- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Ramon Hernandez

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Ramon Hernandez

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

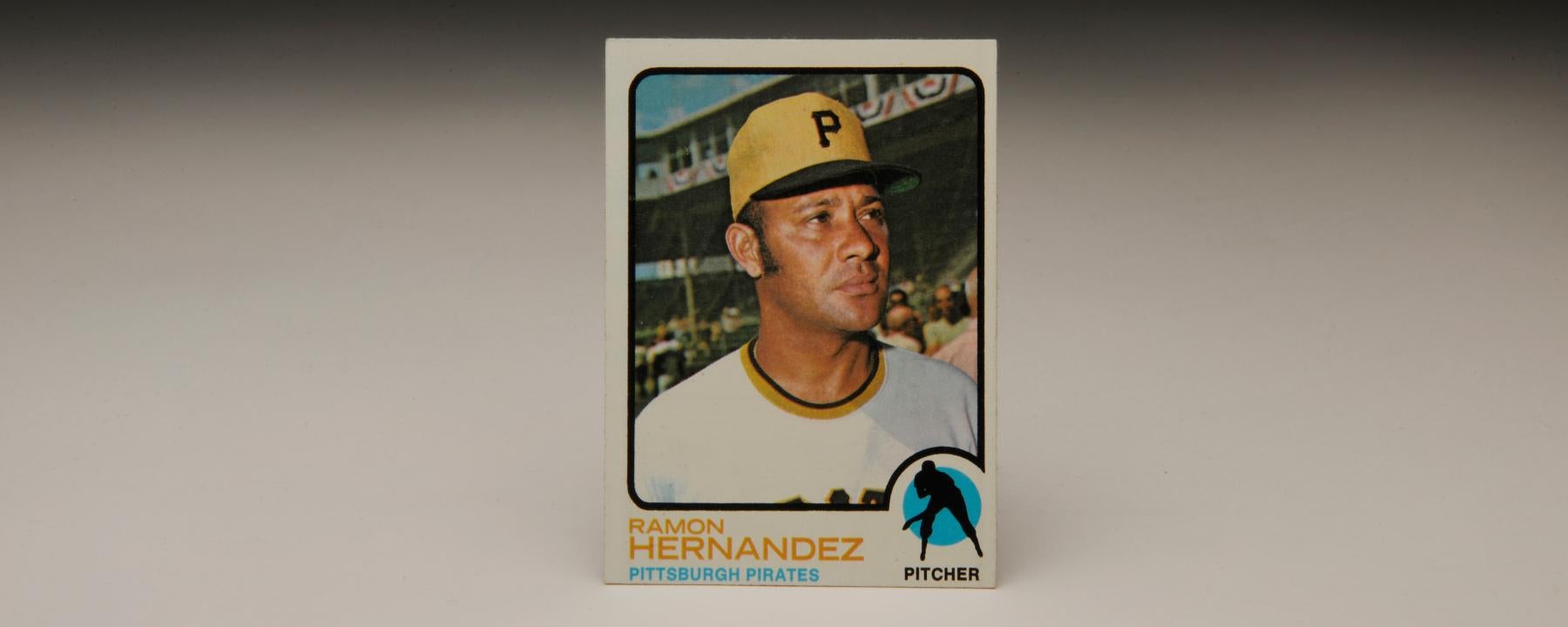

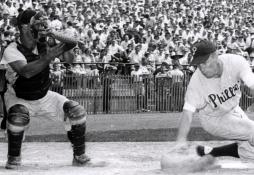

At first glance, the presence of red, white, and blue bunting on Ramon Hernandez’ 1973 Topps card indicates that this photograph was taken during the World Series, possibly the 1971 Fall Classic when the Pittsburgh Pirates played the Baltimore Orioles. But a closer examination negates that possibility. The stadium’s upper deck does not resemble either Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, or Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, the two venues of the ‘71 World Series.

So maybe it was from Opening Day in 1972. A check of the schedule that year shows the Pirates playing at Shea Stadium in New York City. That background does not look like the old ballyard in Queens, either.

That leaves open the possibility that the picture was taken at McKechnie Field in Bradenton, Florida, where the Pirates have held spring training since the 1960s. I’m not sure why a spring training site like McKechnie Field would have featured the colorful bunting, but I suppose it’s possible that’s how the park was decorated in the spring of 1972, as an acknowledgment of the Pirates winning the World Series the previous fall.

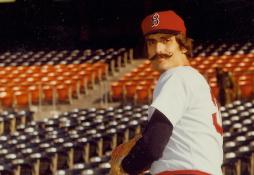

Whatever the occasion, spring training or not, this game was obviously serious business for Ramon Hernandez. Although his picture is being taken by a Topps photographer, Hernandez has chosen not to look at him, but rather to the left of the camera. Unsmiling, he looks stern and staid, perhaps even somber. For Hernandez, this is business as usual, serious business, and not an occasion for joking or merriment. That’s just the way Hernandez was.

Hernandez died in 2009 at the age of 68, his cause of death never publicly announced. Though his career was relatively obscure, he was important because of the small but vital role he played in helping the Pirates win the 1971 World Series. That team became the subject of a book that I wrote, The Team That Changed Baseball.

Hernandez was also a very good pitcher for most of his big league career, far better than most historians remember. How good was he? In 1972, he was just about the best relief pitcher in the National League, that’s how good. In 1973 and ’74, he was arguably the best left-handed reliever in the league. Beyond that, he was an unusual character. For all of those reasons, Ramon Hernandez deserves to be remembered.

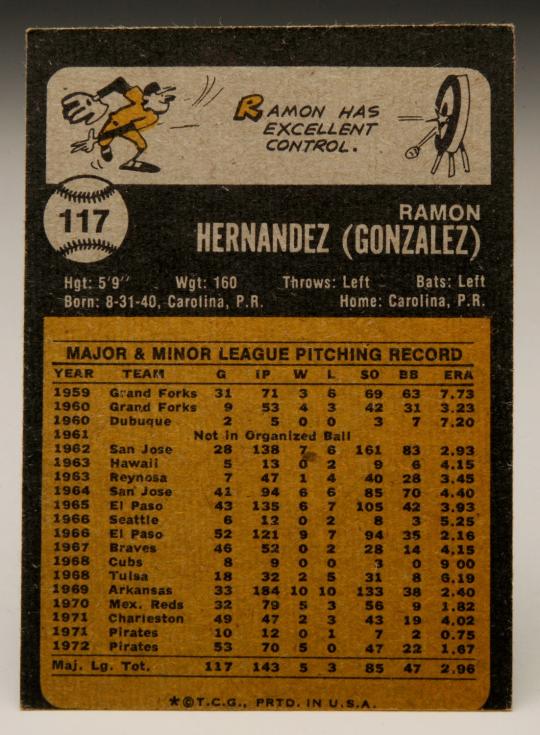

Originally signed by legendary Pirates scout Howie Haak out of his native Puerto Rico in the late 1950s, the 5-foot-9 left-hander bounced around from franchise to franchise before eventually making his way back to Pittsburgh. During the way, Hernandez made stops in the Los Angeles Angels and St. Louis Cardinals farm systems, and consumed cups of coffee with the Atlanta Braves and Chicago Cubs.

By the end of the 1960s, Hernandez had developed a controversial reputation around the baseball world. Most scouts scoffed at him because they believed him to be older than his listed age. The Cardinals gave up on him because they felt he didn’t put out enough effort in running drills. Some of his opponents felt he put out too much of an effort. As a baserunner in a 1969 minor league game, Hernandez spiked the other team’s third baseman, precipitating a bench-clearing brawl. During the fight, Hernandez pulled the base out of its moorings and began swinging it at other players.

Some of Hernandez’ managers considered him a disciplinary problem, especially Don Zimmer, who once managed him in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Zimmer was leery of Hernandez, who rarely smiled, said little to his teammates, and reportedly carried a gun with him. Hernandez also liked to test the manager’s patience by bending and breaking the rules. So infuriated by Hernandez’ flouting of team regulations, Zimmer vowed not to pitch the left-hander during the team’s late-season drive toward the Winter League playoffs.

Prior to the 1971 season, the Pirates acquired Hernandez from a Mexican League team, the Mexico City Reds, for an ever lesser-known minor league left-hander named Danilo “Danny” Rivas and $15,000 in cash. Pirates general manager Joe Brown made the trade based on a tip from his third baseman, Jose Pagan. “There is a pitcher who can help our club right away,” the respected Pagan told Brown. “I can’t understand why some big league club doesn’t give him a chance.”

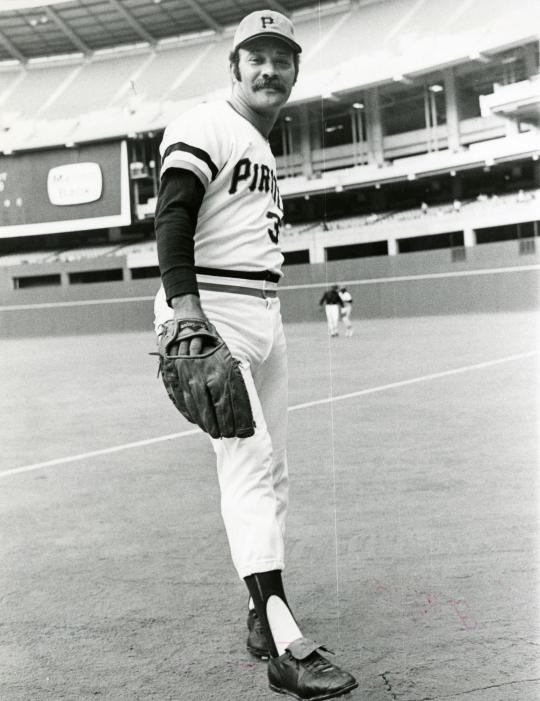

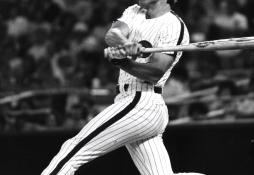

Other than Pagan and Brown, no one expected much from Hernandez, who had already turned 30. After beginning the 1971 season at Triple-A Charleston, Hernandez earned a midseason call-up. The little left-hander immediately drew the attention of fans and media with his twisting windup and slinky sidearming delivery. He had two effective pitches, a roundhouse curve and a funky screwball, along with pinpoint control.

Hernandez retired just about everyone he faced, at first left-handed batters, and then right-handers, too. Pirates fans took to him quickly, with younger ones imitating his unusual sidearm motion.

Hernandez pitched in only 10 games for the Pirates in 1971, but had the impact of a player who had spent the entire season in Pittsburgh. After helping the Bucs clinch the National League East with several clutch performances against the rival Cardinals in September, he found himself left off the postseason roster – the victim of a numbers game.

Undeterred, Hernandez went on to enjoy his best season in 1972. By the end of that summer, the stylish southpaw had emerged as the Bucs’ left-handed relief ace, with a 5-0 record, 14 saves, and an earned run average of 1.67, all accomplishments that helped the Pirates win their third straight Eastern Division title. (Among full-time National League relievers, only Jim Brewer of Los Angeles had a better ERA than Hernandez.) With his impeccable control and variety of moving pitches, several scouts considered Hernandez the league’s best reliever.

As Hernandez became an effective reliever with the Pirates, he also garnered a reputation as the silent man in the clubhouse. He rarely conversed with players and reporters. His fellow relievers good-naturedly kidded him in the Pirates’ bullpen, but Hernandez said little in response, perhaps in part because of his severe limitations with the English language. Or maybe he just wanted to be left in his own little corner of the world.

Although he remained quiet, Pirate players did not resent Hernandez at all. According to his countryman Roberto Clemente – who also happened to be fellow native of Carolina, a small town in Puerto Rico – Hernandez achieved a level of acceptance in the Pirates’ clubhouse. “The big thing about Hernandez is that he knows he is welcome here,” Clemente told Charley Feeney of the Sporting News. “He doesn’t speak English real good, but the players on this club let him know they like him, just by an occasional smile, or a jab in the ribs.”

Whereas Hernandez had struggled to fit in with other teams, he had found his niche in Pittsburgh. Joe Brown believed that the Pirates had just the right support system for Hernandez. “He’s a quiet person,” Brown told the Pittsburgh Press. “Most clubs don’t have as many Latin American ballplayers as we do. He feels at home here. He had two people in whom he has great confidence, Pagan and Clemente. He respects them and listens to them.”

In 1973 and ’74, Hernandez’ level of pitching fell from brilliant to merely outstanding. Still, among National League left-handers, no one pitched better.

Hernandez did not start to show real slippage until 1975 and ’76, convincing the Pirates to sell him to the Cubs. The move left the Pirates without a left-handed reliever for the final weeks of the ‘76 season.

Hernandez finished out the ’76 season at Wrigley Field, but he lasted less than two months into the ’77 season before the Cubs traded him to the Boston Red Sox for veteran outfielder Bobby Darwin. After initially balking at reporting to Beantown, Hernandez decided to report to his new team. He struggled in most of his 12 appearances with the Sox, thereby ending his major league career. He then went back to Puerto Rico, where he pitched winter ball for several seasons.

And just as quietly as Hernandez had emerged on the Pirates’ scene in 1971, he faded silently into baseball oblivion. He never went to work for a major league organization, didn’t become a pitching coach or a scout, remaining completely anonymous and out of the public spotlight for 32 years.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum