- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Mayberry

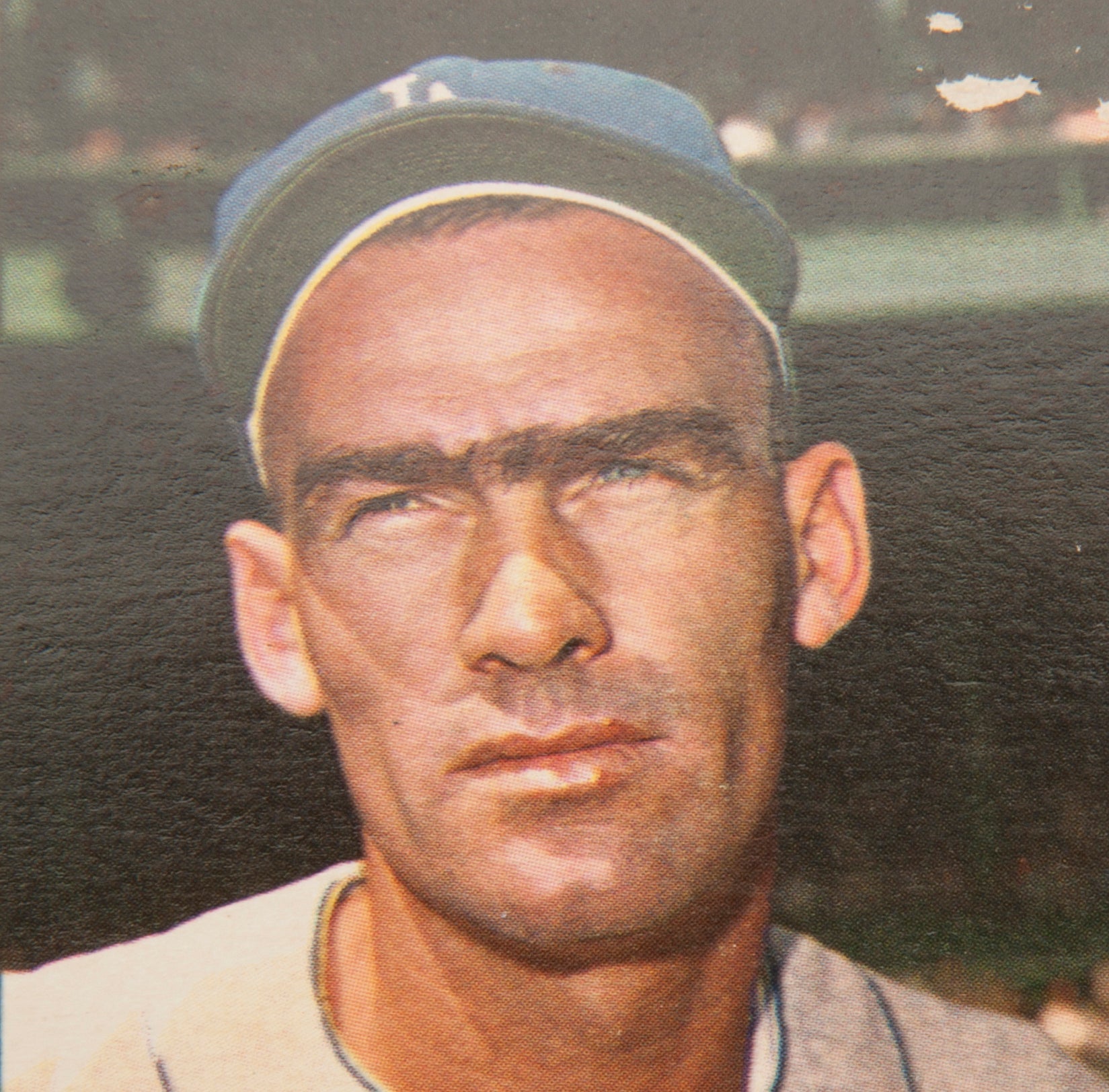

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Mayberry

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Back in 2009, former big league slugger John Mayberry became embroiled in one of the funniest bits of unintended humor that season. During a nationally televised broadcast of a Saturday afternoon game, FOX broadcasters mistook a Panamanian gentleman for Mayberry in the stands at Yankee Stadium. The FOX cameras cut repeatedly to the man, who could be seen talking on his cell phone, while the broadcasters continued to refer to him as the elder Mayberry.

Thankfully, the mistake was rectified. FOX broadcaster Ken Rosenthal then caught up with the real Mayberry, who happened to be at the game but was sitting in a different part of the Stadium. He was attending that day to watch his son, John Mayberry, Jr., make his major league debut for the Philadelphia Phillies. The younger Mayberry had just hit a three-run homer, prompting FOX to cut to the Mayberry “imposter” in the stands.

The real Mayberry took the case of misidentification with a good sense of humor. After all, it was an honest mistake -- and a light-hearted one at that. In a way, though, it’s unfortunate that the legacy of the elder Mayberry remains obscure -- because Mayberry was one of the top left-handed power hitters of the mid-1970s.

Emerging as a top prospect in the Houston Astros’ organization during the late 1960s, John Claiborne Mayberry found his path to the major leagues impeded by first basemen like Rusty Staub, Curt Blefary and Bob Watson. For four straight years, Mayberry split his time between the Astros and their minor league affiliates. He played only sporadically, and when he did play, he didn’t hit. During the 1971 season, the Astros tried to make him a slap hitter. A 235-pound slap hitter? It didn’t make much sense -- and it didn’t work either.

At the 1971 winter meetings, the Astros decided to revamp their roster. On November 29, they executed a blockbuster trade with the Cincinnati Reds, acquiring slugging first baseman Lee May while surrendering second baseman Joe Morgan as part of a massive eight-player deal. With May now on the roster and no room for their young power protégé, the Astros made a follow-up trade just days later. They sent Mayberry to the Kansas City Royals for two pitching prospects, Jim York and Lance Clemons.

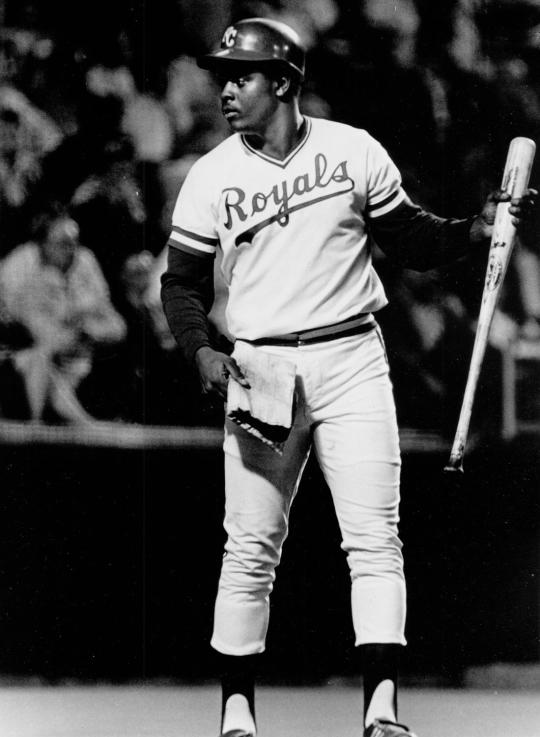

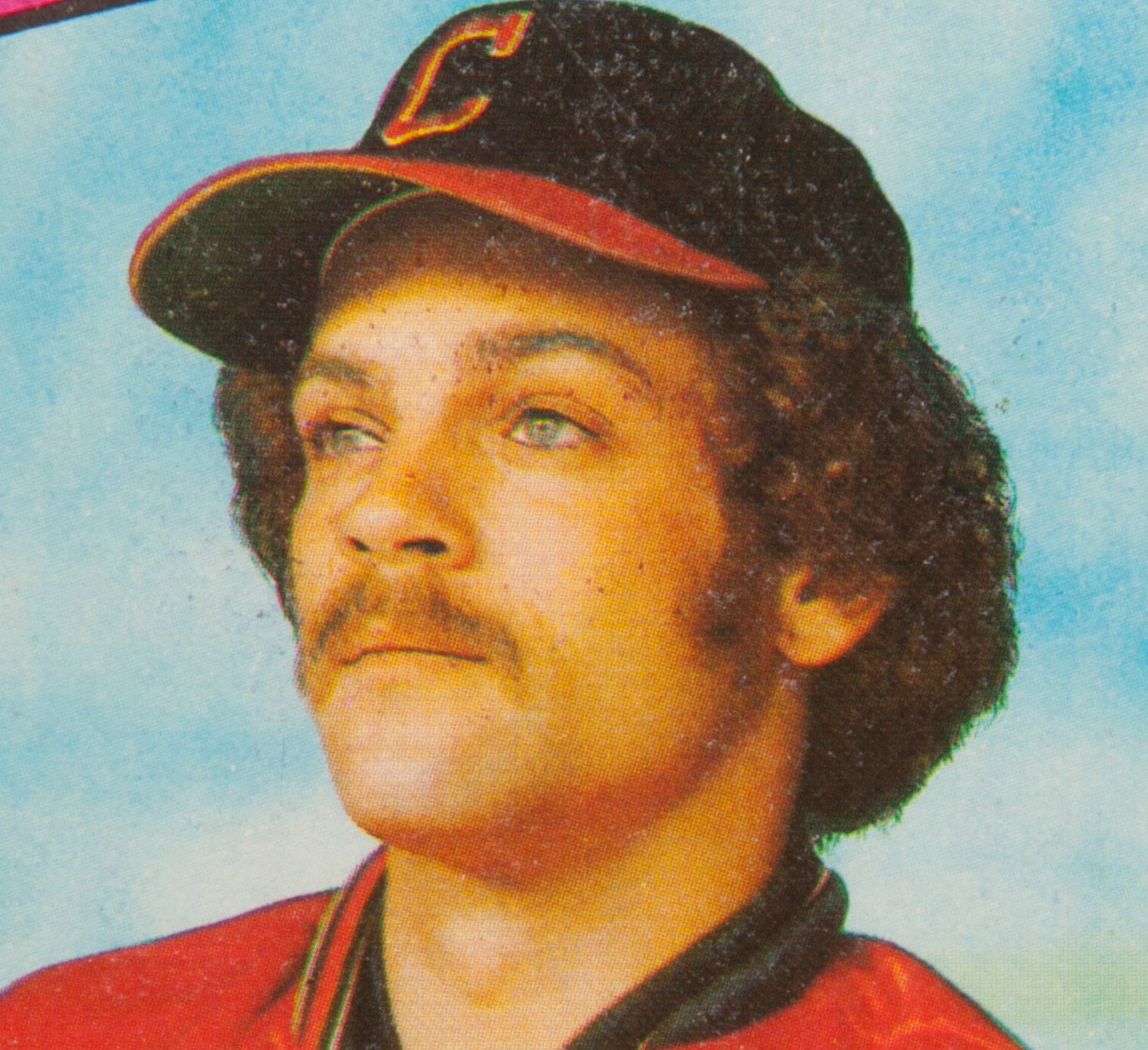

The Royals immediately made Mayberry their starting first baseman. He hit 25 home runs and slugged .507 in 1972, numbers that helped him finish 12th in the American League MVP race. Mayberry and Amos Otis (another trade acquisition) teamed up to provide the main sources of power for the up-and-coming Royals. When the Royals added the Hall of Fame bat of George Brett, the speed and defense of Willie Wilson and Frank White, and the toughness of Hal McRae to the core of Mayberry/ Otis, the 1969 expansion franchise came together to win the first of three consecutive AL West titles in 1976.

During his halcyon days in Kansas City from 1972 to 1975, Mayberry put up power numbers that equaled the best of any left-handed slugger in the American League, with the possible exception of a fellow named Reggie Jackson. In those four seasons, Mayberry crushed 107 home runs, despite having to play half of his games in cavernous Royals Stadium, a boneyard for home runs. Now well known as “Big John,” Mayberry twice compiled slugging percentages of .500 or better, and twice surpassed the .400 mark in on-base percentage. The owner of a sharp batting eye, he drew 122 walks in 1973, and another 119 free passes in 1975. He also reached 100 RBI in three of four seasons.

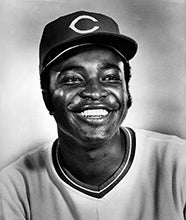

Now let’s look at Jackson. During that four-year window, Reggie hit 122 home runs, while playing in a slightly easier park for home runs in Oakland. He achieved slugging percentages of .500 or better in each of the four seasons, while contributing mightily to a dynastic run of three straight world championships.

Jackson was better than Mayberry, especially if we consider his ability to steal bases and make cannon-like throws from right field. Yet, Mayberry was close, closer than most fans might think at first glance. In spite of the similarity in numbers between him and a Hall of Famer, Mayberry remains underrated.

One of the reasons for that has to do with Mayberry and the fact that he lacked the staying power of “Mr. October.” Beginning in 1976, Big John’s game started to fall off badly. He then had problems during the 1977 American League Championship Series, which the Royals lost to the New York Yankees. Mayberry showed up late to the ballpark for Game 4, and dropped an easy pop-up during the game, allowing the Yankees to continue a rally. Mayberry’s lateness and lackluster play infuriated his manager, Whitey Herzog, who pulled his first baseman after only four innings. Herzog then benched Mayberry for the fifth and final game of the series.

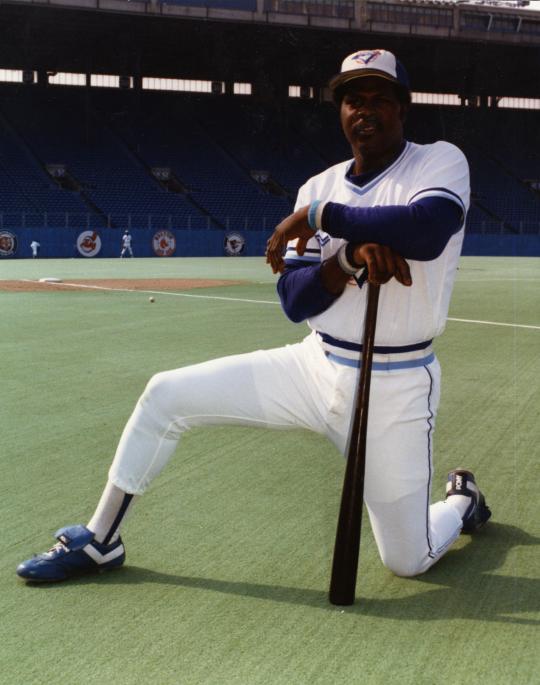

In the spring of 1978, the Royals sold Mayberry to the Toronto Blue Jays in a cash deal. But Mayberry revived his career path north of the border, compiling OPS numbers of better than .800 in three consecutive seasons for the Jays.

A poor start for Mayberry at the beginning of the 1982 season, coupled with the struggling fortunes of the Yankees, would bring the two parties together. With the Yankees thankfully abandoning their disappointing run-and-stun offense that had been headlined by Dave Collins and the elder Ken Griffey, George Steinbrenner decided to remake the team in midseason -- a common occurrence in the 1980s. The Boss began to target potential trade candidates. At the same time, the Blue Jays furiously shopped Mayberry, whom they believed was declining at the age of 33. Much to the delight of the Jays, the Yankees put together a fairly hefty package for Mayberry: Top prospects Jeff Reynolds and Tom Dodd and veteran first baseman Dave Revering.

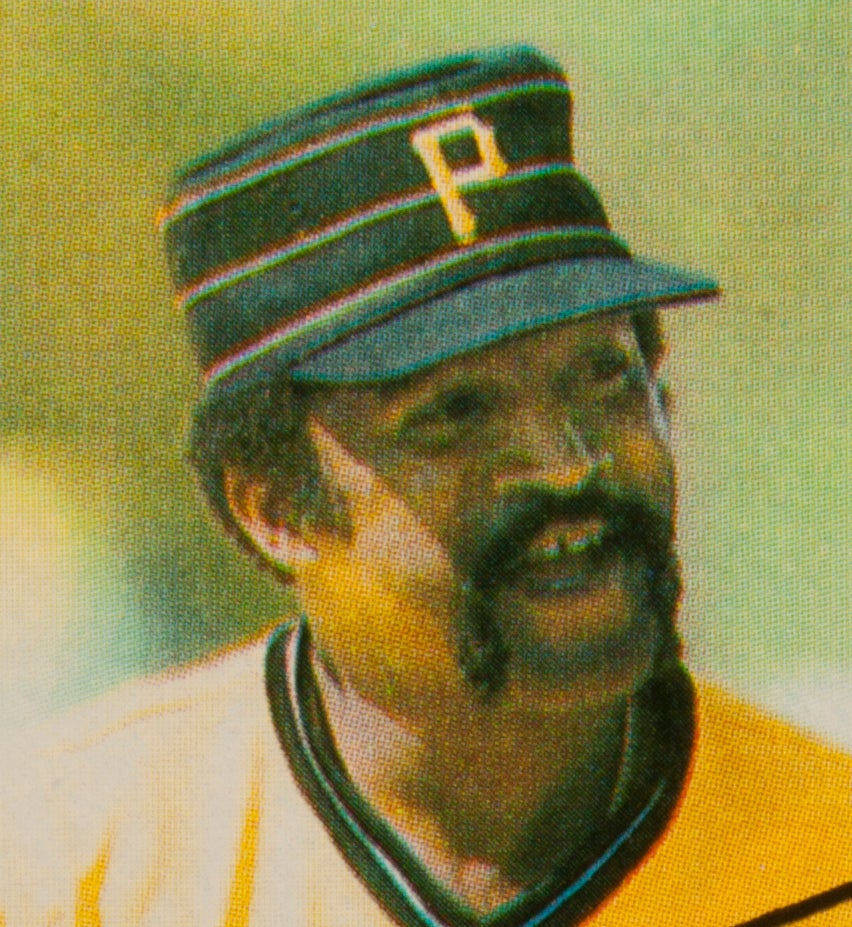

The move marked the end of the “Bronx Burners." And more importantly, it brought the Yankees the kind of player their fans have always loved in the Bronx -- the left-handed slugger. I enjoyed watching the super-sized Mayberry stand at the plate, striking the kind of intimidating pose that only Willie Stargell could match with his similarly imposing frame. If the Yankees could no longer have Reggie Jackson, they could at least have Big John Mayberry.

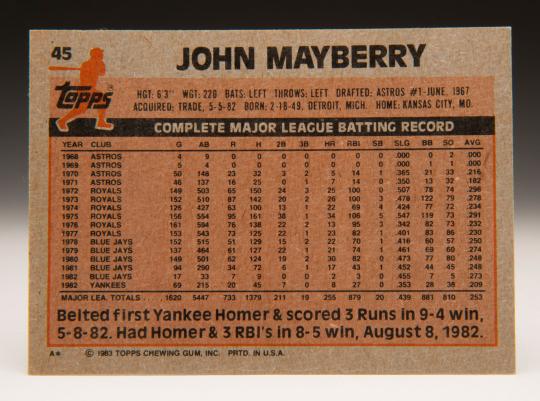

Unfortunately, the trade occurred about a decade too late to benefit the Yankees. Weighed down by a slowing bat, Mayberry couldn’t crank up the power anywhere near his levels in Kansas City, or even those he had established in Toronto. In 215 Yankee at-bats, Mayberry lofted only eight home runs, leaving him with a slugging percentage of .353, his worst in six years. The power-deprived Yankees, who needed a lot more help than Big John could provide, finished four games under .500 and miles behind the division-winning Milwaukee Brewers of manager Harvey Kuenn. About the only consolation that came from the Mayberry trade was the failure of any of the three ex-Yankees to do much of anything in Toronto..

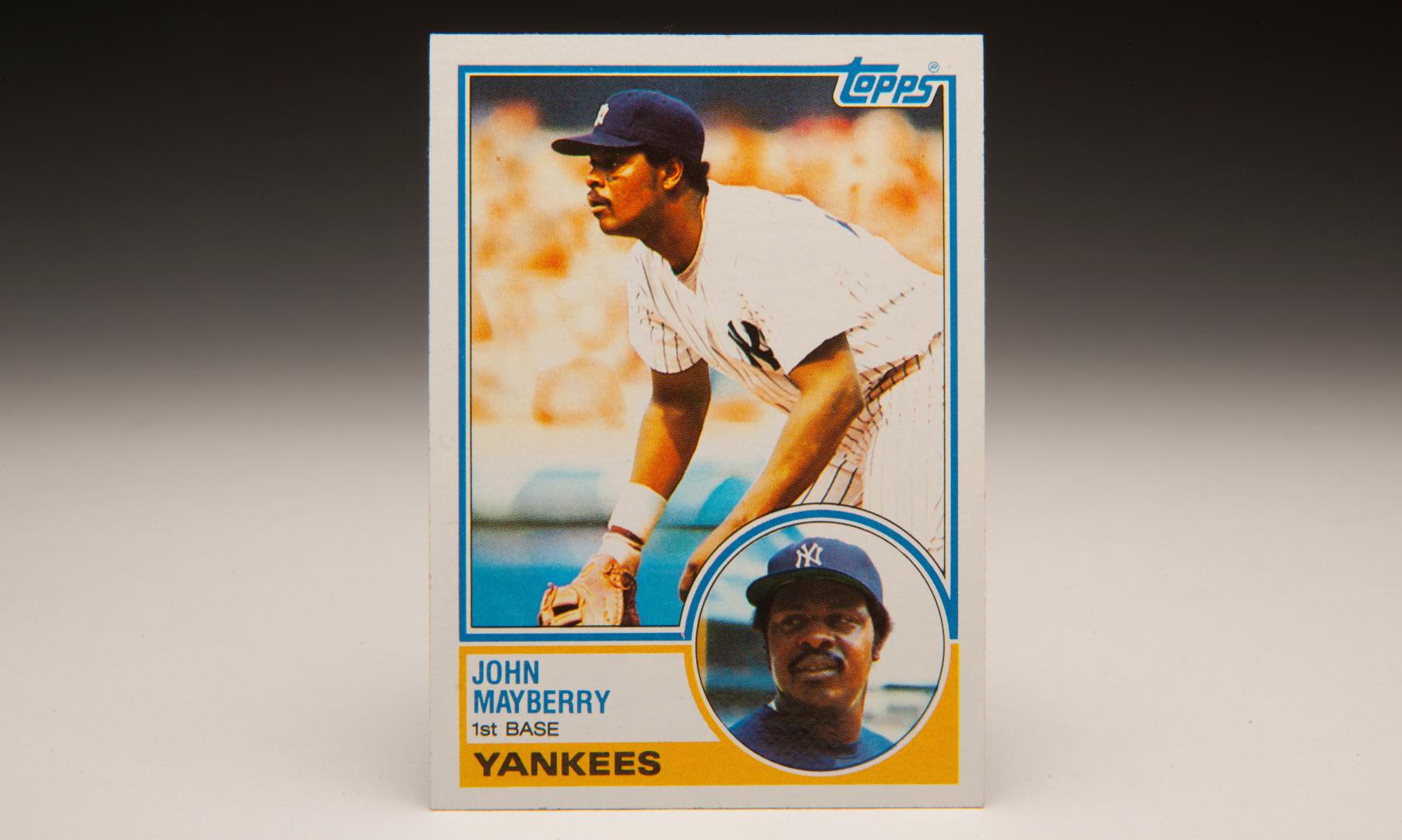

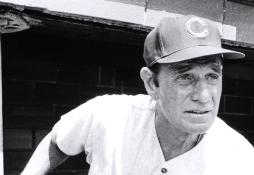

In the spring of 1983, my father bought me a complete set of the newest Topps cards, which included this nifty action shot of Mayberry wearing Yankee pinstripes. It is classic Topps, showing Mayberry taking his crouched position at first base in a 1982 game at Yankee Stadium. The familiar blue padding of the right field wall is in full evidence, as is a blurry crowd in the right field bleachers. As with most players, Mayberry looks good wearing the Yankee pinstripes, which have a slimming effect on an aging slugger. You could put those pinstripes on just about any player, and the effect would be the same: A seeming reduction of about five years in age.

I liked this action shot amidst the backdrop of Yankee Stadium, but the card would soon become a novelty item. During the latter days of Spring Training, the Yankees came to the same conclusion the Jays had determined the previous summer. With a growing supply of first basemen and designated hitters, the Yankees gave Mayberry his unconditional release.

Shortly thereafter, when no teams came calling, Mayberry decided to retire, making his 1983 Topps card the final one issued during his career. As with many former players, Mayberry fell into obscurity, surfacing only briefly as a coach with the Royals and in the minor leagues.

As far as I know, Mayberry had never returned to Yankee Stadium since his retirement, certainly not for any Old-Timers’ games or to throw out any ceremonial first pitches. That all changed in 2009, when Mayberry made it back to the Stadium, not to watch the home team, but to watch his talented son begin his own major league career with the Phillies. As a bonus, he saw junior hit his first major league home run.

Thanks to his son, who is currently attempting a comeback with the Chicago White Sox, Mayberry is a bit better known these days. That’s only right, given how disciplined and dangerous he was in the batter’s box during those prime years with the Royals and the Blue Jays. The next time Mayberry shows up at Yankee Stadium, the broadcasters should know which man is the real Big John.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame