- Home

- Our Stories

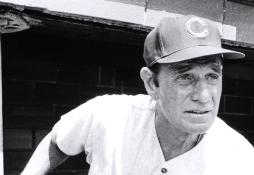

- Bobby Doerr reflects on a life in baseball

Bobby Doerr reflects on a life in baseball

He was, as his friend Ted Williams often said, the “Silent Captain” of the Red Sox – a gentleman off the field and a slugging second baseman on it.

Bobby Doerr’s first big league game came on April 20, 1937, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was President of the United States and World War II was not even on the horizon. By the time he finished his 14-year big league career, Robert Pershing Doerr – named after World War I general John J. Pershing – had established himself as one of the best all-around second basemen in the game’s history.

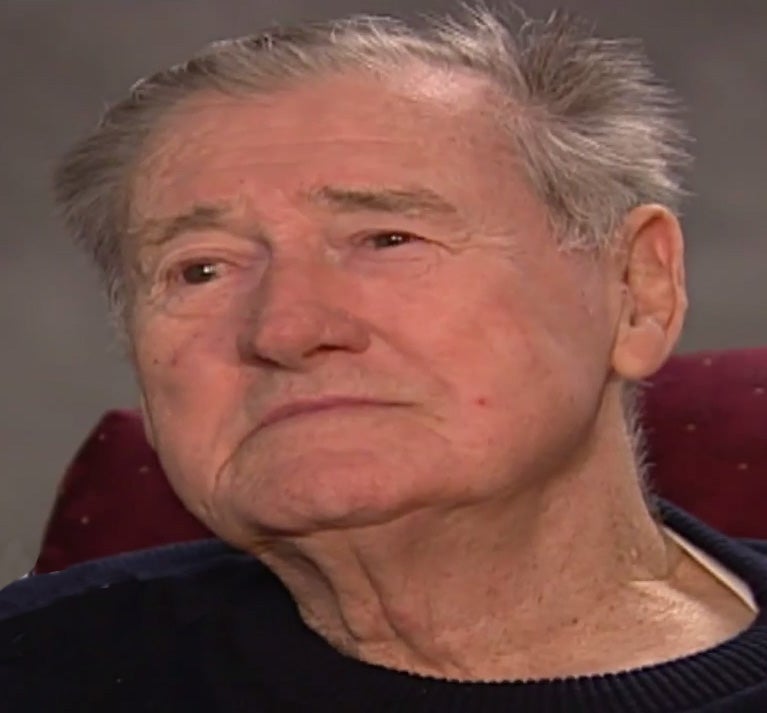

In 2012, Doerr a sat down with then-Hall of Fame Vice President and Communications and Education Brad Horn to discuss his career, his family and a nine-decade life in baseball.

HOF: Growing up in Los Angeles, you were taught the influence of baseball from your dad, Harold, who worked for the telephone company.

BD: He played some baseball when he was younger. He told me as a young boy, if you want to play baseball, I’ll cut the grass and be sure we get to all the practices. He made sure that I was taking care of me, as far as I had to be, in order to play baseball. He had a great great bearing on my life and baseball. He was a wonderful man.

HOF: What other lessons did your dad teach you?

BD: I think he taught me to be like a gentleman, not to be wild, and not to be getting in to trouble. He used to make sure we got the practice in, and not just games. He said that’s when you’ll get good just a lot of practice.

HOF: It was while you were with the Leonard Wood Post team of the American Legion in 1934 that you were signed by George Stovall to your first professional contract, while you were in high school.

BD:I thought it was pretty nice that I had that chance. When I told my Dad that I was going to be signed, he said, ‘Well, you’ve got to promise me you’ll finish and graduate from high school and get your diploma.’ That was one condition that he made in order for me to quit school and go play professional ball.

HOF: The entire Doerr family played baseball.

BD: My brother, Hal, he was a catcher. And he caught for several of the teams on the Pacific Coast teams, Portland and Hollywood. He just wasn’t quite a good enough hitter to go to the majors.

HOF: And your sister, Dorothy played too.

BD: Dorothy played baseball. There was a real top girls team out there. They beat them all. She would have been a great baseball player if she’d been a boy. She have been a major leaguer.

HOF: It was said that you had a natural instinct at second base, even as young player. Did baseball come naturally to you?

BD: Yes, I think so. Ever since I can remember, being 7-8-9 years old, I had a rubber ball that I threw against the first steps of the front porch, and I’d do that by the hour. By yourself you can throw a ball off to the left and you’d have to move your left and field it. I kind of played games, you know, like throw a ball up on the roof and catch it off for a fly ball. I was always either bouncing a ball off of the steps or throwing a ball upon the roof, or catching fly balls off the roof. Once in a while you’d try to throw the ball over the roof and run around and try to catch it on the other side if you were that quick.

HOF: So in 1935, Eddie Collins was general manager of the Boston Red Sox, and you had a chance to meet him while playing for Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League.

BD: Well, that was something, that Eddie Collins came out to see me. He went back to the owner of the club in San Diego and said the Red Sox would like to buy my contract. They said they wanted to see me play another year before they brought me to Boston, though. They shook hands on it, and the Red Sox had the first chance to buy my contract. They did for the 1937 season.

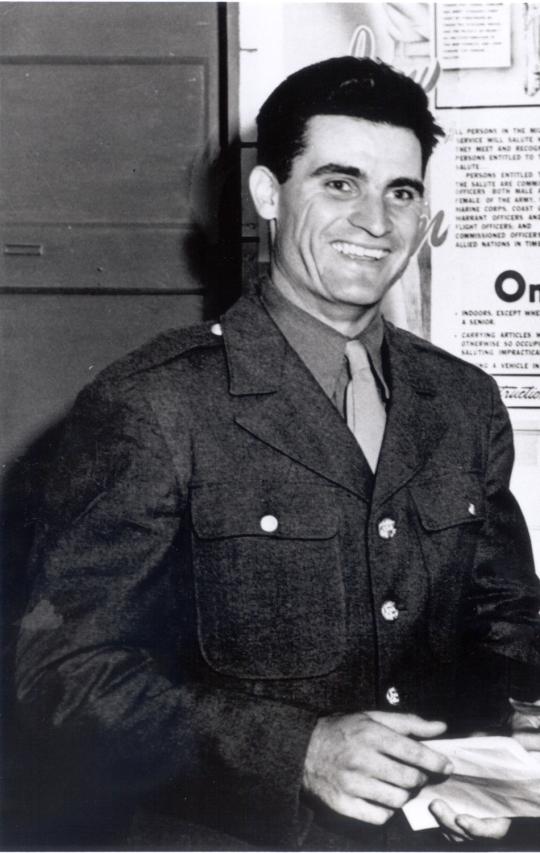

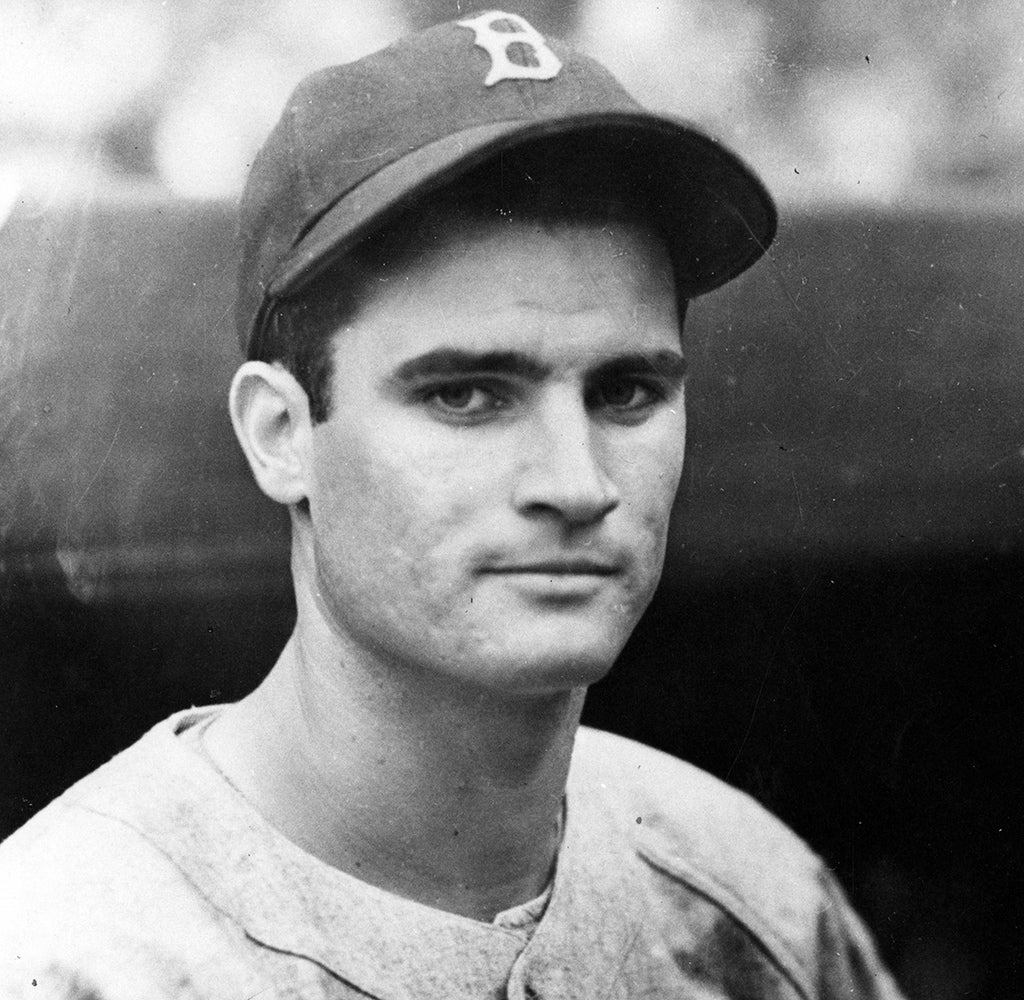

Bobby Doerr served in World War II in 1945, missing the entirety of the baseball season. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

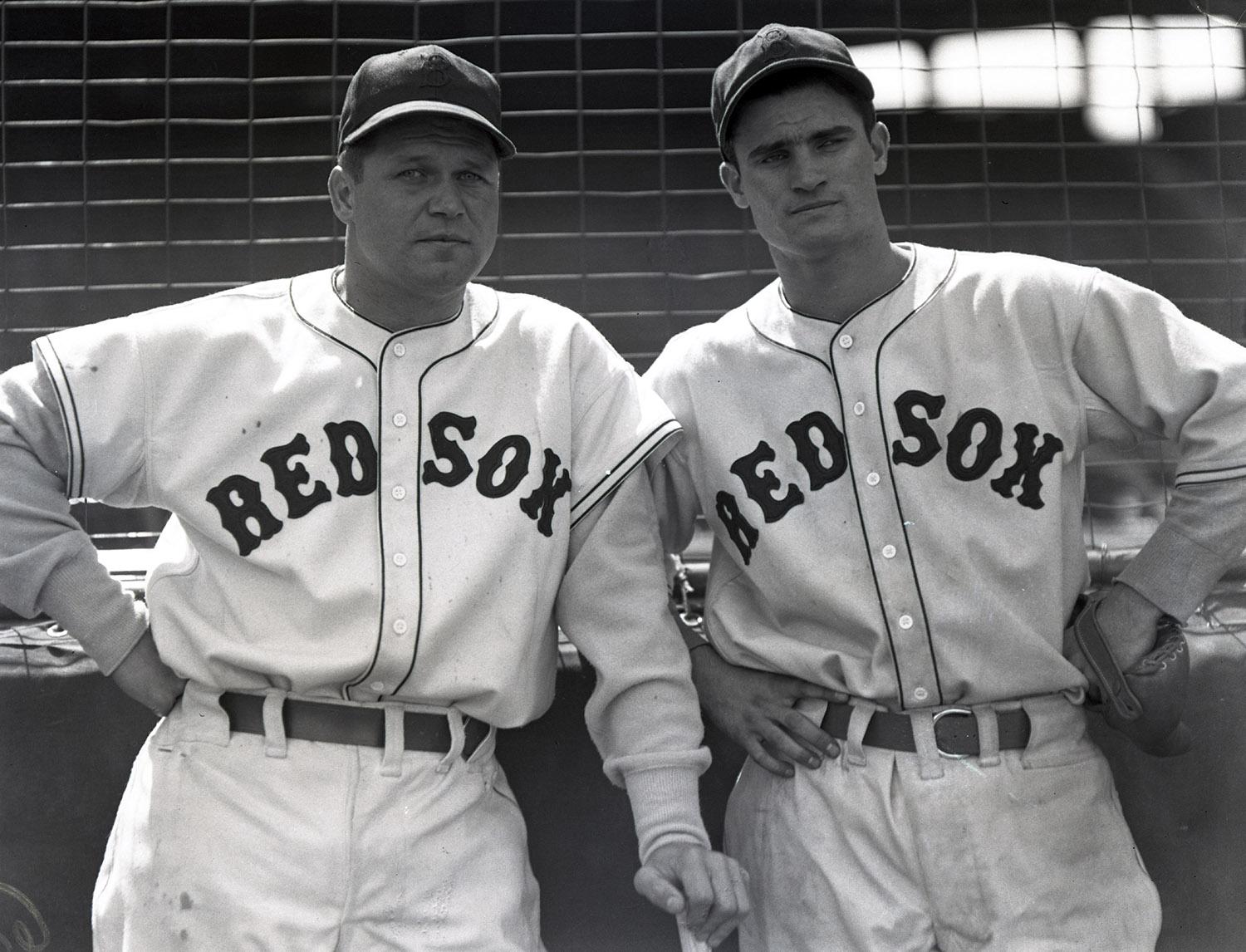

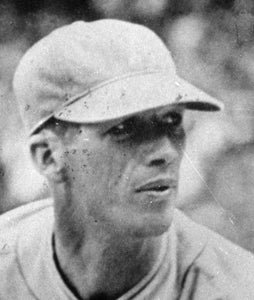

When Bobby Doerr was playing in the Pacific Coast League, Eddie Collins was the general manager of the Boston Red Sox. He came to see Doerr play and told him they'd like to buy his contract. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

HOF: When you knew you were headed to Fenway for the 1937 season, what were you thinking at that point?

BD: Well, I think it was a great thrill that the Red Sox were going to buy my contract and that I’d be playing Major League Baseball. At the start, I kind of put a lot of pressure on myself over it. I didn’t play a whole lot that first year, but starting in 1938, I went on and played regularly from then on.

HOF: What was the biggest difference that you saw in major league pitching?

BD: The pitchers could get their curve ball over better. Also, everyday, you just saw a better pitcher. Back then, you didn’t have helmets or anything. Pitchers would knock you down. Generally if a person hit a home run ahead of you, you’d get a ball up almost under your chin. That was kind of just an automatic thing. But when I look back, I think it really made me a better hitter. It made me more alert. If it was going to scare you, you weren’t going to be there anyway.

HOF: You first made this place here in Junction City, Oregon your home prior to making it to the big leagues in 1937. You bought about 160 acres in 1936, just up the road, that has served as your homestead for your entire life. How did you end up in Oregon?

BD: The trainer of the San Diego ball club, Les Cook, had all these pictures on the wall in the clubhouse, of the fishing and the hunting in Oregon. In between batting practice, I’d always go in to sit with Les. I remember in 1936, I was talking to him about the hunting and the fishing up here, so one day, he said, ‘Why don’t you come up to Oregon with my wife and me this fall and spend the winter.’ Boy, oh boy, I thought that was the greatest. So I did, I went up with them to spend that winter. I spent all winter fishing and hunting. It was really a great part of my life.

HOF: While you were in Oregon, you met your wife, the lovely Monica, and you were married in 1938.

BD: Les talked to me about all the things you could do up there in Oregon, so I could hardly wait to get there and spend the winter. It was there that winter that I met my wife, who was teaching school up there. I didn’t realize she was going to be my wife at that time, of course. But this one night, each Saturday night down the river from us at the C.C. camp, while the boys were building a road over the mountain, they would have a dance one night and have a movie another night.

We would get in the back of this truck, as they’d come pick us up to take us down to the dancing. One night, the people across the river, friends, invited us to come over to their place. It was just kind of dancing from a phonograph. I can remember when we got ready to leave to go back across the river about 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning, Monica was ahead of me in this little old rowboat. The fellow was going to row us across. The seat next to her was all white from being cold and frosty. I remember when I got in, Monica, who would turn out to be my wife, put her coat down so I didn’t have to sit in that old icy seat. And at the time I thought that was pretty nice. I fell in love with Monica that night.

HOF: Then for the 1939 season, you had a new member join your Red Sox lineup – Ted Williams. How did you interact with Ted at the start?

BD: We became pretty close friends, because we were the same age. The San Diego teams we played on had a bunch of older players. So anytime there was a western movie on, why Ted would call me and say, ‘There’s a western movie on with Hoot Gibson,’ or a cowboy movie, so we’d end up going to the movie. We became pretty close friends. It seems like it stayed that way throughout our life in baseball and beyond. Ted was always good with me. He was patient. And I always admired Ted as a human being. He was really a fine person.

HOF: With five future Hall of Famers on that 1939 roster – Joe Cronin, Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Grove, Ted and yourself – did you get the sense, even at an early age, that your team boasted such great talent?

BD: No. I don’t think we ever let ourselves think we were good. You wanted to be a good as you could be, and I don’t think we ever got to the point, ‘I’m good, so I can do whatever I want.’

HOF: What stood out about the 1941 season, as Ted hit .406 and how the team looked at his chase for .400?

BD: As a player, you really didn’t think that much about it. You know Ted was up over that 400 mark. You just were pulling for him all the time. He never thought that much about it. Back then it wasn’t that big a deal, like it is today. Now, it would be constant attention, more and more, would he hit .400? Everybody was always pulling for Ted. He was a likable guy. We were happy when he ended up with 406. That was quite a feat.

HOF: You and Monica would have to travel the length of the country every year, to get to spring training and then to the regular season in Boston.

BD: We’d start out before spring training, go visit my folks in Los Angeles for a couple of weeks, and then we’d drive a cross the country to Spring Training in Sarasota. Then we’d get somebody to drive our car up to Boston. It just seemed like that was the routine, and then in the fall, we pack up the car and head home for the winter. It was pretty nice to be able to come back out to Oregon and go fishing and hunting and have the life I had.

HOF: In 1943, you really had a nice year and had a very special moment in the All-Star Game, a 3-run home run off Mort Cooper to set the American League on the road to victory.

I can still remember that pitch. It was a hanging curve ball that I fell back on. It just seemed that it wasn’t a real hard pitch to hit, and it was one of the real great thrills I’ve had in baseball.

HOF: The 1946 season turned out to very special for the Red Sox. Though you lost the World Series in seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals, you led Boston with a .409 batting average, the surprise offensive star for the club.

BD: That was kind of interesting. Towards the end of that year, we took the pennant quite early the first part of September and I can remember that I’d go out for hitting, and I was in a little bit of a slump that first part of September. Then, toward the last part of that month, as we got closer to the Series, I kind of came out of it. I changed bats and went with a lighter bat. I kind of choked up on the bat a little, and then I got to hitting pretty good.

HOF: If not for you, Bob Feller might have easily had five no-hitters instead of three. You had the only hit for the Red Sox in two of his 12 one-hitters.

BD: In 1939, it was a cold, cold day. And Bob had so much stuff that day. He had more stuff that day than anytime I saw him. He had to be throwing close to 100 miles an hour. I broke my bat, and hit a little bloop over second base for a base hit to break up the no-hitter. And then in 1946, I hit a line drive over the shortstop. He was tough. He had a big arm and pitched with emotion. He didn’t try to knock you down. I’m sure he never, at any time, just threw at you - just once in a while because of that big-guy emotion. The ball might get away from him, and it might end up behind you or what not. You didn’t go up there with a real rigid stance against him. You were a little loose at the plate when he pitched.

HOF: You were an extremely good hitter in the clutch. In fact, your six walk-off home runs still are third-most in Red Sox history.

BD: Is that right? I didn’t realize that. I remember sometimes we’d be one run behind or something like that, and I’d hit a homerun that either tied it or won it. What did you say it was, six times? I didn’t realize that. I’ll be darned.

HOF: In 1951, you retired in September, your back was just bothering you too bad.

BD: I remember a cold night in Cleveland about two weeks before then that I went down quick to get a double play ball, and I felt something kind of give in my back. I went out of the line up, and I was out for about two weeks when I came back. I thought I was good enough to play then, but I remember the first time I swung, it felt like someone was sticking a knife in my back. So that was time, I had to retire.

HOF: You were just 31, could you have come back to play?

BD: No. I doubt it. They said I would have had to have a disc fused in my back, and I just don’t think I would have been able to come back.

HOF: What was it like playing for owner Tom Yawkey and in being a member of the Red Sox family?

BD: Oh, he was a wonderful man. He treated his players well some might even say maybe he treated them too good. We just never had the consistent pitching but that one year in 1946 when we won the pennant. Boo Ferriss and Tex Hughson had the big years and then they both got store arms the next year, so we had to come back and develop new pitchers, guys like Mel Parnell. But our key pitchers never came back strong.

HOF: In 2012, the baseball world will celebrate the 100th anniversary of Fenway Park. Can you believe how it has been renovated to stay so fan-friendly.

BD: Well, it’s been kept up nice. It has that unique close left field fence, but you still have to hit a ball good to hit it out of the ballpark. Sometimes the winds are blowing awfully high and a high fly ball will go out when it wouldn’t go out of other ballparks. I remember when I first went to Boston, in spring training, in ’37, (manager Joe) Cronin took me through his office, back up on third base in the top of the stands, and he said, ‘Bobby, this is where you’re going to be playing.’ And I’ll never forget the sight of seeing Fenway Park for the first time. Looking at that short left-field fence, it was a beautiful park to see. It was well-done then, and they’re doing real good to keep it up like they are today.

HOF: As fans enter Fenway Park, they look on the right field façade and see a series of retired numbers, starting with Bobby Doerr’s number 1.

BD: That’s a great thrill, to think you’ve got your number up there like that. I just marvel at having it up there. It’s great.

HOF: How did the fans treat you at Fenway Park?

BD: They were really good to me, all the time. Lolly Hopkins sat in back of first base and she’d come to the ballpark every day. I think she had to come something like 60 miles to come to the ballgame. As soon as I came out of the dugout she’d say, “There’s my Bobby”.

The fans are what it’s all about, and I think they do a very good job at Fenway Park to keep it up nice and treat the fans like they do. To think that every day is a sellout, you have to give the management a lot of credit for keeping things up like that.

Those fans are tremendous. You hustle and play, and even if you don’t do well, as long as you feel like you’ve hustled, they’ll stay with you. I think they’re the greatest fans I’ve seen.

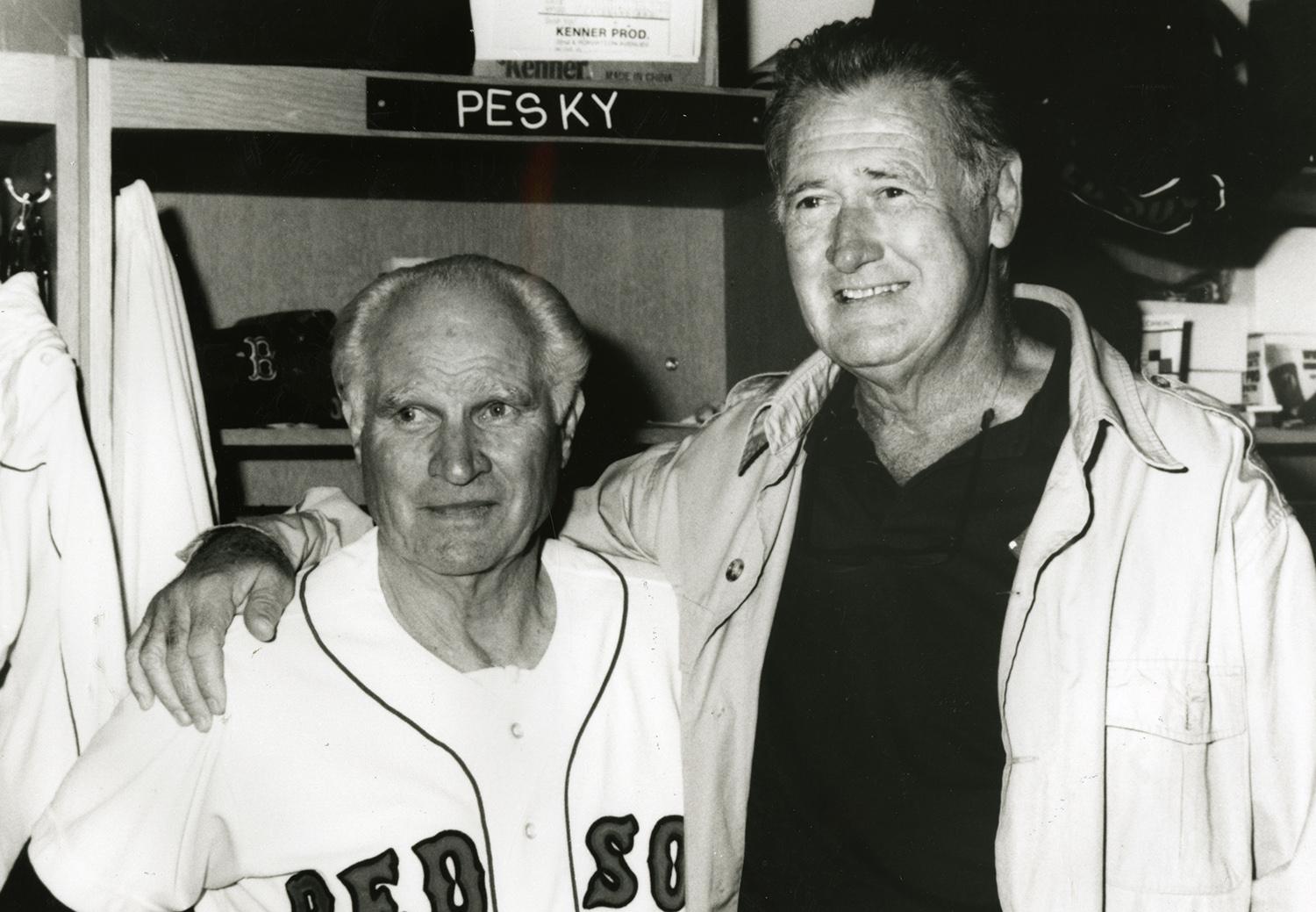

HOF: Much was written in the book “Teammates” about the friendship you, Dom DiMaggio, Johnny Pesky and Ted Williams shared throughout your life, on and off the field. What do those friendships mean to you?

BD: Well I guess we were all from the Pacific Coast, and we kind of grew up together, in a way. Everybody pulled for each other. It was lucky that we finally all got to stay together during that period of time.

HOF: So you had Fenway Park in the summer and Oregon and the Rogue River in the fall and winter. What was the better home-field advantage?

BD: Fenway Park was so wonderful to be able to play baseball there. It definitely was my home. I felt fortunate that I could play there, then, that I could play in that beautiful ballpark, and then just to think that I could come back out here to Oregon and go fishing and hunting and have the privacy you had there. I was just very lucky to have both of them, I guess you’d say.

HOF: Were you a better ballplayer or fisherman?

BD: The ballplayer in me would have to get the nod. I spent more time playing baseball and trying to be good at that. Fishing was just a good relaxation. I wasn’t what you call a great fisherman, I fly fished pretty good. Fishing was a good relaxation, and I would do it as much as I could during the wintertime.

HOF: And here in Oregon, there’s some pretty good fishing. Particularly the Rogue River.

BD: To have a home on the Rogue River was great and the Illinois River ran in just down below, into the Rogue, so you had two really good fishing streams. The Illinois always ran pretty clear, whereas the Rogue, if it ran muddy, you could always go fish the Illinois. It always had good fish.

HOF: A few of your teammates came out to fish here in Oregon while you were playing.

BD: Birdie Tebbetts came out one time and fished with me and Ted fished a few times out there when I was still playing. Ted always wanted to catch the bigger fish. Out there on the Rogue, you caught what you call half-pounders – 15-16 inch steelhead that were good spicy, fighting fish on the fly, but Ted wanted to catch those 5-6 and 8-10 pounders. He’d go up in New Brunswick, Canada and fish for those up in there. He was always looking for the best all the time. Of course in his position, he always got the best.

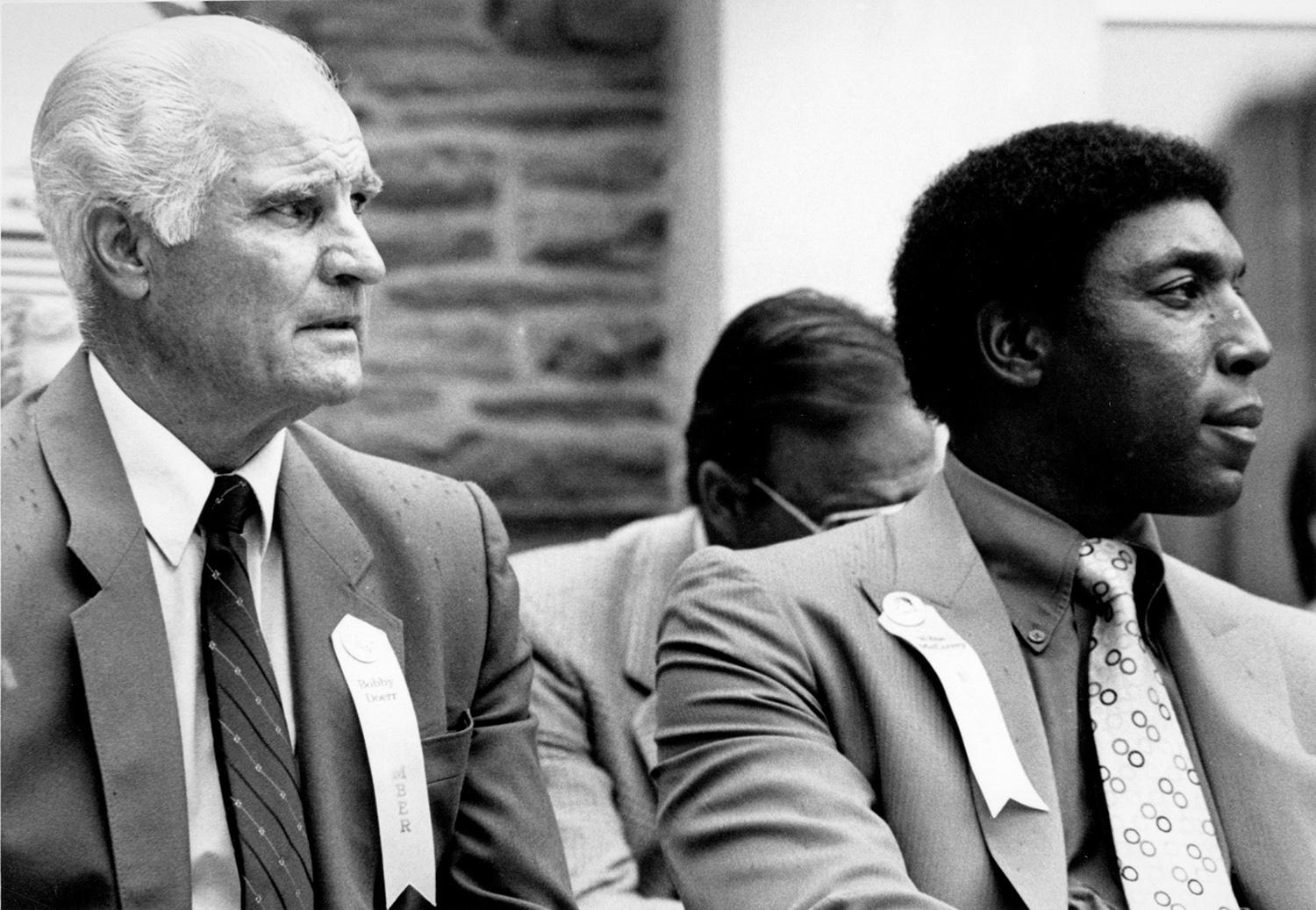

HOF: In 1986, you received a phone call that changed your first name, to “Hall of Famer” Bobby Doerr.

BD: That was always the top of everything, to think that you got into the Hall of Fame. I remember when they called me, Ted Williams was there with Ed Stack, the Museum President. ‘You just made the Hall of Fame,’ Ted said to me. It was really a great thrill, because that is the ultimate of everything in baseball, to think you made the Hall of Fame.

HOF: How you would define what it has meant to you to be a Hall of Fame member?

BD: It meant you can go any place and you get to meet a lot of nice people, and you’re recognized as something good. You don’t have to be an outcast to be recognized. I like to think good guys can finish first. I think you can be a good guy and still be recognized. It’s something to think I could be in baseball all my life. And baseball’s been good to me. I sure could never criticize anything about baseball.

Brad Horn was the vice president, communications and education at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum