- Home

- Our Stories

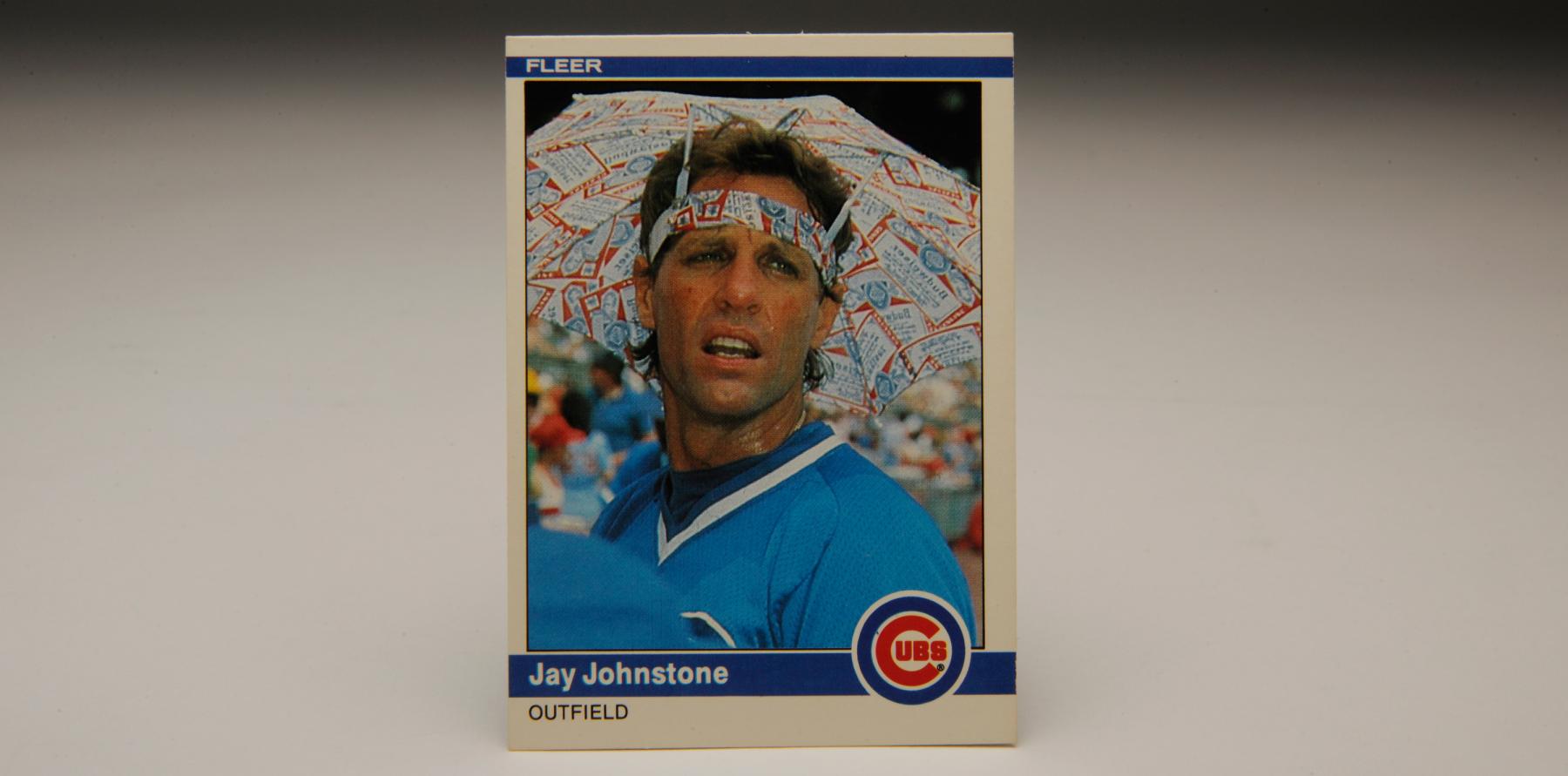

- #CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Jay Johnstone

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Jay Johnstone

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Jay Johnstone seems oblivious to the fact that he is wearing an umbrella on his head. He seems far more interested in something off in the distance. Perhaps someone is calling to him. Or maybe something has caught his eye. Whatever the case, he looks as natural as anyone can while wearing an umbrella as a hat and simultaneously sporting his blue-topped Chicago Cubs uniform.

What Johnstone is actually wearing on this 1984 Fleer card is a “Brockabrella.” It was a hat designed in the 1970s, with Hall of Famer Lou Brock as spokesman. The idea was simple. The Brockabrella was designed to keep one’s head dry from the pounding rain while also keeping one’s hands free. It was a stroke of brilliance and pure genius.

The Brockabrella also became an unusual fashion piece. It’s just the kind of thing that Johnstone would have worn. But how exactly did he come to wear the Brockabrella on the day that his baseball card picture was snapped? “It was a muggy ‘Photo Day’ at Wrigley Field,” Johnson recalled in an interview with Sports Collectors Digest. “I was walking around the outfield when I decided to go back to the dugout and get the Brockabrella.” Johnstone figured the device would give him some protection from the hot sun.

Johnson wasn’t aware that the Fleer photographer was even taking his picture. “I didn’t pose for it,” said Johnstone. “You can see how red my face was, it was so hot and muggy.” An unsuspecting photo target, Johnstone had made baseball card history. Years later, Johnstone revealed that Budweiser, the company featured on the Brockabrella, rewarded him with a case of complimentary beer each summer.

When it came to such colorful, offbeat behavior, and a sideways sense of humor, few could close to matching John William Johnstone, Jr.

Even in high school, Johnstone did things in an unconventional way. A terrific athlete at Edgewood High in West Covina, Calif., he signed nine letters of intent to play football for nine different colleges. Not only did that set some sort of unofficial record, it was slightly against NCAA rules. Thankfully, the California Angels bailed Johnstone out of any potential trouble by signing him to a professional baseball contract on the very day that he graduated from Edgewood High.

When Johnstone joined the Angels as a rookie in 1966, his venerable manager, Bill Rigney, gave him an intriguing place in the clubhouse. Rigney placed Johnstone at a locker located in between those of Bo Belinsky and Dean Chance, two of the game’s most colorful characters. Rigney then gave Johnstone his roommate assignment: the incomparable Jimmy Piersall.

Johnstone had been a quiet, unassuming high school student. That all changed with the Angels. With Piersall becoming his guru, and Belinsky and Chance providing their own unique influence, Johnstone quickly developed into a clubhouse clown, one who could pull a prank at any time or give a writer an unusual quotation or two.

Within a short span of time, Johnstone became known as “Moon Man” to his teammates. Angels pitcher Fred Newman came up with the moniker. Newman and Johnstone had once stayed out past curfew during spring training. When they arrived at their hotel, they both realized they had left their keys in the room. Not wanting to approach the front desk, and perhaps tip off their manager that they had been out late, they decided to run with an alternative plan. As Newman explained, Johnstone pried open a window to their room “by the light of the moon.” Hence the nickname Moon Man.

Fun and likeable, Johnstone fit in well in the California clubhouse, but his frequent defensive mishaps in the outfield frustrated Angels management. So after the 1970 season, the Angels traded Johnstone and two other players to the Chicago White Sox in a deal for Gold Glove outfielder Ken Berry. With Chicago, Johnstone continued to show flashes of brilliance but also provided too many fits of frustration. A .188 batting average in 1972 didn’t help either. The White Sox released Johnstone during spring training in 1973, leaving him temporarily unemployed.

Fortunately, Johnstone had received an earlier promise from another major league owner, indicating that if he were ever to be released, he would have a standing offer of a job. That is how Johnstone came to be matched with an owner fitting of his comedic personality, Oakland A’s patriarch Charlie Finley. Living up to his initial promise, Finley signed Johnstone to a minor league contract.

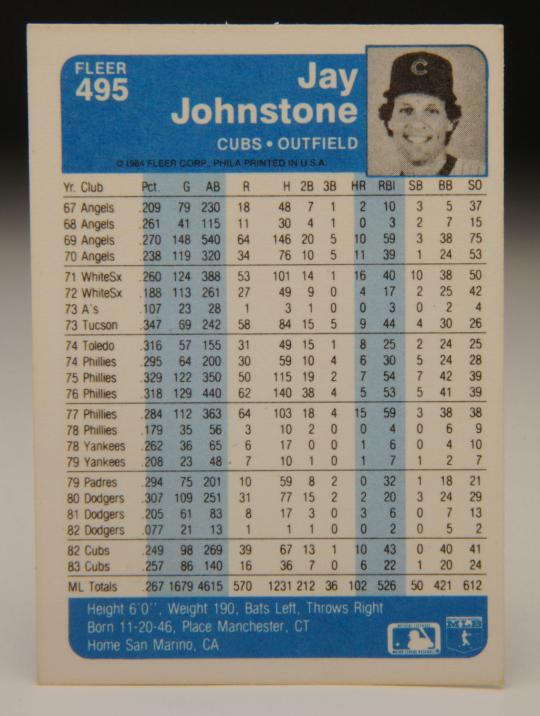

In the midst of the 1973 season, the A’s recalled Johnstone from their Triple-A affiliate at Tucson, where he was attempting to begin his climb back toward the major leagues. The free-spirited Johnstone seemed like a perfect fit for the wild, Swingin’ A’s, a team full of players that reveled in fighting amongst themselves while also defying their owner. But Johnstone struggled to hit for the A’s, and eventually became a victim of Oakland’s crowded outfield. Over the winter, the A’s sold Johnstone’s contract to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Johnstone hit well in the spring of ’74, but the Cardinals had no room for him on their roster, so they released him in late March. Johnstone again found employment, this time with the Philadelphia Phillies’ organization. Assigned to the Triple-A Toledo Med Hens, Johnstone began his second climb toward the major leagues. Once promoted to Philadelphia, Johnstone found himself paired with a lenient manager. Regarded as a players’ manager and one who had a good sense of humor, Danny Ozark seemed to understand and appreciate his journeyman outfielder, even though he would do or say almost anything. “What makes him unusual is that he thinks he’s normal,” Ozark explained to a reporter, “and everyone else is nuts.”

Ozark and the Phillies came to appreciate Johnstone as a valuable part-time player and pinch-hitter. At one point, he shared time in right field with Ollie Brown, forming one of the most effective platoons in the game. At times, Johnstone also tested the Phillies’ patience. He sometimes missed signs from the third base coach, didn’t always run hard on ground balls and pop-ups, and developed a strange habit of throwing the bat at the ball on pitches that fooled him.

As a member of the Phillies, Johnstone solidified his reputation. He diligently shined his shoes before the first pitch of every game, so that he could see his reflection in the shoe tops. He wore unusual headgear before and after games, including an oddly shaped helmet that featured the words “Star Patrol.” He also shot off firecrackers with regularity from his locker. One time Johnstone waited until NBC “Game of the Week” broadcaster Joe Garagiola started a live interview with to ask questions of Philadelphia Phillies first baseman Dick Allen. Once the interview began, Johnstone set off a firecracker, a very loud firecracker, which made its way onto national television.

Another one of Johnstone’s memorable stunts took place during the 1977 winter meetings in Los Angeles. After dining at a restaurant called “The Cove,” Johnstone stood outside while waiting for the valet parking attendant to return his car. As he waited, Johnstone struck up a conversation with several other restaurant patrons. Recognizing him, they asked Johnstone what he did to keep his batting stroke sharp during the winter. Not wanting to miss an opportunity to illustrate his methods, Johnstone opened up the trunk and took out a batting tee, a tennis ball, and a bat. He placed the tennis ball on the tee and then took a firm whack, hitting a line drive down 7th Street in LA.

In 1980, Johnstone joined the Dodgers, helping to form one of the wackiest clubhouses in history. Johnstone joined a cast of comical and offbeat characters, including Ken Brett, Doug Rau, Jerry Reuss, and Don Stanhouse, of “Stan the Man Unusual” fame.

As a backup outfielder with the Dodgers, Johnstone found intriguing ways to fill down time at the ballpark. Johnstone once paid a visit to the concession stand – after the game had begun – and stood in line while wearing his full baseball uniform. When his turn came, Johnstone ordered a hot dog, before casually returning to the dugout.

In a 1981 game, Johnstone and Reuss, both feeling a bit bored, decided to dress up as groundskeepers and join the grounds crew in dragging the infield during the fifth inning. As soon as Johnstone returned to the dugout, Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda called out his name, indicating that he wanted the veteran outfielder to pinch-hit. Still in a state of undress as he walked to the plate, Johnstone proceeded to hit a home run that helped the Dodgers win the game. Nonetheless, Lasorda levied a fine against Johnstone for being out of uniform.

Always friendly and receptive, Johnstone’s sense of humor extended beyond stunts and pranks. He rarely conducted interviews without his tongue planted in his cheek. “I want to play until I’m 40,” Johnstone told sportswriter Gary Stein while playing as a backup outfielder for the Cubs in 1983. “I drink a lot. I smoke a lot. I do all the right things.”

Nearly overcoming the odds, Johnstone played for two more seasons, including a brief return to Los Angeles, before his career came to an end in 1985, just a year short of his 40th birthday. Although Johnstone’s behavior often overshadowed his performance, it’s worth noting that he lasted 16 seasons, hitting a respectable .267 with 102 home runs. Along the way, he earned two World Series rings, one with the New York Yankees and the other with the Dodgers.

After his playing days, Johnstone parlayed his sense of humor and outgoing personality into a career as a broadcaster and author. He worked as a color commentator on radio broadcasts for the Yankees and Phillies and even hosted his own television talk show. He made a cameo appearance in the hysterically memorable 1988 film, The Naked Gun, one of six acting credits to his name. (Normally a left-handed hitter, Johnstone appeared in the film as a right-handed batter for the Seattle Mariners.) Johnstone has also written several books, including Temporary Insanity, Over the Edge, and Some of My Best Friends Are Crazy. All three titles encapsulated his unique sense of humor.

As with the readers of those books, anyone who has collected his 1984 Fleer card knows all about the delightful antics of the Moon Man, Jay Johnstone.

Bruce Markusen is the Manager of Digital and Outreach Learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum