- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

As someone who grew up in the 1970s, I’ve always loved wood paneling in a home. I even appreciate the cheap, cardboard-thin wood that lined the basements of many houses in the northeast during the seventies. Given such affection for wood paneling, it’s not surprising that Topps’ 1987 wood-bordered set ranks as one of my favorite sets of the 1980s.

Topps’ 1987 release was not the company’s first venture into wood borders. Twenty five years earlier, in the spring of 1962, Topps put out its first wood-grain set. The cards featured thin borders all the way around, but Topps peeled back the photo in the lower right-hand corner, allowing more room for the wood background and a place to insert the name of the player and his team. The 1962 cards, with their distinctive look, became a hit with collectors.

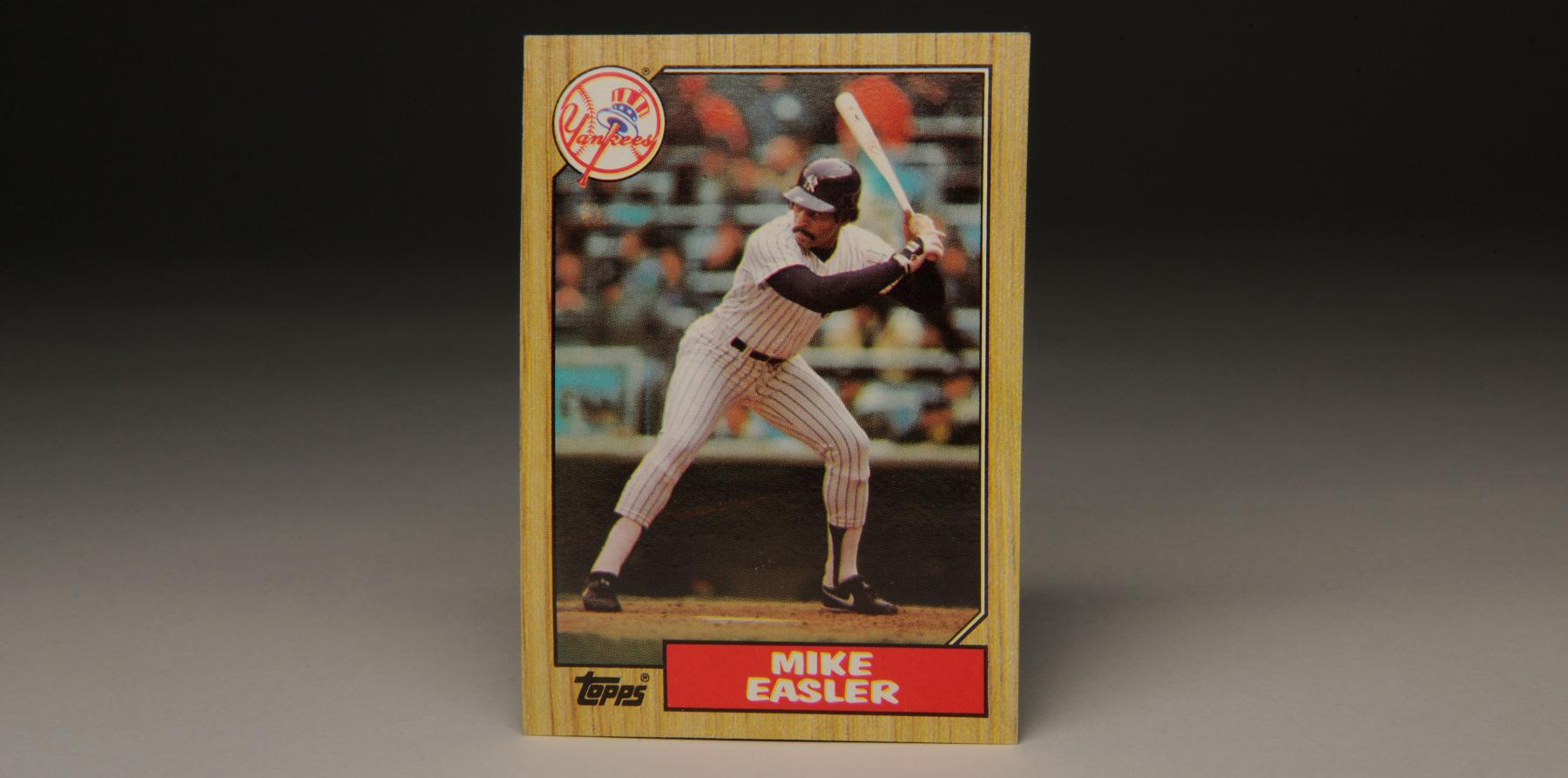

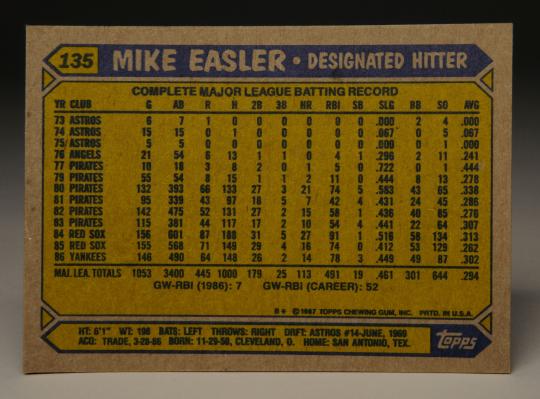

With a new wood border providing an ideal framework, Mike Easler’s card rates near the top of the list in 1987. Taken on a cloudy afternoon at Yankee Stadium sometime during the 1986 season, the photograph of Easler is crisp and clear. The card, No. 135 in the set, gives us a head-on view of Easler’s memorable batting stance. Unlike most power hitters, Easler batted out of a pronounced crouch, a pose usually preferred by singles and doubles hitters.

After attacking a pitcher’s offering with a fierce uppercut, Easler finished off each swing with his signature flourish—an exaggerated rotation of the bat, the equivalent of a helicopter motion. Even as college students in the 1980s, we used to mimic the Easler “helicopter” during meetings with fellow baseball diehards. No one of Easler’s era finished his swing in such a way, and no one since has matched Easler’s twirling of the bat.

In addition to his distinctive batting style, Easler also had a descriptive nickname. Although most New York Yankee fans remember Don Mattingly as “The Hit Man,” he was actually not the first to acquire the nickname. It was Easler who preceded Mattingly as the original Hit Man, a testament to his aggressive style at the plate and his ability to pepper line drives from one outfield gap to another. Unlike most left-handed hitters with power, Easler boasted a particularly effective opposite-field stroke, which he seemed to prefer over pulling the ball to right field. Easler was usually at his best hitting the ball with gusto toward left-center, an ability that he honed during his years with the Boston Red Sox. Easler became particularly adept at hitting “The Wall” at Fenway Park.

Unfortunately, Easler would lose that advantage during his two stints with the Yankees. Left field at the old Yankee Stadium did not provide a reachable target for most left-handed hitters. The dimensions of “Death Valley,” as it used to be call, made life difficult for Easler, who struggled to fill the shoes of the player for whom he was traded, Don Baylor.

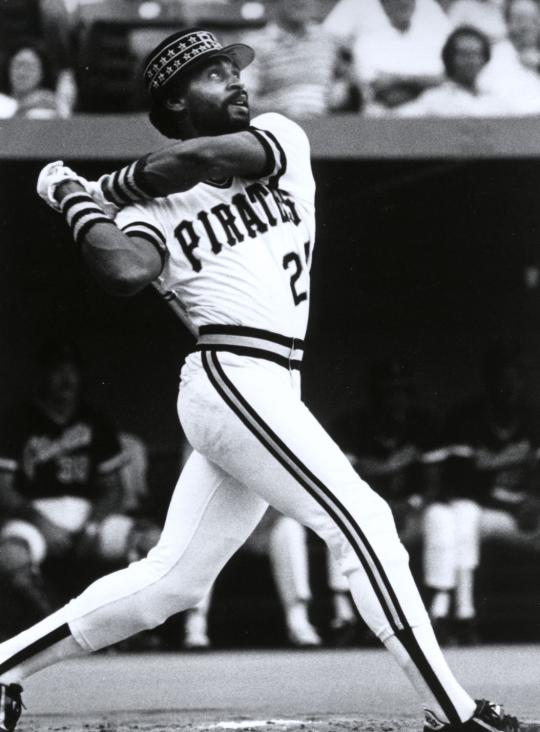

Still, Easler was reasonably productive in his first go-round in Yankee pinstripes. He played well as a platoon DH and left fielder, sustaining a role that he had filled with the Red Sox. Prior to that, Easler had forged a niche as a highly successful part-time player with the Pittsburgh Pirates, which included a cameo during the team’s World Championship season in 1979.

That Easler sustained a lasting major league career of consequence throughout the 1980s is testament to his perseverance. For most of the 1970s, Easler bided his time in the minor leagues. From 1969 to 1977, he spent time in the organizations of the Houston Astros, California Angels, St; Louis Cardinals, and the Pirates. Along the way, he won two minor league batting titles. Yet, major league scouts didn’t like Easler; they viewed him as nothing more than a platoon player, incapable of hitting left-handed pitching, and regarded him as a butcher in the outfield. They didn’t feel he hit with enough power or possessed enough speed. Even as Easler lambasted minor pitching at Double-A and Triple-A, scouts dismissed him as nothing more than a career minor leaguer.

Easler had three cups of coffee with the Astros and one with the Angels, never earning more than 54 at-bats in any one stint. He didn’t hit well in those abbreviated tenures, only cementing his reputation as a career minor leaguer. By April of 1977, he had already been traded three times.

Most players would have been excused for taking their minor league numbers to the Mexican League or the Far East for a bigger payday, but Easler remained adamant about a career in the major leagues. Easler’s persistence started to deliver dividends in September of 1977, when the Pirates brought him up as part of their expanded roster. Easler made a good impression in 10 games, hitting .444 with a home run in 18 at-bats.

Easler’s September performance opened some eyes, but the Pirates had so many good outfielders at the time that they had no room for him in 1978. So he went back to Triple-A Columbus and batted .330 with 18 home runs. It was clear that Easler had mastered minor league pitching and had nothing left to prove at the Triple-A level. As Easler would later say, these were “dark times.” He would refer to his last few years in the minor leagues as the “toughest years of my life.”

Easler’s patience finally paid off in 1979. Becoming one of the team’s bench players, he hit a respectable .278 in limited duty and earned a place on the team’s postseason roster. Appearing briefly in the playoffs and World Series, Easler earned himself a championship ring as the Pirates claimed their first title since 1971.

In 1980, Easler assumed a larger role. With Willie Stargell’s playing time affected by injuries and John Milner showing significant decline at the plate, Easler became the Pirates’ platoon left fielder. Alternating with veteran Bill Robinson, Easler feasted against National League pitching, hitting .338 with 21 home runs and 43 walks. He also greatly improved his fielding in left field, to the point where the Pirates stopped taking him out of games for defensive reasons. Finally, after a long climb that had begun in 1969, Easler had convinced the Pirates that he belonged.

Easler would remain a productive player for the Pirates over the next three seasons, even earning selection to the All-Star Game during the strike-shortened season of 1981. Easler also helped his cause by becoming popular in the Pirates’ clubhouse. Teammates liked him, as did the media. Easler always answered questions from the press after games, regardless of whether the Pirates won or lost, regardless of whether Easler went 4-for-4 or 0-for-4. His willingness to talk became especially important when he joined the Red Sox later in the 1980s. At the time, the Red Sox had a reputation for a difficult clubhouse, where some players did not like to meet with the media, especially after hard losses. Even the most jaded Red Sox reporter could find solace at Easler’s locker. Friendly and accessible to an extreme, Easler would always talk—no matter what.

After two productive seasons with the Sox, Easler moved on to New York in the trade for Baylor. When asked about the controversy that always seemed to swirl around the Yankees at the time, Easler did his best to remain above the fray. “I’m a nice guy,” Easler told the Albany Times Union in the spring of 1986. “As far as I’m concerned, I’ve got this uniform on and I’m going to go out there and do my job. I’m going to see the baseball and hit it. Whack!”

The Hit Man did just that for the Yankees, hitting .302 with 14 home runs as a productive left-handed DH. But the team’s need for pitching resulted in an unpopular offseason trade to the Philadelphia Phillies, this time for right-hander Charles Hudson. And then just a few months into his stay in the City of Brotherly Love, the Yankees decided that they had to have him back. On June 10, 1987, the Yankees reacquired Easler for two borderline minor league prospects, allowing him to finish out the season—and his major league career—in the Bronx. From there, Easler took his live bat to the Japanese Leagues, where he hit well over the next two seasons while making a new group of friends.

Easler didn’t play long for the Yankees—less than two full seasons—but he managed to become popular with his New York teammates and fans. Given his sociable manner, his dynamic hitting style, and his relentless determination to make the major leagues, it’s easy to see why Easler became such a cult favorite during the 1980s. His 1987 Topps card might not be worth much—it’s a common card from an era in which too many cards were produced to begin with—but it’s still a nice one to have.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum