- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Billy Cowan

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Billy Cowan

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

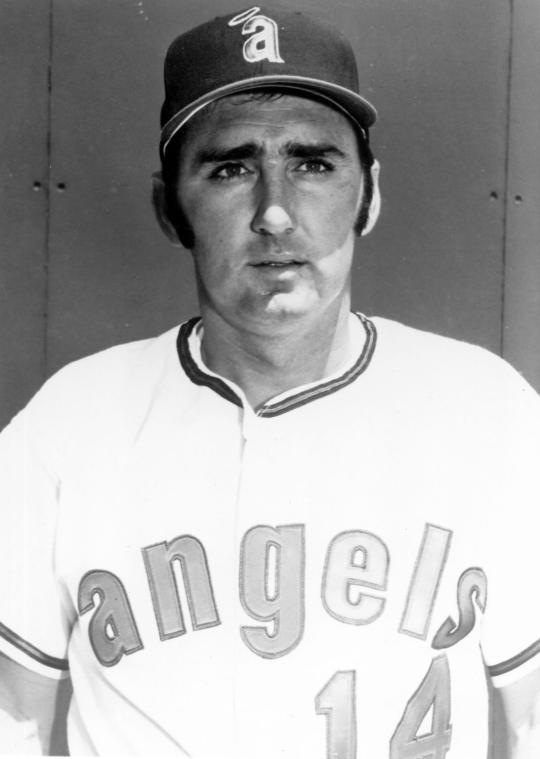

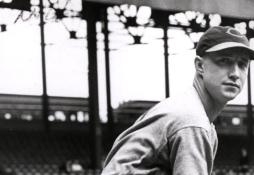

Billy Cowan was the consummate journeyman. That might not sound particularly flattering, but it should not be interpreted as an insult either. For a player to last eight seasons in the major leagues, when the average career is only about four seasons, that is an accomplishment in and of itself.

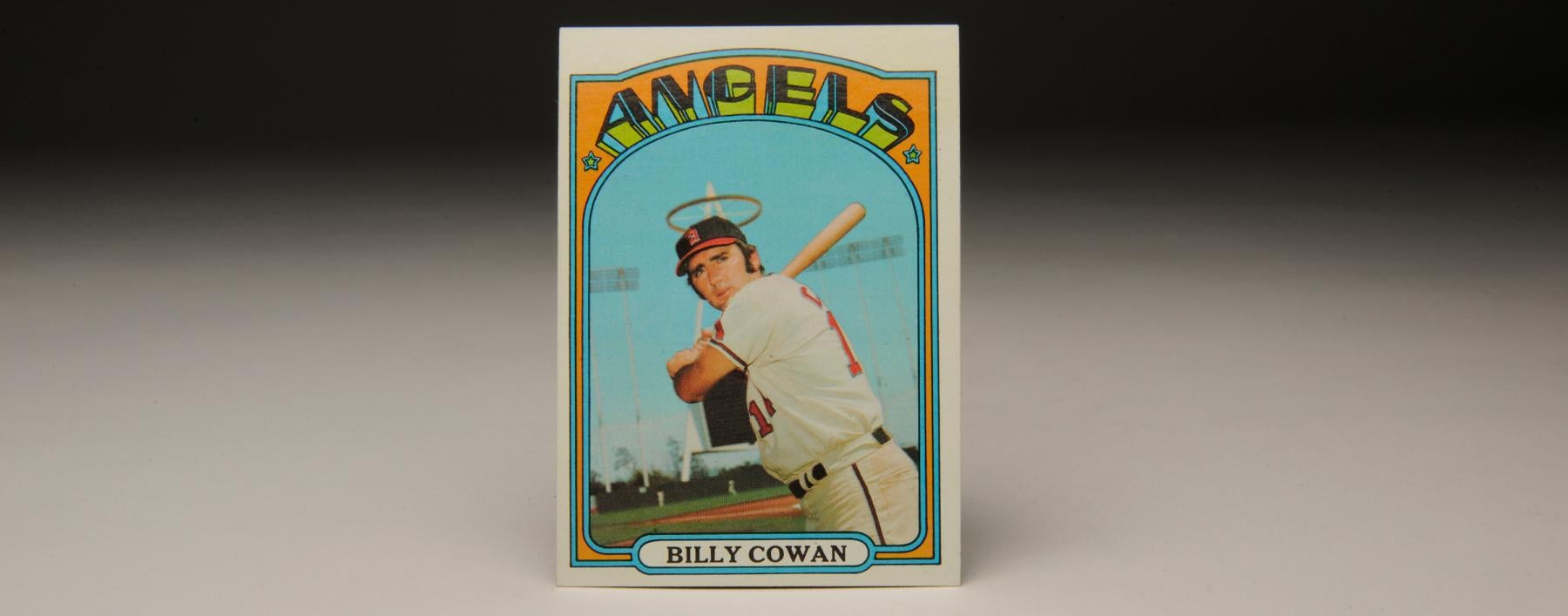

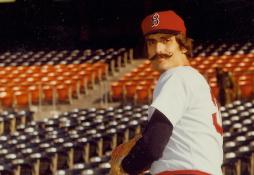

It’s true that Cowan was never the best player on any of his teams and was never an All-Star. Yet, he receives more autograph requests through the mail than most journeyman outfielders of similar vintage – if only because of his amusing 1972 Topps card. Opting to have some fun with Cowan, the Topps photographer lined his head up perfectly within the confines of the old halo at Anaheim Stadium, now known as Angel Stadium of Anaheim. At the time, the ballpark still featured a large halo at the top of a tower within the perimeter of the ballpark. The Halo still stands, but is now featured in one of the stadium’s parking lots.

One thing collectors have always wondered about the Cowan card is whether the outfielder was actually aware of what the photographer was doing. It certainly looks like the photographer intentionally set up the photo so that Cowan’s head was right in the middle of the halo, but it’s not certain that Cowan realized that. Either way, Cowan has maintained his sense of humor about the unusual pose, along with his willingness to sign the card whenever it’s sent to him in the mail.

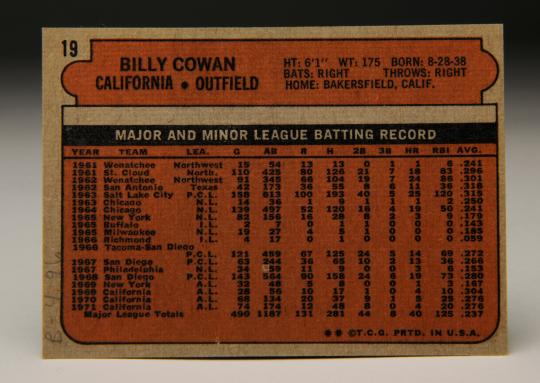

The 1972 card, by the way, was the last one issued for Cowan, who was finishing up his career with his sixth different team. Signed by the Chicago Cubs in 1961, Cowan made an immediate impact as a minor leaguer, hitting 19 home runs as a rookie in pro ball and then winning the Pacific Coast League MVP Award in 1963. That September, he moved up to the Cubs’ roster and made his big league debut. By 1964, he had assumed the starting center field position, taking his place next to Hall of Fame left fielder Billy Williams. Cowan showed promise, hitting 19 home runs and stealing 12 bases while playing a capable center field.

If there was a concern about Cowan, it was his inability to take pitches. He drew only 18 walks for the entire season. So that winter, the Cubs dealt him to the New York Mets for power-hitting George Altman. Cowan struggled in a Mets uniform, batting only .179 while striking out 45 times against only four walks. By mid-season, the Mets had decided to move on; they traded the free-swinging Cowan to the Milwaukee Braves for two players to be named later.

Over the next few seasons, Cowan bounced from Milwaukee to Philadelphia and back to New York, this time with the Yankees, with some minor league service time interspersed onto his resume. He didn’t really find a home until the Yankees sold his contract to the California Angels in the middle of the 1969 season. Settling into a role as a reserve outfielder behind starters like Jay Johnstone and Alex Johnson, Cowan played well over the next two and a half seasons. He hit in the .270 range while filling in at all three outfield positions, along with first base and third base. Cowan emerged as one of the more valuable backup players in the game.

In addition to finding a niche as a ballplayer, something else noteworthy happened during his time with the Angels. Cowan became one of the targets of Morganna Roberts, a dancer and comic performer known as the famed “Kissing Bandit.” (Roberts would later became a part-owner of a minor league team, the Utica Blue Sox, located only 40 miles from Cooperstown.) As was the custom of the day, Cowan received an on-field kiss from Morganna, who had eluded security and made her way onto the playing field. Cowan joined contemporary stars like Clete Boyer, Frank Howard, and Pete Rose, all far better known players who had been “smooched” by the famous Bandit.

Then came the 1972 season, the year of Cowan’s historic baseball card. The Angels, like the 23 other teams in existence at the time, went on strike at the tail-end of spring training, delaying the start of the 1972 regular season. The decision to strike may have influenced the eventual end of Cowan’s major league career.

Cowan was the Angels’ player representative, not a desirable position at the time because of the friction between the players and owners over the negotiation of a new collective bargaining agreement. Even after the strike, which persisted into the middle of April, came to an end, bitter feelings remained between the owners and players.

Cowan played sparingly in the early part of the regular season, coming to bat three times, all as a pinch hitter. And then without warning, the Angels released Cowan on May 2.

Once labeled by the Sporting News as the “Clarence Darrow of the clubhouse,” Cowan believed that he had been given an unfair reputation as a clubhouse lawyer. He decided to file a grievance against the Angels through the Players’ Association, claiming that his release from the Angels had occurred for reasons other than baseball ability.

Having been the Angels’ top pinch-hitter in 1971, Cowan contended that California had cut him loose because of his active role as the Angels’ player representative. Like Cowan, three other player representatives for the Angels had also been dispatched in recent years: Infielders Jim Fregosi and Bobby Knoop had been sent packing in trades and catcher Bob “Buck” Rodgers had been demoted to the minor leagues.

After the Angels released Cowan, no other team came calling. At 33 years of age, Cowan retired.

To Cowan’s credit, he found success after baseball, becoming a real estate investment consultant. He gained a lucrative income from that position, along with the flexibility to play golf on Wednesday and Friday afternoons and to go on fishing trips during the weekend.

All these years, Billy Cowan is still remembered, not for real estate and not even for being a journeyman outfielder who bounced from team to team to team. His signature remains his 1972 baseball card, with his head framed by the Angels’ halo thanks to a creative Topps photographer.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame