- Home

- Our Stories

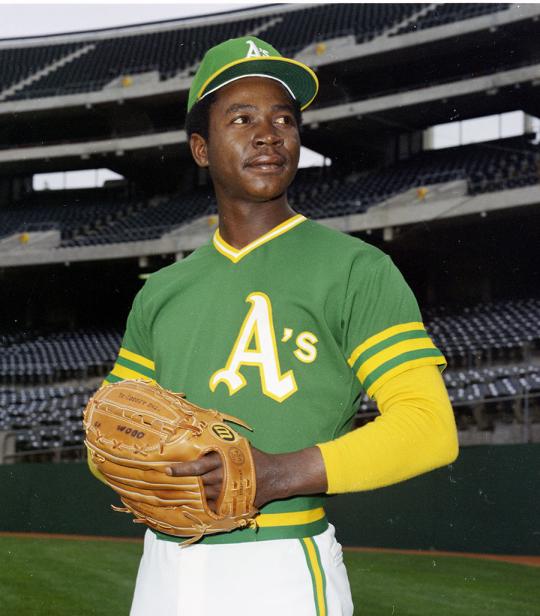

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Blue Moon Odom

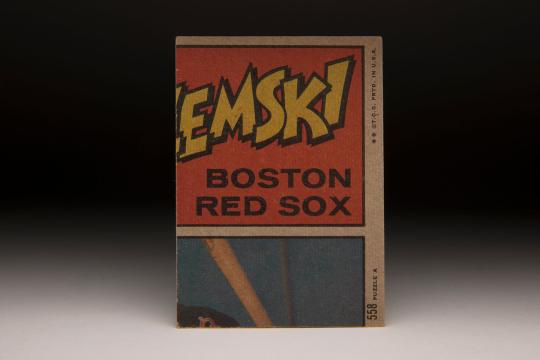

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Blue Moon Odom

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Every once in a while, an old card set from the Topps Company makes news today, as it did in a recent article by Paul Lukas, the author of the popular “Uni Watch Blog.” Lukas’ column usually puts the spotlight on uniforms and equipment, but he recently devoted some space to writing about the 1972 Topps “In Action” series.

Lukas highlighted some of the odd and interesting choices in the action subset, including the following: a photo of Tom Seaver, with his hands on knees, apparently yelling at an umpire; an obstructed view shot of Ron Santo, who is partially blocked by a San Francisco Giants catcher at Candlestick Park; Roberto Clemente rolling his eyes and head in disgust at a called strike; Ed “Spanky” Kirkpatrick shaking dirt out of his catcher’s mask; Bob Barton staring forlornly through a wire fence after running out of room on a foul pop-up; and Billy Martin engaged in - what else? - an argument with an umpire. None of these is likely to be regarded as classic baseball action, though they do bring some amusement all these years later.

At the time, Topps had barely started venturing into the realm of action shots on baseball cards. Topps had introduced action shots only one year earlier, as part of its memorable black-bordered set of 1971. Realizing that it had something good with these action shots, which especially appealed to kids, Topps decided to highlight its action cards in the 1972, with a bright red frame and the words “In Action” printed at the top of each card.

In the early 1970s, Topps had a limited library of action shots, so it put out what it had in terms of photographs from actual games. Topps managed to assemble 72 photographs that it felt were suitable for the “In Action” series. Some of the players were stars, like the aforementioned Clemente and Seaver and Santo, along with other legends like Johnny Bench, Harmon Killebrew, and Willie Stargell, but some were journeymen, everyone from Barton to Curt Blefary to Jerry Johnson. When it came to action cards, all were welcome, even backup catchers and long relievers.

As a young fan at the time - in fact, 1972 marked my first year of collecting - I couldn’t have cared less whether the players were stars or not, or whether the “action” was legitimate, hokey, or plain ridiculous. I loved these action cards; in fact, I still do. At the time, all other cards typically showed players posed on the sidelines, or up close and personal as portraits. The action cards were something different, something lively, and represented the actual game itself. For me, there was nothing better than having a baseball card that showed a player plying his trade in a real-life major league game.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

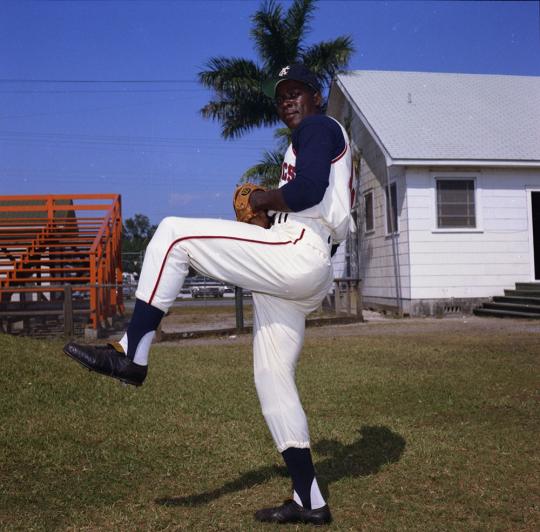

Of all the 1972 action cards, one of my favorites is the John Odom card. Like the Seaver and Vida Blue cards, it gives us a non-traditional look on the pitcher’s mound. Having just completed his delivery, Odom appears to be off balance, his weight fully on his left leg, while his right leg kicks awkwardly into the air. Odom looks like he’s about to go into full cartwheel mode, adding an element of comedy to the card. While Odom certainly appears funny and ungainly here, the photo does remind me of his pitching style. I remember him having a weird follow-through, to the point that he finished his delivery out of whack, seemingly standing on one leg.

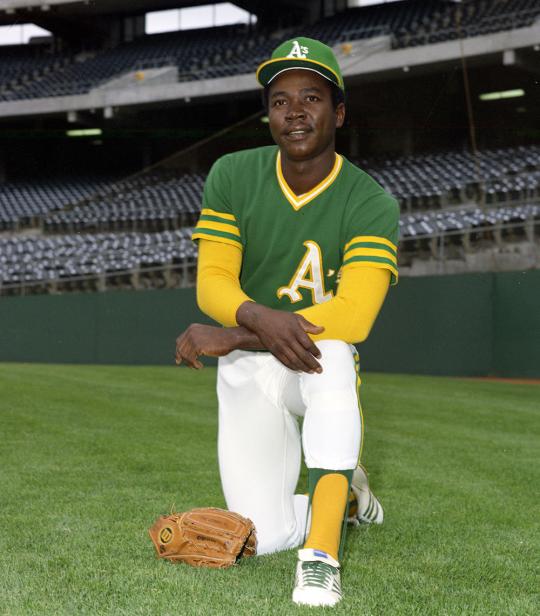

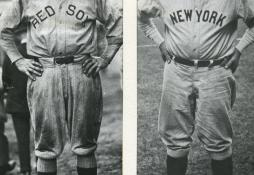

Two other features of the Odom card stand out. First, we should note that Odom is wearing the Oakland A’s’ old-style sleeveless uniform, with a white vest against a green undershirt. The photo must have been taken during the 1971 season, the last year the A’s featured the sleeveless look. By 1972, the A’s had switched to their famous polyester pullovers, alternating jersey colors between California gold, Kelly green, and Polar Bear white—as owner Charlie Finley liked to call them.

Second, the card lists the veteran A’s right-hander as John Odom, even though most fans and members of the media called him “Blue Moon” - and still do. For some reason, Topps tended to stay away from using nicknames on cards, even when nicknames superseded the player’s given name in popularity. It’s still a great card, but it would have been that much better with the colorful name of Blue Moon attached to it.

Odom’s nickname has long been one of the game’s favorites. The origins of the nickname go back to his days in elementary school. One of his friends, a schoolmate named Joe Morris, noticed Odom’s round face and thought it looked like the moon. So he began calling him Blue Moon, and the nickname stuck to him like pine tar.

Blessed with a great nickname and a live right arm, Odom quickly drew the attention of major league scouts while pitching high school ball in Macon, Ga. One of those scouts was Jack Sanford, a former big league first baseman who was then working as a scout for the Kansas City A’s. It was 1964, the last year that high school and college players were essentially free agents and not subjected to a draft by Major League Baseball. Sanford told his boss, A’s owner Charlie Finley, that he needed to sign the vastly talented Odom.

After Finley dispatched minor league manager Haywood Sullivan to watch Odom in person, the owner decided to recruit the young right-hander himself. He arranged for a truckload of food to be sent to the Odom house, where Finley met the family and then proceeded to cook dinner for them!

Overwhelmed by Finley’s face-to-face approach, Odom and his family agreed to sign with the A’s. Odom accepted a bonus of $75,000 and received an assignment to the Birmingham Barons, Kansas City’s Double-A affiliate in the prestigious Southern League.

As much talent as Odom possessed, he wasn’t fully ready for the Jim Crow-level of segregation that would face him in the Southern League in 1964. Shortly after signing with the A’s, Odom was driving a new car that he had purchased with his bonus money through downtown Birmingham. A local police officer, apparently questioning how a young black man could own such an expensive car, pulled Odom over. Odom had done nothing wrong, but that didn’t stop the officer from scolding the rookie pitcher and then telling him he would let him off with a warning. The policeman then advised Odom that he should he keep to the black section of Birmingham, though the words he used were far more vitriolic than that.

Given such unfair treatment, it’s understandable why Odom struggled in his first few starts with Birmingham. Over his first 16 games, Odom put up mediocre numbers, but Finley was determined to rush him to Kansas City. On Sept. 5, Odom made his major league debut for the A’s. He would pitch poorly in five starts, showing little command or control of his pitches.

Over each of the next three seasons, Odom split his time between the majors and the minors, as he struggled to harness his control. He finally seemed to arrive for good in 1968, by which time the A’s had moved to Oakland. He won 16 games, logged 231 innings, and put up an ERA of 2.45. Certainly, he was aided by the conditions that existed in the Year of the Pitcher, but he also made his first All-Star team and emerged as arguably the most effective pitcher on Oakland’s staff.

Odom continued to pitch well in 1969, a year that saw him make the cover of the Sporting News, but ran into trouble the following summer. With his walks (100) outnumbering his strikeouts (88), there was an indication that something might be wrong. There was; after the season, he underwent surgery to remove a large bone chip from his right elbow.

Recovering from the surgery, Odom missed all of Spring Training and the first six weeks of the regular season. His velocity diminished, he struck out only 69 batters in 1971, with his walks again exceeding his strikeouts. Even though the A’s won the American League West title, they opted to keep Odom off the postseason roster.

Odom’s arm trouble forced him to become a better pitcher, and less reliant on simply throwing with power. Becoming more adept at the art of pitching and equipped with a more deceptive motion, Odom pitched beautifully in 1972, the year of his memorable action card. He won 15 of 21 decisions while putting up an ERA of 2.50, and earned a few votes in the Comeback Player of the Year balloting.

In contrast to 1971, Odom showed enough arm strength to make Oakland’s postseason roster. It was during the American League Championship Series that Odom made headlines, but not just for pitching. In a decisive Game 5 against the Detroit Tigers, Odom pitched well through five innings, but labored with his breathing and left the game early. In the postgame clubhouse, Vida Blue joked that Odom had “choked,” which nearly fueled a fistfight between the two teammates.

That controversy became forgotten when the A’s went on to win the World Series, pulling off an upset of Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine.” Although Odom took a loss in the Series and made the last out of another game as a pinch-runner, trying to score on a short pop-up to Joe Morgan, he pitched creditably in each of two starts. The A’s won their first championship since the franchise’s days in Philadelphia.

That season turned out to be Odom’s last good year wearing the green and gold. His performance slipped in 1973 and ’74, as he continued to struggle with his pitching health. He also battled his temper, a problem that cropped up periodically during his career. On the eve of Game 1 of the 1974 World Series, Odom brawled with teammate Rollie Fingers, shoving the ace reliever into a locker. The fracas resulted in a twisted ankle for Odom, though it didn’t seem to affect his performance in two relief outings against the Los Angeles Dodgers. Finally, a bad start to the 1975 season doomed Odom in Oakland. On May 20, the A’s sent Odom out of town, trading him to the Cleveland Indians for veteran right-handers Dick Bosman and Jim Perry.

Odom reacted enthusiastically to the trade, expressing a desire to play for the game’s first black manager, Frank Robinson. But Odom made only three appearances for the Indians before being traded a second time, this time at the June 15 trading deadline. Sent to the Atlanta Braves for journeyman catcher Pete Varney, Odom would find himself in disastrous straits in the National League. He lost seven of eight decisions with the Braves and saw his ERA balloon to 7.71. The following June, the Braves dealt him to the White Sox, where he enjoyed one more moment of glory, pitching a combined no-hitter with Francisco Barrios, before drawing his release in January of 1977.

Still only 31, Odom found no takers in the major leagues. So he sought refuge in the Mexican League, where he pitched for two seasons. During the 1977 season, Odom pitched with such indifference in one game, merely lobbing the ball over the plate, that the Mexico City Tigers suspended him for a “lack of professionalism.” One year later, Odom’s playing days came to an end.

While some players make a smooth transition to life after baseball, Odom did not. He became involved with drugs, especially cocaine. In May of 1985, he tried to sell cocaine to one of his co-workers. Odom lost his job and faced criminal charges. With the possibility of prison looming over him, a depressed Odom drank so heavily one night that he threatened his wife with a shotgun and then locked himself in his apartment, creating a six-hour standoff with police. It took tear gas to finally force Odom to come out of the apartment and surrender himself to authorities.

Odom would spend 55 days in jail on the charge of selling cocaine. For a player who had been part of three World Championship teams with the A’s, Odom had hit the bottom.

Frankly, it would not have been shocking to hear that Odom had ended up back in prison, homeless, or dead. His life could have ended in dire circumstances. To his full credit, Odom realized that he needed to change. He entered into alcohol rehabilitation, spending six weeks there. He stopped using drugs, and stopped drinking and smoking.

By 2013, Odom’s turnaround became fully publicized through the release of a wonderful new book, Southern League, by Larry Colton. A former minor league and major league pitcher, Colton examined the racial difficulties faced by Odom and the other members of the 1964 Birmingham Barons, who essentially integrated the Southern League despite Birmingham’s long history of racial intolerance. In writing the book, Colton became good friends with Odom, as he learned about the transformation of a retired pitcher who had once seemed on the brink of extinction.

“He’s doing great now,” Colton told me in 2013. “He’s one of the real joys of doing this book. I was worried about him going in. He had a reputation for being sullen. He’s living in Southern California, so I went down to see him. [At first] he was very guarded. He didn’t want to talk about the problems with the police.

“But now he’s been clean and sober for 20 years. He didn’t make much money comparatively during his career, but he has a good pension and manages to get by. He loves to play golf. We played several rounds of golf together. He was leery at first, but we met several times, and with each progressive meeting, we connected a little more. At one point, he said, “You’re fun to be around.” And then later, he said, ‘I think you’re one of my best friends now.’ ”

At one time, Odom was as off balance in his personal life as he appeared to be on his 1972 “In Action” card. Odom is now right-side up, further proof that the game always has room for the man willing to redeem himself.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame