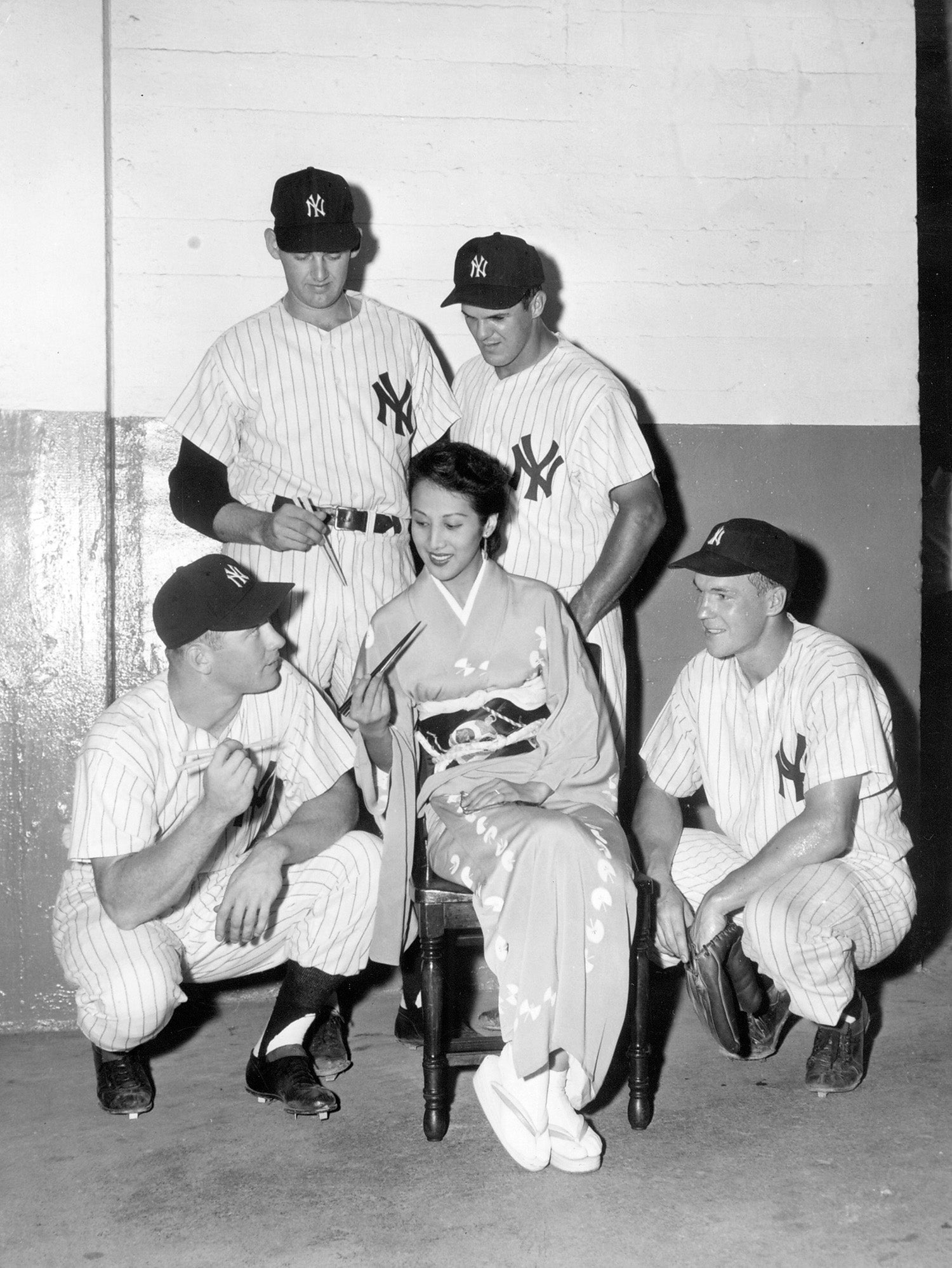

I once told a newspaper reporter that the bombing attack we lived through on the Alabama had been the most exciting 13 hours of my life. After that, I said, the pinstriped perils of Yankee Stadium seemed trivial. That’s still true today.

- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Reflections on World War II

#GoingDeep: Reflections on World War II

On the afternoon of Dec. 7, 1941, 23-year-old Bob Feller was driving east on Route 6, near the Iowa-Illinois border. He was in his new Buick Century, heading to Chicago to meet Indians scout Cy Slapnicka and manager Roger Peckinpaugh. Coming off of a 1941 season which included a league-leading 25 wins and a $5,000 raise from the year before, Feller decided he could splurge on something he’d been eyeing for a while: A radio. But as he began crossing the Rock Island Centennial Bridge into Illinois, he was more focused on his impending meeting than on the station he was listening to.

That was about to change drastically.

His program was interrupted by an emergency bulletin, announcing that the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Imperial Japanese Navy. The United States was about to enter World War II.

“Like everyone else alive that afternoon, my life changed drastically in that one shock,” Feller recalled in his autobiography Now Pitching, Bob Feller. “As I drove on, fighting to keep my mind on the road, I knew that the purpose of our meeting had just changed. Now I had to tell Slap and Peck that I was going to enlist in the Navy immediately.”

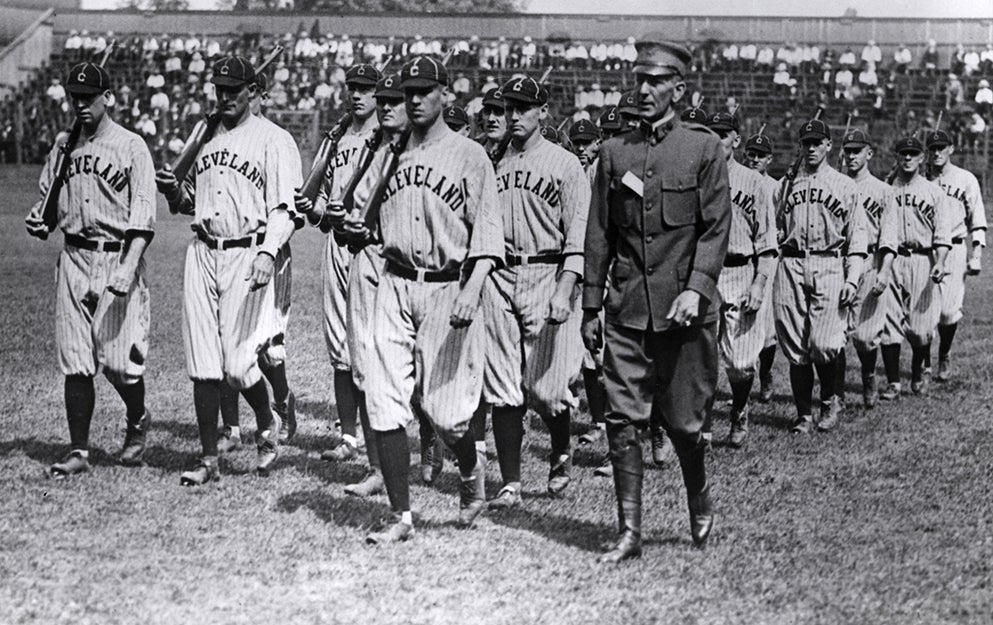

As the world observes the anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, millions of Americans are reflecting on the harrowing time, among them the surviving heroes of the estimated 1,400 major league players, umpires, managers and coaches who served in the Armed Forces in World War II. Feller was one of the first to enlist, leaving a professional baseball career on the rise to serve his country for nearly four years, in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters. But looking back on it in 1989, Feller had no regrets.

“When I think about the military service, those years missed, at least they were serving their country which is just as important if not more so than the baseball stats,” Feller said. “I’d imagine that winning a war is much more important than winning a ballgame.”

“Rapid” Robert, who was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, was about as dogged on the battlefield as he was on the mound. Refusing to accept his 3-C deferment status due to his father’s terminal illness, he threw himself into the action, eager to play an active role in the war effort. But due to his fame as a pitcher, he was initially assigned to help Gene Tunney run the Navy’s physical fitness program in Norfolk, Va.

“Helping Tunney in his program was fine, but it didn’t take me long to know I wanted more action than that,” Feller said in Now Pitching. “I volunteered for gunnery school, and the Navy apparently took my desire for action seriously. Following six months of training, I was made chief of an anti-aircraft gun crew of 24 men on the USS Alabama.”

During his time in the Navy, Feller endured everything from hurricanes with winds of 180 MPH to enemy bombs fired at his ship to impending kamikaze attacks. The Alabama participated in some of the Pacific theater’s most violent battles. Discharged as a Chief Petty Officer in 1945, Feller would receive five campaign ribbons and eight battle stars for his service. To the dismay of opposing hitters all over the league, he didn’t waste any time picking up where he had left off on the diamond.

“Nine days after the Japanese had surrendered and a week before the documents were actually signed, I was on the mound in Cleveland,” he said in an interview with Todd Anton, published in No Greater Love: Life Stories from the Men Who Saved Baseball. “It was Friday, Aug. 24, 1945. I struck out 12 and gave up just four hits in a 4-2 win over Detroit’s Hal Newhouser.”

But one of things that made World War II – particularly the impact of the attack on Pearl Harbor – so unique, was the degree to which it affected citizens nationwide. Hundreds of miles away, while Feller was still in Norfolk, future major league umpire Augie Donatelli was working in the coal mines of Western Pennsylvania when he heard the news.

“I worked outside as a coal dumper, and I worked inside as a loader, worked on the motors inside, and that was all there was to it,” said Donatelli in an interview conducted by Larry Gerlach. “I was still loading coal when the war broke out. I enlisted, but I was right near being drafted. I became a tail gunner in the Air Force.”

While Donatelli and Feller both had similar responses to the attack, they had drastically different journeys in the military. Unlike “Rapid” Robert, Donatelli had been bouncing around the minor leagues prior to the war, and couldn’t seem to catch a break in the big leagues.

“I was sent to the Penn State league,” Donatelli said. “It was local, you might say. Two times I was in the league, and then the league folded in 1938. I signed with the St. Louis Browns. Pat Monahan scouted me. After that league folded I went back to work in the mines.”

As fate would have it, Donatelli’s baseball career would be impacted by his time serving overseas. Initially recruited for the baseball team at Lowry Air Force Base while he was attending technical school, he would only stay there for a couple of years, as he went into combat in 1943.

Trained as a B-17 tail gunner, Donatelli would complete 17 missions before being shot down over Nazi Germany in March of 1944, on a daylight raid in Berlin. Surprisingly, his umpiring career would start in the German Prisoner of War camp Stalag Luft VI.

“In the prison camp there, they didn’t have any baseballs, but they did have some softballs,” Donatelli explained in his interview with Gerlach. “When we started combat over there, the English were prisoners of war there, and the Germans put the Americans with them. The camps were getting big. When I had jumped out of the plane, I had busted my ankle, so I couldn’t play.”

“They couldn’t find any umpires they were pleased with. That knew the rules, the judgement calls. I used to sit along the sidelines and watch them [without an umpire] and laughed – you had to have an umpire. So when you’re behind the plate, and they found out you can umpire, your whole compound would come after you to come umpire for them. So, I started umpiring that way. It didn’t strike me that I should umpire, but I wanted to see that the rules were run right. But then I came back here and started umpiring because I felt I could umpire.”

After years of feeling as if he hadn’t met the big league standard, Donatelli had finally found his ticket to the major leagues. In his interview, his pride is almost palpable when he describes his rapid journey from a makeshift umpire in World War II to a professional one in just under five years after he came home from war.

“I went down to [Bill McGowan’s] Umpire School that winter in Cocoa Beach, Fla. I never thought I would get a job,” said Donatelli. “There were 100 guys at the school – big guys, small guys, old guys – and most of them were umpires, four or five of them already had professional contracts.”

“McGowan came to the school and watched the students,” Donatelli continued. “You worshipped a guy like that, that was in the majors. One day he said, ‘We have a fella in here who’s going to be in the major leagues in three years.’ He pointed at me, and I thought ‘This guy couldn’t mean me.’

Everyone turned around to look, and he said ‘Yes you. We feel you’re going to be in the majors in three years.’”

After brief stints in the Pioneer League, South Atlantic League and International League, Donatelli finally arrived at the National League in 1950. He would serve as an umpire for 24 years, calling five World Series and four All-Star games, founding the Major League Umpires Association and even gracing the inaugural cover of Sports Illustrated in 1954 (while calling a Milwaukee Braves game behind home plate).

His fiery on-field demeanor should have come as no surprise, when sized up against the adversities he faced during his time at Stalag Luft VI.

“There was no food, no clothes, it was cold in the winter,” Donatelli said. “It was just struggling, waiting. You just waited for your next meal. They started sending us Red Cross parcels, but after about six months we started sharing the food boxes. We would get one for four men once a week.”

“We changed camp three times, and walked all over Germany for three months in the winter. We went from Frankfurt to Heidekrug, and then took a ship to Kiefheide. Once we got to Kiefheide, they took us off of the ship and chained every one of us. There was a three mile run [to reach the camp], they chased us all the way up there. Guards were hitting us with bayonets.”

Some of the lessons Donatelli learned on the battlefield were applied throughout the duration of his umpiring career. He picked up qualities like decisiveness and a firm backbone, which were also important in keeping a game running smoothly.

“It takes superhuman judgment – all you’ve got at times – to call a play,” said Donatelli. “There are some things you can’t control, we have some players in the game today that you can’t control other than throwing them out of the game. If they argue with you, show you up, you’ve got to throw them out. Good judgement, get the respect. You’ve got to be a leader.”

For Bob Feller, his four years overseas put the challenges he faced on the field in perspective.

“It makes a difference when you go through a war, no matter which branch of service you’re in,” Feller said in an interview with the U.S. Naval Institute. “A war teaches you that baseball is only a game, after all – a minor thing, compared to the sovereignty and security of the United States. I once told a newspaper reporter that the bombing attack we lived through on the Alabama had been the most exciting 13 hours of my life. After that, I said, the pinstriped perils of Yankee Stadium seemed trivial. That’s still true today.

“I believe I gained much more than I lost from my military service,” said Feller in No Greater Love. “There are probably some records I could have had, like no-hitters, wins or strikeouts. But I have no regrets. We served our flag and our country without question and with honor. It is all about winning. Whether it’s on the ballfield or the battlefield. We’re Americans. We always play to win.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame