- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1991 Topps Oscar Azocar

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Oscar Azocar

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

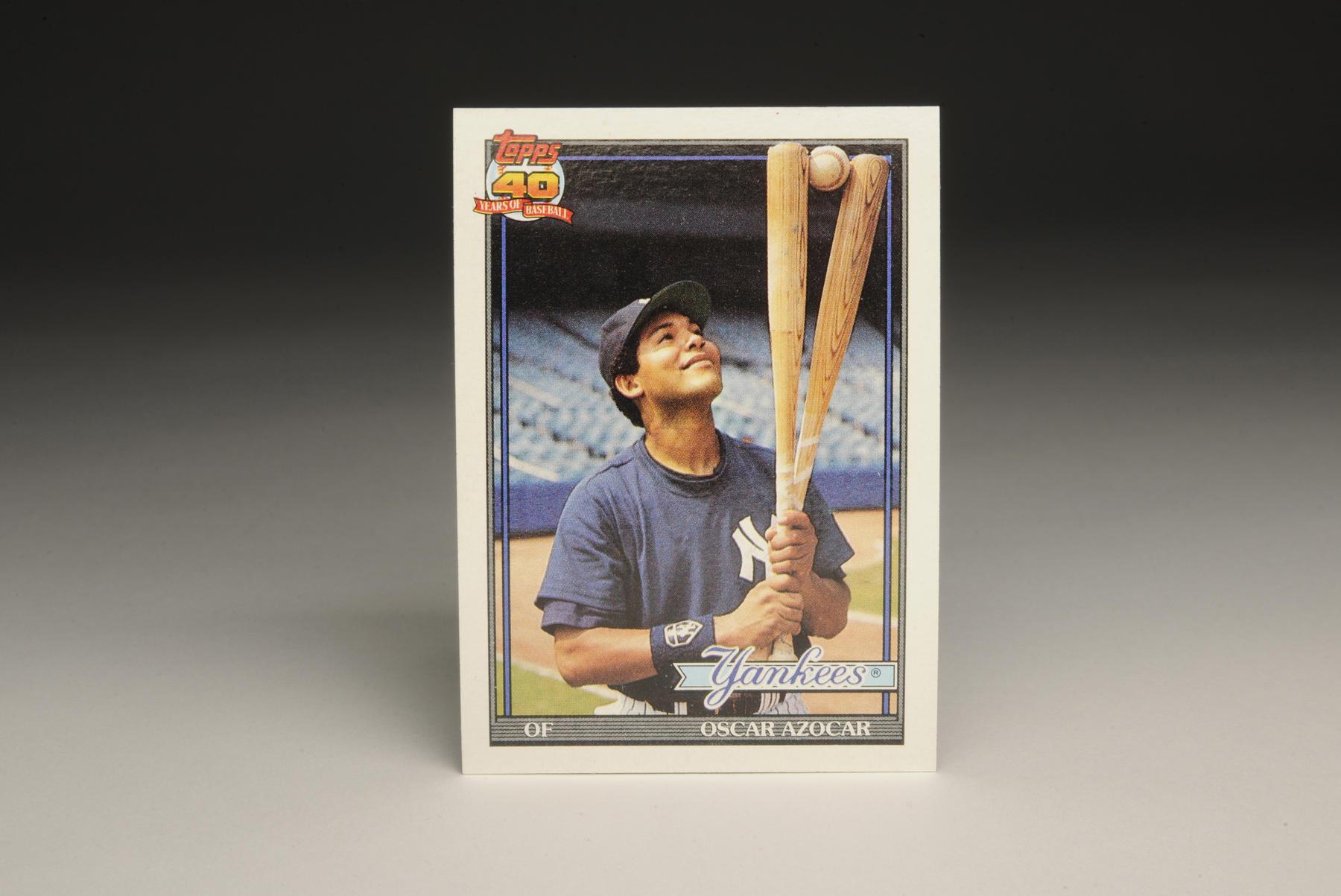

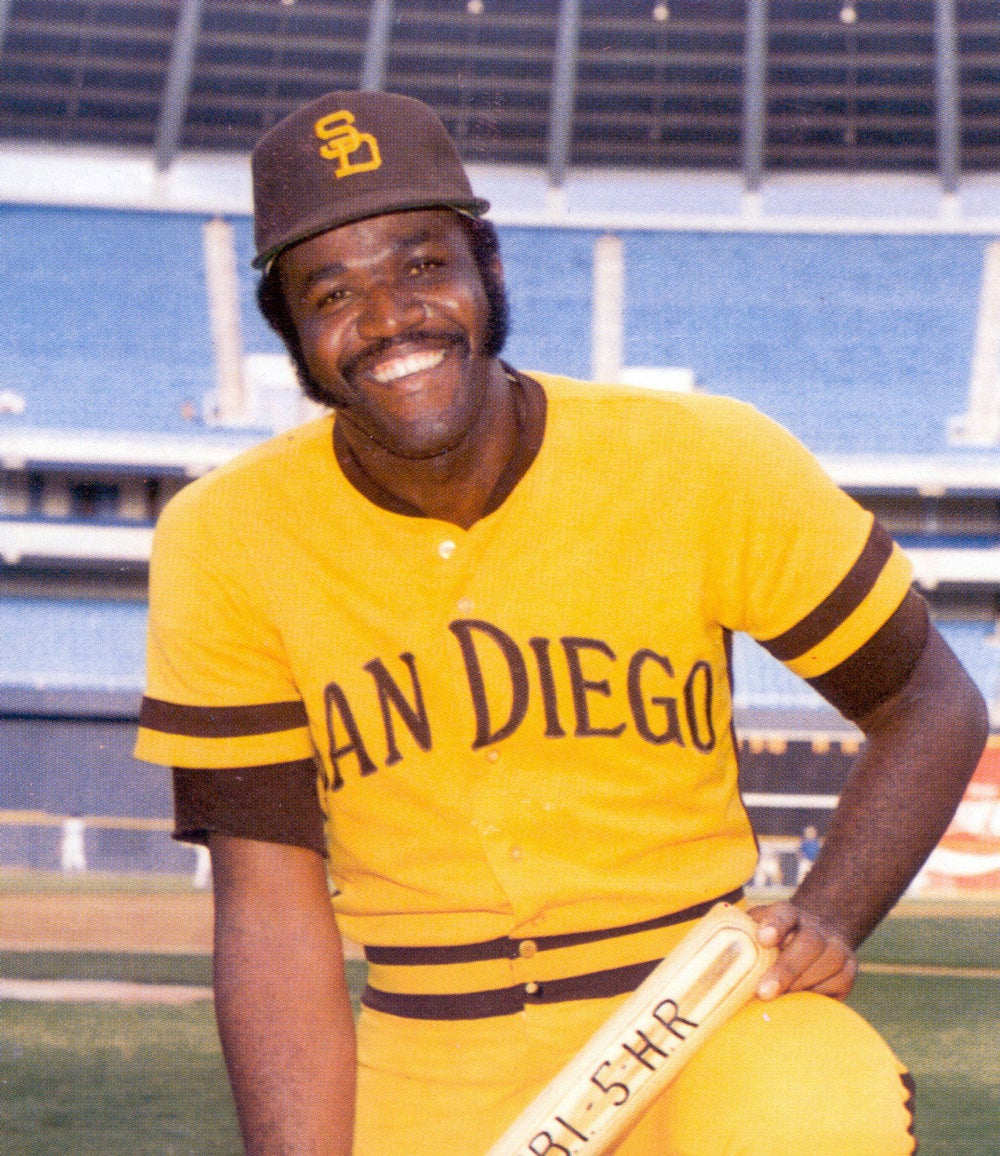

For his 1991 Topps card, a smiling Oscar Azocar decided to do something special. As we see here, he has taken two bats and a baseball, and is opting to have some fun with them. Gripping the bats near the knobs, Azocar holds them extended upward, parallel to each other. He places a baseball between the barrels of the bats, somehow balancing the ball in place while keeping the bats extended. I’ve never seen this done. I’ve never even seen this attempted. I don’t know how hard it is to do this, but it looks like it would take far more coordination than I naturally possess. It might even take more coordination than most major leaguers possess. I do know this: It’s pretty cool.

For too long, I used to think that Oscar Azocar epitomized the struggles of the New York Yankees teams of the early 1990s. A free swinger, Azocar struggled so much in trying to reach first base that many Yankee fans considered him synonymous with the team’s tribulations during that era. I felt especially bad about that in June of 2010, when I learned that Azocar had died suddenly and unexpectedly from a heart attack at the age of 45. I only felt worse when I started to read about Azocar, learning more about a hustling ballplayer, a fun-loving teammate, and a delightful man who played every game as if it were his last.

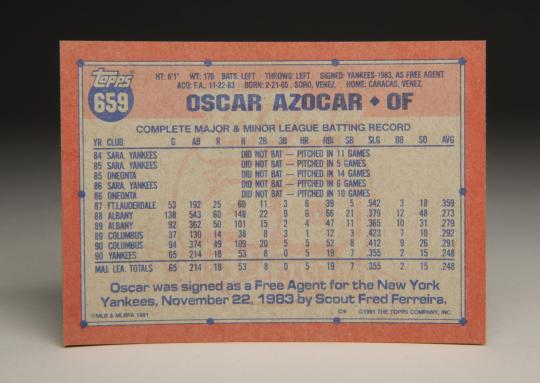

Born and raised in Venezuela, a young Azocar caught the attention of the New York Yankees, who offered him a contract—as a pitcher. Signing him as an 18-year-old in 1983, the Yankees watched him pitch for three seasons. He showed a good screwball and curveball, but didn’t throw hard enough to advance past A-ball.

In 1987, Oscar’s minor league manager, a young Buck Showalter, decided to allow the pitchers on his team to take batting practice once a week. Showalter was so impressed by Azocar in the batting cage that he informed his superiors within the organization. The Yankees soon gave the approval to switch Azocar from the mound to the outfield.

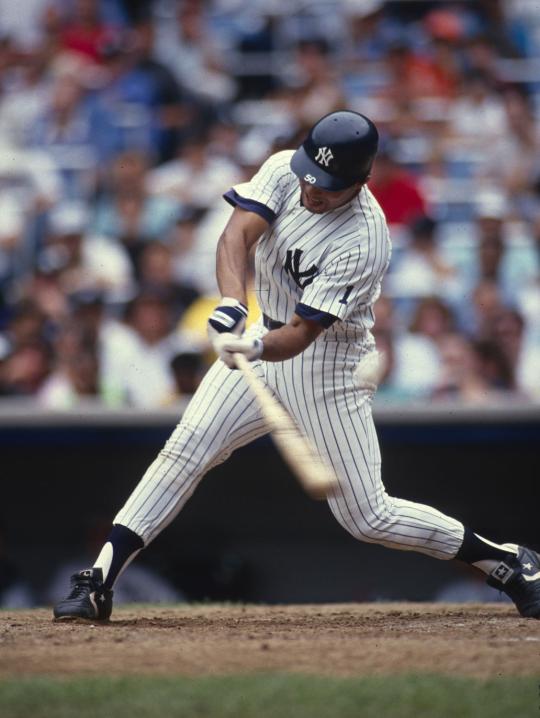

Only three years later, Azocar completed the climb. In July of 1990, the Yankees brought him to the big leagues and watched him deliver a profound first impression. Appearing as a pinch-hitter in his first at-bat, Azocar pounded out a single. In his next game, he singled, doubled, and homered. Through his first 20 games, the rookie outfielder compiled a robust .320 batting average and four home runs.

Azocar’s aggressive style of hitting eventually caught up with him. Over his first 130 plate appearances, he had no walks. He fell into a terrible slump, sinking his average into the .240s. By the time he had finished his rookie season, Azocar had stepped up to the plate 218 times—and drawn the grand sum of two walks. Swinging the bat from a pronounced crouch, he swung at almost any pitch within the general proximity of the batter’s box. In one stretch, he came to bat seven consecutive times without taking a single pitch.

For a while, Azocar had more sacrifice flies than walks, which resulted in the unusual situation of his batting average being temporarily higher than his on-base percentage. At season’s end, his batting average rested at .248 and his on-base percentage at .257.

While it’s true that Azocar didn’t walk and didn’t hit with any tangible power, he did play the game with a level of passion not normally exhibited by most major leaguers. Even on a ground ball pack to the pitcher, Azocar sprinted all-out to first base as if he were playing in the seventh game of the World Series.

When Azocar played left field, he made sure to fully involve himself, even when the ball was not hit in his direction. On a batted ball to another outfielder or infielder, Azocar would make a mad dash toward third base, so that he would be in position to back up his third baseman on a possible overthrow. It didn’t matter if the chances of there being a play at third were tiny; Azocar wanted to be there, just in case. Azocar did something similar when runners from first base attempted to steal second base. If the catcher’s throw happened to trickle into center field, Azocar would back up third base in the event of a second overthrow.

Some of the veteran Yankees noticed Azocar’s habit of running furiously toward third base on these possible overthrows and poked fun at Azocar. A few Yankees asked Azocar why he did this. Looking a bit bewildered, Azocar thought for a moment and then replied in his heavy Venezuelan accent: “Because that’s what I’m supposed to do.” The other players might not have bought into this, but Azocar was right. He didn’t have anything else to do on the play, so he might as well put himself to use—just in case. That’s just good fundamental baseball.

In addition to his perpetual hustle, Azocar exhibited other good habits on defense. He tracked fly balls well and usually hit the cutoff man with his throws. Best utilized as a left fielder, Azocar had enough speed to dabble in center field, at least on a fill-in basis. He could also handle right field, though his arm strength was something less extraordinary than that of Jesse Barfield, who played right field for the Yankees at the time.

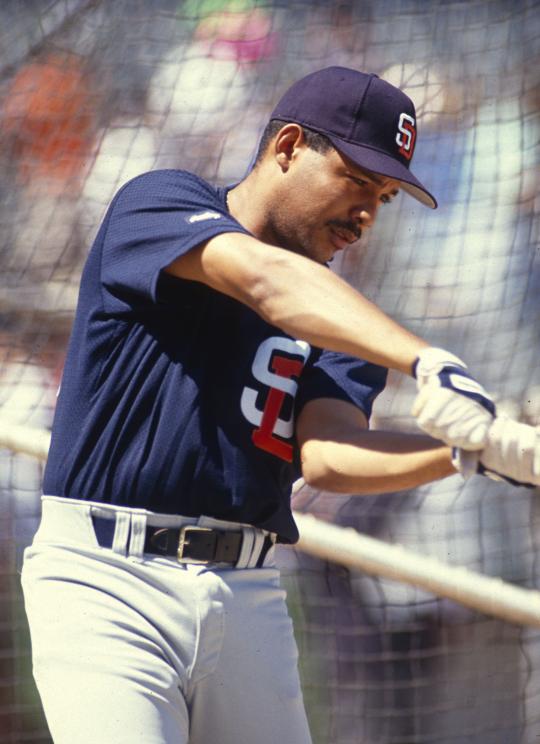

Azocar could run the bases, too. Though hardly a blazer, Azocar knew how to read pitchers and steal bases. Over parts of three major league seasons, including a pair with the San Diego Padres, Azocar stole ten times without being caught, setting an unofficial major league record.

Although Azocar’s major league career lasted only three seasons, he continued his playing days in the Mexican League. There he became a long-term success, playing from 1993 to 2001. On three occasions, he hit .330 or better. Reaching his peak for Oaxaca in 2000, Azocar batted .377 with 15 home runs. He also drew 28 walks while striking out only 16 times.

Still, there was much more to Azocar than pure numbers. He loved to smile. He smiled during games. He smiled, and laughed, in the dugout. He smiled before games. Azocar simply loved playing baseball, along with the experience of being around the ballpark. With his upbeat and enthusiastic approach, Azocar became a wonderful teammate. Azocar just seemed delighted to be hanging around a major league setting, spending time with players ranging from Don Mattingly to Steve “Bye-Bye” Balboni to Hensley “Bam-Bam” Meulens.

Azocar’s pleasantness extended to members of the media, apparently even to the Topps photographers who came by each spring to photograph players for the next set of cards. I imagine that many players don’t give the Topps photogs more than a moment of cooperation. They’ll offer the usual pose, a batter pretending to swing his bat, a pitcher holding his glove in one hand and the ball in the other. But that clichéd kind of pose wasn’t enough for Azocar; he wanted to do something out of the ordinary, like holding a baseball between two bats held up in the air. The creativity, the playfulness, and the joy that Azocar exhibits in this photo make this one of the most charming cards of all-time. Even though it’s probably worth only a few pennies, it’s an absolute classic.

Even if his batting average exceeded his on-base percentage, Oscar Azocar would have made everybody at the ballpark feel better. And there is certainly some value in that.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame