- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1991 Topps Mariano Duncan

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Mariano Duncan

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

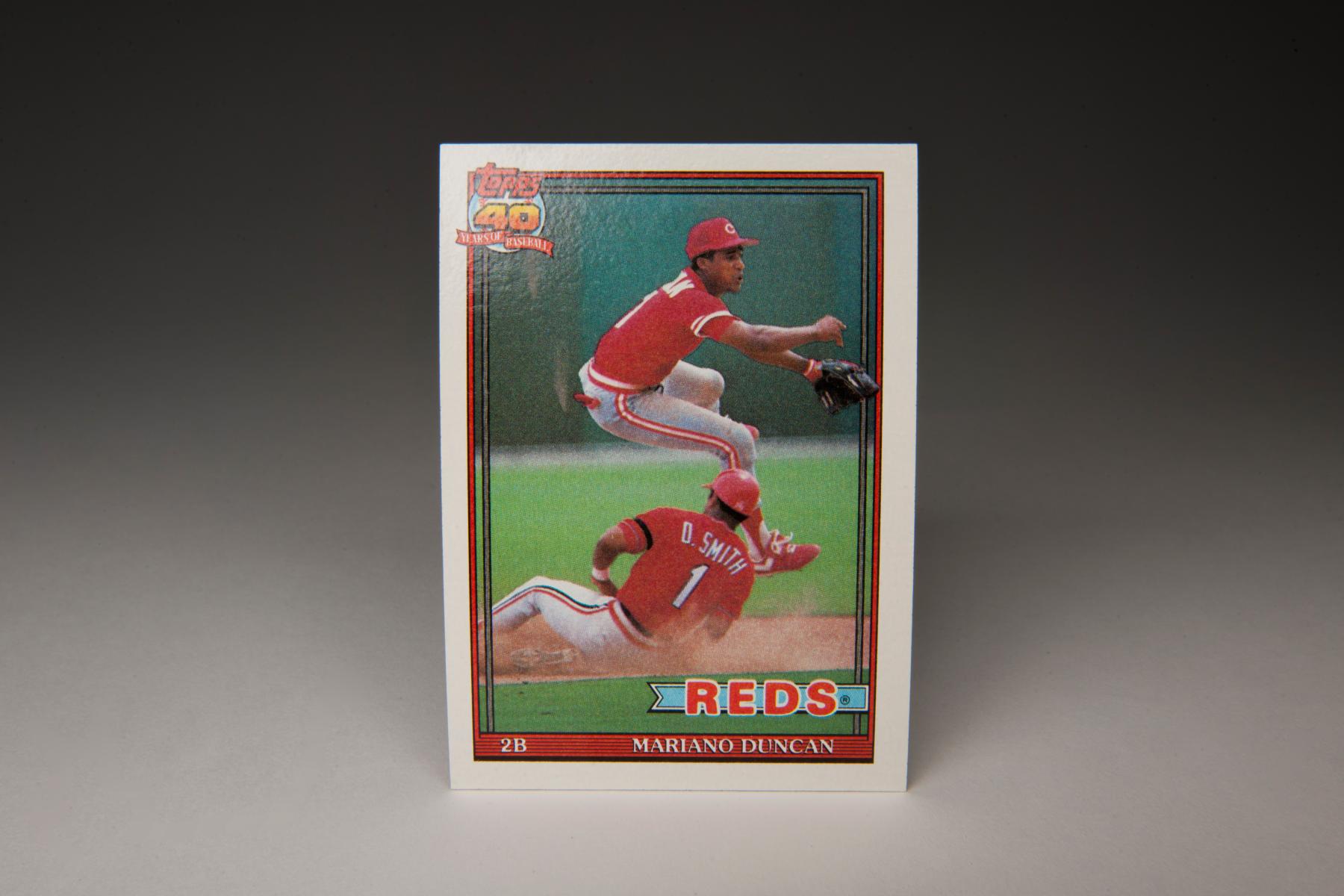

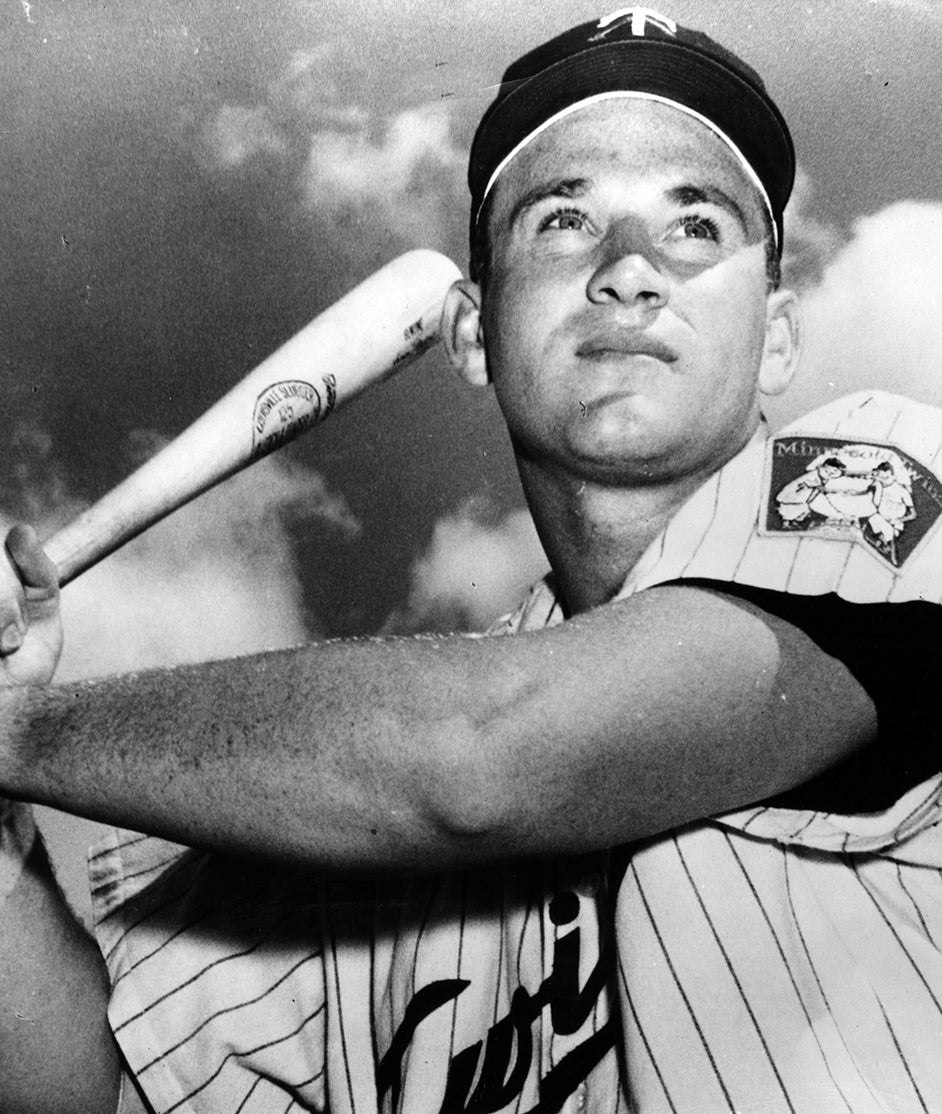

There is so much happening on Mariano Duncan’s 1991 Topps card that it’s difficult to know where to begin. I suppose we could start with the perfect timing of the photograph, which captures Duncan right in the middle of his leap, as he avoids a takeout slide at second base. The player who is sliding into second base is none other than Ozzie Smith, making this one of those rare cards where the “background” player is actually far more famous than the featured player. (For other examples of this, see Reggie Smith’s 1983 Topps card (which features a cameo by Ryne Sandberg) or John Ellis’ 1972 Topps card (where Harmon Killebrew occupies as much space as Ellis himself).

As much as the action photography and the presence of a Hall of Famer dominate the card, there’s also an oddity at work here. Notice that both Duncan and Smith are wearing red jerseys, even though they are clearly playing for opposing teams. This almost certainly would not be allowed in a regular season game, because of the confusion that would be created for fans, particularly for those watching from a good distance away. If it’s not a regular season game - and I’m almost certain it isn’t - then it must be from a Spring Training game played in Florida. Photographs from spring exhibition games are certainly not unusual on Topps cards, but they are rarer than regular season game photographs or even posed shots from the sidelines taken before games.

Still, there’s even more going on with this unusual card. Let’s take a closer look at the figure of Duncan. There seems to be a small black line outlining the back side of his jersey. It doesn’t look quite right. It almost appears as if a separate photo of Duncan is being superimposed onto a photograph of Smith. I’m not sure why Topps would do that, but it has the effect of a “green screen” technology that is used in Hollywood. It doesn’t quite look natural; if anything, it creates a surreal effect of Duncan being superimposed onto the outfield wall. It’s a little strange, to say the least, and only makes an intriguing card all the more curious.

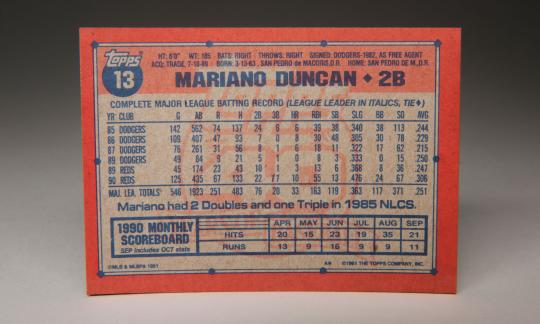

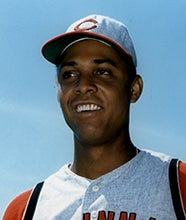

All things considered, there’s far more than meets the eye on this common card from the 1991 Topps set. The same could be said of Duncan. On the surface, he was a relatively productive player over a 12-year career that included stints with the Reds, Los Angeles Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, New York Yankees and Toronto Blue Jays. But there’s much more substantial to Duncan, from his role as an inspirational leader to his habit of playing at his best for world championship teams.

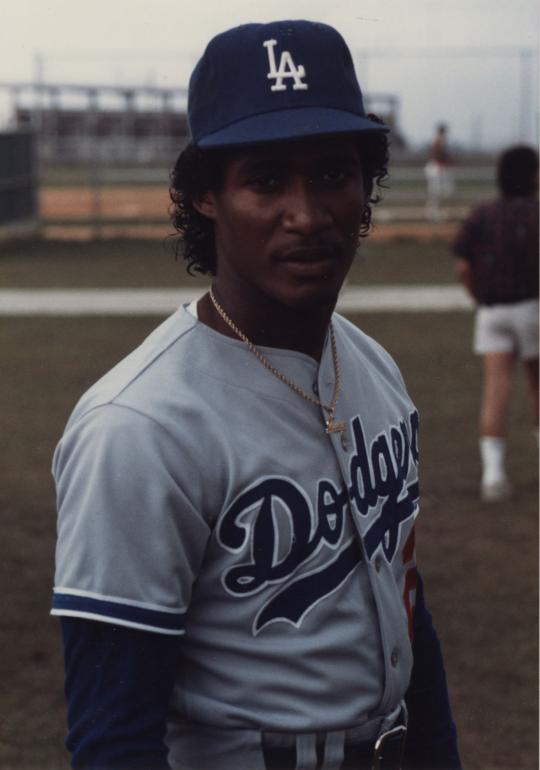

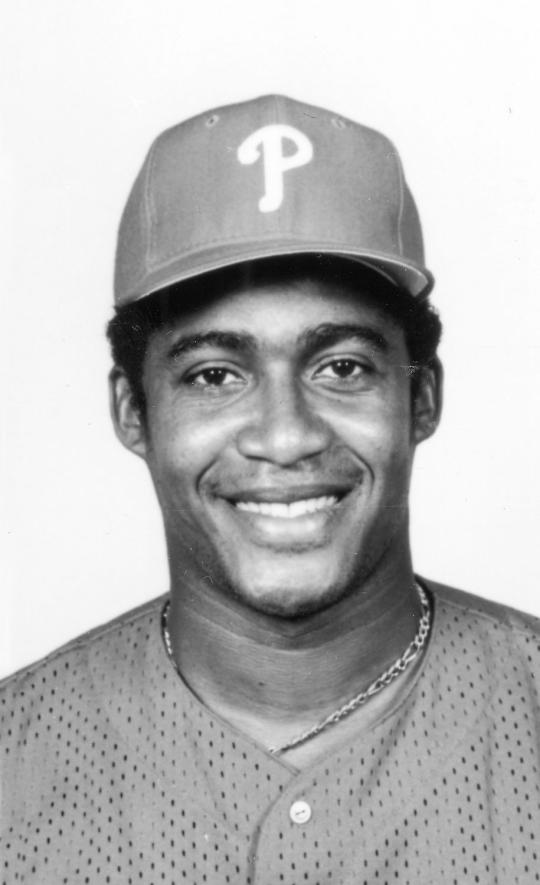

One of many MLB shortstops to emerge from the small Dominican city of San Pedro de Macoris, Duncan signed with the Dodgers as an amateur free agent in 1982. Only three years later, he made the Dodgers’ roster, becoming their starting shortstop. He hit only .244 with no power as a rookie, but his range and fielding made him so valuable that the baseball writers gave him some MVP votes and ranked him as the third best rookie of the Class of 1985.

Duncan’s hitting failed to improve over the next two seasons. That lack of development, along with some erratic fielding, resulted in a return to the minor leagues for all of 1988. As a result, Duncan missed out on what would have been his first World Series ring. Duncan also experimented with switch-hitting, something the Dodgers felt would be prudent as a way of taking advantage of his speed, but he struggled with his new left-handed hitting stroke. By the middle of the 1989 season, the Dodgers included him in a trade package sent to Cincinnati for outfielder Kal Daniels and utility infielder Lenny Harris.

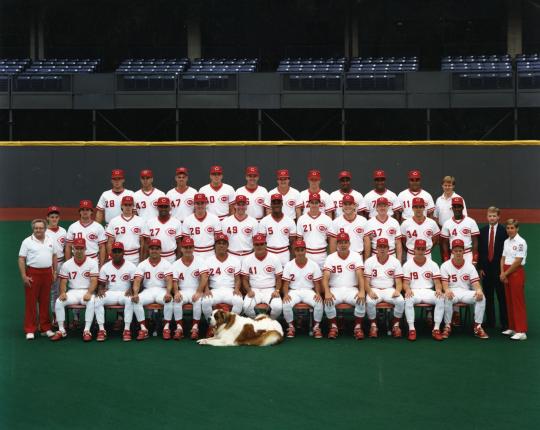

It did not take long for Duncan to become comfortable in Cincinnati. And in 1990, Duncan received another break that his career needed. The Reds made Lou Piniella their manager, replacing interim skipper Tommy Helms, who had succeeded the suspended Pete Rose during the tumultuous summer of 1989. Duncan put in some remedial work with Piniella and Reds hitting instructor Tony Perez, their onetime first baseman and future Hall of Famer. At the start of Spring Training in 1990, Piniella announced that Duncan would replace Ron Oester as the Reds’ starting second baseman. Duncan responded well; he hit .309 with 10 home runs and 11 triples as the Reds won the National League West. He then hit .300 in the Championship Series, as the Reds defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates on their way to a world championship.

After a down year in 1991, the Reds let Duncan depart via free agency. He signed a contract with the Phillies, where he became a jack-of-all-trades, filling in as a left fielder, second baseman, shortstop and third baseman. He didn’t hit much (.267 with only 18 walks), but his versatility and speed gave him some value.

As usual, Duncan’s best performance in Philadelphia coincided with the team’s emergence as a contender. In 1993, the Phillies surprised the baseball world by winning 97 games and taking the National League East title. Duncan became a platoon second baseman (alternating with Mickey Morandini) and part-time shortstop, and flashed the ability the Reds had seen in 1990. Hitting .282 with 11 home runs in 124 games, Duncan surfaced as a key role player for manager Jim Fregosi. The Phillies advanced to the World Series, where Duncan hit .345, albeit in a losing cause to Joe Carter and the Toronto Blue Jays.

Duncan played all of the strike-shortened 1994 season in Philadelphia, garnering the only All-Star Game berth of his career, and then put up a .286 batting average over his first 52 games in 1995. Then in August, the Phillies placed him on waivers, seemingly as part of an effort to trade him to a contending team. The Reds put in a claim, but rather than negotiate a trade, the Phillies simply let him return to Cincinnati without player compensation in return. Appearing in 29 games for the contending Reds, Duncan put up an OPS of .807, helping Cincinnati to a division title.

After appearing sparingly in the Division Series and Championship Series, Duncan became a free agent for the second time in his career. In the meantime, the Yankees lost Randy Velarde to free agency, creating a hole in their middle infield scheme. The Yankees responded by signing Duncan, but the move was not met with enthusiasm from the media. But the media was wrong.

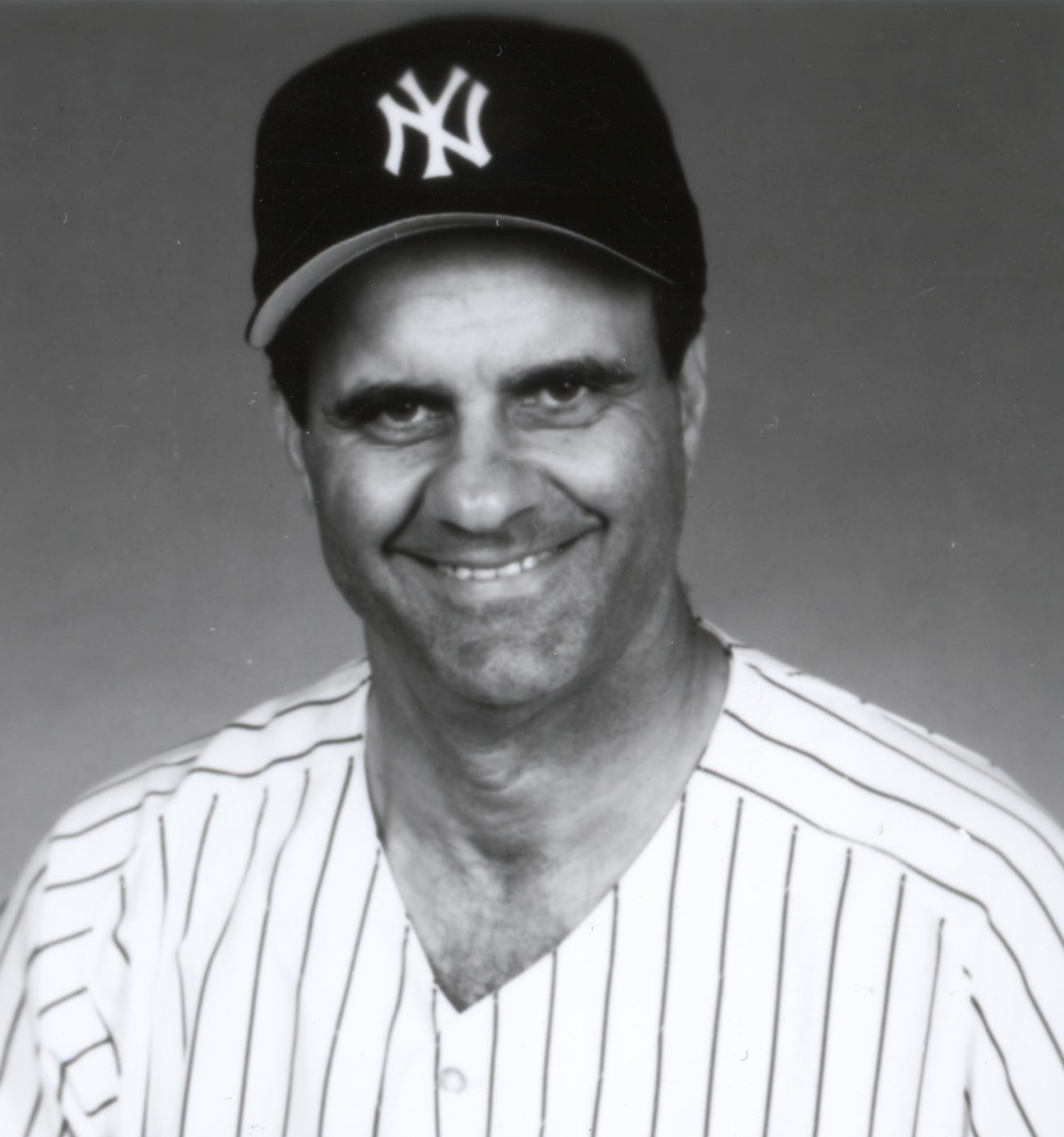

Initially, the Yankees targeted Duncan to fill a role as a utility infielder. But that plan changed quickly when veteran Tony Fernandez injured his elbow severely during spring training, forcing him to miss the entire season. Another option at second base, Pat Kelly, went down with a sore shoulder. Joe Torre, in his first season as Yankee manager, approached Duncan to tell him of his updated status. Torre also informed the veteran infielder of another role that he needed him to perform.

“Mariano, for now, you’re my starting second baseman,” Torre told Duncan. “You know Derek Jeter is our shortstop and I want you to go ahead and take care of that guy.” Duncan became a mentor to Jeter, taking him out to dinner, accompanying him on visits to local night spots, and offering him as much advice as the rookie could absorb.

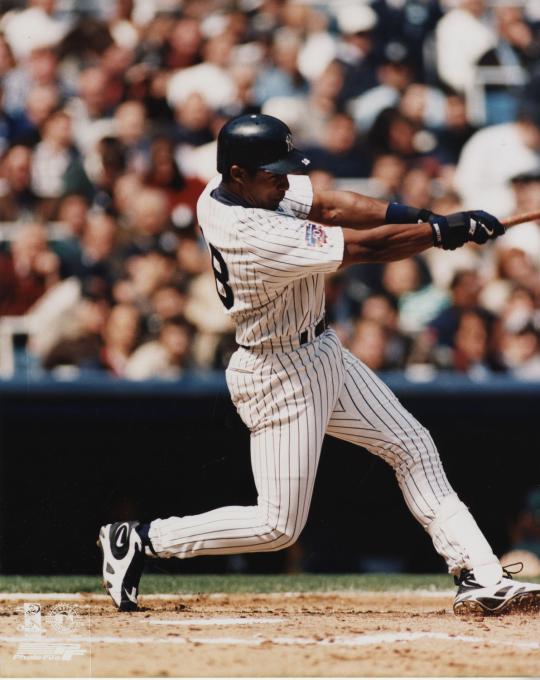

Due to the injuries to Fernandez and Kelly, Duncan emerged as the Yankees’ Opening Day second baseman. He also put forth the best season of his career. Playing in 106 games, he hit .340 and slugged an even .500, giving the Yankees some of their best production at the position since the days of Willie Randolph.

Duncan remained a free swinger; he drew only nine walks that season. But he still reached base 35 percent of the time. Defensively, his range had diminished, but he had become sure-handed and steady in turning the double play.

On a team that featured massive talents like Jeter, Bernie Williams, and Paul O’Neill, it was Duncan who emerged as one of the leaders. He instilled in his teammates a desire to work hard, play with maximum effort, and do whatever necessary to win the game that night. It was Duncan who crafted the catchy new slogan that was repeated by his teammates and reflected his Spanish accent: “We play today, we win today… das it.” Under their uniform jerseys, some of the Yankees wore T-shirts carrying those words, which became the mantra for a businesslike team that was light on fluff and heavy on playing the game hard and smart.

With players like Duncan setting the tone, the Yankees won 92 games on their way to an American League East title. Duncan then hit .313 in the Division Series, before slumping in the Championship Series and World Series. But Duncan’s postseason struggles mattered little in the grand scheme, as the Yankees rallied from two games down to win the world championship over the favored Atlanta Braves.

No one expected Duncan to match his 1996 numbers again, so it was no great surprise that he slumped the following summer. With his batting average in the .240s and the second base job now in the hands of fellow veteran Luis Sojo, Duncan sat on the bench and asked the Yankees to trade him. In late July, the Yankees finally did just that, sending him to the Blue Jays for a minor league outfielder named Angel Ramirez. Duncan closed out the season with Toronto, where he didn’t hit much. At season’s end, he again became a free agent and opted for a contract in the Japanese Leagues. He struggled in his one season in the Far East and returned to the states to make comeback attempts with the Florida Marlins and the New York Mets, but never made it back to the big leagues. By the end of the 1999 season, Duncan had called it quits.

Duncan hasn’t played the game in more 15 years, but remains active as a coach. With the Dodgers, he served as first base coach under Joe Torre, who remembered exactly what Duncan had meant to the Yankees years earlier. Fluent in both English and Spanish, Duncan is able to communicate equally with Latino players and those raised in the states. He currently uses those communications skills with the Chicago Cubs, where he works as one of their minor league hitting coaches in Class A ball. Toiling in the shadows of the lower minors, he has instructed top prospects like Kris Bryant, Javier Baez, and Jorge Soler - all huge contributors to the Cubs’ successful assault on a wild card spot this past season.

That’s how Duncan seems to like doing things, without fanfare or without recognition. Just as he quietly helped teams like the ’90 Reds, the ’93 Phillies, and the ’96 Yankees, all while bigger stars received most of the glory and the credit, Duncan just wants to make it easier for his minor league teams - and his players - to succeed as much as possible.

“We play today, we win today… das it.” They are words that Mariano Duncan made famous - and a philosophy that he continues to teach to this day.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame