- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Herb Washington

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Herb Washington

When fans take their first stroll through the new Hall of Fame exhibit, Whole New Ballgame, they might notice a plethora (to borrow a phrase from Howard Cosell) of baseball cards on display in the various cases. Serving as enticing signposts throughout Whole New Ballgame, the 72 cards on exhibit include cards that range from the early 1970s to the 2010s.

The array of cards includes a number of selections from the 1970s, everything from Curt Flood’s 1970 Topps card (which shows him with the team for which he never played: the Philadelphia Phillies) and the hairdo collection headlined by Oscar Gamble to the four 20-game winners of the 1971 Baltimore Orioles and that perpetual infield employed by the Los Angeles Dodgers (featuring Garvey, Lopes, Russell and Cey).

Baseball cards have been extremely popular since the 1950s, but they seemed to gain unforeseen and unprecedented momentum in the 1970s. That’s when Topps introduced such trends and features as action photography and black borders (1971), highlighted action cards and mind-blowing colors (1972), positional silhouettes (1973), multi-colored borders (1975), traded cards (1972, ’74, and ’76), airbrushing madness (1977) and classically simplistic designs (1978).

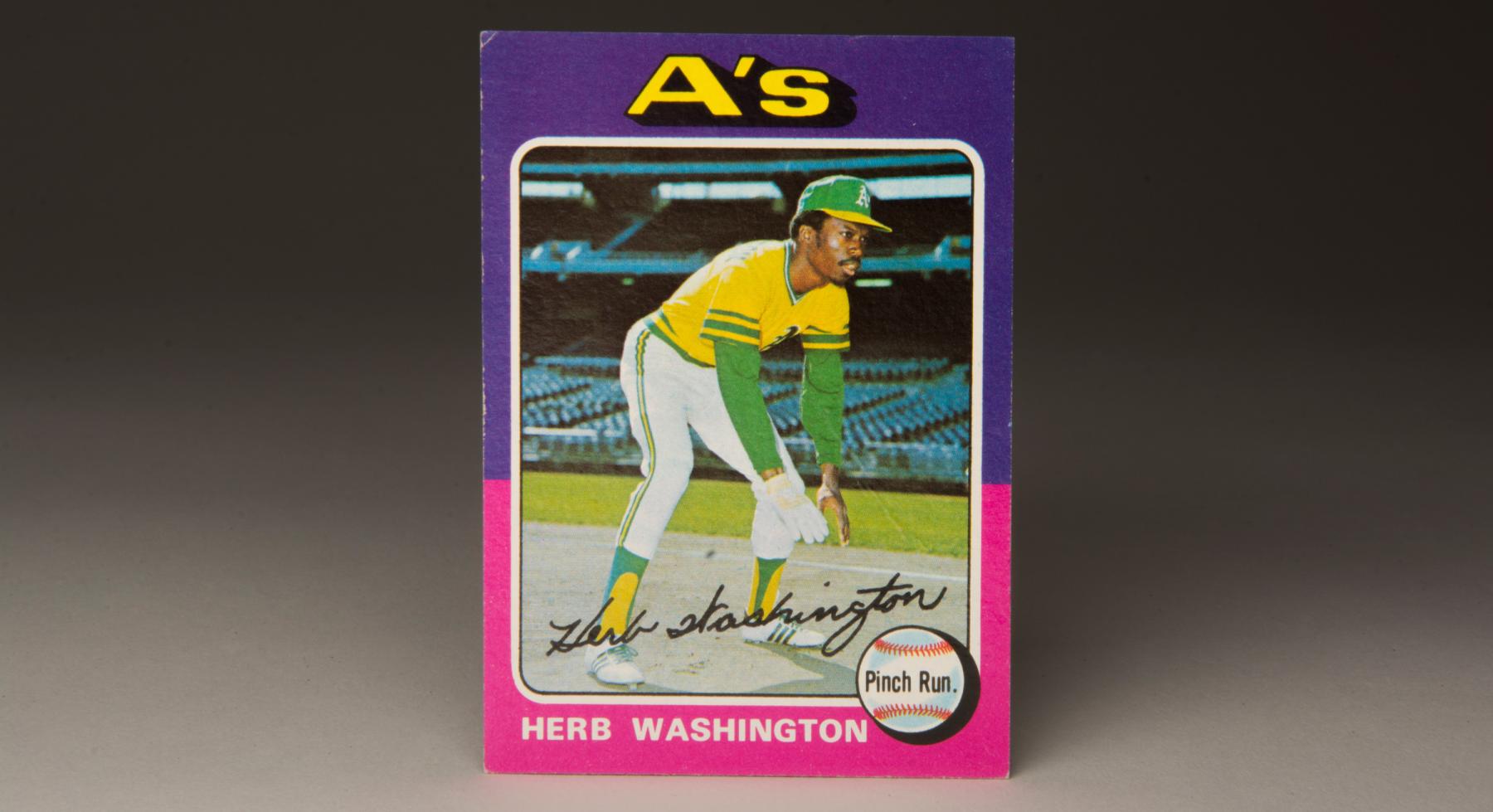

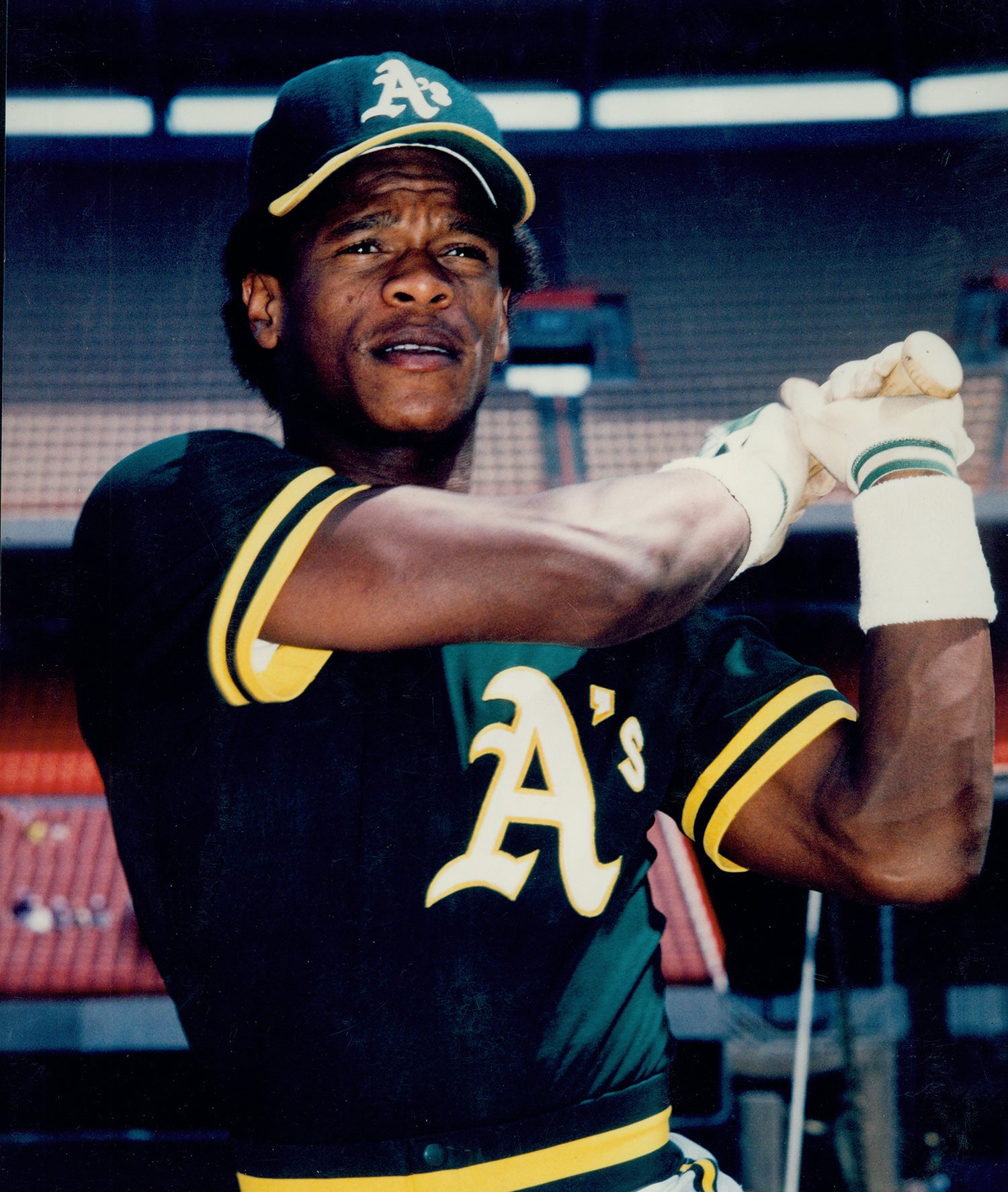

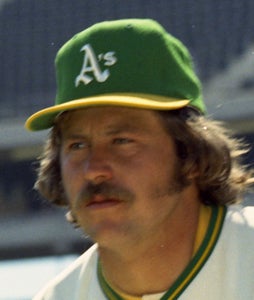

Also included among the collage of 1970s baseball cards is arguably the most striking of the bunch: the 1975 Topps card of one Herb Washington. Emblazoned with the gold jersey and green trim colors of the Oakland A’s, and outlined in an outlandish border of purple and pink, this card smacks of the 1970s in a way that is not at all subtle, but is very much psychedelic.

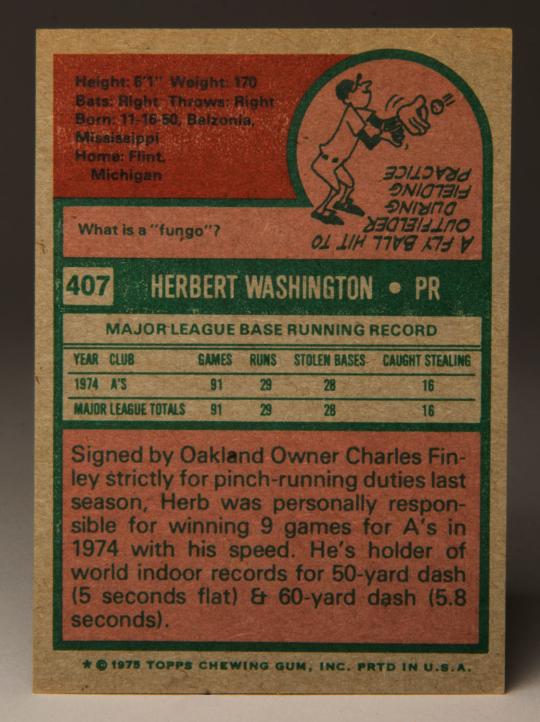

The Washington card might also be the most unusual one on display. In the lower right-hand corner of the card, printed in black type within the silhouette of a baseball, we see Washington’s position. He is not listed as a second basemen, or an outfielder, or even a designated hitter. No, his position is listed as “Pinch Run.” It’s an abbreviation for “Pinch Runner,” making this an historic card: the only Topps card ever produced that lists such a position as a baseball player’s method of employment. We can find many baseball cards that list “designated hitter” or “manager,” or even cards designated for coaches, but this remains the only Topps card ever produced that indicates the specialty of pinch-running.

Of course, there really is no other way to describe Washington’s role with the A’s in the mid-1970s. He did not play a position in the field, did not take an at-bat, and did not throw a pitch from the mound. Washington was not really a baseball player, at least not in the classic sense. All he did was pinch-run, often in the late innings and usually when the A’s needed a stolen base in a close game. That’s the very specific role that Washington filled, with mixed success, over the span of two seasons. And that’s likely why the Topps photographer asked him to stand on the infield dirt in the hours before game time at the Oakland Coliseum and pretend to take a lead off first base against a pitcher who wasn’t even there.

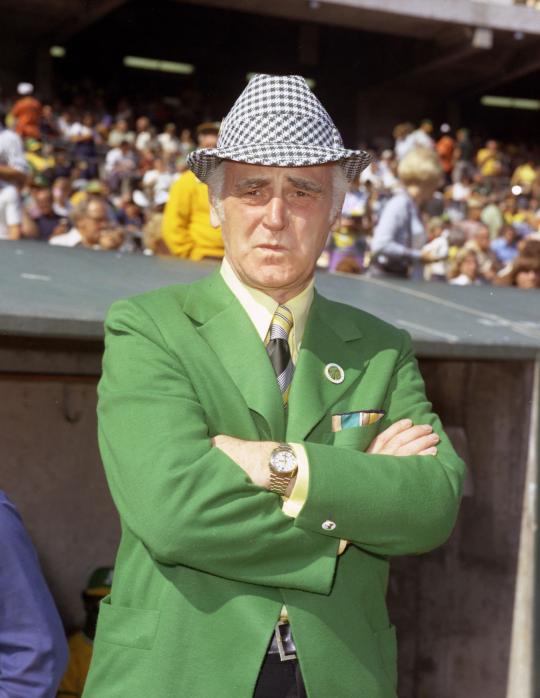

As owner and general manager of the A’s, Charlie Finley believed in specialization within the game. He was one of the first owners to champion the cause for the DH in the 1960s. He also believed in the value of carrying players on the 25-man roster who could do little else but run fast and steal bases. Beginning with Panamanian Allan Lewis in 1967, Finley had been employing pinch-runners for several seasons. Lewis could play the outfield and swing the bat a little, but his primary talent was his speed, which earned him the nickname, “The Panamanian Express.”

From 1967 to 1973, Lewis appeared in 156 games for the A’s, but came to the plate only 31 times and played only a few games in the outfield. The vast majority of the time, Lewis appeared as a pinch-runner. He was fairly adequate in that role, stealing 44 bases in 61 attempts for a success rate of 72 percent. He was no Lou Brock or Rickey Henderson, but he also wasn’t Don Mincher, who stole 24 bases while being caught 32 times during his career as a slugging first baseman.

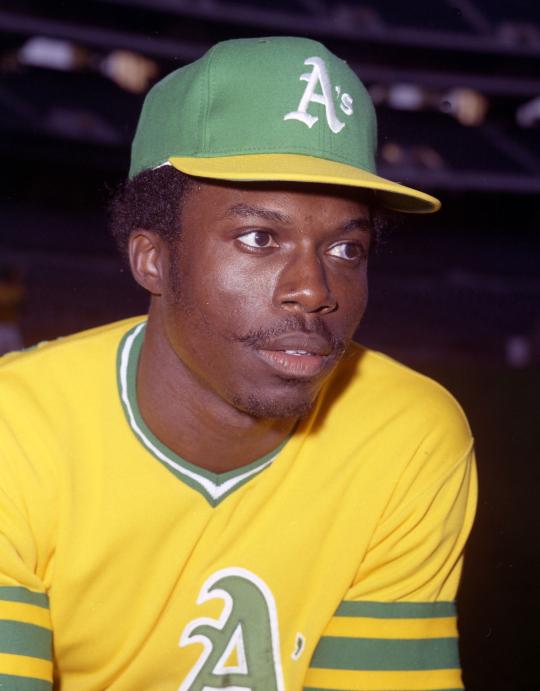

By the end of the 1973 season, Lewis was 31 years old and losing some of his footspeed. So Finley discarded him prior to the 1974 campaign. That left the A’s without a pinch-runner on their roster. Finley couldn’t have that. With only two weeks to go in Spring Training, Finley unleashed a surprise announcement. He declared that the A’s had signed 22-year-old Herb Washington, nicknamed “Hurricane,” to serve as their designated pinch-runner in 1974.

The move raised eyebrows across all Spring Training sites, principally because Washington had never played baseball above the level of high school. In fact, Washington had not played ball since his junior year in high school. What Washington did do well was run. A world class sprinter at Michigan State University, he had set world records in the 50-yard and 60-yard dash.

The A’s put out a press release, written by Finley, which heralded Hurricane Herb’s arrival and included a full endorsement from Oakland manager Alvin Dark. “Finley and Dark feel that Washington will be directly responsible for winning 10 games this year,” the release stated in no uncertain terms. In reality, Dark had said nothing of the kind. It was Finley who believed such a statement, as outrageous as it was. Dark, who had only recently been hired to replace Dick Williams, liked Washington and supported his signing, but knew that Finley was exaggerating the value of his new pinch-running toy.

To coincide with the historic signing of Washington, the A’s announced the signing of former Los Angeles Dodgers standout Maury Wills as a Spring Training instructor. As part of a special six-day crash program, Wills would tutor Washington on the basics of base running. The program would include instruction on how to take a proper lead and the correct way to round the bases. Wills would also work with Washington on his sliding skills, teaching him how to slide headfirst, as a way to avoid injuries to his legs.

Essentially, Wills served as Washington’s personal instructor for six days that spring. (Curiously, Wills wore a Dodgers uniform, and not the color of the A’s, during his week-long stint in the Oakland camp.) While the A’s had several future Hall of Famers on their roster - namely Reggie Jackson, Jim “Catfish” Hunter, and Rollie Fingers - none of them had their own personal coach earning money on the Oakland payroll.

The signing of Washington did not please many of the A’s veterans. “That’s a joke,” exclaimed Gene Tenace, the team’s catcher/first baseman. “This is going to cost somebody who should be in the major leagues a job.” Rather than carry an extra catcher, or an extra pinch-hitter, the last spot on the roster would go to a track star.

As soon as Opening Day, Washington’s presence on the roster created direct controversy. With the A’s up 7-0 in the seventh inning, Dark removed his starting left fielder, Joe Rudi, replacing him with a pinch-runner - none other than Washington. Normally the most congenial of players, Rudi was none too happy about being taken out of a one-sided game for a pinch-runner. He said the decision to replace him with Washington made him feel like “half a ballplayer.”

Dark continued to use Washington regularly throughout the season, often drawing the wrath of his players when they were removed for the pinch-running specialist. For the season, Washington appeared in 92 games, an incredible number for a pinch-runner. But he stole only 29 bases, and did so in 45 attempts, for a poor percentage of 64 percent. According to the consensus of baseball opinion, a success rate of at least 75 percent is considered the break-even for base runners, leaving Washington well short of that mark.

At times, Washington showed little understanding of game situations. On one occasion, he asked Dark if he wanted him to steal second base. Pointing toward the infield, Dark informed Washington that there was already a runner on second base.

Washington’s low point of the season came during the World Series. Trailing 3-2 in the ninth inning of Game 2, Dark inserted Washington as a pinch-runner for Rudi at first base. With one out and Washington representing the game-tying run, the move made sense.

Washington took a large lead off of first base. Dodgers relief ace Mike Marshall, who by coincidence was a Michigan State alumnus just like Washington, owned a deceptively quick spin move to first base. Marshall stepped off the rubber three times, making Washington retreat to first base each time. Rather than take a more cautious lead, Washington remained aggressive. Marshall then attempted another quick spin move. With his right leg, Washington leaned momentarily toward second, and then tried to turn his body back to first base. It wasn’t even close. First baseman Steve Garvey applied the tag well before Washington touched first base, recording an obvious out. The pickoff essentially sealed a Game 2 loss for the A’s and placed the goat horns firmly on the head of Herb Washington.

Some of the A’s, including Reggie Jackson, offered Washington a pat on the shoulder and words of encouragement. Thankfully for Washington, the base running blunder did not cost the A’s in the long run. Oakland won the next three games of the World Series to finish off their third consecutive world championship.

Finley didn’t want to admit it publicly, but the Washington experiment had provided only middling results. Washington certainly didn’t account for 10 wins. The A’s could only hope that his basestealing technique would improve in 1975.

During the spring of ‘75, Finley announced another surprise acquisition. The A’s purchased outfielder Don Hopkins from the Montreal Expos. Hopkins was a career minor leaguer who had never risen above Class A ball in the minor leagues. Listed as a non-prospect by most scouts, Hopkins had failed to hit a home run in five big league seasons. But he could run very fast. Rather remarkably, the A’s announced that they would use Hopkins as their second pinch-runner. “You’re kidding,” said A’s captain Sal Bando, who could not hold back his disbelief.

By the early part of the 1975 season, Finley had collected three pinch-runners on his roster. The third entry was Matt “The Scat” Alexander, a utility player acquired from the Chicago Cubs. In contrast to Washington and Don Hopkins, Alexander brought legitimate versatility to the table. He could play both the infield and the outfield, making him especially valuable to manager Dark.

By early May, Washington had appeared in 13 more games, stealing two bases and getting caught once. With Washington, Hopkins, and Alexander all taking up space on the roster, it seemed obvious that one of the specialty runners would have to go. On May 5, Finley made his decision. In order to make room for backup catcher Charlie Sands, the A’s requested waivers on Washington for the purpose of giving him his unconditional release. Finley’s great experiment had come to an end. Appearing in over 100 games in parts of two seasons, Washington had set an unofficial record by not once coming to the plate or playing a defensive position.

A few of the A’s players expressed some sympathy for Washington, who was a friendly sort and a man of high intelligence. But there were other players who were less accepting and who simply wanted him to go. Washington would not name names, but he made it clear that the experience had been difficult. “The toughest adjustment was putting up with egocentric ballplayers,” said Washington, “and a ton of bull from frontrunners on the team, frontrunners in the media, and frontrunners among the fans. Some of the players are nice guys. Some are jerks, too.”

In some ways, Washington would enjoy the last laugh. Not only did he earn a World Series ring as a member of the 1974 A’s, but he has been invited back to reunions held for those great A’s teams of the 1970s. Even more impressively, Washington has enjoyed remarkable success in the business world. He has owned a number of profitable McDonald’s restaurants and has held several positions with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Hurricane Herb has done just fine.

Not bad for a guy who never swung a bat or played an inning in the field of a big league game.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame