“[Jerry Grote is the] toughest catcher in the league to steal on.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1971 Topps Jerry Grote

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Jerry Grote

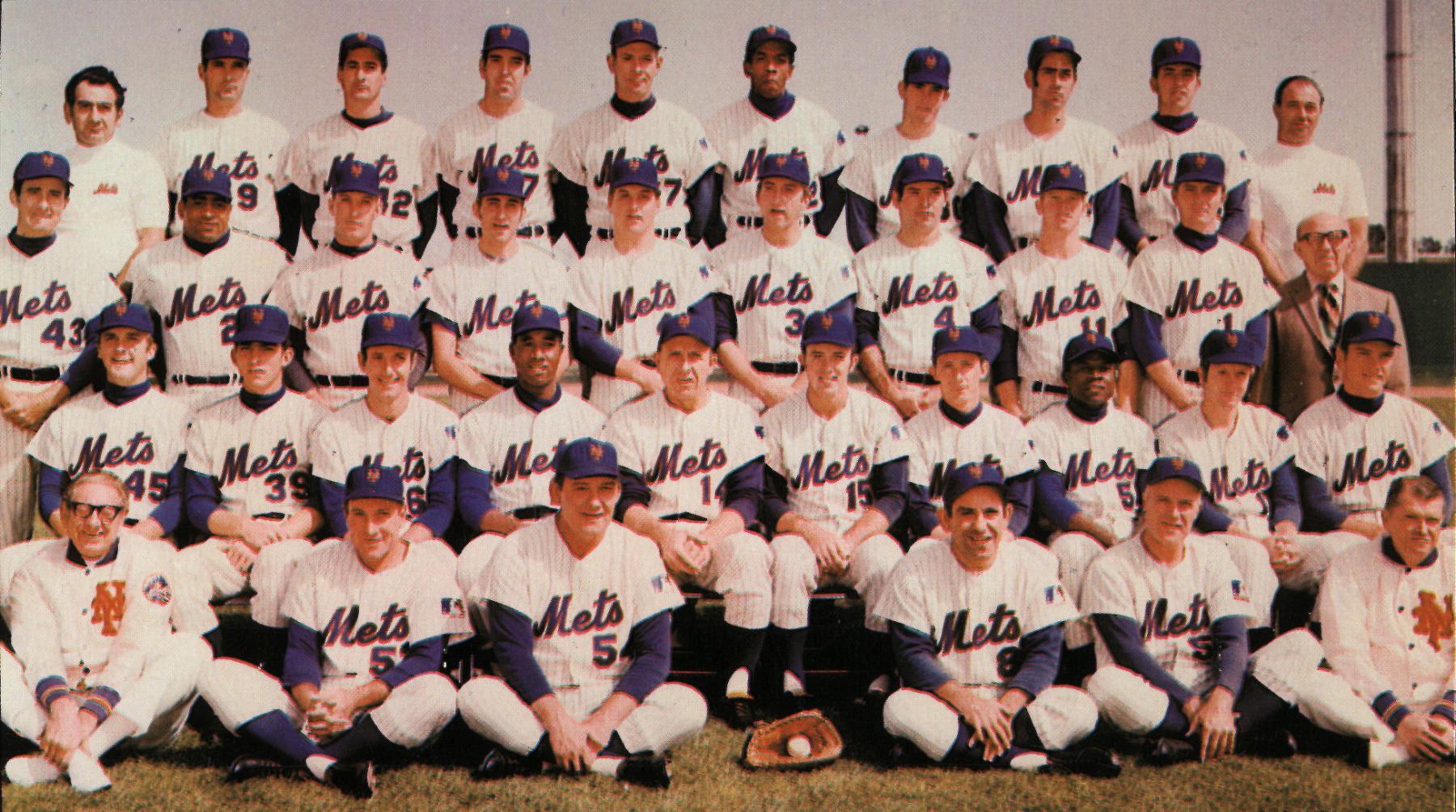

With the New York Mets back in the World Series for the first time since 2000, I inevitably find myself thinking about the first time that the Mets ever ventured into the territory of autumn glory. Those Mets of 1969 pulled off one of the top five upsets in the history of the World Series, defeating a Baltimore Orioles team that had the overwhelming talent of a dynasty.

In thinking about those Mets of ’69, the epic efforts of Hall of Famers Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan in the postseason come to mind, as do the home run heroics of midseason acquisition Donn Clendenon and the game-saving World Series catch by an atypically acrobatic Ron Swoboda. It was all beautifully orchestrated by the imposing Gil Hodges, a manager who was both loved and respected, perhaps in equal amounts, by his overachieving band of players.

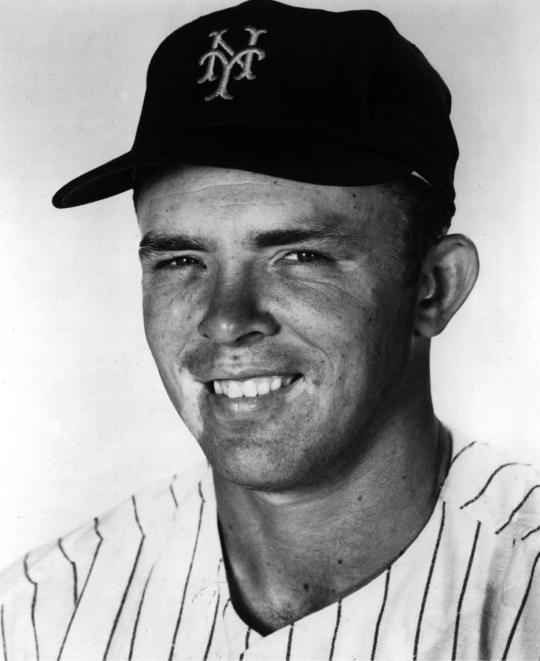

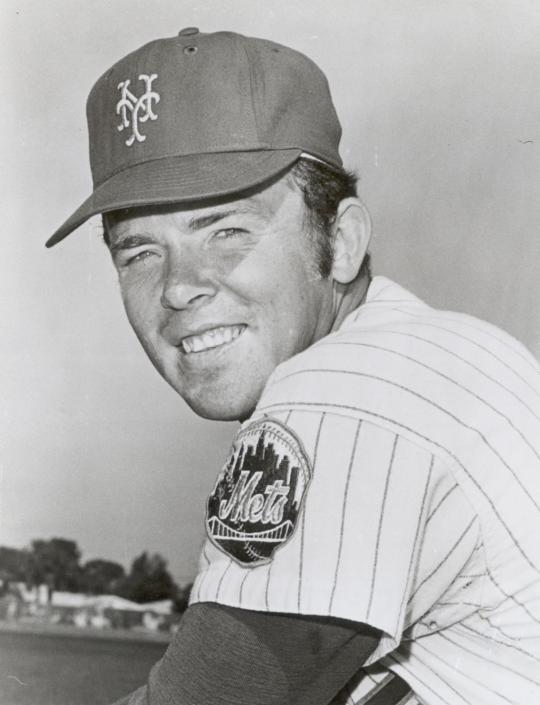

There is a tendency, however, to forget about the contributions of some of the 1969 Mets, some of whom were role players and some who remain downright obscure. Perhaps at the top of the former list is an old-school catcher named Jerry Grote, who will never be confused with Gary Carter, Mike Piazza, or even Todd Hundley when it comes to hitting a baseball. But in the more nuanced and subtle areas of defense and baserunning, the toughened Grote was just as responsible as the more famous Mets for making world champions out of a recent also-ran.

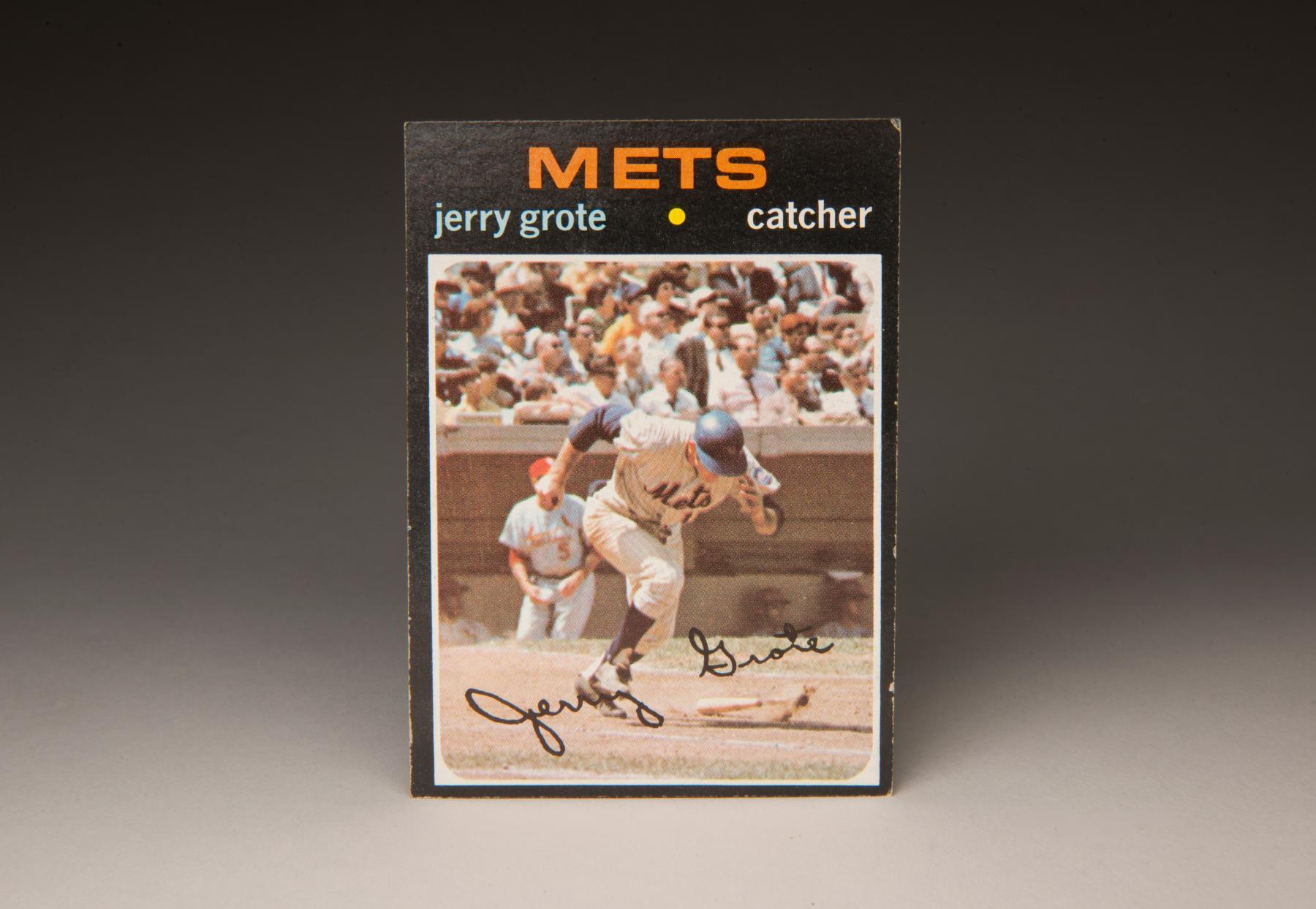

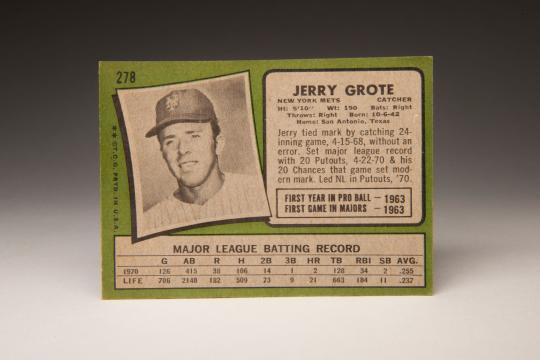

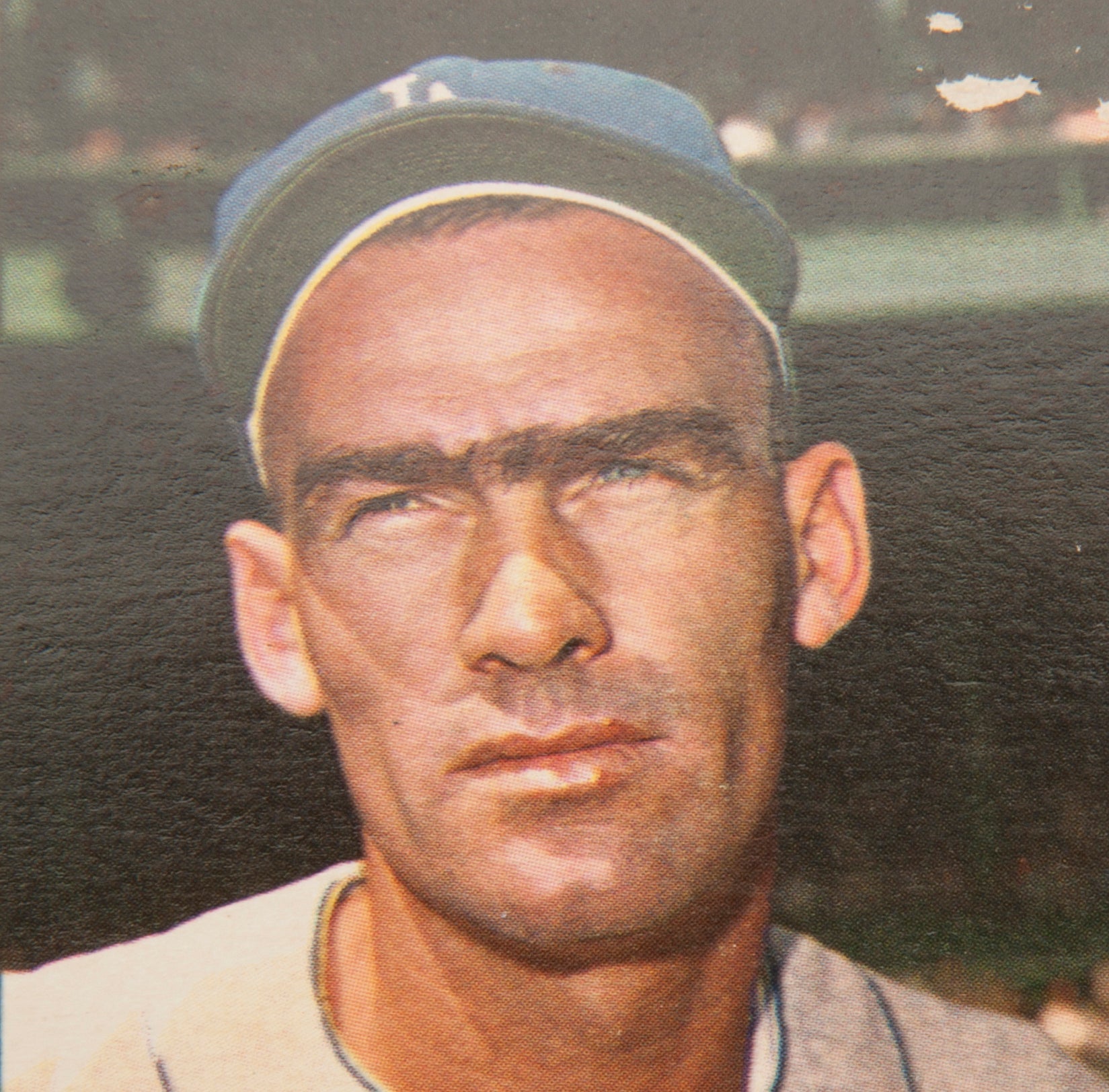

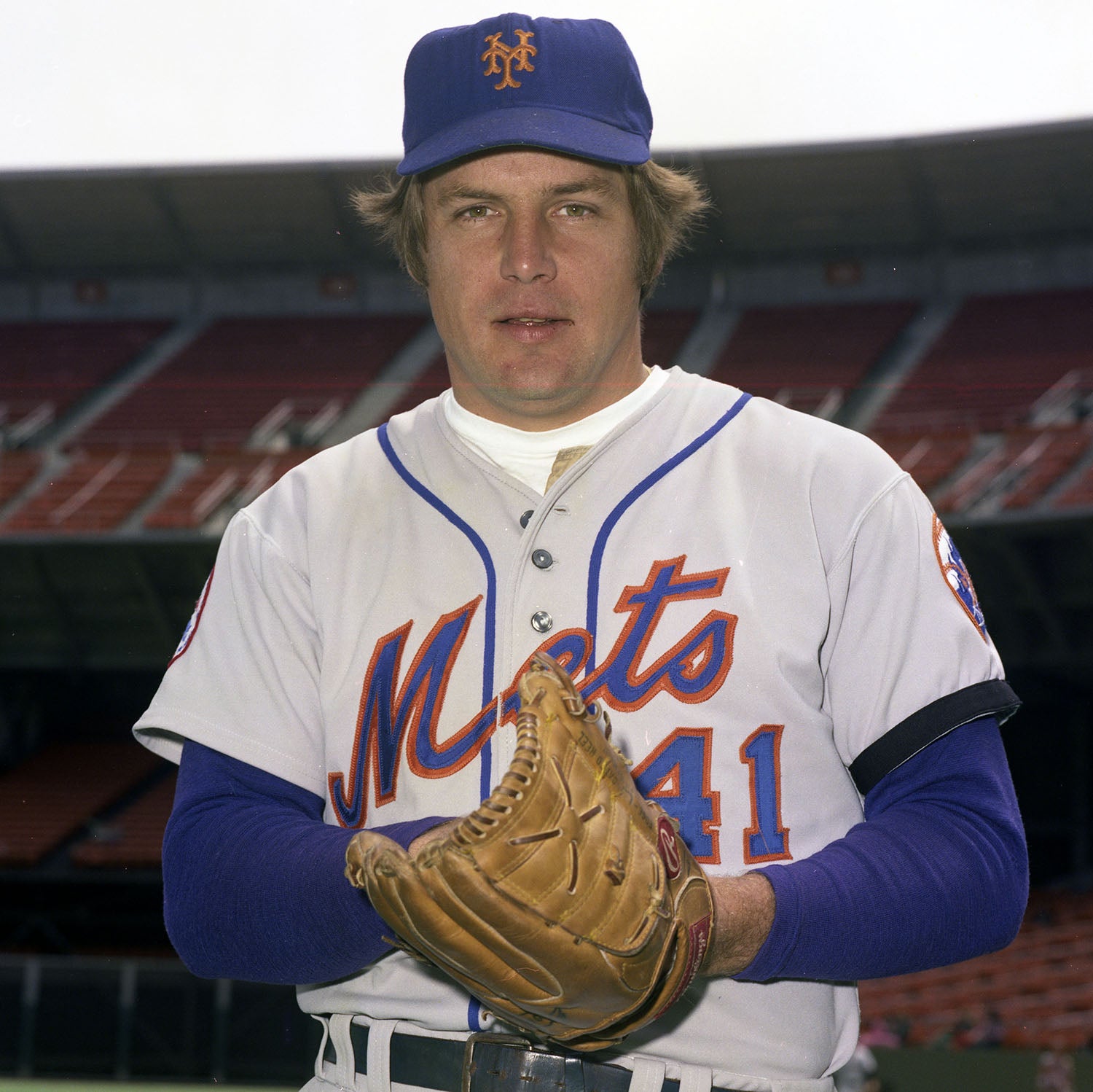

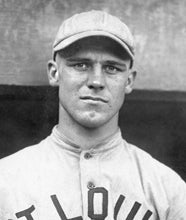

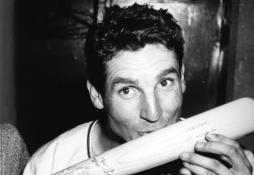

Of all the baseball cards that Topps has ever produced, none epitomizes the player on it more than Jerry Grote’s 1971 card. This was the first year that Topps used live game action on its cards -- and none of the action shots are any better than the Grote image. We see him playing in a game, almost certainly during the 1970 season, at Shea Stadium. Grote and the Mets are taking on the St. Louis Cardinals, as evidenced by the presence of Redbirds personnel in the third base dugout. (That is veteran coach Dick Sisler, the son of Hall of Famer George Sisler, wearing No. 5 in the background.)

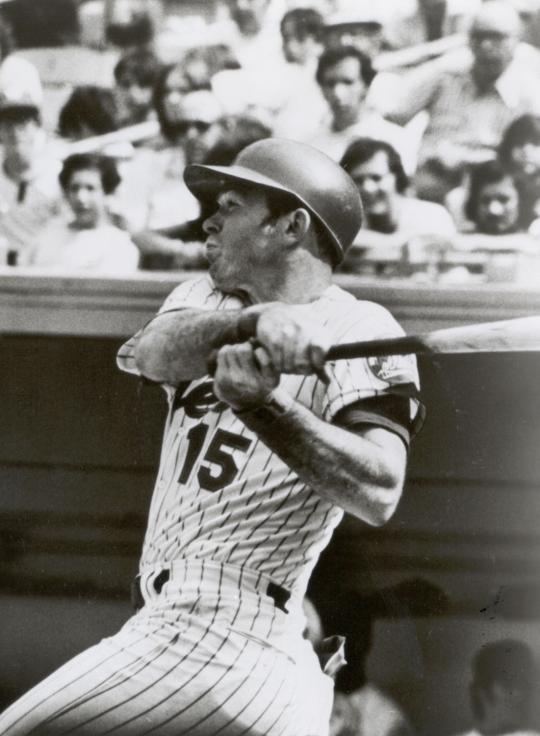

Moments after making contact with a pitch from an unknown Cardinals pitcher, we see Grote busting his way out of the right-handed batter’s box. His head down, his arms pumping furiously, Grote is running as though this were Game 7 of the World Series, not a midsummer game lost to time and memory.

Grote did not believe in bat flips, or fist pumps, or jogging to first base on a tapper back to the mound. For a player like Grote, the way that we see him running on this Topps card was the preferred way to run out the ball, whether it was a ground ball single, a pop-up on the infield, or a long fly ball to the warning track. In Grote’s mind, it was not just the right way to play the game; it was the only way to do so.

Grote might not have fit in with today’s game, which is filled with more showmanship than the era that predated free agency. Just as Grote did not like to pose in the batter’s box, he also did not like to fraternize with the opposition. He did not enjoy talking to the media, either before or after the game. He just wanted to play the game that day, play it hard, and win as often as possible. Those were attributes that would help the Mets, never more so than in 1969, and then again in 1973, when they surprised the baseball establishment by winning the National League pennant.

We tend to think of Grote as a lifelong member of the Mets, but it’s not true. It’s easy to forget that he started his career in the organization of the Houston Colt .45s. Grote made his major league debut with Houston in September of 1963, when he entered a game in the late innings as a defensive caddy for starting receiver John Bateman. On Sept. 27, Grote became a part of a most unusual development, as the Colt .45s started the first all-rookie lineup in major league history. That lineup featured three future stars in Rusty Staub, Joe Morgan and Jimmy Wynn.

In contrast to those three youthful talents, Grote would struggle with the Colt .45s. Yet, it wasn’t because he lacked commitment or effort. In fact, Grote built his own batting cage at his parents’ home in San Antonio. He constructed the cage out of chicken wire and old carpeting, and spent hours during the winter taking practice swings against an “Iron Mike” pitching machine.

As much work as Grote put in, he continued to flail against live pitching, hitting .181 with a .240 on-base percentage and little power for Houston (by now renamed the Astros). By the end of the 1965 season, the Astros gave up on the light-hitting Grote and traded him to the Mets for a pitcher named Tom Parsons.

The trade was one of the best that Hall of Famer George Weiss engineered as general manager of the Mets. Wisely, Weiss listened to the advice of one of his top scouts, Red Murff, who had originally signed Grote while working for the Houston franchise.

With Grote in place as the starting catcher for the 1966 season, the Mets avoided the 100-loss mark for the first time in their young franchise history. Grote’s competitiveness impressed his teammates, some of whom began to play the game with more determination. Given his toughness and stellar defense behind the plate, the Mets didn’t care that Grote hit only .237 with a mere three home runs.

Grote sometimes took that competitiveness to extremes. As just one example, he developed an interesting habit behind the plate. When a Mets pitcher recorded the third out of an inning on a strikeout, Grote tossed the ball to the side of the mound that was opposite from the other team’s dugout. He did that to make the enemy pitcher have to walk a little bit longer before bending over to pick up the ball. It might have seemed insignificant, but in Grote’s mind, it was worth doing just to make the opposing pitcher exert more effort.

Not only did Grote have little love for the opposition, he could be ill-tempered with teammates. That attitude carried over to his dealings with the media. He did not have much patience for questions from writers; he viewed them as outsiders who intruded on the sanctity of the clubhouse. And then there was his antagonistic relationship with umpires, which reached a low point during the 1967 season. Mets manager Wes Westrum faced a shortage of players -- only 21 healthy bodies -- for a midseason game against the Los Angeles Dodgers. After entering the game as a pinch-runner in the top of the seventh, Grote took his place behind the plate. Almost immediately, Grote began to complain about the strike zone being called by home plate umpire Bill Jackowski. At the end of the inning, Grote prolonged his diatribe, shouting at Jackowski from the dugout and then throwing a towel onto the field.

Jackowski had no choice but to eject Grote. That created a major problem for Westrum, who was now out of healthy catchers. Out of desperation, Westrum pressed outfielder Tommie Reynolds into service as his emergency catcher.

Not only did Westrum fine Grote for his actions, but general manager Bing Devine sought out Grote after the game and chewed him out for his indiscretion. Grote learned a valuable lesson: He had to curb his temper for the betterment of the team.

By 1968, Grote had revised his attitude toward umpires. “I made up mind that I wasn’t going to argue, no matter what,” he told Dick Young of the New York Daily News. “They’re really not bad guys.”

A wiser player after the lectures from Devine and Westrum, Grote still wanted to improve his profile as a hitter. He hit above .300 over the first half of 1968, earning selection as the starting catcher in the All-Star Game. He became only the second Met in history to earn a starting place on the National League All-Star team, joining second baseman Ron Hunt in a selective group. Grote would finish the season at a solid .282, but instead of taking kudos for the improvement, he credited new manager Hodges with helping him shorten his stride and quicken his swing.

While Grote was complimenting his manager, Hodges was recognizing Grote’s toughness. A classic example took place in September of 1969, as Grote played both games of a doubleheader against the expansion Montreal Expos. He totaled 21 innings in the two games, an unusual amount of work given the extreme demands of catching.

Hodges felt it was important for Grote to catch the young and talented Mets staff as often as possible. Even though Grote’s batting average fell off by 30 points in 1969, he improved his handling of the pitching staff, impressing Hodges greatly. His defensive play also reached a career peak. He committed only four passed balls and threw out 40 of 71 opposing base runners, accounting for a stunning success rate of 56 percent. In a sport where the better base stealers are successful 80 percent of the time, Grote’s numbers defied logic.

With Grote extracting the most of a youthful pitching staff, the Mets rallied to overtake the Chicago Cubs and win the National League East. Grote delivered key hits in Game 2 and Game 4 of the World Series, with both blows setting up important rallies. Grote played a subtle role in the Mets’ unexpected world championship.

Grote remained the Mets’ starting catcher through the next two seasons; the 1971 campaign was highlighted by his appearance on the cover of Sports Illustrated. That same year, Hall of Famer Lou Brock of the St. Louis Cardinals paid Grote the ultimate compliment, referring to him in the Sporting News as the “toughest catcher in the league to steal on.”

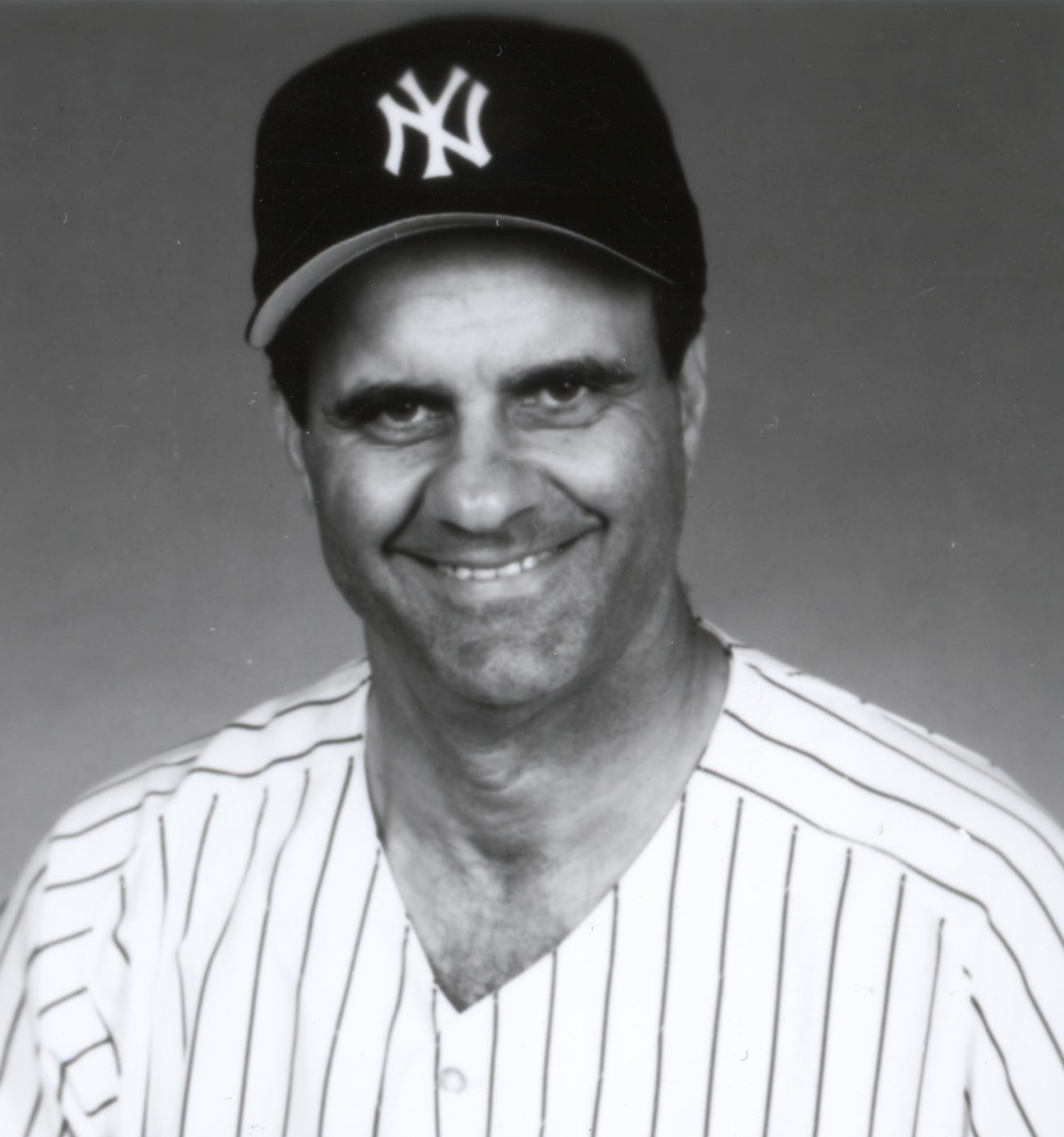

Then came the tragedy that affected all of the Mets in 1972: The unexpected death of the beloved Hodges during Spring Training. Shortly after Yogi Berra assumed command as manager, he demoted Grote to a backup role and made Duffy Dyer the No. 1 catcher. Some Mets observers speculated that Berra preferred Dyer because he hit with more power than Grote, but the new manager was actually protecting his veteran catcher. Grote was struggling with several bone chips in his throwing elbow, a condition that would require surgery in September.

The following spring, Grote returned to his role as starting catcher, but an errant fastball from Pittsburgh reliever Ramon Hernandez broke a bone in his right forearm and sidelined him for two months. Once again, Grote had to work his way back, eventually lifting his average from the .170s to the .250s. Grote and the Mets made a return to the postseason and eventually the World Series, before losing to the powerhouse Oakland A’s in seven games. As he did in 1969, Grote caught every inning of the 1973 postseason.

In 1974, Grote earned selection to his second All-Star Game, but he continued to suffer injuries that summer and ended up splitting time with Dyer. With the Mets increasingly concerned about the wear and tear on Grote’s body, they brought six catchers to Spring Training in 1975. Dyer was now out of the picture, having been traded to Pittsburgh, but veteran Jerry Moses and impressive rookie John Stearns had arrived to crowd the catching situation.

Just when Grote appeared to be losing his grip on the catching gear, he beat back the competition. The Mets sold Moses to the Padres, ensuring a place for Grote in the catching rotation. Playing through back problems, Grote batted .295, led all National League catchers in fielding percentage, and picked off six baserunners.

It was not until 1977 that Grote fell into a lesser role. Manager Joe Frazier made Stearns his starting catcher and began to use Grote occasionally at third base. That situation ended in late May, when Joe Torre came on as player/manager. Torre decided to move Lenny Randle from second base to third base and reinstate Grote as his backup catcher, behind the promising Stearns.

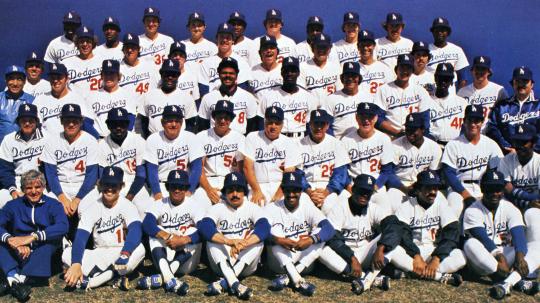

The 1977 season represented a year of massive turnover for the Mets’ franchise. At the June 15 trading deadline, the Mets began tearing apart the team by trading Seaver and Dave Kingman in a pair of deals. The firesale continued in late August, when the Mets sent the 35-year-old Grote to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Grote became the backup to Steve Yeager for the rest of 1977 and all of ‘78.

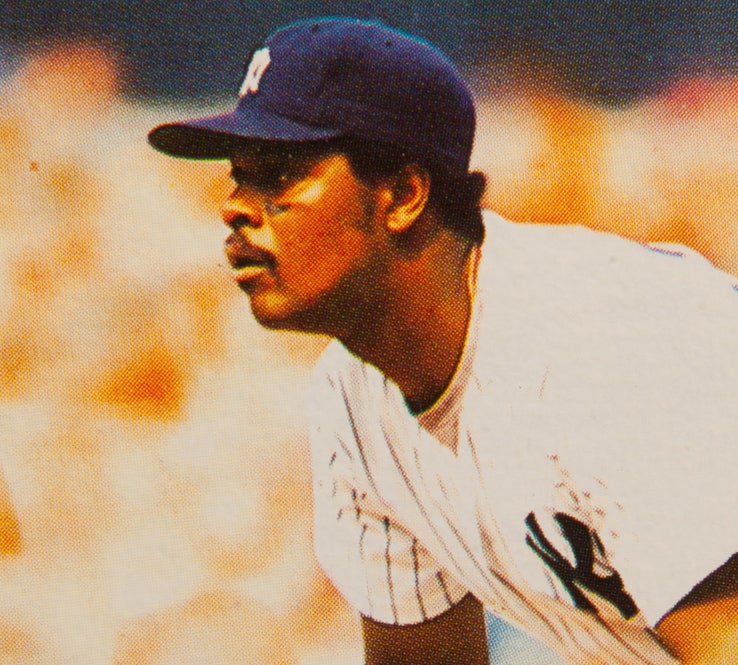

After the latter season, Grote became a free agent. He received a surprising inquiry from New York Yankees president Al Rosen, who offered Grote a two-year contract. Rosen explained to Grote that he would likely play no more than 40 games a season as a backup to All-Star catcher Thurman Munson. Grote considered the offer, but he was also struggling with family issues at the time. With family rating above baseball, he decided to retire.

The retirement lasted only two seasons. Grote decided to return to action in 1981, this time with the Kansas City Royals (giving him a connection to the Mets’ opponent in the 2015 World Series). Now mellower than in his high-intensity days with the Mets, Grote settled for a role as a third-string catcher behind John Wathan and Jamie Quirk. He enjoyed one last hurrah on July 3, when he set a Royals record with seven RBIs in a game against the Seattle Mariners. Grote eventually raised his season average to .304, but was surprisingly released on Sept. 1. Seven days later, he signed with the Dodgers, played in two games to finish out the season, and then decided to retire that winter.

With his baseball smarts and toughness off the charts, it was a natural for Grote to turn to managing. In 1985, Grote was serving as the manager of the Birmingham Barons, the Detroit Tigers’ affiliate in the Double-A Southern League, when he suddenly ran out of healthy catchers in the midst of a doubleheader. In between games, Grote phoned his general manager and asked him for permission to be activated for the nightcap. The GM said yes, so the 42-year-old Grote strapped on his chest protector, his shin guards, and his face mask, and gave catching one last whirl. Remarkably, Grote played an errorless and mistake-free game behind the plate. He also drew a walk and skillfully laid down a sacrifice bunt, making quite an impression on his youthful “teammates.”

Even in his 40s, some four years removed from his last days as a major leaguer, Grote had retained the same determination that he showed on his 1971 Topps card. For an old-school gamer like Jerry Grote, who passed away on April 7, 2024, when it came to being a professional and playing the game all-out, nothing had changed.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame