- Home

- Our Stories

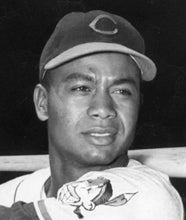

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Mudcat Grant

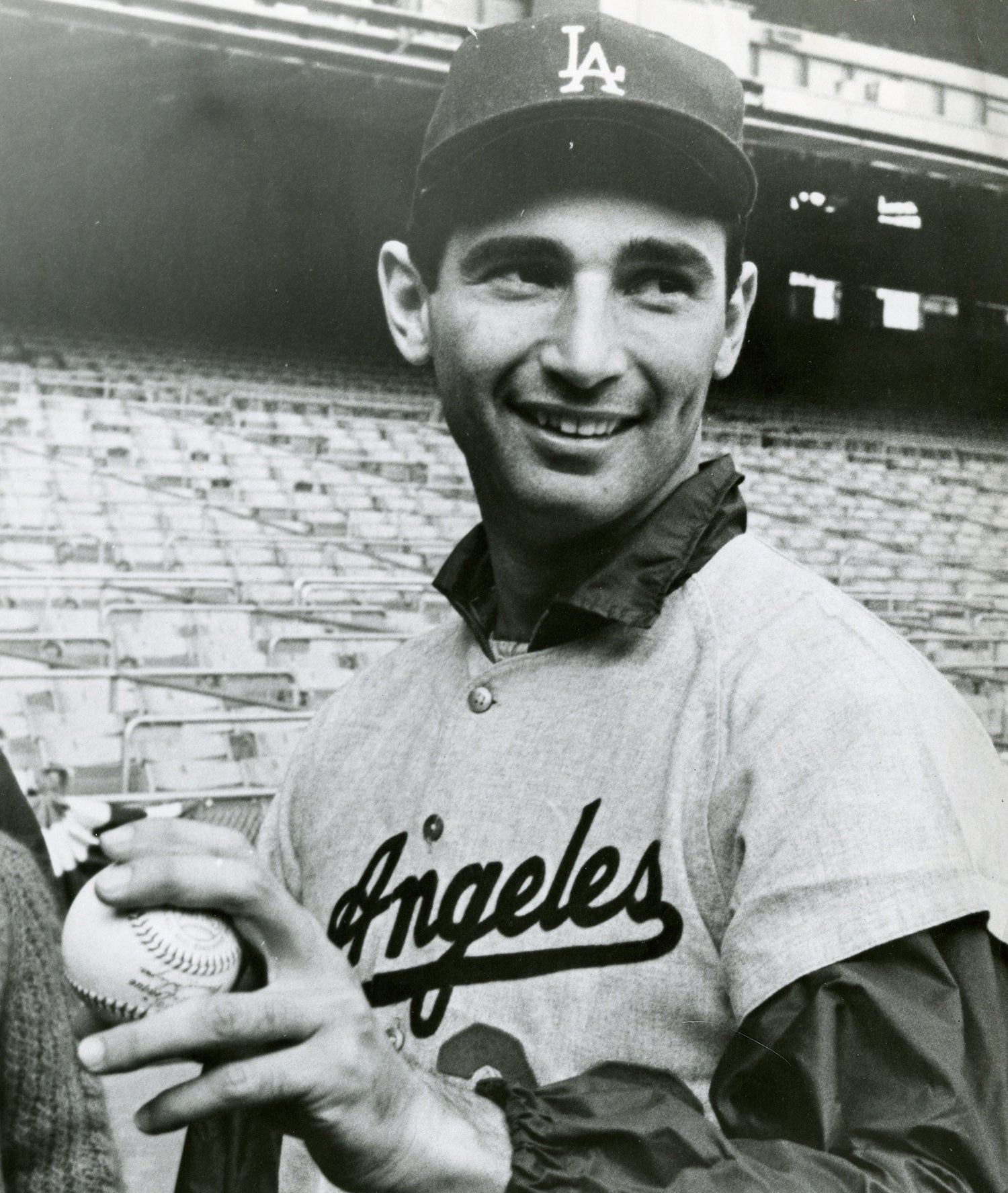

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Mudcat Grant

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

The baseball season has not yet arrived, but good news came earlier this month when Whittier College announced that it was giving an honorary degree to Jim “Mudcat” Grant. On February 8, Whittier College officially conveyed an honorary doctorate of humane letters on Grant, citing him for the exemplary way that he overcame discrimination in becoming a baseball success. The college also noted Grant’s work as a researcher and author, one who has shown dedication to the cause of promoting African-American baseball and its history.

During his younger days, Mudcat never had the opportunity to attend college, so it’s only fitting that one of the game’s great teachers and ambassadors receive a diploma from a fully accredited college. We can all learn a lot from an intelligent and enthusiastic man whom some have called a younger version of Buck O’Neil.

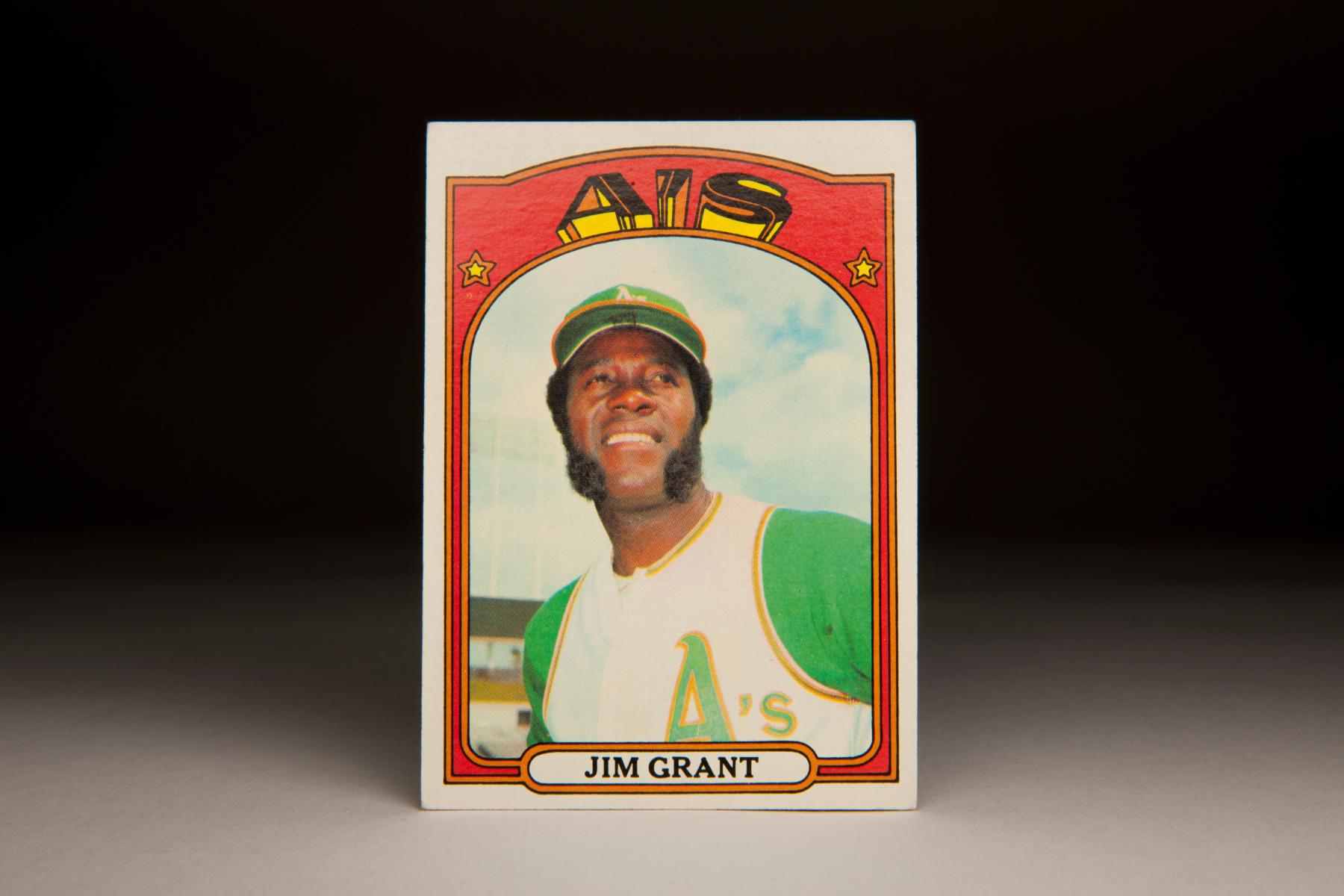

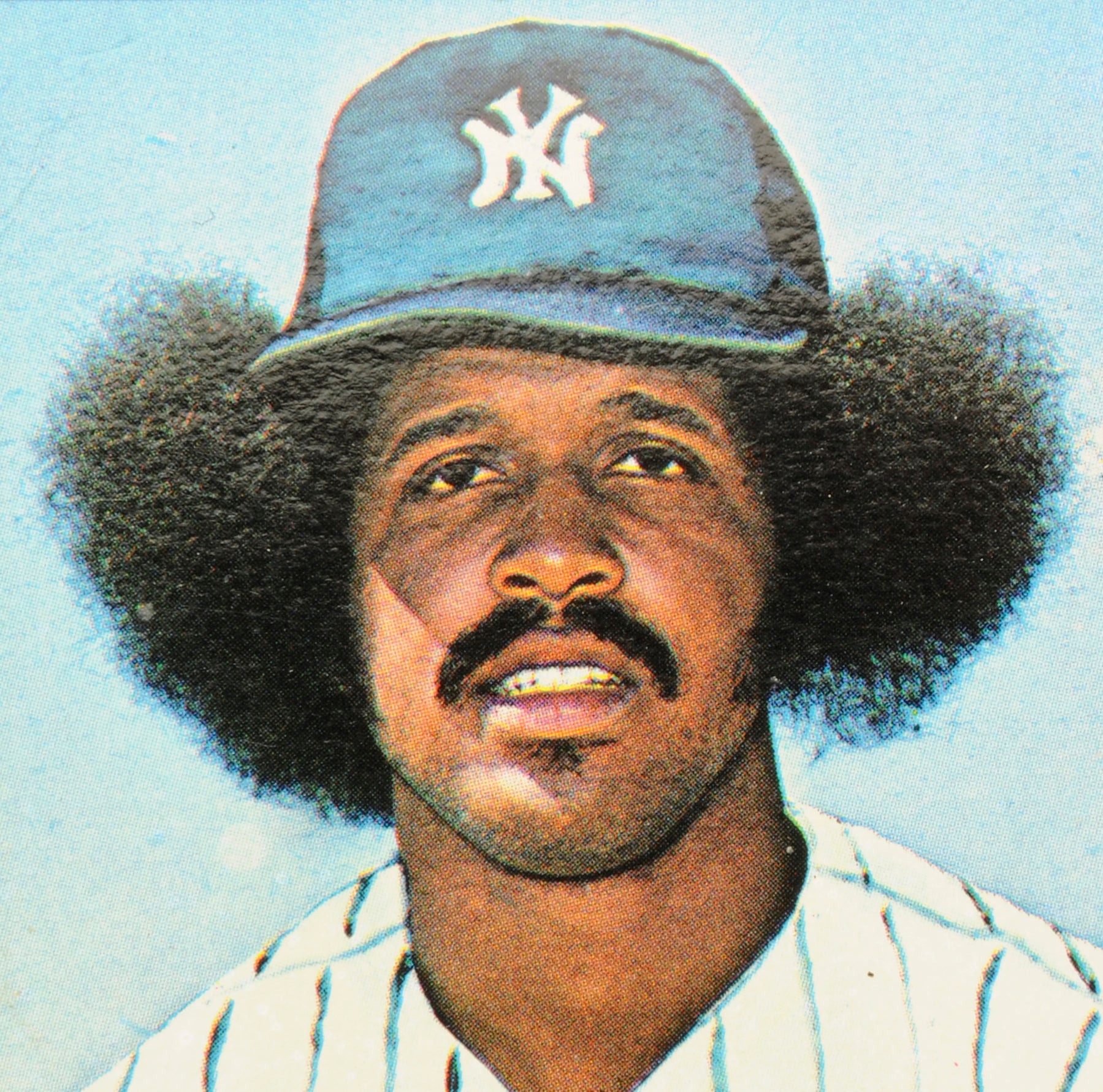

My first association with Mudcat came in 1972, when I collected this baseball card. That was the year that I started collecting cards. My trip to Gillard’s Stationery Store resulted in the acquisition of this card, part of my first pack of cardboard. At the time, I didn’t know anything about Grant as a player—he could have been the batting coach for all I knew—but I loved that card right from the start. From the green and white sleeveless Oakland uniform to those funky, oh-so-1970s, mutton-chop sideburns, this was a cool card to have.

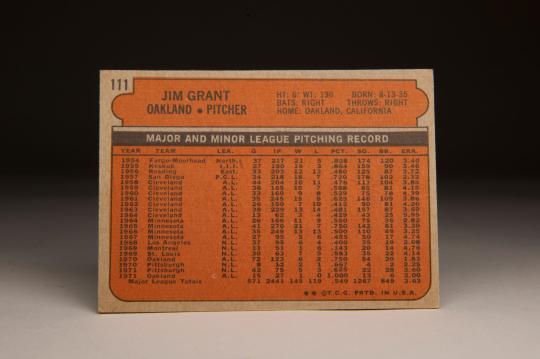

Little did I realize that this would be the last Topps card issued for Grant as an active player. I had no idea that Grant already had been released by the Oakland A’s during the winter. I never thought that would have happened, considering the fairly impressive statistics on the back of Grant’s card.

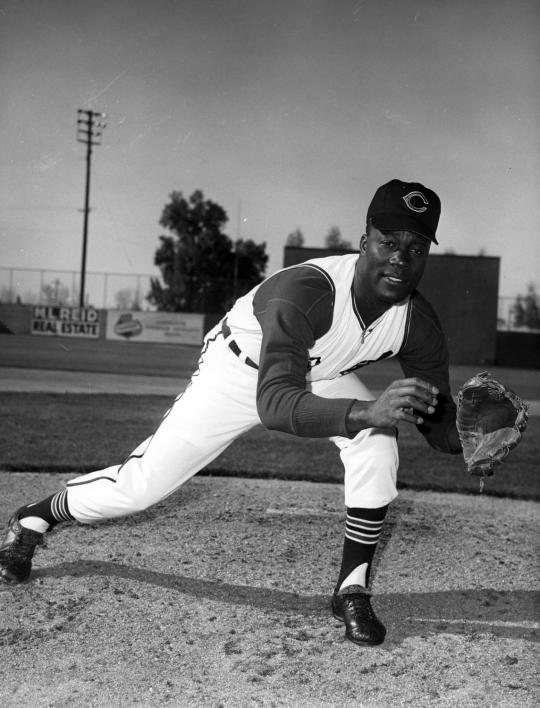

Before we get to the events of 1971 and ’72, Grant’s story needs a retelling from earlier days. By the time that Grant graduated from high school, the Negro Leagues had seen their heyday come and go. He signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1954, beginning a steady four-year climb through their minor league system. (It was while in the minor leagues that a teammate nicknamed him Mudcat, mistakenly thinking that he was from Mississippi, the Mudcat State.) He made the Opening Day roster in 1958, pitching creditably in 44 games, including 28 starts.

As a rookie, Grant roomed with veteran star Larry Doby, the first man to break the color barrier in the American League and the man who just happened to have been Mudcat’s idol as a youth. “So I got in the room and [the rest of the players] were still at the ballpark. And then Larry came in a little bit later… Larry said, ‘Well, you must be Mudcat Grant.’ I said, ‘Yes sir, Mr. Doby.’ He asked, ‘Do you like that bed over there?’ I said, ‘Yes sir, Mr. Doby.’ He said, ‘We’re going to have to get rid of this, ‘Yes sir, Mr. Doby.’ I said, ‘Yes sir, Mr. Doby.’

“He taught me just about everything. I know the history of Larry Doby, because late at night Larry would pace. He would yell, he would scream. This is how he would overcome some of the difficulties that he had to go through. I know it was difficult. And then he taught me, ‘This is what you’re going to have to face [as a Black player]. You’ve got to face it, and when you cross the white lines, you better win. It ain’t about, Oh, this is so bad for me. You better win. Because if you don’t win, good-bye, see you later.’ ”

Grant learned a lot from Doby, particularly when it came to dealing with Jim Crow segregation at hotels, restaurants, and even water fountains. On the field, Grant finally graduated to a full-time starting role in 1961, giving the Indians 15 wins and 244 innings. Alternating bad and good years in 1962 and ’63, Grant began to frustrate the Indians with his fits and starts. The situation reached a boiling point in 1964, when he started the season so badly that the Indians decided to make a change. At the June 15 trading deadline, Cleveland dealt Grant to the Minnesota Twins for the uninspiring package of pitcher Lee Stange and an infield/outfield prospect named George Banks.

The move to Minnesota rejuvenated Grant. With a new pitching coach and a better supporting cast of players around him, Grant bloomed into stardom. The Twins made Grant a full-time starter and watched him spin a 2.82 ERA. The situation only improved from there. In 1965, the Twins hired Johnny Sain as their pitching coach. Sain’s influence helped Grant become a workhorse: He made 39 starts, completed 14 games, and led the league with six shutouts and 21 wins. The latter statistic put Grant in the record books as the first Black pitcher in American League history to win 20 games in a season.

With Grant leading the rotation, the Twins claimed the American League pennant and earned a World Series berth against the Los Angeles Dodgers, who featured twin aces in Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale. Grant did all he could, winning two of three starts against LA (and even hitting a home run), but the Twins fell short in seven tough games.

Grant continued to pitch well in 1966, but injuries rendered him ineffective in 1967. Now on the wrong side of 30, Grant became expendable. Twins owner Calvin Griffith, who didn’t like Grant’s preference of Jazz music, traded him and slumping shortstop Zoilo Versalles to the Dodgers for catcher John Roseboro and pitchers Ron Perranoski and Bob Miller.

With a full rotation, the Dodgers moved Grant to the bullpen, where he excelled. His 2.08 ERA became even more noteworthy in the context of his lack of strikeouts. Grant struck out only 35 batters in 95 innings, but opposing hitters failed to make solid contact against him.

As it turned out, Grant lasted just the one season in LA. With the expansion draft coming up, the Dodgers left Grant unprotected; the Montreal Expos swooped in and took the veteran right-hander. That selection led to a dose of controversy in the spring, after Grant and the Expos had reported to Spring Training in West Palm Beach, Fla. Grant’s teammate, veteran shortstop Maury Wills, went to a bar with a sportswriter and photographer. Wills was almost immediately asked to leave “because they didn’t serve colored people.”

Grant, who had experienced such racism earlier in the decade, couldn’t ignore the situation in 1969. A native of Florida, Grant wrote a letter of protest to the state’s governor, Claude Kirk. As Grant explained to the Associated Press, “Wills is an outstanding citizen of this country. He should be accepted as a citizen, not as a Black man, who has to be told that he can’t do this or that.”

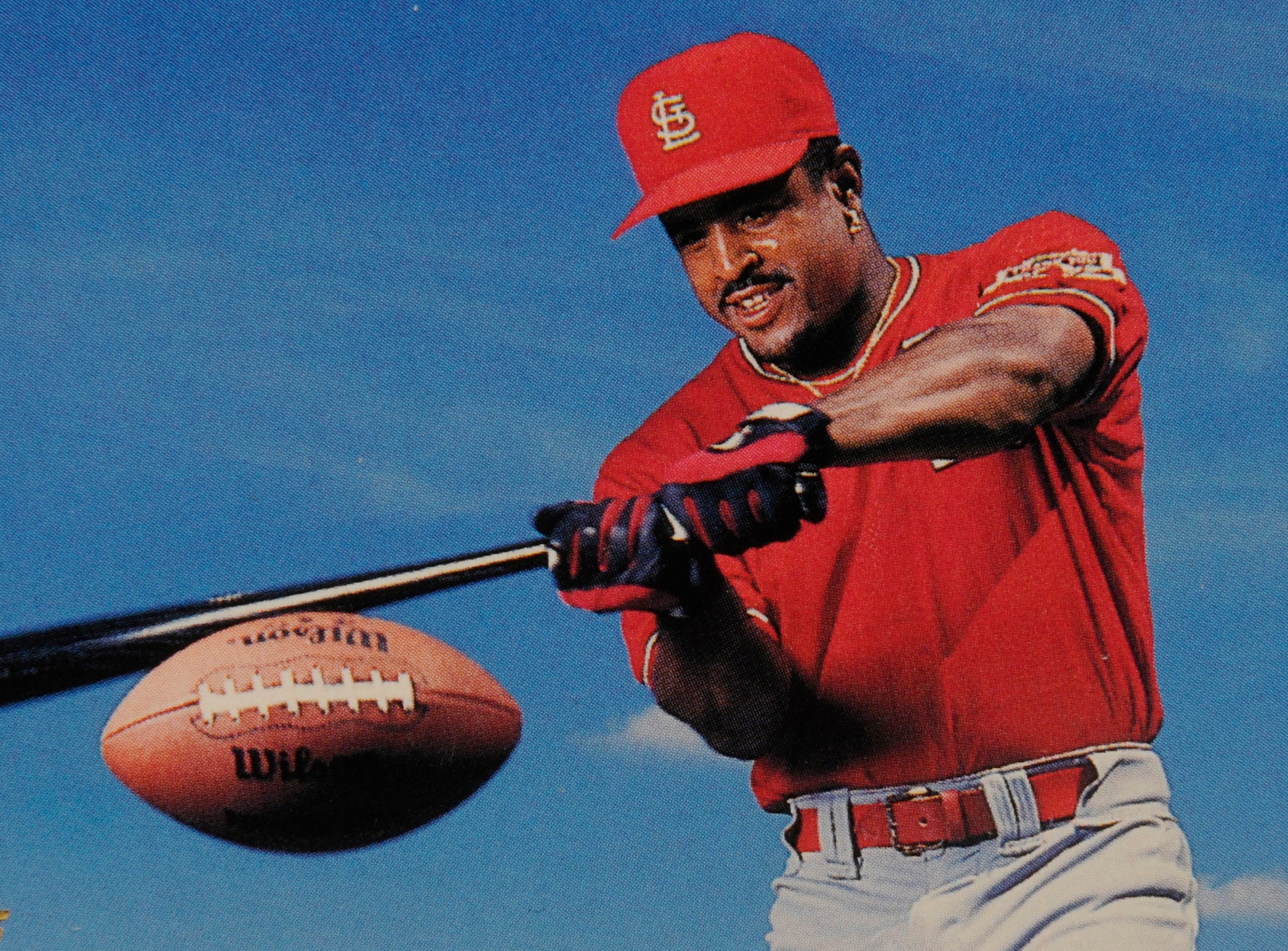

On the field, Grant’s pitching convinced the Expos to make him their Opening Day starter. In reality, a young and building team like Montreal didn’t need a 33-year-old pitcher, so in June, the Expos traded off their would-be ace. They sent him to the St. Louis Cardinals for a journeyman reliever named Gary Waslewski. Grant finished out the season in obscurity, pitching in middle relief for the also-ran Redbirds.

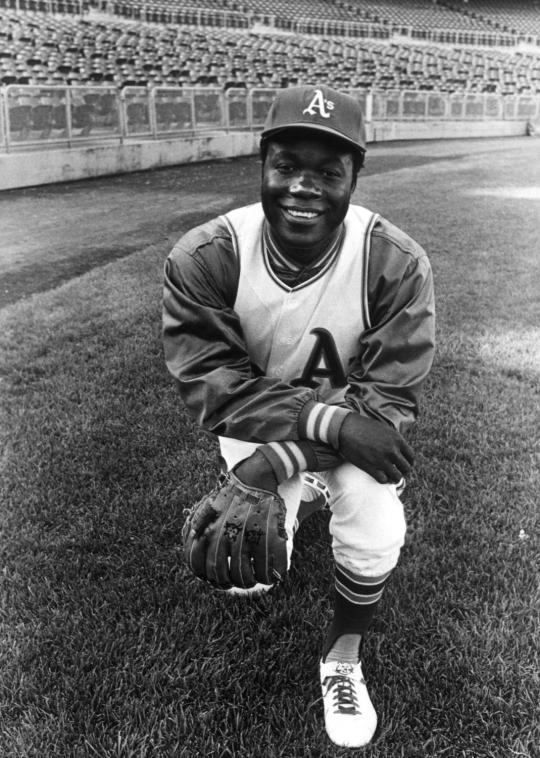

Then came the second break of Grant’s career. That winter, the Cardinals sold Mudcat’s contract to the Oakland A’s, who needed a closer. The A’s called on Grant, who made the transition with ease, racking up 24 saves and a career-best ERA of 1.82.

Grant performed another important service for Oakland. Working with a young Rollie Fingers, who had been a failed starter, Grant taught the young right-hander how to warm up properly in the bullpen, and how to prepare for each outing. Essentially, Grant laid the groundwork for Fingers to succeed him as Oakland’s closer.

That move became relevant in mid-September, when the A’s traded Grant to Pittsburgh for young outfielder Angel Mangual. Oakland writers reacted to the trade with varying degrees of stunned shock. Some speculated that the move came after Finley heard about Grant making a facetious remark on the radio about ownership “interfering” with the manager. It was an inconsequential jab, a humorous throwaway line, but Finley may have taken it far too seriously.

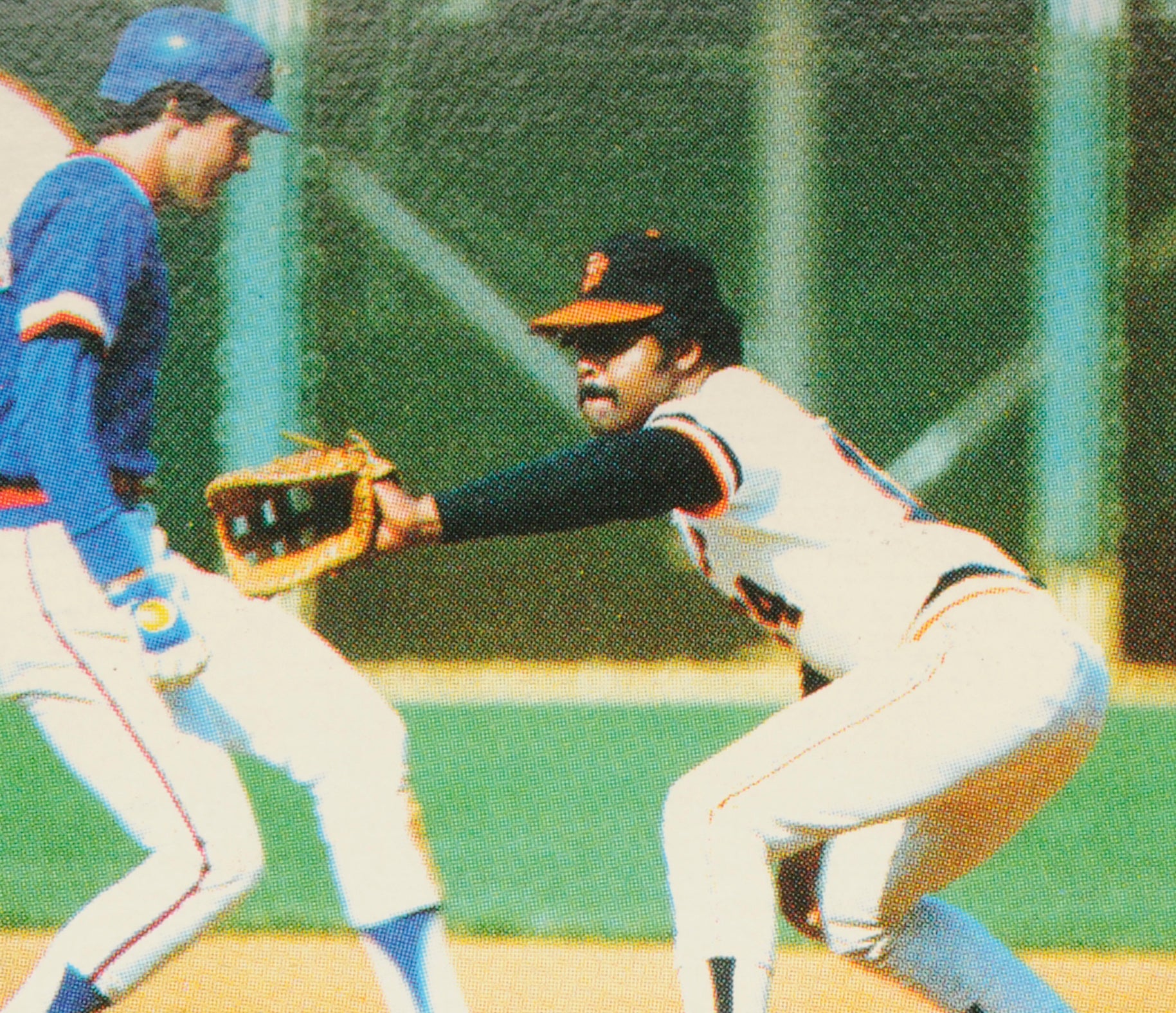

Fitting in well with the racially-integrated Pirates, Grant pitched effectively down the stretch, as the Bucs clinched the National League East. He continued that run into 1971, but an overcrowded bullpen made him expendable later that summer. On August 10, the Pirates sold him back to Oakland.

Grant pitched beautifully for the A’s over the final two months, to the tune of a 1.98 ERA, earning himself return trip to the postseason for the first time since 1965. Although Mudcat appeared to have plenty of life left in his 36-year-old arm, the A’s released him after the season, primarily because Finley didn’t want to foot the bill on the right-hander’s expensive contract. As a seven-year-old baseball fan, I didn’t understand how money could alter a front office’s opinion of a player. Either a guy could play, or he couldn’t. Lesson learned.

In what remains a mystery to me to this day, no other major league team would give Mudcat a spot on its 25-man roster. Several teams seemed needy of relief help (including the Boston Red Sox, Kansas City Royals and Chicago Cubs) but only one team—the non-contending Indians—gave him as much as a non-roster Spring Training invite. Grant had started his career with the Indians, so the move seemed motivated by sentiment as much as anything else. Grant reported to spring training, but did not impress the Indians’ brass. Instead, the Indians offered him a consolation prize, a minor league deal to pitch at Triple-A Portland, but Grant turned down the contract.

Grant did decide to continue his career by pitching in the minor leagues, but not with Portland. Instead, he signed on with the Iowa Oaks, the Triple-A affiliate of the A’s. Grant pitched well for the Oaks, but no major league team came calling that summer. At the end of the season, Mudcat called it quits, ending his career with 145 wins, 119 losses, 53 saves, and a respectable ERA of 3.63.

After his playing days, Grant continued to pursue another one of his talents. At one time the front man for a group called “Mudcat and the Kittens,” he appeared often at nightclubs. Grant also remained connected to baseball by taking a job as an Indians broadcaster. After a short broadcasting stint with the A’s, Grant left baseball to become a special marketing director for Anheuser-Busch in the Cleveland area. He also worked for the speakers’ bureau of the NBA’s Cleveland Cavaliers. Later on, Mudcat authored the book, The Black Aces, about the African-American pitchers who have won 20 or more games in a season.

In the 1980s, Grant began operating a nationwide program called “Slug-Out Illiteracy, Slug-Out Drugs” in Los Angeles, where he encouraged former players to put forth an anti-drug message during instructional clinics. And as part of his efforts to help former players who are struggling with financial and medical problems, Grant has faithfully served as a board member of the MLB Players Alumni Association. One of the players he tried to help was Leon Wagner, who died from drug abuse; he was homeless and destitute. Mudcat did his best to rescue “Daddy Wags,” setting him up with jobs in fantasy camps and arranging places for him to live, but Wagner ultimately returned to a life of addiction.

In 2004, I was lucky enough to meet Mudcat for the first time. He and his former Pirates teammate, Al Oliver, came to the Hall of Fame to participate in a special program for Black History Month. Sometimes we’re disappointed when we meet our heroes, but that was not the case with Mudcat, or Al. Both were phenomenal, interacting wonderfully with fans in the Bullpen Theater, giving important insight into baseball’s struggle to connect with African-American youth, and entertaining us endlessly with their stories at dinnertime.

Every once in awhile, our baseball cards come to life. That’s what happened that February day in 2004, when a magical man named Mudcat came to town.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame