- Home

- Our Stories

- Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox

Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox

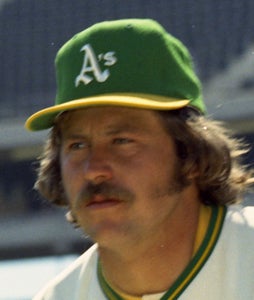

Forty years after his camera captured an historic baseball image, Doug McWilliams still remembers the early-evening radiance of the California sun.

“I always went to the Oakland Coliseum at 5:30 p.m.,” McWilliams said. “Always. The light was beautiful with flash fill.”

McWilliams, a veteran photographer for Topps, the baseball card company, was instructed by his employers to refrain from shooting players at night games, as they felt the images would not be as sharp.

But McWilliams, who was once hailed as one of “America’s best known sports photographers” opted to trust his instincts, which told him you could never tell when you’d be in position to get the perfect shot.

So McWilliams regularly showed up at night games, being sure to get there early.

His instincts were right.

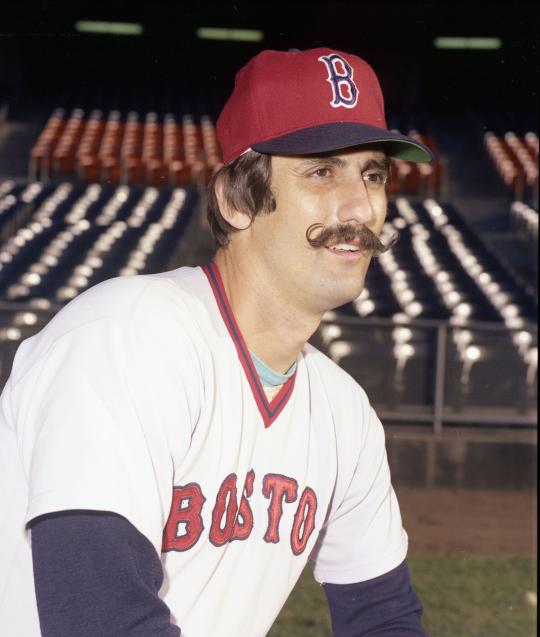

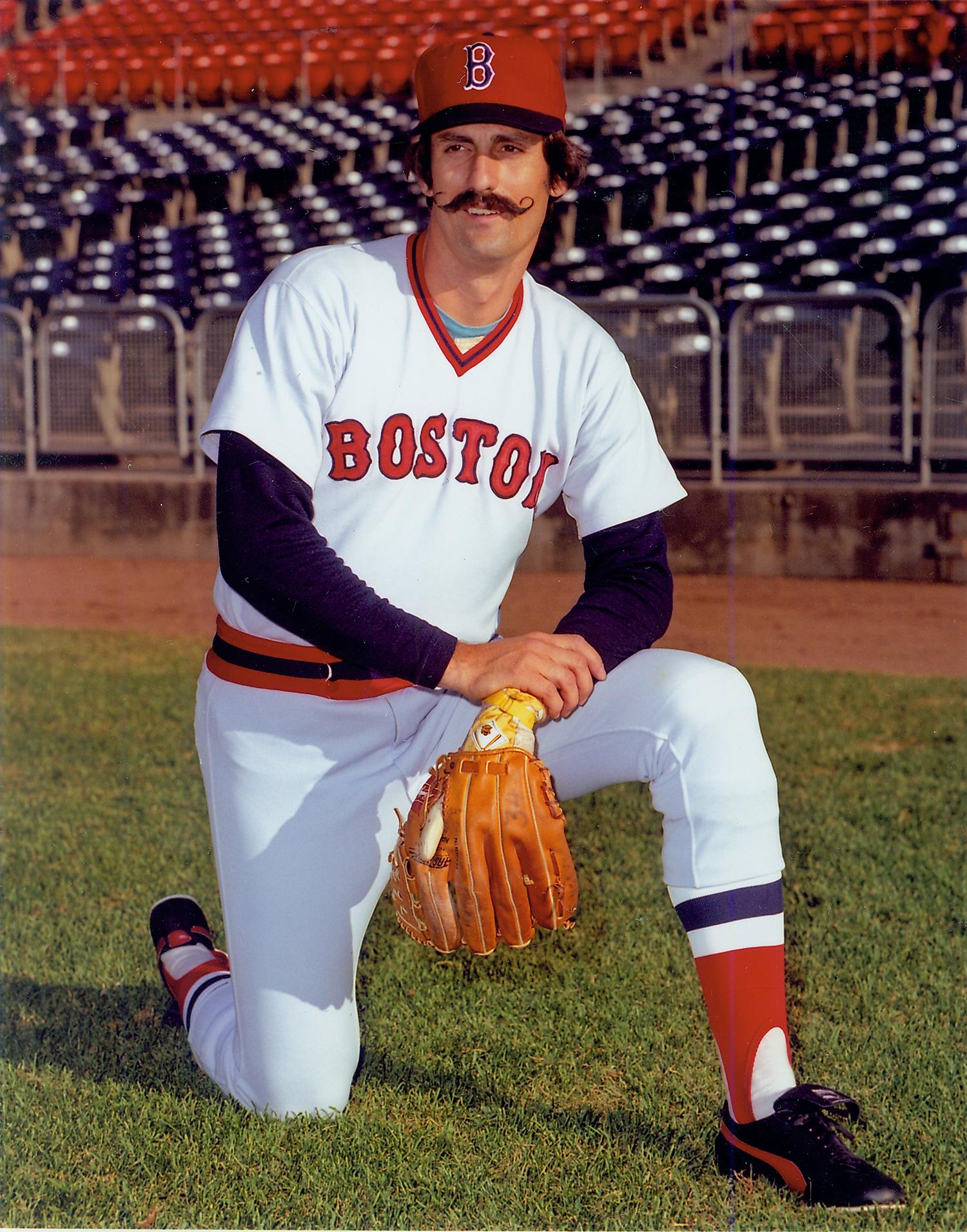

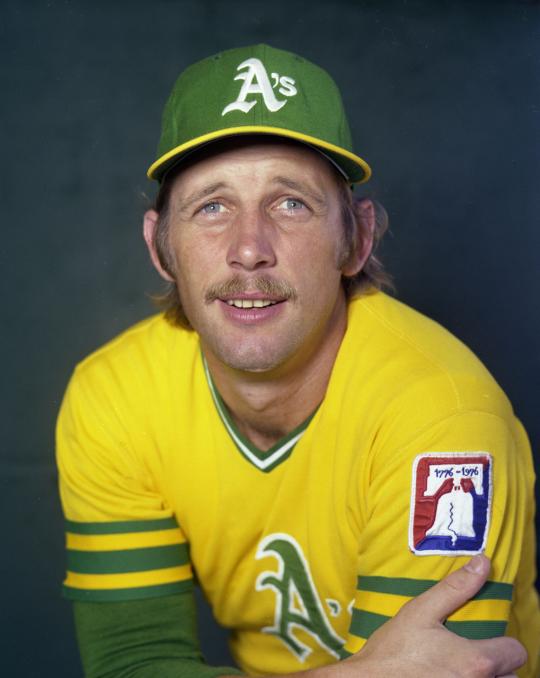

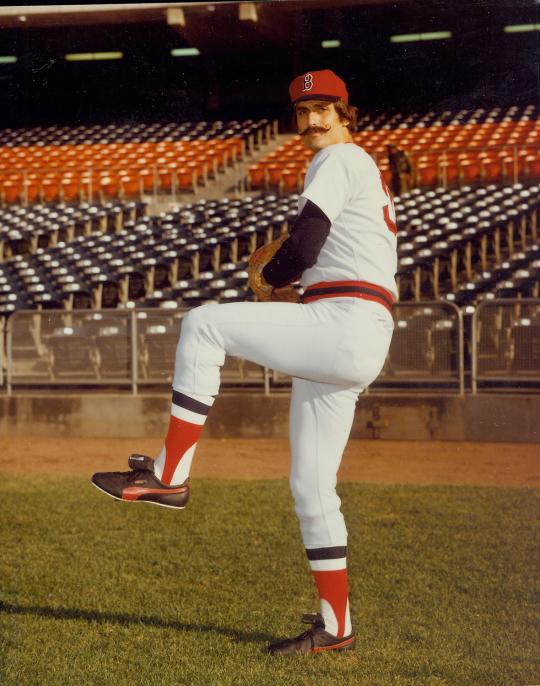

And the result was a photograph that remains the only one of its kind: A portrait of Hall of Fame relief pitcher Rollie Fingers, donning his brand-new Boston Red Sox road grays, during the first of three days he was a member of the organization.

The image – a startling reminder of perhaps the most hectic series of transactions in baseball's annals – never made it into mass production, yet would one day be preserved at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, part of the thousands of other negatives from McWilliams’ collection, all of which he generously donated to the Museum’s Photo Archive in 2010.

Decades after it was taken, McWilliams’ image still exudes the warm glow of tranquility, as the golden sunshine bathes the crimson and navy hues of Fingers’ new uniform and Fingers assumes a relaxed pose, kneeling in the Oakland grass.

But one thing the picture did not depict was the tension that had been rapidly rising to the surface within the Oakland Athletics’ organization in the hours previous to the photo – and the chaos that was about to unfold in the ensuing weeks.

On the evening of Tuesday, June 15, 1976, McWilliams arrived at the Coliseum as usual, just before 5:30 p.m., eager to capitalize on the lighting he so prized. It didn’t take long for him to realize something was different on this day.

“When I got inside the stadium, everyone was “buzzing” about a trade,” McWilliams remembered.

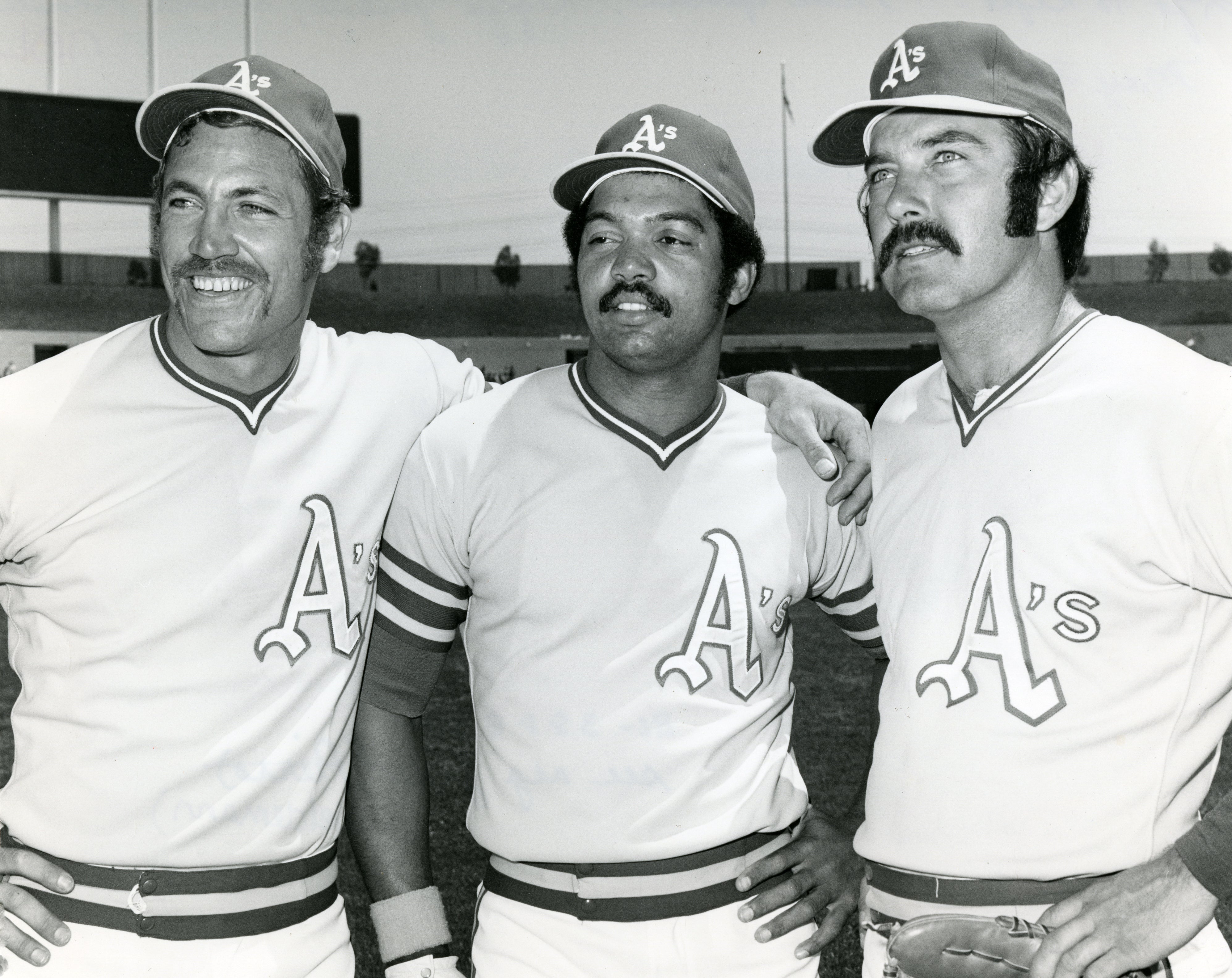

Just hours earlier, Oakland Athletics’ owner Charlie Finley had ripped the proverbial rug out from under Major League Baseball’s feet, by selling left fielder and first baseman Joe Rudi and relief pitcher Rollie Fingers to the Boston Red Sox for $1 million each, as well as Cy Young Award winner Vida Blue to the New York Yankees for $1.5 million. Since the Red Sox were in Oakland for a three-game series, Fingers and Rudi simply walked under the stands, over to the visitor clubhouse, and suited up – enabling McWilliams to capture the short-lived Red Sox career of Fingers.

The baseball world had not seen a sale of this magnitude since Connie Mack sold his star players from the championship-caliber Philadelphia Athletics in the early 1930s. Mack had dealt a plethora of future Hall of Famers, including Al Simmons, Mickey Cochrane and Lefty Grove, as a hedge against the onslaught of the Great Depression.

Sports Illustrated called Finley’s 1976 transactions the “biggest sale of human flesh in the history of sports,” and UPI called it the “Tuesday night massacre.”

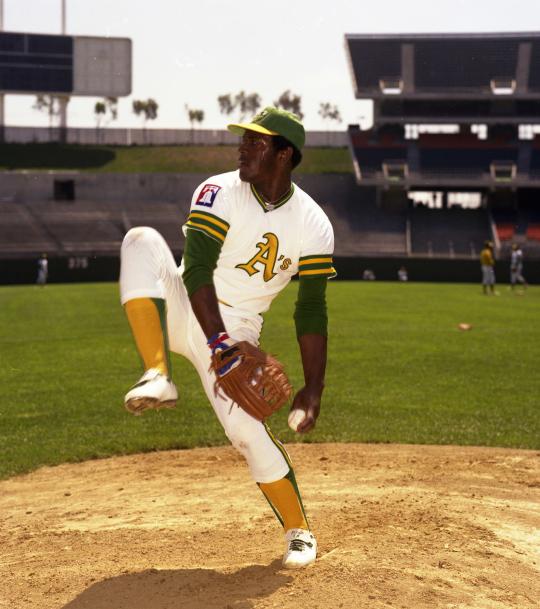

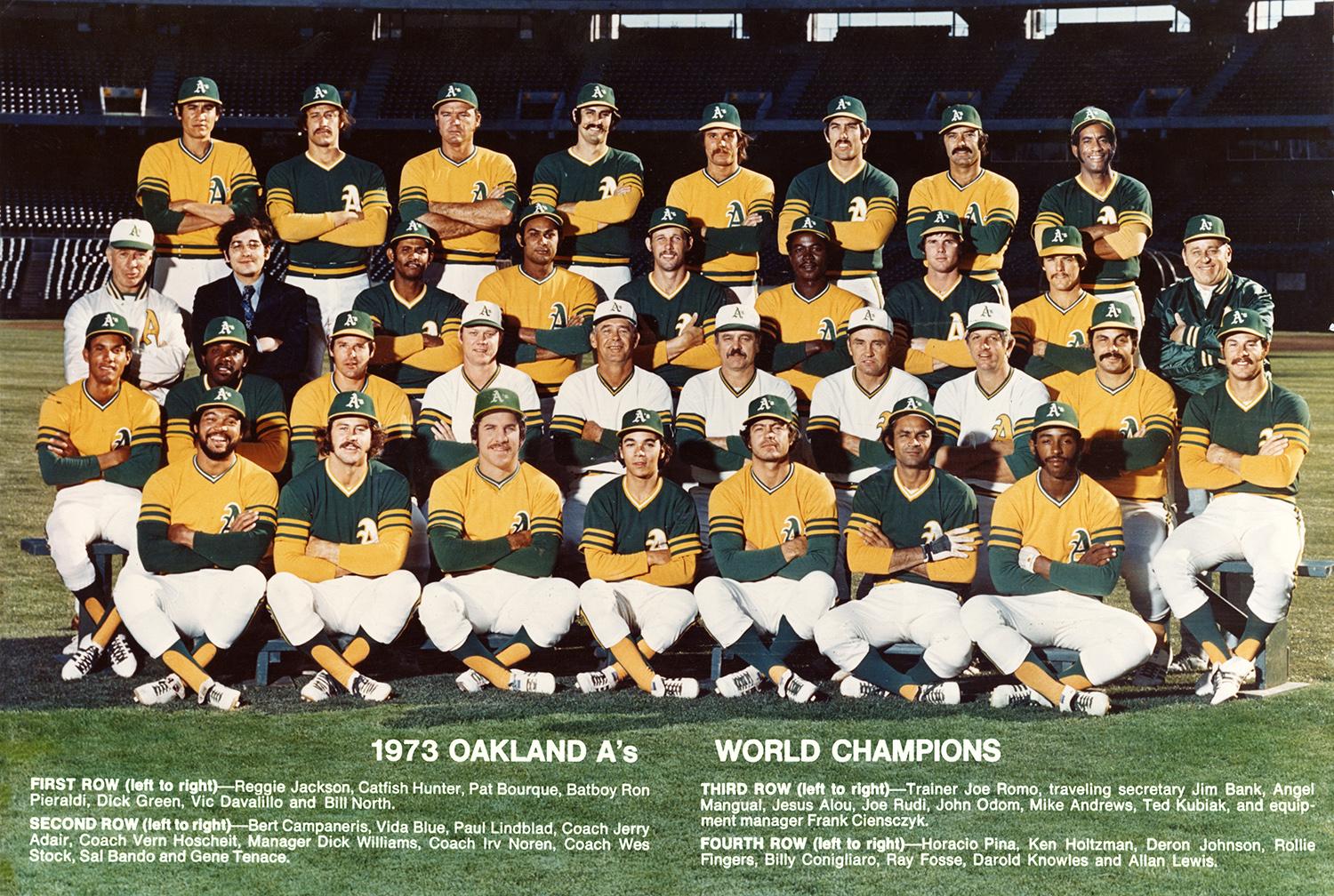

The shock that followed was understandable; the Oakland Athletics were the dominant team of the early 1970s. They had won their division title from 1971-1975, picking up three straight World Series wins along the way, in 1972, 1973, and 1974. Not unlike Mack’s Athletics, the 1970s-era Oakland A’s had their share of future Hall of Famers, among them Reggie Jackson, Catfish Hunter and Fingers, along with such stars as Blue, Rudi, Sal Bando and Bert Campaneris.

But Finley regarded himself as a profoundly savvy businessman, and with the sudden arrival of free agency, the negotiating tables were quickly turning in favor of the ballplayers – something that he would not stand for. Entering the 1976 season, six of his star players remained unsigned, which meant that they would soon be part of the first class of free agents in baseball history. This meant no profit for Finley – unless he sold them or traded them.

“Commissioner, I can’t sign these guys. They don’t want to play for ‘ol Charlie,” Finley would tell MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, in a meeting later that Tuesday evening, according to the biography Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball’s Super Showman. “They want to chase those big bucks in New York. If I sell them now, I can at least get something back. If I can’t, they walk out on me at the end of the season and I’ve got nothing. This free agency thing is terrible. The only way to beat it is with young players. That’s where I’ll put the money.”

Finley had already lost Hunter to free agency to the Yankees at the end of the 1974 season, after Major League Baseball ruled that Finley had not fulfilled clauses in his contract. Finley reacted by trading Reggie Jackson and Ken Holtzman to the Baltimore Orioles in the spring of 1976.

“When he traded [Reggie Jackson and Ken Holtzman] to Baltimore, we knew that it was the beginning of the end,” Rudi said to the Sporting News in 1977. “Most of us who were unsigned figured that, before the year was over, we were going to be traded. So we were all standing by, waiting for the hammer to fall.”

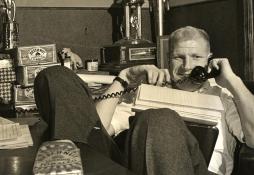

And the hammer did fall – hard – at 7:51 p.m. on that fateful Tuesday night in June of 1976, when the Associated Press started reporting that the three ballplayers had been sold from Oakland for cash to the Yankees and Red Sox. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn first caught wind of the deal while attending a White Sox vs. Orioles game in Comiskey Park, on hand to take in a showdown between Goose Gossage and Jim Palmer, but soon finding himself in a showdown of his own with Finley. Kuhn instantly contacted all teams involved and ‘froze’ the trade, until he made an official decision on the transaction.

Athletics Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

He decided to hold an Executive Committee meeting by phone the next day, weighing the input of multiple owners, but they were still unable to come to a decision, and remained deadlocked. Kuhn followed that meeting with another hearing, which included all of the parties involved: Charlie Finley, Dick O’Connell (the Red Sox's general manager), George Steinbrenner (owner of the Yankees), Gabe Paul (the Yankees' general manager), Marvin Miller (Executive Director of the Major League Baseball Players’ Association) and Finley’s attorney, David Kentoff. Ninety minutes later, the owners emerged from the meeting confident that the transaction would remain intact. According to the Sporting News, Finley had shown up in a bright golf shirt with a carnation tucked into the front pocket. Meanwhile, George Steinbrenner flashed a thumbs-up sign to the press while walking out of Kuhn’s office. Not traditional signs of defeat, one would conclude. “We’ll continue to play short three players until we decide on another avenue. Right now, we feel that Joe Rudi and Rollie Fingers are the property of the Red Sox and Vida Blue is the property of the Yankees,” Finley told the media. “We are certainly very confident that we will win this case because ballplayers have been sold since the beginning of baseball. The selling of ballplayers is nothing new.” But the plot thickened. On June 18, Bowie Kuhn shook the baseball world almost as hard as Finley had days before. He held a press conference telling the media that he was nullifying the trade, citing Article 1, Section 4 of the Major League Agreement, written in 1921, the era of baseball’s first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. The section gave the commissioner permission to take “steps as he may deem necessary and proper in the interest in the morale of the game.” Kuhn elaborated on his decision to rule against the sale, in his autobiography, Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner:

“If such transactions now and in the future were permitted, the door would be opened wide to the buying of success by the more affluent clubs, public suspicion would be aroused, traditional and sound methods of player development and acquisition would be undermined and our efforts to preserve the competitive balance would be greatly impaired.”

A commissioner had not exerted this degree of power since the time of Landis, after the Black Sox Scandal in 1919. The media largely sided with the Athletics’ owner, accusing Kuhn of over-stepping his boundaries as commissioner and exploiting the vaguely worded section of a document written more than 50 years prior to his decision. “With wording that vague, the power of the commissioner of baseball is, in effect, whatever the commissioner says it is,” wrote the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “The catch is that the owners hire the commissioner and have the power to fire him if they don’t like the action.” Red Smith, of the New York Times, labeled Kuhn “the most solicitous commissioner baseball has ever had.” The following week, Bowie’s face graced the cover of Sports Illustrated, under a headline which read: “Baseball in chaos: Bowie Kuhn jolts the system.”

And, of course, all of the teams involved had plenty to say about it too.

“I’m dumbfounded,” Yankees manager Billy Martin complained to Sports Illustrated. “This is worse than Watergate.”

Per usual, Charlie Finley's voice was the loudest of them all.

“Kuhn sounds like the village idiot,” he told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “It’s very stupid. There have been many, many cash transactions through the years and nothing has ever been questioned about those. You never know what to expect from Bowie Kuhn.”

A week after Kuhn nullified the trade, Finley decided to file a $10 million lawsuit in federal court against him, on the basis of ‘restraint of trade.’ For nearly two weeks, the Athletics’ owner refused to play Fingers, Rudi or Blue, insisting that they were property of the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees.

“If Charlie uses any of the players, then in essence he is ratifying the commissioner’s position,” asserted Charlie’s lawyer. “Also, what if the A’s play Rudi and he breaks a leg and then the court rules Rudi belongs to Boston. Who is to determine who will compensate Boston for the loss of Rudi?”

In Finley’s mind, it was all too risky. Unlike the Red Sox and the Yankees, who were in a tight pennant race, the A’s were struggling to finish above .500. So the incentive for him to utilize three star players and put $3.5 million on the line was basically nonexistent.

“I don’t even want them in uniform,” Finley told his manager, Chuck Tanner. “Also, keep them out of the clubhouse. Oakland players have been known to get hurt in there.”

Although Joe Rudi was also part of Charlie Finley's controversial sale to the Boston Red Sox that was eventually voided, Rudi would ultimately play for the team, in 1981. (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

When Kuhn realized that Finley wasn’t playing Rudi, Fingers or Blue, he directed the owner to use his players, stating that “this determination is contrary to the best interests of baseball and is inconsistent with the Oakland club’s obligation to give its best efforts to win games.” But Finley simply ignored Kuhn’s ruling, confident in his side of the argument.

While this was all going on, Rudi, Fingers and Blue were in complete limbo. Unsure of which club they were ‘officially’ affiliated with, they were forced to watch the hysteria between Kuhn and Finley unfold from the sidelines. Tanner had to make due with a 22-player roster for nearly two weeks. With every day that passed, the Oakland Athletics felt more and more enraged by the stubbornness of their owner – and finally decided to take matters into their own hands.

“We would come out to the ballpark, warm up, but we were not in uniform during the game,” Fingers recalled in an interview with the Hall of Fame. “And finally it got to the point where all the guys on the team saw how frustrated we were, and we had a team meeting. And we all voted – Minnesota had just come into town – that we’re not going to play the game against the Twins. We will forfeit it, and they will get the automatic win, unless Rudi, I and Vida were reinstated.”

Finley quickly heard of his team’s admirable exhibition of baseball frontier justice, and sought to quash it immediately.

“If they do strike, I just may go along and let them strike,” Finley told the Associated Press. “Don’t be surprised if there isn’t any ball game in Oakland tomorrow.”

He went one step further, threatening to replace his reigning world champions with the Tucson Toros of the Pacific Coast League, if they went through with it.

But the players called his bluff.

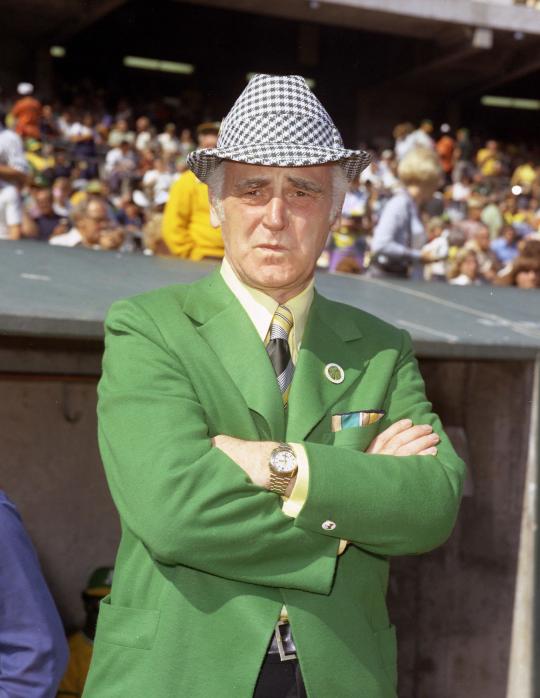

Almost immediately after Charlie Finley's controversial sale, then-Commissioner Bowie Kuhn nullified it, on the basis that it wasn't in the best interest of baseball. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

“The whole ball club was in the clubhouse 10 or 15 minutes before the game and we’re all in our street clothes. Nobody has taken batting practice, nobody has taken infield, we haven’t done nothing. We’re just sitting in the clubhouse waiting to see what is going to happen,” Rollie remembered. “And Chuck Tanner got on the phone with Charlie Finley and said ‘Hey Charlie, the boys aren’t going to play today, unless you reinstate them.”

“It continued until five minutes before the game, when Chuck came out of his office and started reading his lineup card: Bert Campaneris… Billy North… Joe Rudi – and as soon as he hit Joe Rudi, everyone ran to change into their uniforms. Kuhn wasn’t going to do anything. The only way we were going to get back in was by pressuring Charlie. And the only way to pressure Charlie would be by taking money out of his pocket. And forfeiting a game to Kansas City would’ve taken money out of his pocket.”

Third baseman Sal Bando backed up Fingers’ recollection of the protest, saying that once Rudi’s name was called, it was “mass hysteria.”

“It was like the World Series around here,” he recalled to the Sporting News. “All we wanted to hear was that Rudi’s name was in there.”

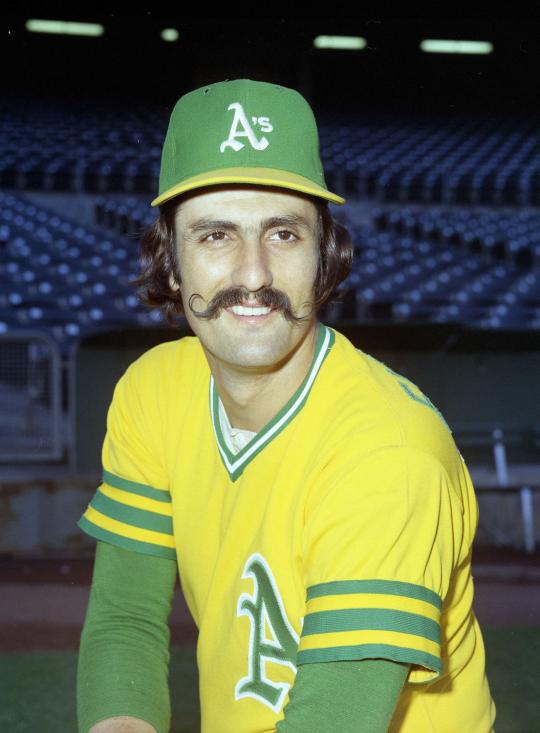

While Rudi would go hitless in that game, Fingers pitched three and a third innings to earn his ninth save of the 1976 season – on his way to a final tally of 341. The Athletics would finish with a record of 87-74 that year, finishing 2.5 games behind the American League West champion Kansas City Royals. “I think if we had had the opportunity to play those two weeks, we would have won the pennant that year,” Fingers said to the Sporting News. But by the end of 1976, he and his fellow free-agent teammates were eager to put the Finley era behind them. “Charlie Finley thought he was right, Bowie Kuhn thought he was right, and we were kind of just stuck in the middle,” Fingers said. “When I first found out [about the sale] I was happy to be away from Charlie. He was a pain in the neck – the only guy to not put a diamond in a World Series ring, the cheapest owner in the world. We won three straight world championships for him, and he wouldn’t do anything to make life easy for us.” Joe Rudi was more emotional, crying in the Oakland clubhouse, when he had heard the news he would be traded to the Red Sox. “We were ecstatic to be going to Boston. My wife had the whole house packed the next day,” he was quoted as saying in Charlie Finley. “But it was still an emotional day. I was an ‘A’ my whole life, and all of a sudden I’m on the Red Sox side.” Rudi would finally play for the Red Sox in 1981, after a five-player exchange that saw him dealt from the California Angels for Fred Lynn. In November of 1976, Charlie Finley’s attempt to outsmart free agency finally caught up with him, as his six star A’s players re-entered into the new free agent draft, and his franchise crumbled before his eyes. Don Baylor and Joe Rudi went to the Angels, Fingers and Gene Tenace to the San Diego Padres, Sal Bando to Milwaukee and Bert Campaneris to the Texas Rangers. Finley did not take it well. “It’s horse manure,” he told the Associated Press. “It’s the worst thing that has ever happened to baseball – it’s the worst thing that could ever happen to baseball. It reminded me of a den of thieves – everybody out to cut each other’s throats. We spend millions developing these players. We give them a bonus. We nurse them through the minors. We develop them at a great expense over a period of maybe 10 or 12 years. Then, bang! Just like that, they are taken away.” Rollie would go on to win a Cy Young Award and an MVP award in 1981 with the Brewers, and 17 years after he first suited up for the Oakland A’s, would leave baseball with the record for most career saves, three World Series titles, and in 1992, a Hall of Fame induction. “[After being inducted] I yakked to Carl [Yastrzemski] about it once – when I was a Red Sox our lockers were right next to each other,” Fingers says. “I mentioned it to Carlton Fisk once too. The guys took me and Rudi in like one of their own.” Forty years after it was taken, Doug McWilliams’ portrait of Rollie Fingers still emanates purity, amidst the impending legal battles and turbulent trade negotiations. He’s staring straight into the sun, almost as if he’s looking toward the next stage in his career. Complications and feuds aside, the bottom line was that Fingers wanted to be able to play the game he had devoted his life to. “I don’t care where I go,” Fingers would say to the Associated Press, moments after he’d heard he would be returning to Oakland. “I just want to play. Oakland, Boston – it doesn’t make a difference. I’ll play baseball anywhere.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame