- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty

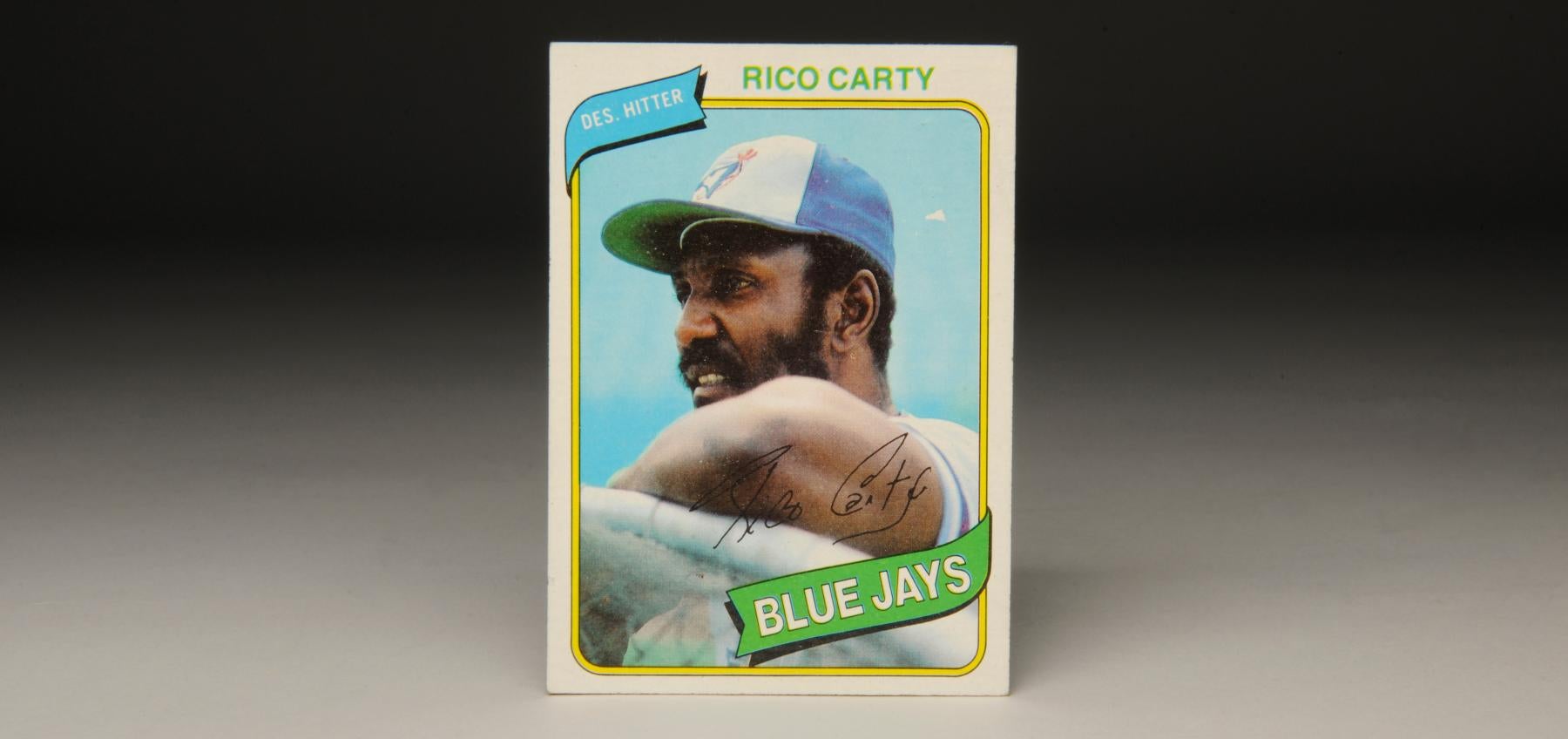

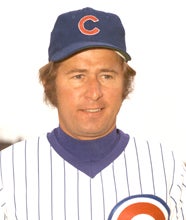

This 1980 Topps card was the last of Rico Carty’s career. By the time this photograph was taken (likely sometime in the spring of 1979), Carty had taken on the look of a grizzled, well-worn veteran. A few wrinkles appeared on his face, along with the lengthy sideburns and full mustache that became so fashionable in 1970s baseball.

Beyond his physical appearance, Carty takes a pose that epitomizes the posture of the wise veteran. With his left arm draped on the railing, Carty is gazing toward the playing field with that all-knowing look that has seen so much during a 15-year career that included stops with six different franchises. He looks like a leader, an ancient veteran whom his younger teammates can call upon for sage advice and counsel.

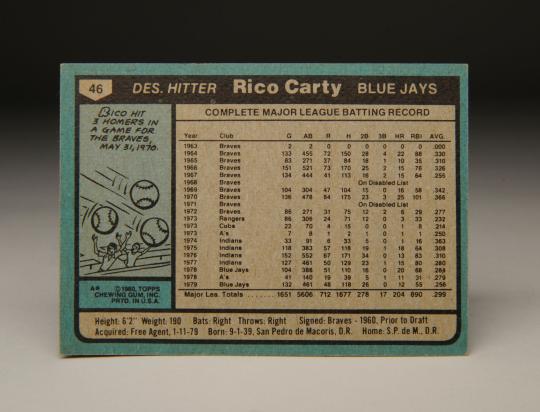

As it turns out, Carty did not actually play in 1980, the year that this Topps card was published. He was expected to do some DHing and some pinch-hitting for the Toronto Blue Jays that summer, but age finally caught up with the veteran hitter and his chronically sore knees. (As Carty’s former manager, Whitey Herzog, once said, the team trainer had “seen better knees on a camel.”) On March 29, during the final days of spring training, the Jays decided that the 40-year-old Carty could no longer help them. They released him, ending a professional career that had begun 21 years earlier.

In many ways, Carty’s career can be filed into the category of “what might have been.” If not for a ridiculously long series of injuries and illnesses, Carty might have made it to the Hall of Fame. As it was, too many physical setbacks prevented him from compiling a resume worthy of Cooperstown.

Yet, there is much more to the Carty story than his inability to reach his superstar potential. Even without recognition as an all-time great, Carty remains one of the most fascinating athletes of the expansion era.

Prior to becoming a professional ballplayer, the solidly-built Carty starred in the boxing ring. Although the two sports require far different skills, Carty found common ground in one area: his ability to hit, first his opponents in the ring and then live pitching.

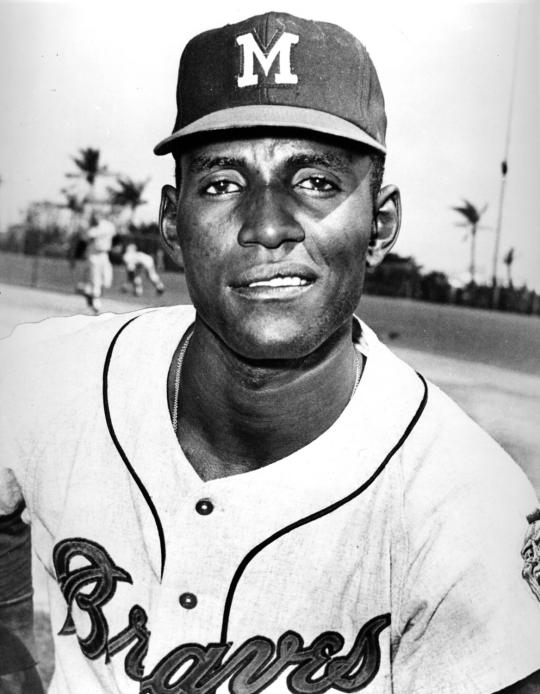

The start of Carty’s professional career in baseball did not come without controversy. As a young player out of the Dominican Republic, Carty had signed agreements with 10 different major league organizations. With multiple contracts in hand, the president of the National Association, George Trautman, was forced to step in. Trautman could have suspended Carty, but he took a more lenient approach, allowing Carty to choose which organization he preferred. Carty told Trautman that he wanted to play for the Milwaukee Braves. Trautman said yes to that, allowing Carty to being his pro career as a catcher in Davenport, Iowa, in 1960.

Carty struggled as a minor league rookie, perhaps in part because of his limitations with the language. “In 1960, when I came up from the Dominican Republic, I couldn’t speak English,” Carty would later tell Cleveland sportswriter Bob Nold. “Every time anyone would say something that I didn’t understand, I wanted to fight right away.”

The following year, Carty moved on to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, of the Northwest League and began to hit for both average and power. He quickly emerged as one of the top hitting prospects in the organization. While his hitting was stellar, he struggled with the defensive requirements of catching. In 1964, the Braves moved Carty from catcher to the outfield, a move that coincided with his rookie season in Milwaukee. Emerging as the Braves’ everyday left fielder, Carty had his way with National League pitching, batting .330 with a .554 slugging percentage. If not for the presence of a young Richie Allen in Philadelphia, Carty would have won the Rookie of the Year Award.

It was during the spring of ’64 that Carty came in contact with Braves hitting coach Dixie Walker, the onetime star of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Walker worked with Carty on his two-strike approach, convincing him to choke up on the bat three inches and not commit to any one pitch. Carty took the advice and ran with it. Within a few years, Carty would gain a reputation as the as the best two-strike hitter of his era.

Still, there were setbacks along the way. In his sophomore season of 1965, Carty injured his back; the ailment forced him to miss half of the season. In the spring of 1968, Carty contracted tuberculosis, rendering him unavailable to play the entire season. It would have been Carty’s age 28 season, right in the middle of his physical prime, but the bout with TB wiped out what could have been an MVP-caliber campaign.

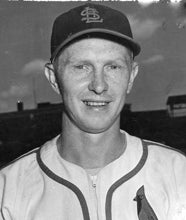

As he recuperated from the disease, Carty received a kind letter of encouragement from Hall of Famer Red Schoendienst, who was managing the St. Louis Cardinals at the time. Recalling his own successful battle with tuberculous, which he contracted after the 1958 season, Schoendienst offered Carty the following words of support: “I hope you continue to battle the TB in the fine manner in which you battled your opponents in the past several seasons.”

Carty did just that. In 1969, he bounced back to appear in 104 games, hitting a rousing .342. By 1970, Carty had fully regained his strength. He led the National League with a .366 batting average and a .454 on-base percentage. He reached career highs with 25 home runs and 101 RBIs. He also made the All-Star team as a write-in candidate, the first of only two players in history who could make such a boast.

Then, during the offseason, Carty’s career came to a crossroads. During a winter league game, he collided with fellow Dominican outfielder Matty Alou. The incident resulted in three fractures in his left kneecap, along with torn muscles in his leg. After surgery was performed, Carty had to wear an orthopedic brace for the next eight months; he also developed a blood clot in the knee. For the second time in his career, Carty sat on the sidelines all summer long.

Even after the brace was removed, Carty encountered other problems in 1971. He and his brother-in-law were stopped in their car at a traffic light when two plainclothes policemen approached their vehicle. Soon after, a third policeman came by. Mistaken as the suspects in the recent murder of two police officers, Carty and his brother-in-law, Carlos Ramirez, sustained a horrific beating. According to Carty, one of the plainclothes officers hit him in the nose with a black jack.

The attack left Carty’s vision impaired. If his eyesight didn’t improve, he vowed to sue the Atlanta police department. Thankfully, his sight returned to its original level, and he dropped the idea of a lawsuit. He also chose not to press charges. The city, however, felt otherwise and suspended the three policemen. Over 50 witnesses came to testify in support of Carty and Ramirez.

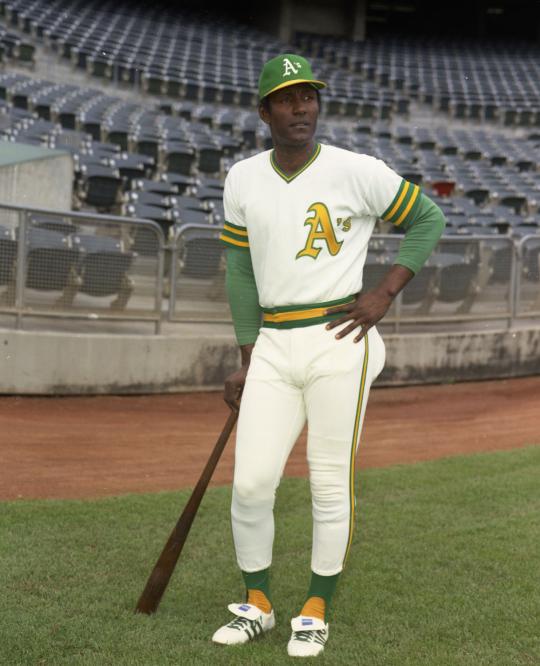

While Carty was an innocent victim in the incident, there were times that he also found himself in conflict with his teammates. During his years with the Braves, Carty twice traded punches with teammates. So after the 1972 season, the Braves dealt with the situation by trading him to the Texas Rangers. While in Texas, Carty verbally sparred with his manager, which resulted in an abrupt mid-season departure. The Rangers traded him back to the National League, this time sending him to the Chicago Cubs. Carty proceeded to clash with Ron Santo, one of the Cubs’ senior veterans and most prominent clubhouse leaders. Within a few weeks, the Cubs traded him back to the American League, where he landed with the Oakland A’s.

Carty’s brutal honesty and his willingness to confront teammates and managers sometimes created controversy, but he could be colorful in a good way, too. Outgoing and funny, he proudly called himself the “Beeg Boy,” using his heavy Spanish accent to change the pronunciation of the word “Big.” Later, when some of his teammates told him not to refer to himself as a boy, he changed his nickname to “Beeg Mon.”

Carty developed a strong relationship with fans, particularly during his years in Atlanta. Always sporting a smile, he often waved to fans in the stands, throwing balls to them before and during the game. He also spent a good portion of his pre-game time signing autographs, sometimes for more than half an hour at a clip. In response, a number of his fans banded together to form “Carty’s Corner,” located in the left field bleachers of Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium.

On the field, Carty brandished a distinctive style. Unlike most players, he chose not to take a practice swing, either before stepping into the batter’s box or during the course of his at-bat. In contrast to many hitters who step out and tug at their uniforms between pitches, Carty stood firmly planted in the batter’s box throughout each turn at bat. He remained virtually motionless, all the while glaring at the opposing pitcher. Given his enormous hitting talents, Carty’s rigid stance and death stare must have made him more intimidating to rival hurlers.

Carty’s hitting talent seemed like it might go to waste after his tumultuous 1973 season. The A’s released him, and no other teams showed much interest. Topps did not even issue a card for Carty as part of its 1974 set. Left with few alternatives, Carty decided to remake himself in the Mexican League, which was considered roughly the equivalent of Double-A minor league ball at the time.

Regaining his health and his batting stroke in Mexico, Carty drew the interest of the Cleveland Indians, who signed him late in 1974. He revived his career as a designated hitter and first baseman, hitting .363 in 33 games for the Indians that summer.

Settling into a comfortable role as the Indians’ DH, Carty put together three more productive seasons with Cleveland. Along the way, the first-year Blue Jays took him in the expansion draft, but the Indians considered him so valuable that they almost immediately reacquired him, sending catcher Rick Cerone and outfielder John Lowenstein to Toronto in a three-man trade.

During the spring of 1978, the Indians decided to make themselves younger by trading Carty to the Blue Jays for a minor league pitching prospect. Carty would later spend some time in Oakland, finishing out the season with a combined 31 home runs, before returning to Toronto in 1979.

In some ways, Carty’s remarkable hitting skills and off-the-field melodramas overshadowed his intelligence. After he retired from baseball, he became a politician in his native Dominican Republic. In May of 1994, he was elected mayor of his hometown of San Pedro de Macoris and was scheduled to be sworn in, only to have a call for a recount. On August 2, the recount gave the job to Carty’s principal opponent.

If Carty had won the election, he had planned to repair many of the city’s decaying streets and step up efforts to fight pollution. He also wanted to ask the United States for help in bringing baseball equipment to the Dominican Republic. His plans represented a continuation of something he had done during his playing days; in 1965, he had traveled with Catholic Relief Services to the Dominican in an effort to deliver food and other needed supplies to his militarized country.

In retrospect, Carty was glad that his political career did not work out. “I didn’t like politics,” he once told MLB.com. “You have to lie too much.” Instead, Carty became something of a baseball ambassador in his native Dominican Republic. Living and working in San Pedro de Macoris, he mentored many young stars, including Alfonso Soriano and Robinson Canó, before passing away on Nov. 23, 2024.

Much like his 1980 Topps card shows him to be, Rico Carty took on the role of the wise old baseball man.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum