- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Chico Salmon

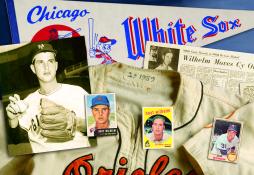

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Chico Salmon

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

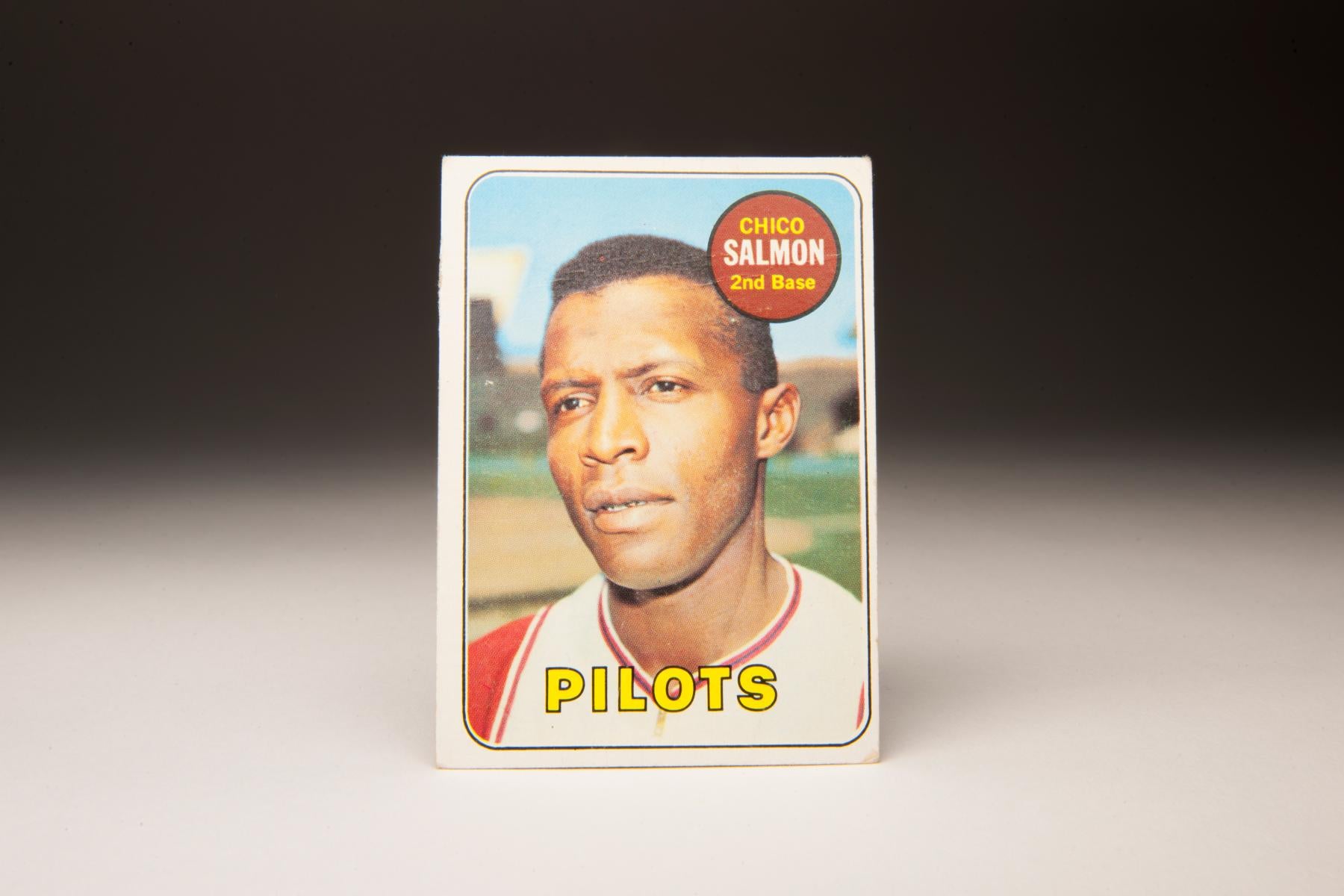

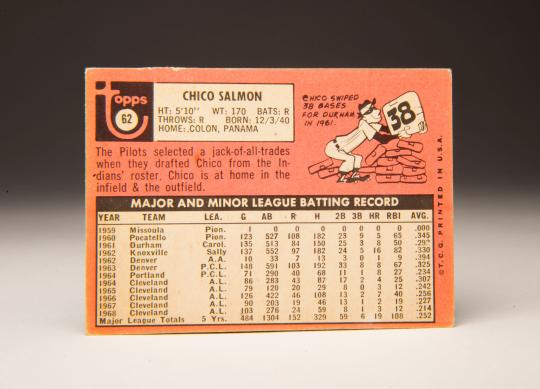

Chico Salmon seems to be perfectly at ease on his 1969 Topps card. In looking at this common card from the late 1960s, there is no way to tell about the phobia that Salmon once felt; he had a tangible fear of ghosts. In fact, he was so fearful of spirits from another realm that he refused to sleep in the dark; the light in his room would have to remain on throughout the night. Salmon’s fear apparently stemmed from his childhood years, when his mother and other members of his family warned him that ghosts could enter rooms at night if the windows were left open or if keyholes in the door were left unplugged. In order to combat the situation, Salmon typically stuffed chewing gum into the keyhole and a rolled-up towel under the door, all as additional protection against the spirit world.

Salmon’s 1969 card provides us with no evidence of the presence of ghosts, but it does give us a peek into how tumultuous his world was that spring. We see that Salmon is clearly wearing the iconic 1960s-era uniform of the Cleveland Indians, which featured a sleeveless vest and a bright red undershirt, even though the designation at the bottom of the card is spelled out as “PILOTS.” As it turns out, Salmon’s 1969 Topps card is the final one that shows him wearing the colors of the Indians, who left him exposed to the expansion draft. That decision allowed the brand new Seattle Pilots franchise to claim him, in the hope that Salmon would compete to become their everyday second baseman.

As it turned out, Salmon didn’t play for the Pilots either in 1969. The Pilots brought Salmon to Spring Training, but he lost the second base battle to Tommy Harper, a player with more power and raw offensive talent than Salmon. As a result, Salmon never appeared in a game for a Pilots team that would soon become famous because of Jim Bouton’s Ball Four.

Harper’s play not only reduced Salmon to a reserve role, but it also made him expendable. Near the end of Spring Training in 1969, the Pilots dealt Salmon to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher Gene Brabender and utility infielder Gordy Lund.

I first learned about Salmon in 1972, when he was wrapping up his career as a utility infielder with those Orioles. A native of Panama, Rutherford Eduardo “Chico” Salmon had the kind of Latino name that kids in the 1970s, including yours truly, butchered with regularity. I used to say his name like SAH-Mun, as in the fish, but it was actually pronounced Sahl-MAWN. Little did I know about Spanish accents and pronunciations back in those days. We also had no idea that his real first name was Ruthford. None of his cards indicated that; they all said “Chico.” It was a common nickname given to Latino players in the 1960s. Translated into English, Chico means “little boy,” a nickname that most grown men today would fight with some degree of resistance.

Signed by the Washington Senators as an amateur free agent in 1959, Salmon never made it to the Capital City. After the 1959 season, the Senators sold him to the San Francisco Giants’ organization. Salmon would be sold or traded three more times, to the Detroit Tigers, Milwaukee Braves, and the Indians, before he would eventually make his major league debut.

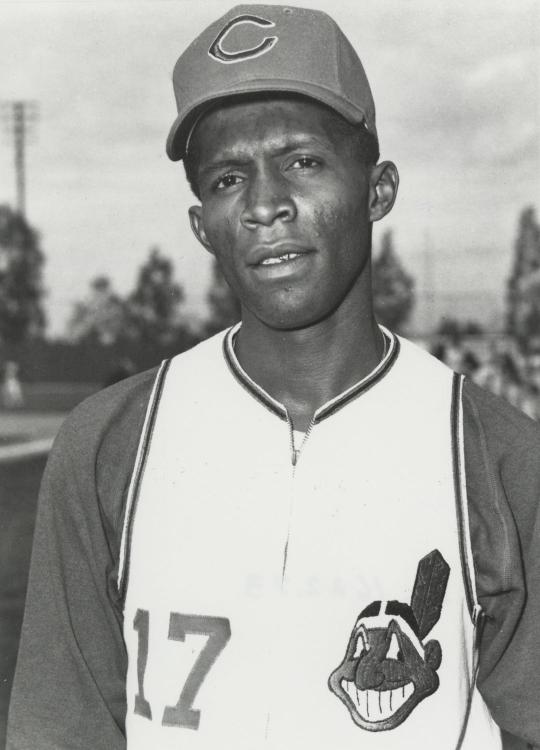

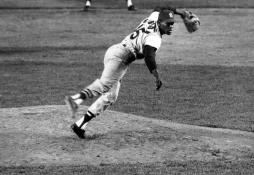

That finally happened in 1964, when he made the Indians’ roster as a utility player. He made an immediate impression on his teammates, who noticed the heart-shaped gold tooth that he sported in the front of his mouth. On the field, the versatile Salmon played right field, left field, second base, and first base. Unlike most utility infielders, he hit well, batting .307 in 283 at-bats that season. He also stole 10 bases, a testament to his above-average speed.

The winter of 1964 happened to be the year that his fear of ghosts came into conflict with his day-to-day life. A six-month stint in the military forced him to confront the fear. The Army would not allow him to sleep with the lights on in his barracks.

Even then, the phobia did not dissipate much. According to one of his cousins, Salmon never really conquered his fear of ghosts in the darkness. “You couldn’t turn the lights off in his house,” Alfredo Gonzalez told the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Unfortunately, Salmon developed another fear while stationed at Fort Polk in Louisiana. The military base and the surrounding area were riddled with snakes, which Salmon didn’t like. While the fear of snakes and ghosts continued to plague him, Salmon was finding success on the field. In 1966, he played so well that his manager, Birdie Tebbetts, suggested that he should be named to the All-Star team. That didn’t happen, but Salmon appreciated the sentiment.

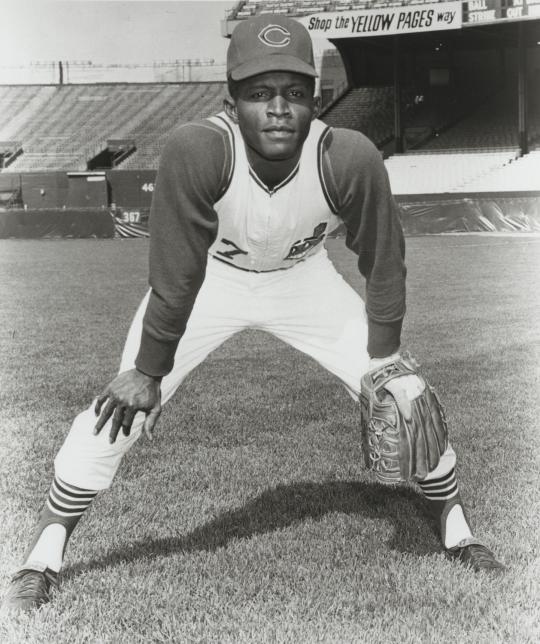

As a part-time player with the Indians, Salmon earned the nickname “Super Sub,” a tribute to his ability to play seven positions: the four infield spots and all three outfield locations. Salmon didn’t much care for the nickname, if only because he wanted one position to call his own, but the Indians felt that he would run out of gas if he played every day. Still, the Indians appreciated his versatility and value. As Indians coach George Strickland once said to Cleveland sportswriter Russell Schneider: “He has got to be the best tenth man in all of baseball.”

Salmon clearly had value to the Indians, but he was not a regular player, and therefore susceptible to being exposed to the expansion draft. After the Pilots drafted him and then traded him to Baltimore, Salmon lost out on any chance to play regularly (what with Boog Powell, Dave Johnson, Mark Belanger, and Brooks Robinson ahead of him). In terms of talent, the powerhouse Orioles were light years ahead of the fledgling Pilots. Still, Salmon did become the primary utility infielder, and a useful player, on some outstanding Orioles teams.

The trade to Baltimore created another opportunity for reporters to ask Salmon about his thoughts on the ghost world. “When I was young, I heard talk about evil spirits and I started to believe it,” Salmon told Doug Brown of the Sporting News. “I still do believe it, but I’ve never seen one. Older people told me that they had seen evil spirits and I don’t believe they’d tell me lies.”

Some of Salmon’s teammates teased him about his fear of demons. They also liked to poke fun at his fielding problems. Unlike most utility infielders, Salmon posed more of a threat with his bat and his legs than he did with his glove. As one of his Baltimore teammates said jokingly in 1970: “If Chico’s hands get any worse, we’ll have to amputate.”

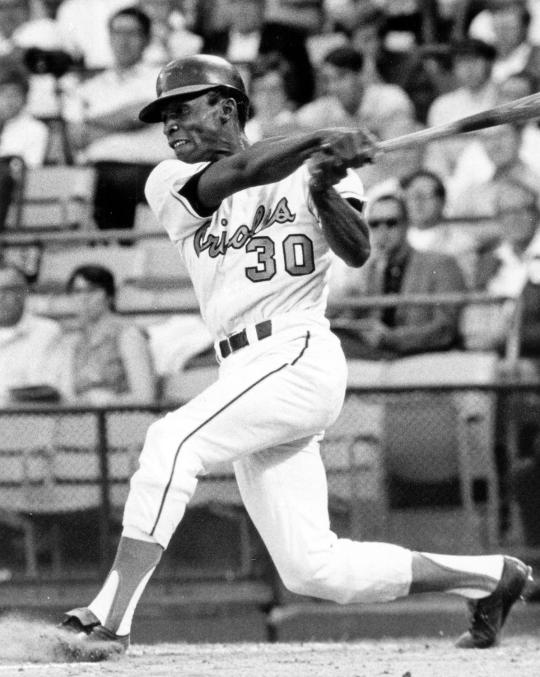

Despite his defensive deficiencies, Salmon helped the Orioles. He hit .297 in 1969, the year that the Orioles won the first of three consecutive pennants. On August 16, he enjoyed the game of his life: a 4-for-4 effort, including two home runs and six RBIs against the same Pilots team that had traded him in the spring.

Salmon also provided extreme versatility, flexible enough to play all four infield positions and spell Powell, Johnson, Belanger or Robinson on a moment's notice. Salmon earned some hardware along the way, playing for Orioles teams that won three league titles, including a world championship in 1970. His greatest baseball thrill came in the ’70 World Series, when he delivered a pinch-hit single in Game 2, igniting a five-run rally for the Orioles. “When I got the hit and [I was] standing on first base, I thought I was king of the world,” Salmon told sportswriter Jim Elliot of the Baltimore Sun.

Fluent in English, Salmon had the ability to turn colorful and often amusing quotations, a characteristic that made him stand out on an Orioles team with largely conservative personalities. For example, the Orioles’ addition of new all-orange uniforms in 1971 resulted in this vote of approval from Salmon. “I really like our new uniforms,” Chico told sportswriter Joe Falls. “They bring out the blackness in me.” Thanks to quotations like that, Salmon became known as one of the funniest of all the Orioles.

Salmon’s colorful nature obscured his excellent intellect for baseball and his commitment toward youth. When the Orioles acquired Tommy Davis to shore up their offense in the middle of the 1972 season, they released Salmon, ending his major league career. Salmon returned to Cleveland, where he had enjoyed playing, to engage in social work with youngsters at the Lincoln Recreation Center. It was a continuation of his efforts during his playing days, as he did his best to advise youth against the evils of drug abuse. All the while, he continued to play winter ball and then became a manager with the ill-fated Inter-American League in 1979. He later worked as a scout and served as a manager of the Panamanian team in the World Amateur Baseball Series. He continued to guide and help amateur teams in his homeland right up until his unexpected death from a heart attack in the year 2000.

It wasn’t merely that Chico Salmon had an interesting name, a colorful way with words, and an intriguing fear of ghosts. Those are all entertaining storylines, but Salmon was clearly a good man, too, one who willingly devoted his life to the game and to the noble pursuits of teaching and helping youngsters.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame