go on it seems to be getting worse,” she wrote.

“Harry was always so full of life, that it seems hard to think he is gone. But God knows best and perhaps someday, we will understand why all this sacrifice of so many fine young men.”

The remains of O’Neill, initially buried in Iwo Jima, were later brought to Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pa., in 1947.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum