- Home

- Our Stories

- O’Neil’s work as a scout opened doors for many players

O’Neil’s work as a scout opened doors for many players

Although Buck O’Neil had already been involved in professional baseball for decades, he did not truly enter the public consciousness until 1994, when director Ken Burns unveiled his expansive documentary, known by the simple title of Baseball. For that film, Burns relied heavily on a number of commentators, ranging from academics to former players.

But no one stood out more than O’Neil, who captivated the country with his vibrant storytelling, his unending energy, his humor and his love of Negro Leagues baseball.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

STORIES OF BLACK BASEBALL

Stories that highlight the lives and experiences of Black ballplayers through key moments in history, artifacts and baseball cards.

O’Neil’s commentary on Baseball made him a national celebrity and baseball’s leading unofficial ambassador, but in reality, he had already forged a remarkable, if overlooked, career in the game. In the 1940s, O’Neil stood as a slick-fielding, contact-hitting first baseman for the Kansas City Monarchs. In 1942, he helped the Monarchs win the Negro World Series. After missing two seasons while serving in the Navy during World War II, he returned to the Monarchs in 1946. Two years later, O’Neil became the Monarchs’ manager, winning three league titles over a span of eight seasons.

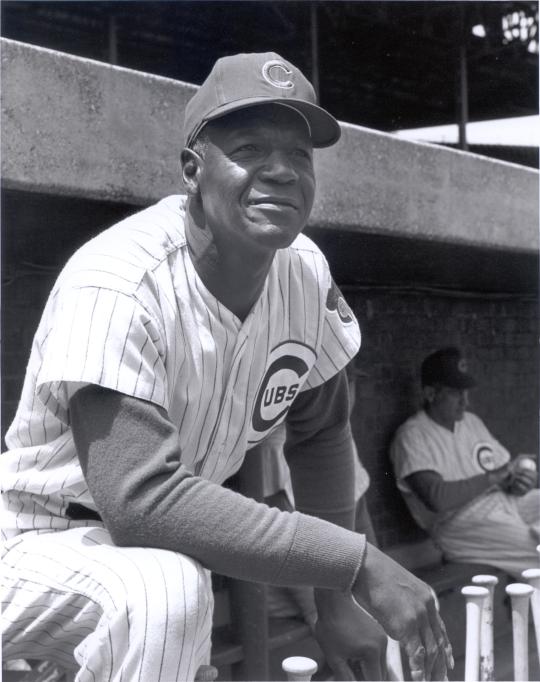

While all of these accomplishments are relatively well-known, O’Neil’s work with the Chicago Cubs remains the least appreciated part of his long baseball tenure. O’Neil served the Cubs as both a scout and coach, the latter position making him part of the team’s famed “College of Coaches” in the early 1960s.

In 1955, O’Neil long tenure as a manager with the Monarchs came to an end. When Monarchs owner Tom Baird sold the team, O’Neil opted to resign. Negro Leagues baseball was already dying, the result of the continuing trend of the top Black players moving on to either the American or National leagues. By that point, O’Neil was past his prime as a player, but his intelligence and enthusiasm made him a natural fit for some major league team’s front office or scouting department.

After that ’55 season in Kansas City, the Cubs offered O’Neil a job as a scout. O’Neil recommended that the Cubs sign three players from the Monarchs’ roster: outfielders George Altman and Lou Johnson, and shortstop J.C. Hartman. Altman would become a productive power hitter with the Cubs in the early 1960s, while Johnson would eventually become a key contributor to the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1965 to 1967

The Cubs assigned O’Neil to travel throughout the South and focus on scouting and signing Black players, whom the Cubs believed might feel more at ease talking to a scout from an African-American background. So O’Neil hopped into his car, an old Plymouth Fury, and traveled throughout the Southern part of the country looking for players who might have a future in the professional game. As a scout, O’Neil possessed a keen eye for talent, along with a personable approach that allowed him to learn about a player’s character, determination and work habits.

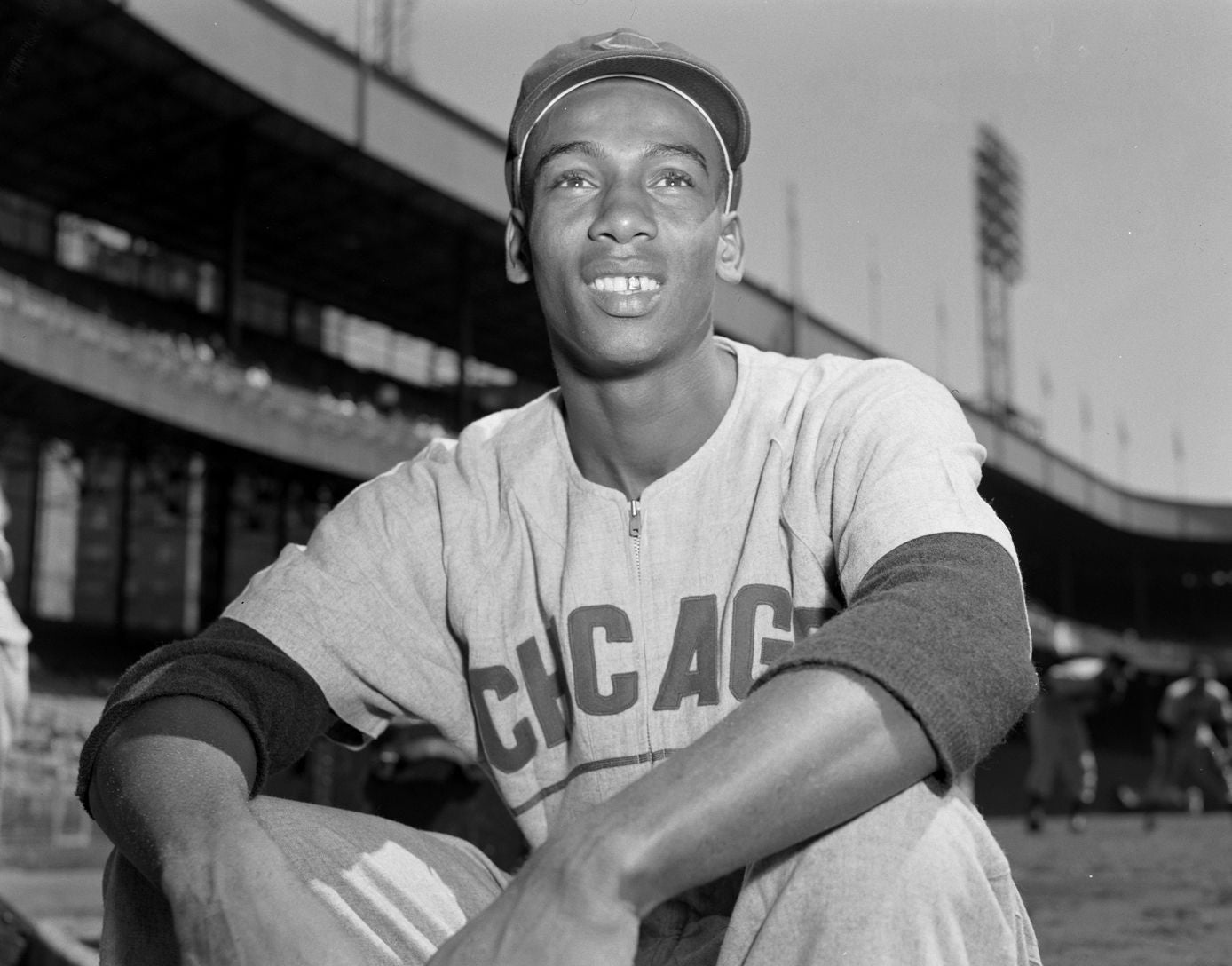

Like most scouts of the day, O’Neil relied little on statistics but far more on what he observed. He looked for bat speed, foot speed and athleticism, among other qualities. And he also looked for character. One of the young players who caught his eye was Lou Brock, an outfielder at Southern University. On O’Neil’s recommendation, the Cubs invited him to a tryout camp. After the camp, O’Neil offered him a contract, as did the crosstown Chicago White Sox.

Ultimately, Brock chose the Cubs because he felt that they offered him a better and clearer path to the major leagues. But O’Neil’s personality and approach also played a part in Brock’s decision. “He got me started on a journey that became a 19-year major league baseball career,” Brock would tell the Associated Press many years later in describing O’Neil’s impact on his life “He shaped the character of young Black men. He touched the heart of everyone who loved the game. He gave us all a voice that could be heard on and off the field.”

Brock would make his debut with the Cubs in 1961, when he received a four-game cup of coffee. The following season, Brock found a more permanent place on the Cubs’ roster. In May of 1962, O’Neil changed jobs with the Cubs, moving from a scouting role to a position on the team’s coaching staff. In so doing, O’Neil became the first Black coach in the history of either the National League or the American League.

The position allowed O’Neil to work more closely with Ernie Banks, one of the players he managed with the Monarchs back in the early 1950s, and a young Billy Williams. As a coach, O’Neil believed in the importance of instruction and positive reinforcement. “When a fellow makes a mistake, you don’t ride him,” O’Neil said in an interview with Ebony magazine. “You show him what he’s supposed to do and make him believe he can do it. You have to make him believe in himself.”

By the start of O’Neil’s coaching tenure in Chicago, the Cubs had instituted their College of Coaches. It was a radical system in which there was no full-time manager, but the organization allowed each uniformed coach to take turns leading the team. The Cubs had begun this unconventional approach in 1961 and continued it in 1962. During the latter season, coaches Elvin Tappe, Lou Klein and Charlie Metro took their turns as managers. But for O’Neil, that chance never came. Despite promises from the Cubs’ front office that he would have his turn to manage, the Cubs bypassed Buck completely in 1962. While the Cubs never offered a public explanation, it’s highly likely that race played a factor in the decision.

In 1963, the Cubs retained the name of a College of Coaches, but took on a more traditional approach, as they gave the position of “head coach” to one man, Bob Kennedy. O’Neil would never manage in Chicago but remained part of the Cubs’ coaching staff through the 1965 season, before moving back to his prior role as a scout.

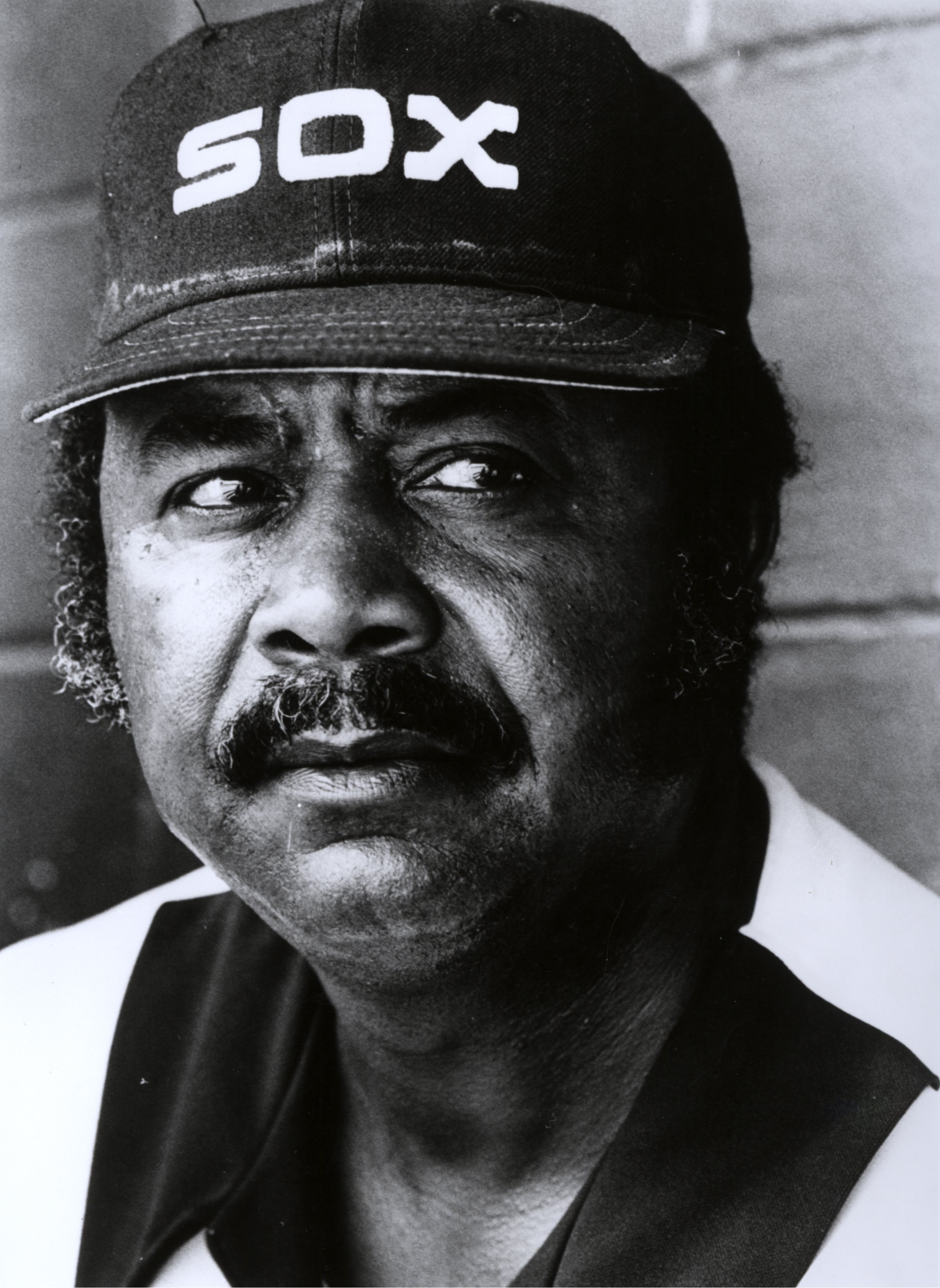

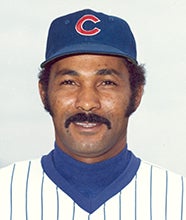

Scouting allowed O’Neil to have a larger impact on the organization. In 1968, O’Neil went on what would become a famous scouting expedition in Montgomery, Ala.. There he watched a group of amateur players, most of whom were clearly not prospects to play professional ball. But there was one player who did stand out, an 18-year-old named Oscar Gamble. O’Neil talked to Gamble briefly and set up an appointment to watch him play the next day. Coming away impressed with Gamble’s bat speed and power, O’Neil signed him for the Cubs. Although Gamble would play only briefly for the Cubs in 1969, he would eventually become a productive outfielder with the Cleveland Indians, Chicago White Sox, New York Yankees, and Texas Rangers, hitting 200 home runs over a 17-year career.

During the 1970s and 80s, O’Neil became heavily involved in several other prominent signings. In 1973, he signed right-hander Donnie Moore, a first-round selection in the January draft. Moore would struggle with the Cubs before finding a niche as a closer with the California Angels.

In 1975, O’Neil signed a tall right-hander named Lee Smith, taken in the second round of the draft that spring. By 1980, Smith made the Cubs’ roster and would post 180 saves over eight seasons in Chicago, marking the start of a Hall of Fame career.

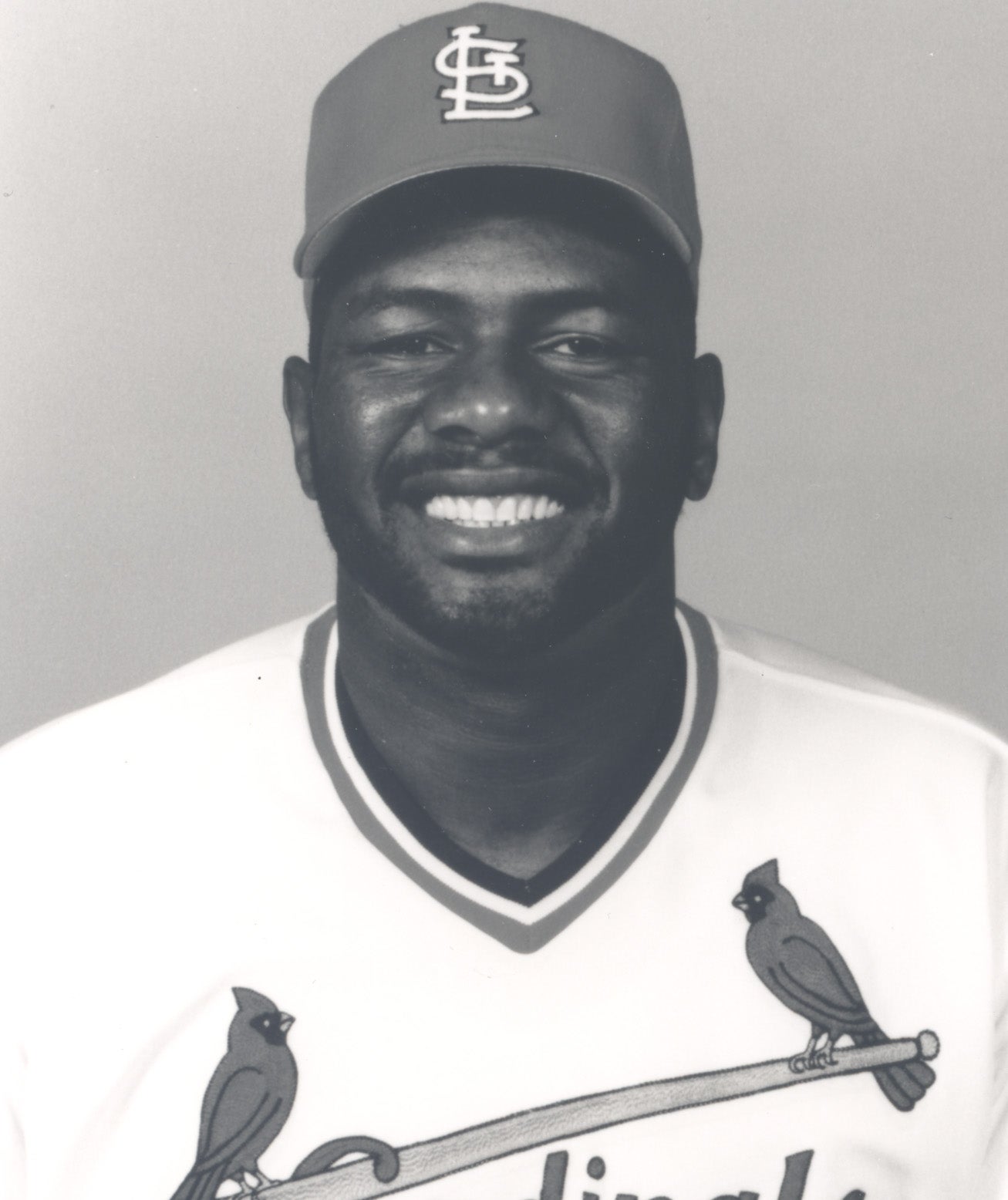

In 1981, O’Neil signed outfielder Joe Carter, whom the Cubs had taken with their first-round draft choice only a few days earlier. Carter would play only briefly for the Cubs but would become an important player in a historic trade. Two days before the June 15th trading deadline in 1984, the Cubs sent Carter to the Indians as part of a package for Rick Sutcliffe, who would post a record of 16-1 and help Chicago win the National League East that summer. In the meantime, Carter emerged as a force with the Indians, on his way to 396 career home runs.

O’Neil remained with the Cubs through 1988, when he left the organization to make a return to Kansas City, this time with the Royals. There he also served as a scout, working the Midwest region, which allowed him to stay closer to home.

O’Neil was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2022, 14 years after he was named the first winner of the Museum’s Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award. There is little doubt that O’Neil’s work as a scout and coach helped the Cubs, both in terms of his uplifting influence on established players like Banks and Williams and in his ability to sign young, unproven talents, including two who would precede him into the Hall of Fame.

While we tend to think of Buck O’Neil as a Kansas City Monarch first and foremost, the Chicago Cubs are surely happy to call him one of their own, too.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum