- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1991 Topps Glenallen Hill

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Glenallen Hill

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

This may be a little hard to digest for some collectors, but it has been 65 years since the Topps Company, formerly known as Topps Chewing Gum, started manufacturing and selling baseball cards. It all began for Topps in 1951, with the issuance of the disappointing Red Back and Blue Back cards, whose financial failures so motivated Topps executive Sy Berger that he came up with what we now regard as the modern day baseball card in 1952. Topps has been off and running ever since, producing cards without fail, through all of the ups and downs of the volatile baseball card industry.

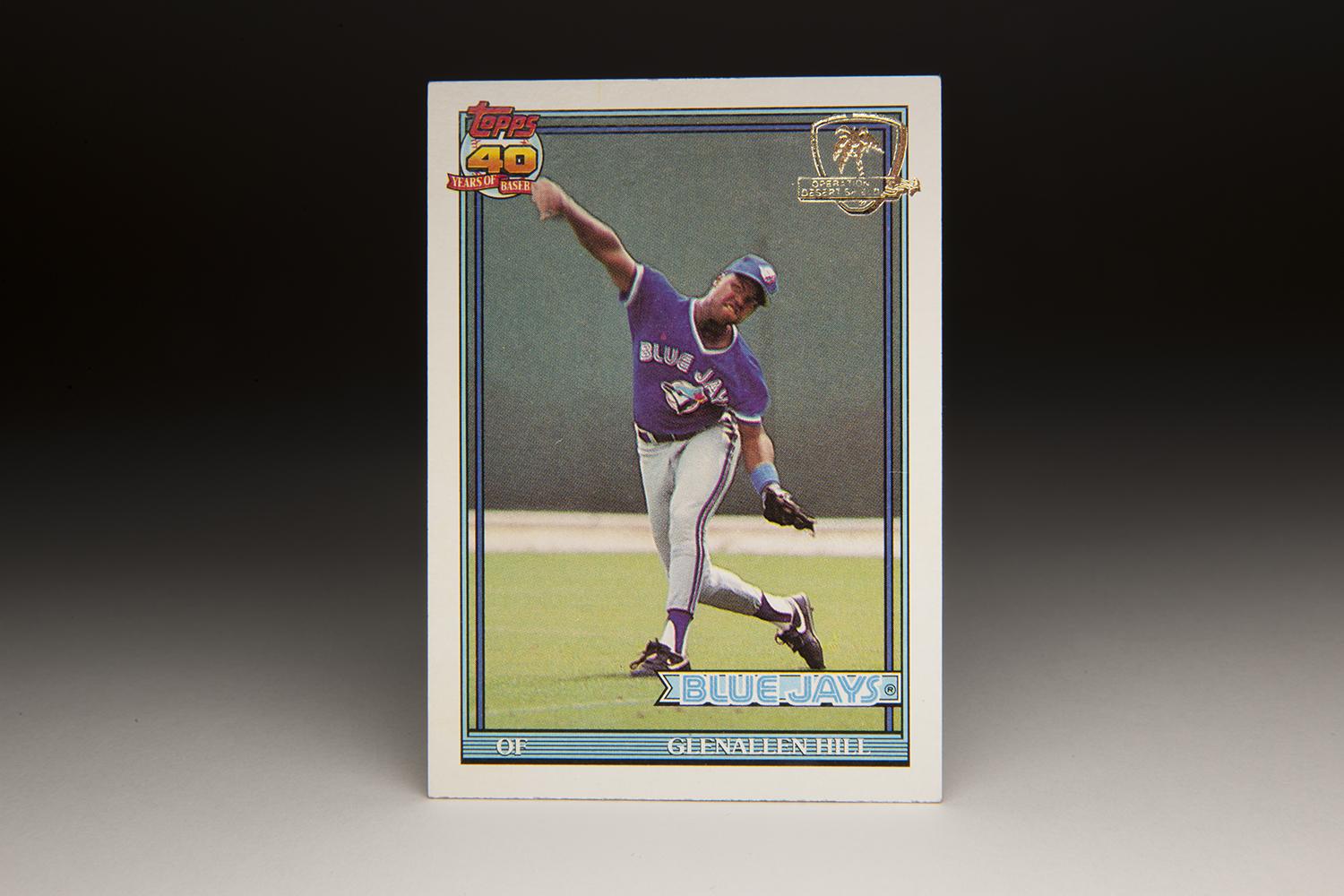

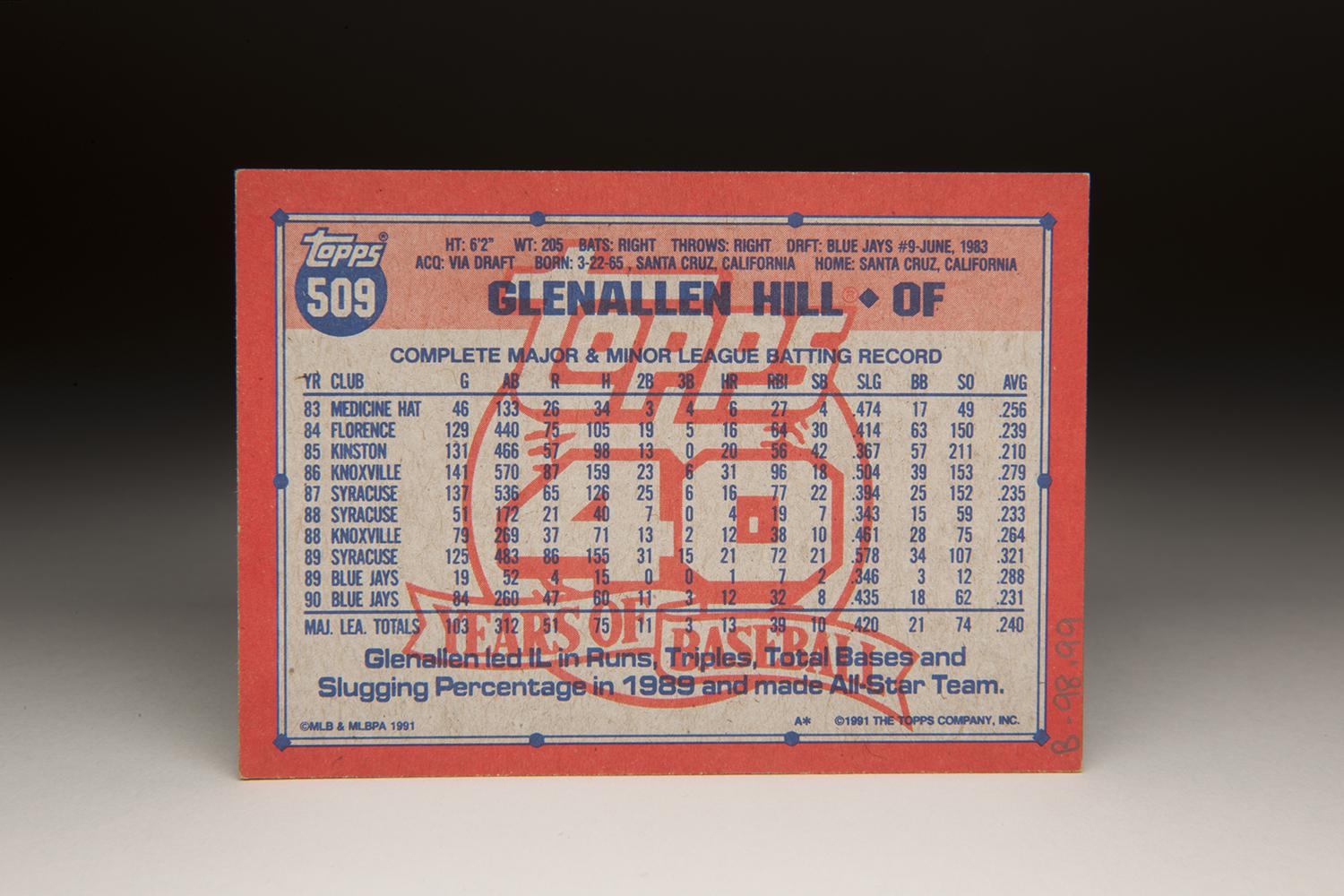

Topps has not often marked anniversaries on the fronts of its card, but it did just that in 1991. On the upper left hand corner of each card, we see a good-sized red and yellow logo marking the 40th anniversary season of Topps cards. That 1991 set remains my favorite from the 1990s - and not just because of the eye-catching logo. With consistently excellent photography throughout the set, the nice colored lines framing each card, and a simple but dignified design, the ’91 Topps cards remain among the best, at least from an aesthetic standpoint.

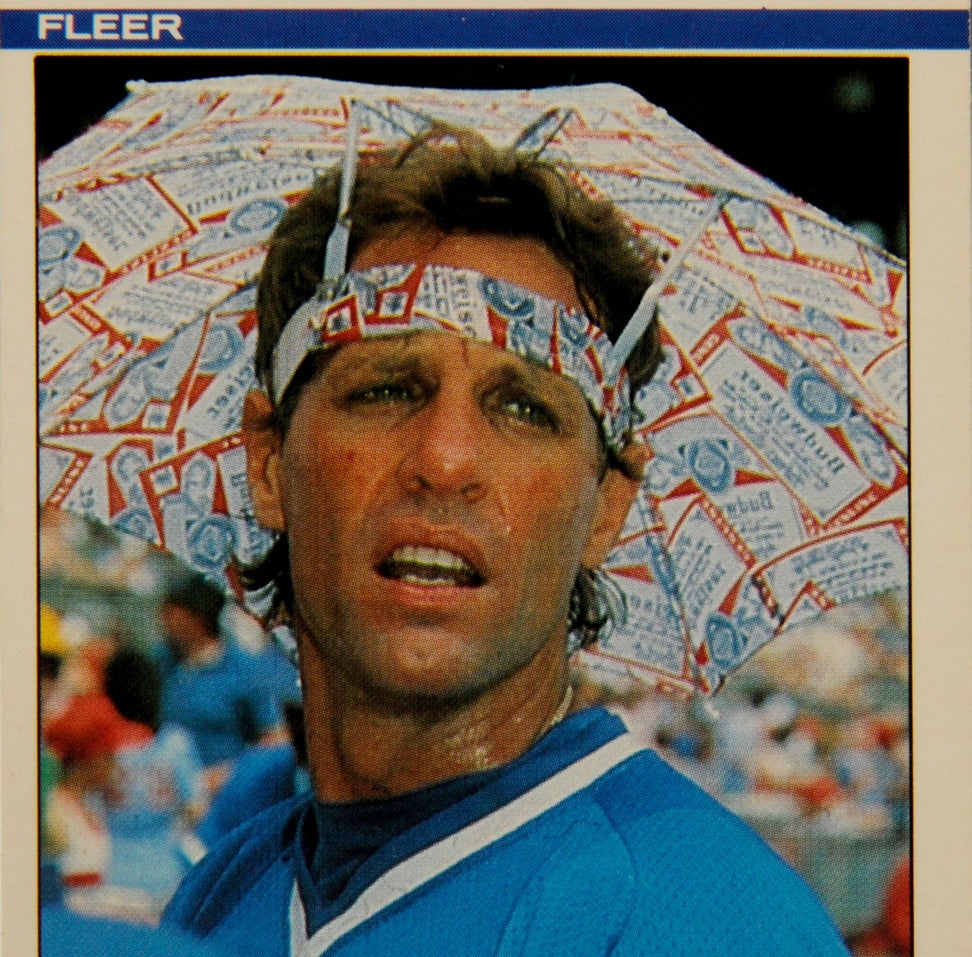

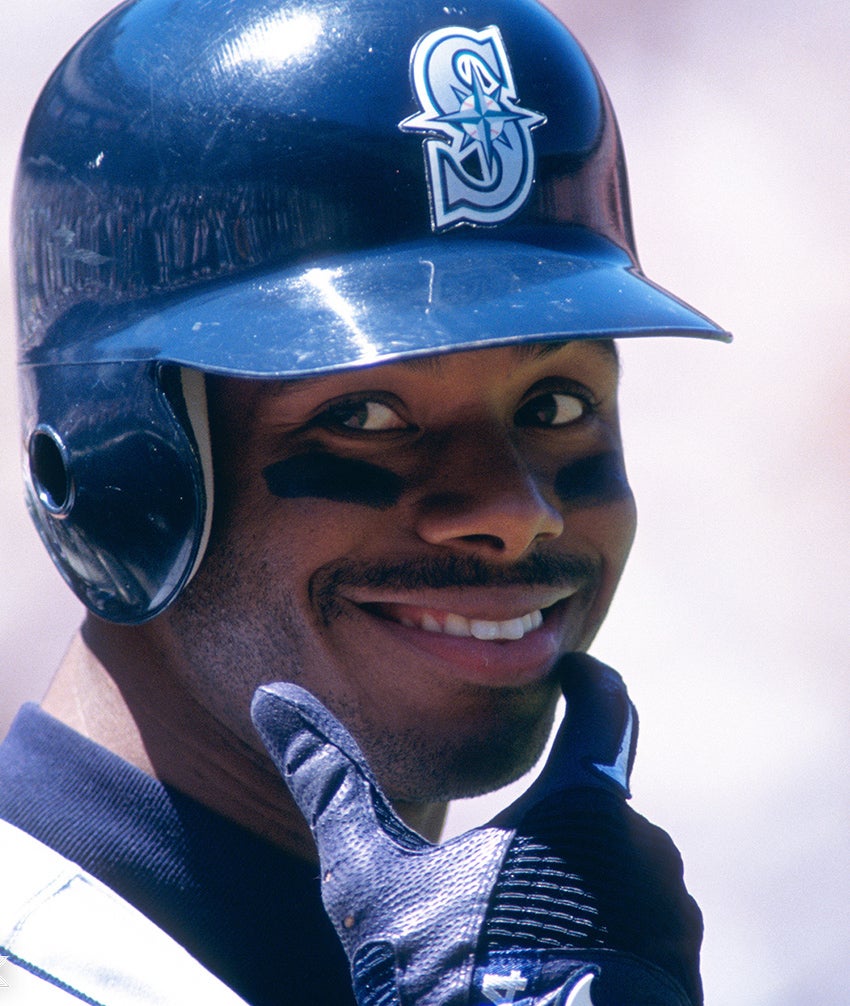

Of all the cards in that set, one of the most unusual is the card of Glenallen Hill, at the time a young outfielder with the Toronto Blue Jays. If you remember Hill, you probably remember him as a hard-hitting designated hitter who had a choppy unorthodox swing that resembled a lumberjack swinging an axe against a tree trunk. When Hill made contact, it was often hard contact in the form of a screaming line drive or a soaring fly ball. Given these strong memories of him as a hitter, it does seem a little bit odd that one of his first Topps cards shows him in a defensive posture, playing right field in what appears to be a Spring Training game.

The action shot is also somewhat unconventional, in that it doesn’t show Hill fielding or catching a fly ball, but rather throwing a ball. And the motion that we see from Hill is awkward. His footwork appears out of sort, and his left shoulder has flown open during his delivery of the ball, while his right arm is fully extended, his head and body are twisted in the opposite direction. There appears to be a lot of stress and strain (which is underscored by his facial grimace), not exactly the textbook way to deliver the ball toward the infield. Given the awkwardness seen here, it’s no wonder that as Hill’s career progressed, he played less and less in the outfield, and gravitated more toward use as a DH.

This was not Hill’s rookie card with Topps. He had appeared on a card one year earlier, part of the gaudy, shaded-border set of 1990. On that card, Hill appeared in portrait, a full close-up with his cap strangely turned upward to hide the logo, in much the way that players appeared on cards back in the 1960s and 70s. The 1991 card, in contrast to the 1990 rookie card, marked his first appearance on an action card for Topps, and remains, at least in this author’s opinion, the most interesting card that Topps ever put out for Hill.

Hill’s big league career actually started in 1989, when the Blue Jays called him up in midseason. He hit a respectable .288, but didn’t hit with much power and didn’t exhibit much patience in 55 plate appearances, drawing only three walks. Still, the Jays saw enough to keep him as a utility outfielder in 1990, filling in as a backup in left field and right field and as an occasional DH. Hill’s batting average fell off into the .230s, but he did show some power, hitting 12 home runs in 84 games.

It was during the 1990 season that Hill earned his nickname, “Spiderman.” While sleeping one Friday night, Hill had a nightmare about spiders. Already afflicted with arachnophobia, he dreamed that a number of spiders were chasing him, which caused him to get out of bed and walk in his sleep. According to Hill, he walked into a wall, bounced off of it, and then climbed a set of stairs. Hill explained what happened next during a discussion with a New York Times reporter. “When I woke up, I was on a couch and my wife, Mika, was screaming, ‘Honey, wake up!’ ” Hill told the Times.

Hill soon discovered cuts on his knees, elbows, hands, and feet, the apparent result of knocking over a glass table during his sleepwalk. After upending the table and breaking the glass, Hill stepped onto the broken shards, exacerbating his condition. He also suffered rug burns from falling onto his knees. The array of injuries necessitated a trip to the emergency room, where he was fitted with crutches.

The “Spiderman” incident received a good share of media coverage in the summer of 1990. By the spring of 1991, Hill was becoming something of an afterthought while the team found itself in need of starting pitching. The Jays had plenty of frontline outfield talent, with Candy Maldonado, Devon White and Joe Carter in starting roles, making Hill expendable. Still regarded as one of Toronto’s top hitting prospects, Hill became part of a trade package, sent with fellow outfielder Mark Whiten and pitcher Denis Boucher to Cleveland for knuckleballer Tom Candiotti.

Headed toward a last-place finish in the American League East, the Indians platooned Hill in center field with another young talent, Alex Cole. But Hill was a bad match for center field, where he lacked the requisite flychasing skills. The following year, the Indians tried him in left, where he was far more comfortable, and watched him hit 18 home runs in a platoon role.

The Indians hoped that Hill would become a key part of their rebuilding, but his inconsistent hitting frustrated them. The front office also questioned him for having “too much attitude” and exerting a bad influence on the team’s other young players. After a slow start to the 1993 season, the Indians lost patience. In late August, they sent Hill to the Chicago Cubs for Candy Maldonado, an older player and Hill’s former teammate in Toronto.

Hill found Chicago and Wrigley Field much to his liking. In 31 games with the Cubs, Hill hit 10 home runs, batted .345, and posted an OPS of 1.157. For many teams, those numbers would have guaranteed an everyday position in 1994.

As well as Hill hit during the stretch run, the Cubs still viewed him as a platoon player. During the strike-shortened season of 1994, he platooned with Tuffy Rhodes in center field and produced solid offensive numbers, including 10 home runs, 19 stolen bases, and an OPS of .826.

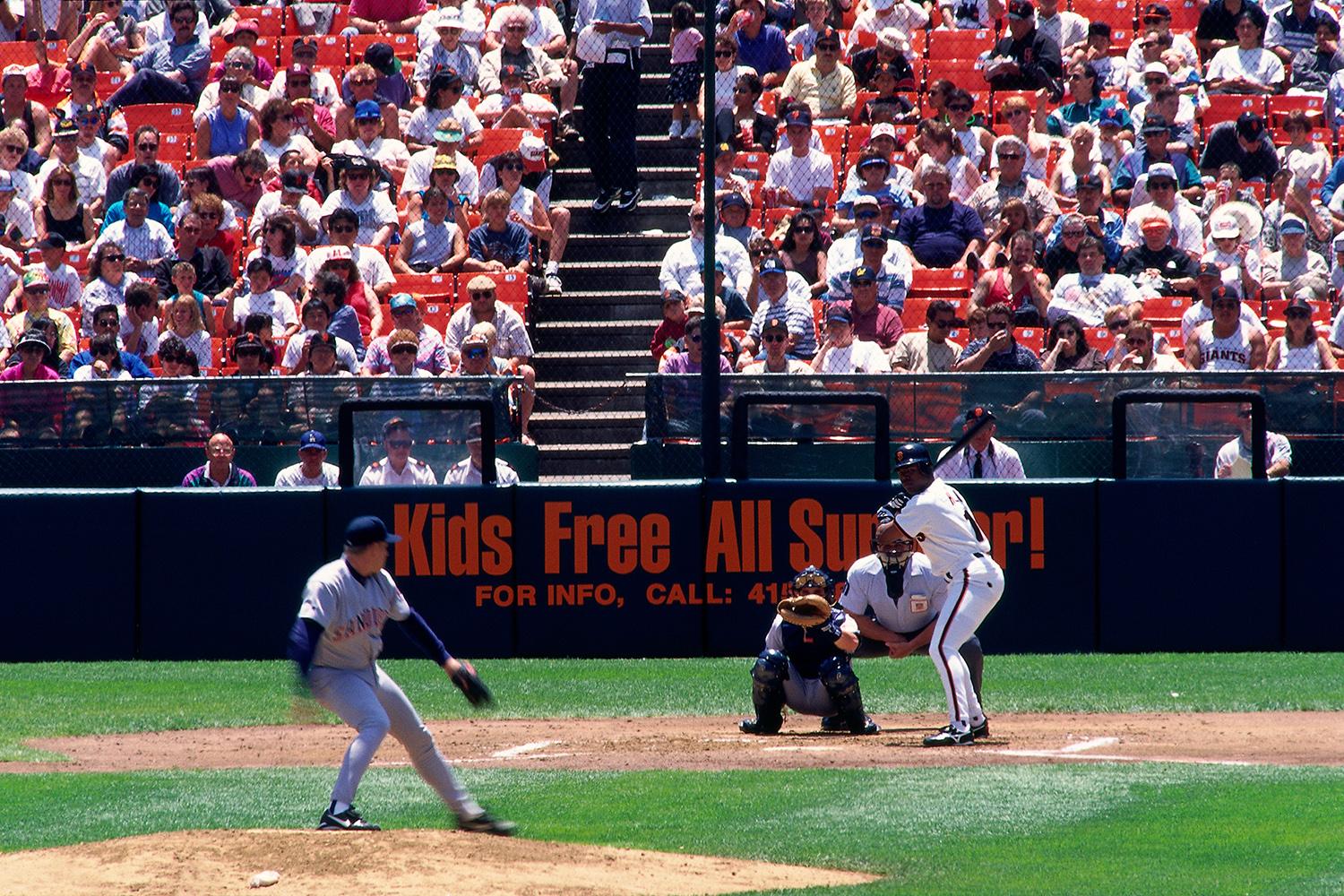

When the player strike ended in the spring of 1995, the Cubs strangely failed to tender Hill a contract, allowing him to become a free agent. Hill departed the Cubs for the promise of more playing time with the San Francisco Giants, who guaranteed him a spot in their starting outfield. It was also a homecoming for Hill, who was born in nearby Santa Cruz. Hill would become popular with the Giants, in part because of his willingness to make public appearances and sign autographs.

For the first time in his career, Hill played regularly. He responded with 24 home runs, 25 stolen bases, and an OPS of .800. He continued to hit well in 1996, but injuries limited him to 98 games. In 1997, he regained his health but his power production fell off badly, as he hit only 11 home runs. That winter, the Giants allowed him to leave as a free agent.

Hill was now 33, but the Seattle Mariners felt he had something to offer and signed him, placing him in the same outfield with Ken Griffey, Jr. and Jay Buhner. Hill hammered the ball for the Mariners, putting up an OPS of .853 in a half-season. In contrast, his defensive play in left field was something less impressive. As former Mariners pitching coach Bryan Price once said, watching Hill play the outfield was “akin to watching a gaffed haddock surface for air.”

Hill’s fielding woes, which resulted in him being called “The Juggler,” frustrated the Mariners. With the M’s headed nowhere in 1998, they decided to explore trade possibilities. Finding nothing of interest in trade talks, they placed Hill on waivers and watched the Cubs put in a claim for their former player. In serious contention in the National League pennant race, the Cubs felt that Hill could help them in August and September.

Hill did just that. In 48 games, he batted .351 and helped the Cubs solidify the wild card berth in the National League. He also picked up his first hit in postseason play, though the Cubs lost to the Atlanta Braves in the Division Series.

Over the next season, Hill continued to rake for the Cubs. He hit for both power and average in 1999 and remained productive through the first half of 2000. In one game at Wrigley Field, Hill smacked a 500-foot home run that completely left the ballpark, crossed Waveland Avenue, and landed on the rooftop of a building across the street.

Hill became a favorite at Wrigley Field, but in late July the Cubs decided to acquire what they could for him, settling for two prospects from the New York Yankees.

Initially, the Yankees planned to use Hill as a bench player. With 11 lifetime pinch-hit homers, Hill ranked as one of the best pinch-hitters in the game. As it turned out, the Yankees needed Hill to do more than come off the bench. With their offense slumping and the team facing a difficult stretch run, Hill carried the Yankee lineup on days that he played, tormenting American League pitching to no end. In 40 games, mostly as the DH, he hit 16 home runs, batted .333, and forged an OPS of 1.112. Hill did it all with his unusually compact swing, which manager Joe Torre compared to “Muhammad Ali’s left jab.”

Thanks to Hill, along with some help of another midseason acquisition (David Justice), the Yankees held on to the American League East title on their way to winning a third consecutive World Series.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

But with the Yankees having an overload of designated hitters and outfielders the following spring, they sent Hill to the Anaheim Angels for a minor league pitcher. He batted only .136 and struck out 20 times in 66 at-bats, leading to his release on June 1. That brought his well-traveled career to an end.

After his playing days, Hill turned to coaching, as a member of the Colorado Rockies staff. An advocate for the safety of coaches, he was one of the first to wear a batting helmet in the first base coaching box, his awareness stemming from the death of Mike Coolbaugh, a fellow coach in Colorado’s minor league system.

Hill now works as a manager in the Rockies’ system, where he has enjoyed success. But his name has also generated news in an unwanted way. The release of the Mitchell Report, an investigation into steroid use overseen by former US Senator George Mitchell, included Hill’s name. He was found to have connections with Kirk Radomski, known as a dealer of PEDs.

For some within the game, the revelations came as no surprise. Due to his hulking frame and his previous admission of using “brain stack” vitamins, Hill had long been rumored to be involved with PEDs, particularly during the latter years of his playing career. Two months after the release of the Mitchell Report, Hill admitted to using PEDs. “I thought about this for a while,” Hill told the Santa Cruz Sentinel while driving to the Rockies’ Spring Training camp. “I wanted to get it all out in the air before I get to Arizona.”

But Glenallen Hill was also memorable for his play at the plate and in the field – as his 1991 Topps card tells us all these years later.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame