- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

There is perhaps no greater reminder that we are aging too fast than when we realize one of today’s ballplayers is the son of a former player we remember very well. For me, that reminder comes in high and hard with the developing career of Lance McCullers Jr., the promising young Houston Astros’ right-hander. The younger McCullers made his major league debut in 2015, striking out 129 batters in 125 innings and giving every indication that he just might be a future ace-in-the-making.

Well, this is culture shock for me. Because it doesn’t seem that long ago that I was following the career of Lance McCullers, Sr., a relief pitcher of some note back in the 1980s. The elder McCullers was a hard-throwing right-hander, much like his son, but he was almost exclusively a relief pitcher. At one time, the older McCullers seemed destined to become a star closer, the next Rich “Goose” Gossage or Dick “The Monster” Radatz. But it never quite worked out that way.

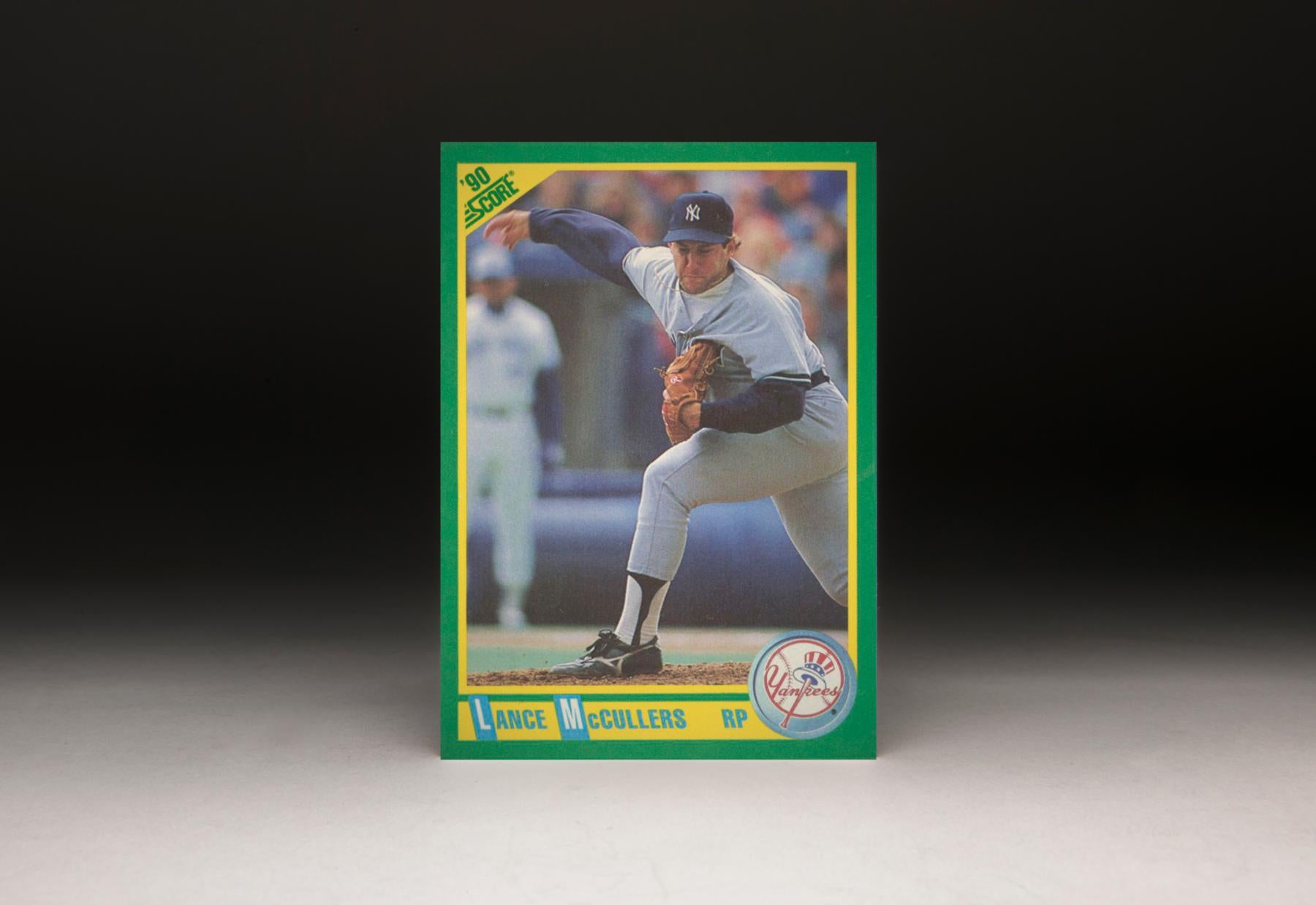

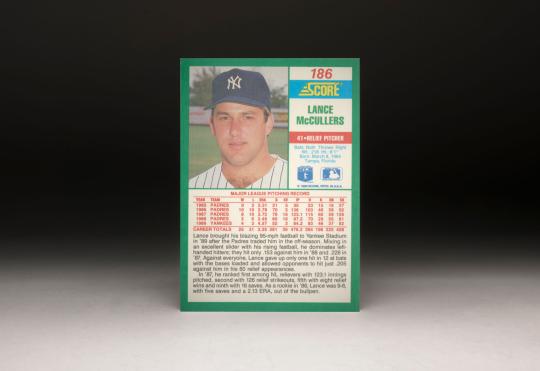

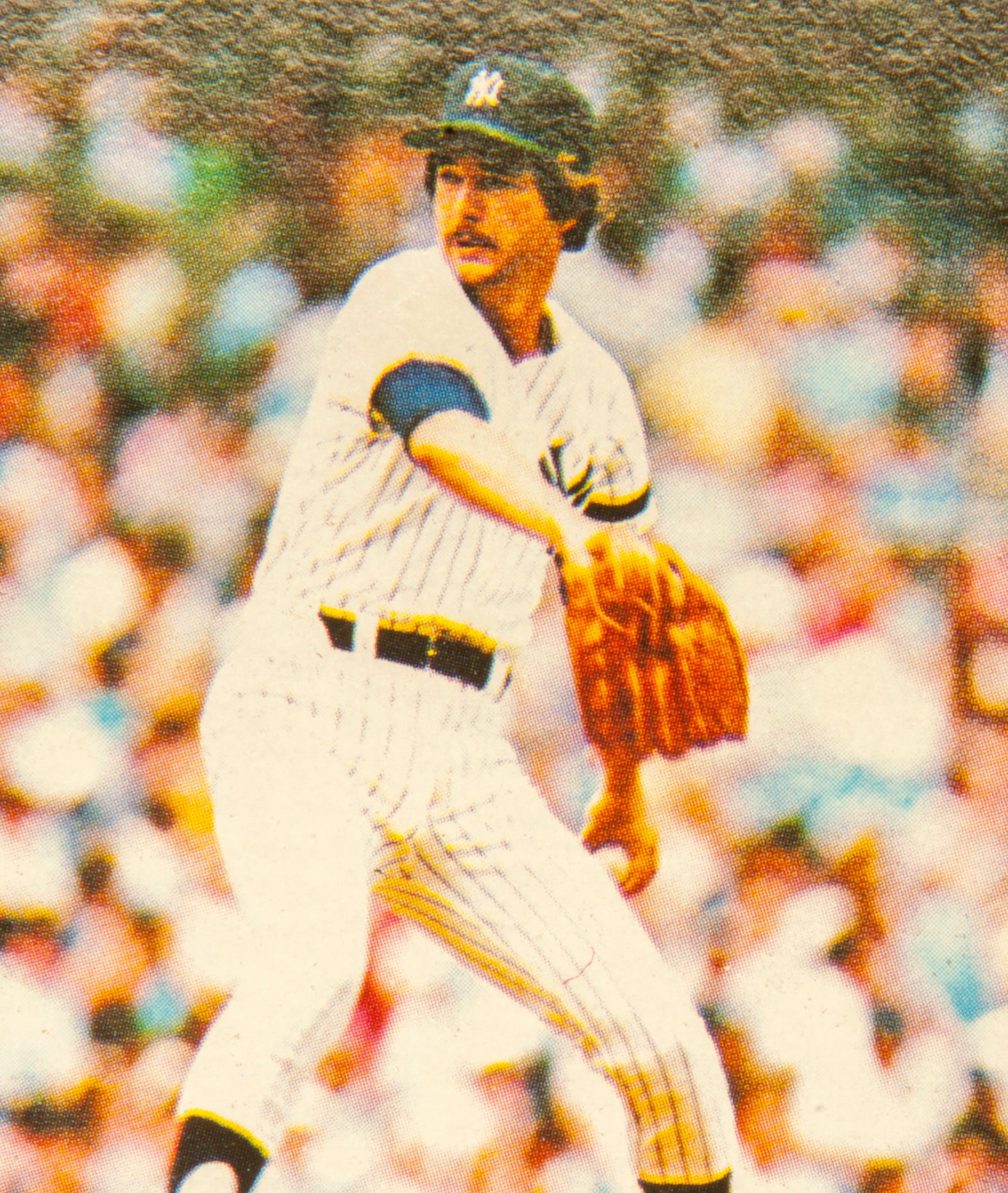

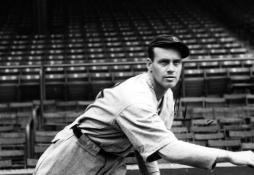

I’ve collected a few of McCullers’ baseball cards along the way, but my favorite doesn’t come from Topps; it was produced by a company called Score. Score put out its first set in 1988 and continued to produce cards until 1992. In 1990, Score issued one of it better sets, which featured a green border and a yellow inner frame for players in the American League. The set included a card of McCullers, who was a member of the New York Yankees’ bullpen. When I first saw the card, my eyes popped open a little wider.

I’m hardly an expert on the mechanics of a pitcher, but even I can tell that the finish of McCullers’ delivery in this game against the Toronto Blue Jays looks rather painful. When your head is completely turned toward first base just as you’ve released the ball toward home plate, there is something desperately wrong. The grimace on McCullers’ face only adds to the pain of observing this delivery. I watched McCullers a lot when he pitched for the Yankees, but never remember him finishing his pitching motion so awkwardly. Still, the camera doesn’t lie. The 1990 Score card reveals the imperfection in his delivery. So do a few other McCullers cards that were produced in the early nineties.

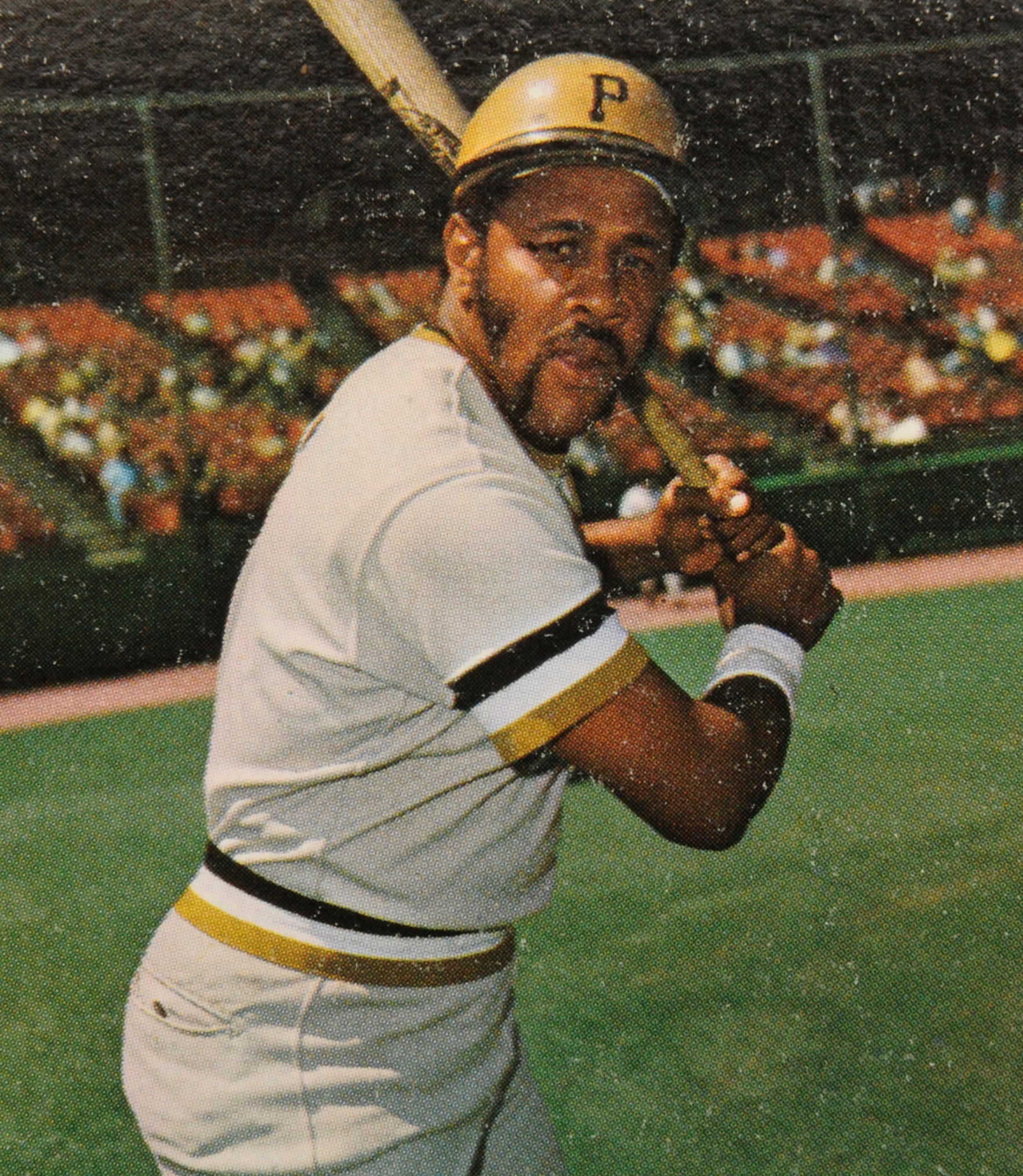

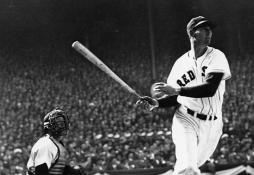

McCullers’ promising career began a few years earlier, when he was a young country boy prospect with the San Diego Padres. McCullers had the kind of talent over which scouts salivate, a powerful right arm that could manhandle opposing hitters. Some folks called him “Baby Goose” because his style mirrored Hall of Fame teammate Goose Gossage. Built big and burly, McCullers looked like a pitcher who could throw all day, down a big meal that night, and come back ready to pitch again the next day.

In 1985, McCullers showed great promise as one of Gossage’s set-up relievers. He appeared in 21 games, saving five and posting a standout ERA of 2.31. In 1986, manager Steve Boros showed so much confidence in McCullers that he called upon him 70 times, asking him to log 136 innings. That volume of innings would be unheard of for a reliever in today’s game - heck, there are starters who won’t reach that innings total this season—but it was not considered unusual for baseball in the 1980s.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

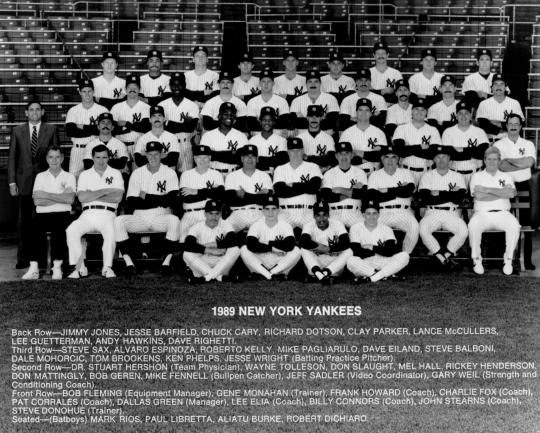

Pitching almost as much in 1987, McCullers remained the workhorse of the Padres’ bullpen, but his effectiveness waned. In 1988, the Padres cut him back to 97 innings, but watched him lower his ERA to a career-best of 2.49. Unfortunately, his periodic wildness resulted in him losing the closer’s role to Mark Davis, who pitched brilliantly in late-inning relief. Davis’ emergence made McCullers expendable; that winter, the Padres put together a package of McCullers, young right-hander Jimmy Jones, and outfield prospect Stanley Jefferson, sending them to the New York Yankees for slugging first baseman Jack Clark.

I remember well the day the Yankees acquired McCullers as part of a package for Clark. Reacting to the news with boyish fervor, I thought that the trade would help the Yankees on two fronts. With a 95 mile-an-hour fastball and a knee-bending slider, McCullers appeared to be the young relief ace who could effectively replace the erratic Dave Righetti. That, in turn, would have allowed the Yankees to put Righetti back in the starting rotation, thereby strengthening one of the weakest areas of the team.

For his part, McCullers was thrilled with the trade, which removed him from the shadow of a Hall of Famer. “Before I was supposed to be the next Goose,” he told Michael Kay of the New York Post. “Now I’ll have a chance to be myself.”

At first, the Yankees seemed to be gearing McCullers for the closer’s role and shifting Righetti to the rotation, where I felt he belonged. They stubbornly resisted the temptation to change Righetti’s role, instead announcing that McCullers would become his primary setup man in the bullpen. McCullers then compounded the problem by flopping in his first season in pinstripes. After having pitched remarkably well for three seasons in middle relief, McCullers did not take well to a similar role in the Bronx. His ERA rose by more than two runs, from 2.49 to 4.57, despite a reduced workload in 1989. Often unhittable in the National League, McCullers found hitters in the junior circuit to be far less impressed with his arsenal of riding fastballs and diving sliders.

The beginning of McCullers’ second season in New York resulted in a bit of improvement, but he was clearly not the dominant pitcher he had been in San Diego. For some reason, McCullers had become subject to the same strange pitching disease that had affected so many other Yankees veterans in recent years: Rick “Big Daddy” Reuschel, Rich Dotson, Eddie Lee Whitson, Rick Rhoden, and Steve “Rainbow” Trout, just to name nearly a half-dozen. After having had success elsewhere, they all pitched appreciably worse in New York. Of course, they were all older pitchers facing the possibility of decline in their thirties. But McCullers was very young, 24 at the time of the trade, and owned a power-packed body that seemed relatively impervious to injury. So what exactly was the problem?

It could be that McCullers simply logged too many innings for the Padres in the mid-1980s. Perhaps that took a toll. Then again, McCullers never went on the disabled list during his stay in New York and never complained about having a sore arm. Rather than try to find an answer to the McCullers mystery, the Yankees decided to include McCullers in a package for another hotly sought commodity. Enamored with the idea of obtaining a left-handed hitting catcher with power, the Yankees sent McCullers and pitcher Clay Parker to the Detroit Tigers for Matt Nokes. The trade left McCullers shaken and his wife in tears.

McCullers found no more long-term success in the Motor City than he had in New York. He pitched reasonably well in eight appearances for the Tigers, but then noticed that two of the fingers on his pitching hand had turned a “ghostly white.” A medical exam revealed a blood clot in his pitching shoulder, requiring surgery and costing him all of the 1991 season. The clot was similar to what would occur to David Cone later in his career, but he would eventually make a long-term comeback. McCullers was not as lucky. He made only five appearances for the Texas Rangers in 1992. By the end of that season, he was out of the major leagues. He then pitched the 1993 season for the Triple-A Calgary Cannons, but struggled badly.

McCullers also felt a twinge in his shoulder that season. A medical examination revealed a torn labrum. “It wasn’t in the cards anymore,” McCullers told sportswriter Tim Healey. At the age of 29, McCullers was done - but without regrets. A quiet and modest sort, he seems happy to follow the career of his son, who has a chance for the long-term success that eluded the father.

Aside from the late-career arm problems, I’ve often wondered what went wrong with McCullers. His fall from prominence began with the Yankees, when he was still healthy. Maybe it was that overload of innings with the Padres that did him harm. Or perhaps those twisted pitching mechanics, so evident on his Score card, help explain why McCullers faded so quickly after exhibiting the talent to be one of the game’s great closers.

Maybe the answer was in the baseball card all along.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame