“I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Keep Baseball Going

Keep Baseball Going

Baseball executives all over the country were worried. The fate of the game had been in the hands of the United States government once before, and it had not gone well.

More than 20 years earlier, when young men were drafted to fight in World War I, the government deemed baseball, and other sports, to be non-essential activities. General Enoch Crowder issued a “work or fight” order on July 21, 1918, which required men with non-essential occupations, such as ballplayers, to get a war-related job or be drafted into the military. Despite pleas for compromise from baseball executives, war-time responsibilities forced an early close to the season on Sept. 2, 1918.

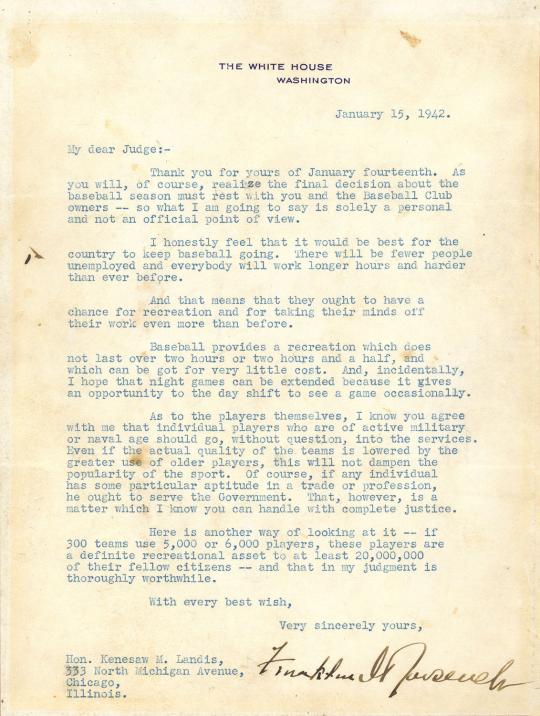

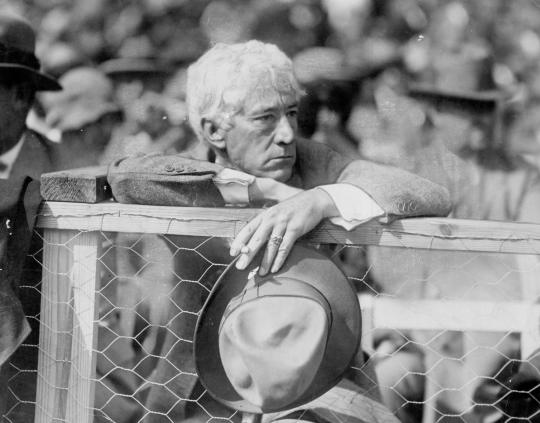

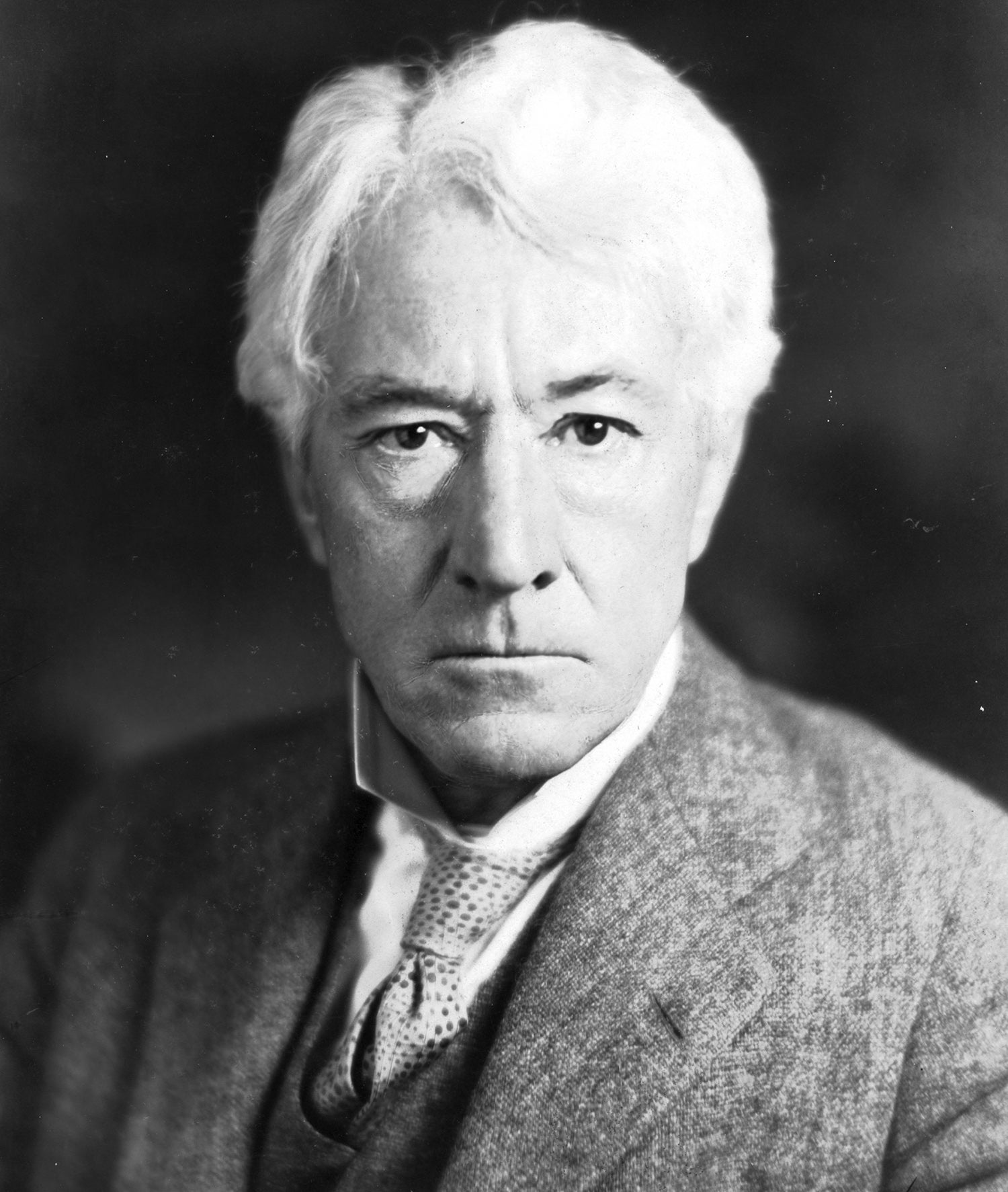

Now it was 1942, just a month after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, and baseball owners didn’t know if they should start planning for next season. They were unsure about baseball’s place in wartime America and, after much debate amongst themselves, they convinced Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis to take the matter to the president. Landis was a staunch Republican and his distaste for the politics of Democrats, including President Franklin Roosevelt, was well documented. But on Jan. 14, 1942, he sent a handwritten letter to the White House asking for the president’s advice. Landis wrote, “The time is approaching when, in ordinary conditions, our teams would be heading for spring training camps. However, inasmuch as these are not ordinary times, I venture to ask what you have in mind as to whether professional baseball should continue to operate.”

President Roosevelt responded quickly, writing to Landis the next day. In what has become known as the “Green Light Letter,” Roosevelt said, “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.” Roosevelt stated that baseball could be a source of relaxation for American workers, whose hard work and well-being would be essential to victory. He continued to explain that, “Baseball provides a recreation which does not last over two hours or two hours and a half, and which can be got for very little cost. And, incidentally, I hope that night games can be extended because it gives an opportunity to the day shift to see a game occasionally.” The value of baseball was in its ability to benefit so many while requiring so few resources, said Roosevelt, and combining the number of minor and major league teams he added, “If 300 teams use 5,000 or 6,000 players, these players are a definite recreational asset to at least 20,000,000 of their fellow citizens – and that in my judgment is totally worthwhile.”

President Roosevelt made it clear that although he wished for baseball to continue, he would not exempt players from military service if they were eligible. Aware that there were concerns that baseball’s popularity would diminish when star players left to serve overseas, Roosevelt had faith that, “Even if the actual quality of the teams is lowered by greater use of older players, this will not dampen the popularity of the sport.” He emphasized that this was his personal opinion and that the official decision should be left to Landis and the club owners.

“Baseball feels highly honored that Mr. Roosevelt has chosen to regard our game as such a vital asset to popular morale.”

The president’s Green Light Letter was front page news all over the country, with headlines reading “Stay in There and Pitch: FDR” and “President Says U.S. Needs Its Baseball.” Fans, players, and owners applauded the president and breathed a collective sigh of relief. Clark Griffith, president of the Washington Senators, said, “Baseball feels highly honored that Mr. Roosevelt has chosen to regard our game as such a vital asset to popular morale.” And Larry MacPhail of the Brooklyn Dodgers told the Chicago Sun-Times, “President Roosevelt’s letter has clarified the entire baseball picture. The needs of the government are paramount, but I believe baseball can contribute a lot in these times.”

Some still questioned the safety of organizing large sporting events during a period of war and pointed to Roosevelt’s request for more night games as a potential danger. Joseph A. Sasso, a baseball fan from Philadelphia, wrote to the commissioner expressing a concern that the bright lights used during night games, “may tip off enemy bombers of that fact and they could plan their destruction accordingly.” In general, though, fans were excited for the continuation of baseball. Sid Keener, sports editor at the St. Louis Star-Times, wrote an open letter to Landis and the presidents of the American League, National League, and National Association of Minor Leagues on January 30, 1942, asking them to organize a “President Roosevelt Night” at every professional ballpark in the country. Keener believed it would be a fitting way to show baseball’s appreciation, but it would also be a chance for them to raise money for organizations like the Red Cross or Navy Relief Fund.

In the months and years that followed the Green Light Letter, others echoed Keener’s ideas and a few wished to take it a step further. J.G. Taylor Spink, publisher of the Sporting News, printed a letter in 1945 calling for the induction of President Roosevelt into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Spink argued, “…that but for his support, encouragement, and active espousal of the game in Washington, professional baseball would have been shut down as early as the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor…[without] Franklin Roosevelt, you would have had no baseball these past four seasons.”

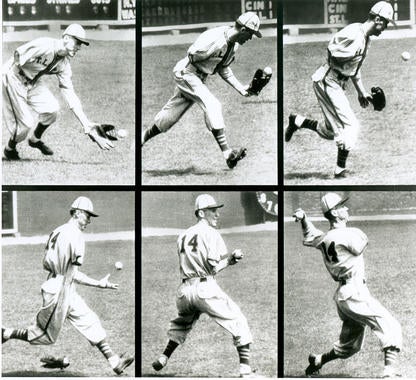

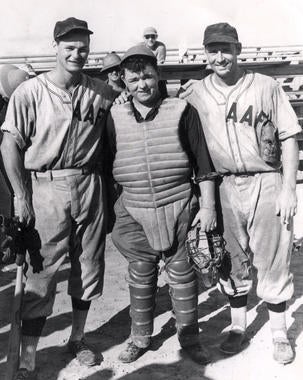

During those four war-time seasons, 1942 to 1945, many major leaguers joined the armed services. Some, like Hall of Famer Bob Feller saw combat. Others were assigned non-combat duties and were able to play on military baseball teams.

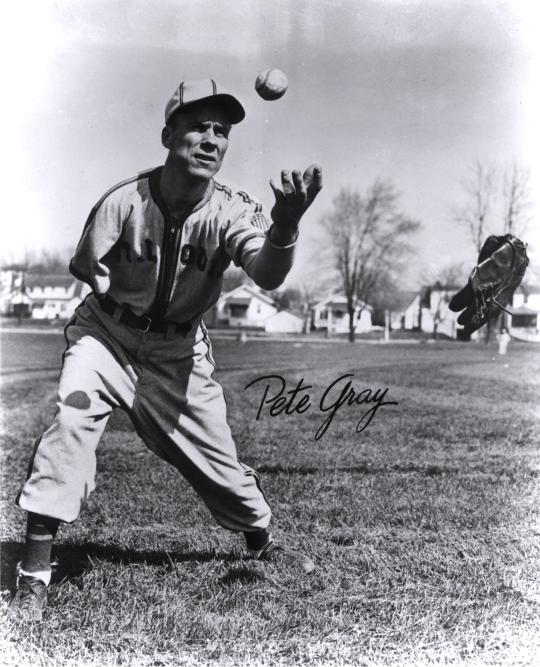

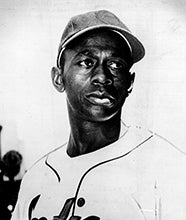

In their absence, rosters became dotted with an unusual collection of players, such as Pete Gray, the one-armed outfielder who batted .333 for the Southern Association in 1944, earning MVP honors, and played 77 major league games for the St. Louis Browns in 1945. Many veterans came back to give baseball another go and some younger players, like 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall of the Cincinnati Reds, got a shot at baseball glory at an early age. But the need for players did not push owners towards integration, and black players continued to be shut out of the major leagues. Hall of Famer Satchel Paige spent the war years playing in the Negro Leagues, while white players of considerably less talent signed big league contracts.

An interesting period of history would be missing from the record books had it not been for the president’s letter. The St. Louis Browns, known for being perennial losers, went to the 1944 World Series, their only appearance in franchise history. And although the Chicago Cubs won the 1945 National League Pennant, most Cubs fans today wish that the season had been canceled due to the “Curse of the Billy Goat”. During Game Four of the 1945 World Series, local tavern owner Billy Sianis was forced to leave Wrigley Field because he had brought a goat with him to the game. As he was being ushered out, Sianis is reported to have said, “The Cubs, they ain’t gonna win no more,” and the curse was born.

Baseball historians agree that Roosevelt’s Green Light Letter had a profound impact on the game. It encouraged baseball executives to continue the game, giving millions of Americans a recreational outlet, while also granting thousands of others a chance to take the field and serve their country with a bat and ball instead of a rifle. It helped baseball remain the National Pastime by keeping it in the public eye and allowing a new generation to be exposed to the sport. For that reason, the Green Light Letter is considered one of the most important documents in baseball.

The original letter is currently in the archives at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, along with more than million other documents.

Matt Cox was a curatorial intern in the 2009 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Leadership Development