"This is his own words, the last words perhaps, in many ways that I am aware of. That’s significant."

- Home

- Our Stories

- Jackie’s own words

Jackie’s own words

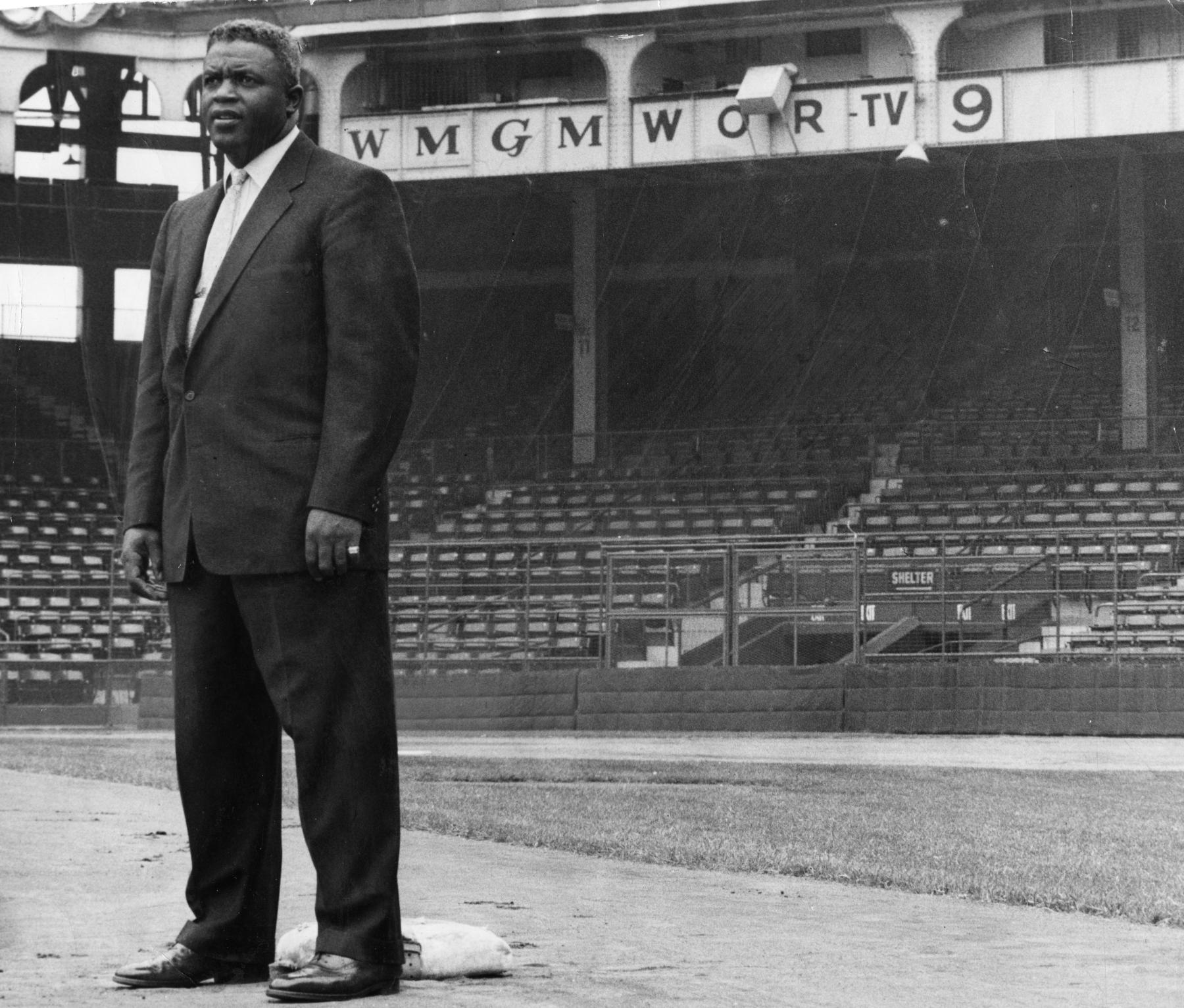

By September 1972, the effects of diabetes were ravaging Jackie Robinson’s once-athletic body. Nearly 16 years removed from the end of his career in Major League Baseball, Robinson’s body may have slowed, but his mind and his intellect remained as sharp as ever. This was evident during his speech to a construction trade group at the old Granit Hotel – now known as the Hudson Valley Resort and Spa – in Kerhonkson, New York, a town tucked into the Shawangunk Mountains, about 100 miles north of New York City.

No one – not even Robinson himself – could have known he was a mere 34 days from passing away.

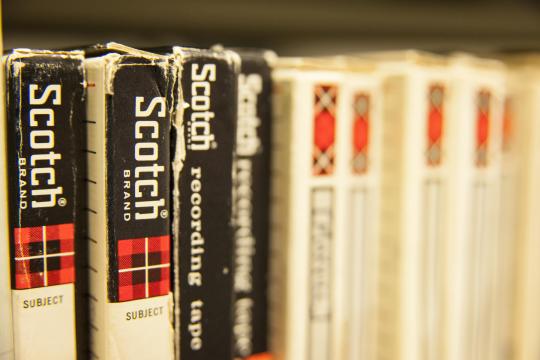

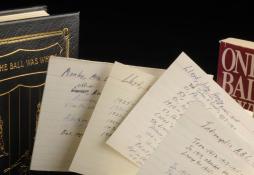

Al Lonstein, however, attended that speech and later performed a nine-and-a-half-minute interview with Robinson, which may be the final lengthy interview in Robinson’s life. The audio cassette tape with that recording has now found its way to the archives of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, thanks to Lonstein’s son Wayne, an attorney in upstate Ellenville, N.Y.

The elder Lonstein was born in Brooklyn and raised in the Bronx, though he remained true to the Dodgers growing up, Wayne Lonstein said.

“He was a huge Dodger and a huge Jackie fan, so when he had the opportunity for his show, to conduct interviews, he would travel to wherever, including to the (Baseball) Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony,” Wayne Lonstein noted. “He would get press credentials and go up there and interview the old Hall of Famers as well.”

Wayne Lonstein also remembered on those trips that they would “lick stamps all night at the Cooperstown Campground and then take them to the post office on Hall of Fame Induction Day to have them cancelled that day.”

Though a lawyer by trade, Al Lonstein’s loves were baseball and big band music. His “avocation of love,” according to his son, was his radio show called “The Make Believe Ballroom,” which aired on WELV, a local station in Ellenville. His interest in music, particularly in Frank Sinatra, led him to write The Revised Complete Sinatra, which is considered Sinatra’s definitive discography.

From Ol’ Blue Eyes to Dodger Blue, Al Lonstein desire to interview former ballplayers and other personalities led him to Kerhonkson in the waning weeks of Robinson’s life. The recording, almost 15 minutes in total, also features the last few minutes of Robinson’s speech to the conference attendees. For Wayne Lonstein, the significance of Robinson to American history and his father’s love of the game made Cooperstown the natural recipient of the cassette tape.

“I think it is of significance historically in the world of Jackie Robinson – the movie (42) was great, there have been so many things – but the toll this man paid can never be fully understood in an hour or two hours,” Wayne Lonstein explained. “This isn’t somebody’s artistic representation of what Jackie did or said. This is his own words, the last words perhaps, in many ways that I am aware of. That’s significant.

“You know, maybe I could sell it. Maybe it’s got some value. I didn’t want to exploit it because my father’s love of the game and importance that he placed on the institution outweighs that. I’d rather that his name be associated with the Hall of Fame than a dollar bill be put on it. Honestly, that’s honoring somebody else’s wishes. … A lot of it is Jackie’s own words. I don’t think that anybody has the rights to that other than a place where other people can access it. I think that’s important. I think we loses that in today’s world. People should have access.”

Accessibility to the game of baseball was something on Al Lonstein’s mind for many years, starting during a brief time he spent in the south, as talented African-American ballplayers faced the color barrier and were unable to play alongside whites.

“He said that if this was just the population of the white world, imagine how deep that bench is in the Negro Leagues,” Wayne Lonstein recalled, referring to his father’s view of the quantity of baseball talent among the races. “This is what half of it looks like. Imagine what it looks like when this comes together.”

This sense of bringing people together through baseball carried over to Al Lonstein’s life in Ellenville, where he was a major factor in the development of the town’s Little League programs and helped build the baseball fields. Many individuals continue to tell Wayne Lonstein about the impact his father, who passed away in 1993, had on their lives. Some of them came from lesser means and might not have been able to ordinarily afford the trip to a ballgame. It was Al Lonstein who came by, picked the kids up, and took them to a Mets or a Yankees game.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“He said there is no excuse for a kid not to go (to a ballgame),” Wayne Lonstein said. “He did it because it was his love of baseball, and (baseball was) a vehicle to achieve a more complete union in this country.”

In 1972, however, the country was facing serious levels of discord from a number of avenues: Political, social, economic, and others. Those themes related to some of the topics Al Lonstein and Robinson discussed during their interview: Drug use, incarceration, diversity in the workplace, race relations, and the recognition of Negro Leaguers.

When it came to race, the notion of spending time in someone else’s shoes and trying to understand one’s situation came to Al Lonstein when he was hospitalized in the late 1960s with Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Paralyzed from the shoulders down and in an iron lung, he spent much of his time reflecting on himself and other topics.

“He got a lot of introspective soul searching done, and I guess a lot of it led to the Dodgers, to their racial composition,” Wayne Lonstein said. “I guess losing some of your freedom makes you more – I want to say sympathetic or empathetic. You walk in somebody else’s shoes. It may not be the direct, same walk, but you understand when the door closes for no reason other than what you look like or what you are or what you believe in, that’s wrong.”

Drug use and trying to educate youth about drugs and their effects was a topic close to Robinson, whose son, Jack Jr., struggled with addiction. He maintained that education and love were vital in helping youth prevent or escape the lure of drugs.

“I think the parents have to be knowledgeable enough that they can sit down and discuss (drugs) with them and show they have a tremendous concern,” Robinson said. “(Not) sit idly by and let them get into a problem that can take their very life from them. Drugs can and will do that very thing: take their life.

“Jail is not the answer. Love and understanding and a willingness to extend yourself a little bit. Make sacrifices to show that kid you care. If you let that kid go to jail without trying to help him, you’re going to lose him. … I don’t think you just let a kid go to jail without trying to battle, work with him, to give him as much love as you possibly can.”

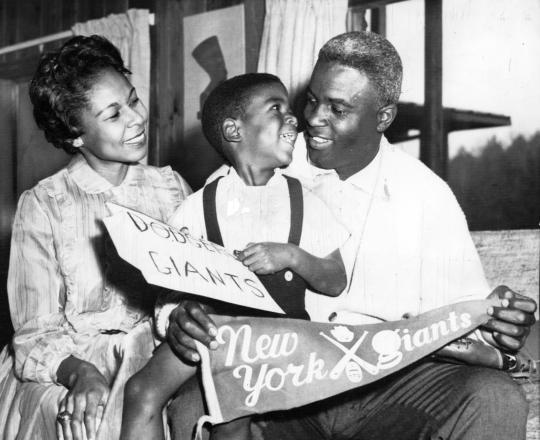

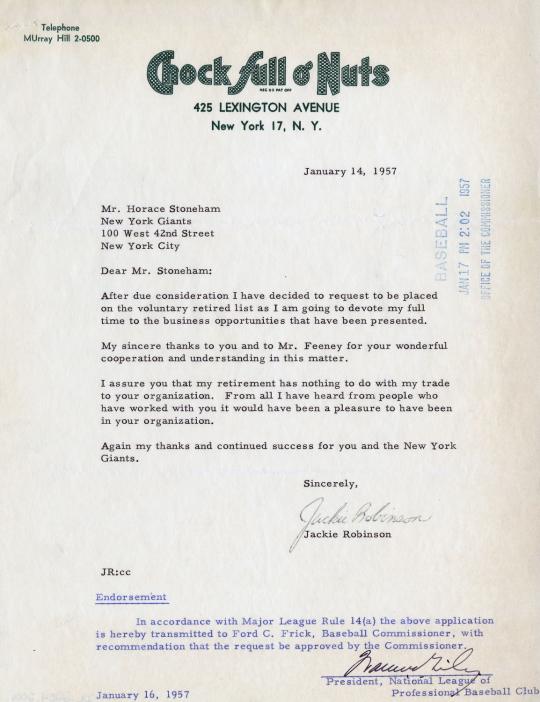

Even more telling is when Al Lonstein asks Robinson about the deal that sent Robinson to the Giants in December 1956 – although he refused to report to his new team, opting for retirement.

“I had already made up my mind that I had quit baseball. I had signed a contract to go to work for Chock Full O’Nuts … 20 minutes before I heard from Mr. Bavasi that I had been sold,” Robinson recalled. “I wanted to leave baseball as a member of the Dodgers. I didn’t, but I don’t have the love for baseball that I once had.”

The notion that this baseball great had felt a diminished love for baseball was something Wayne Lonstein thought added to the significance of this interview.

“I guess that’s why this is an important piece, as well. … Was that regret or the love lost because of the steep price that he paid, not only personally, but to the innocents, which would be his family? There is a price to be paid for greatness, for change and for risk,” he said, at the same time wondering what would be Robinson’s reactions were he just breaking the barrier in today’s society of constant contact and communication.

“I couldn’t imagine what this man went through, what he felt, and what he did. And how it wouldn’t destroy you. Put yourself in his shoes: How would you survive? There’s no way to represent it. And that’s why I thought the import of circling back – this is baseball, this is human condition – this is a lot more than just five minutes on a cassette tape.”

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Preserving Jackie's Legacy

Fourteen-thousand hours.

That’s the estimate of how much original recorded media resides in the Library Archive at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. But while the shelves in the Archive represent the largest collection of recorded baseball history anywhere in the world, many of the stories and information held within have remained largely undiscovered.

The Museum’s audio collection – featuring interviews, oral histories, game broadcasts and more – consists of many different types of media including reel-to-reel tapes, cassettes and microcassettes, 45 rpm vinyl records and even aluminum records. These pieces are preserved in climate-controlled conditions in Cooperstown, but if no one is able to hear what’s on them, their full historical value remains untapped.

As technology evolves, these forms of media run the risk of being left behind. Each passing year makes it more essential to preserve these recordings to ensure they can be enjoyed by future generations.

The Hall of Fame has launched its Digital Archive Project. Through this project, we will digitize the Museum collections and Library archive and offer you on-line access to more than 200 years of baseball history. This interview with Jackie Robinson currently lives on an at-risk magnetic tape format. Your support will help us digitize interviews like this one so we can continue to preserve and make available these legendary voices for future generation.