- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert

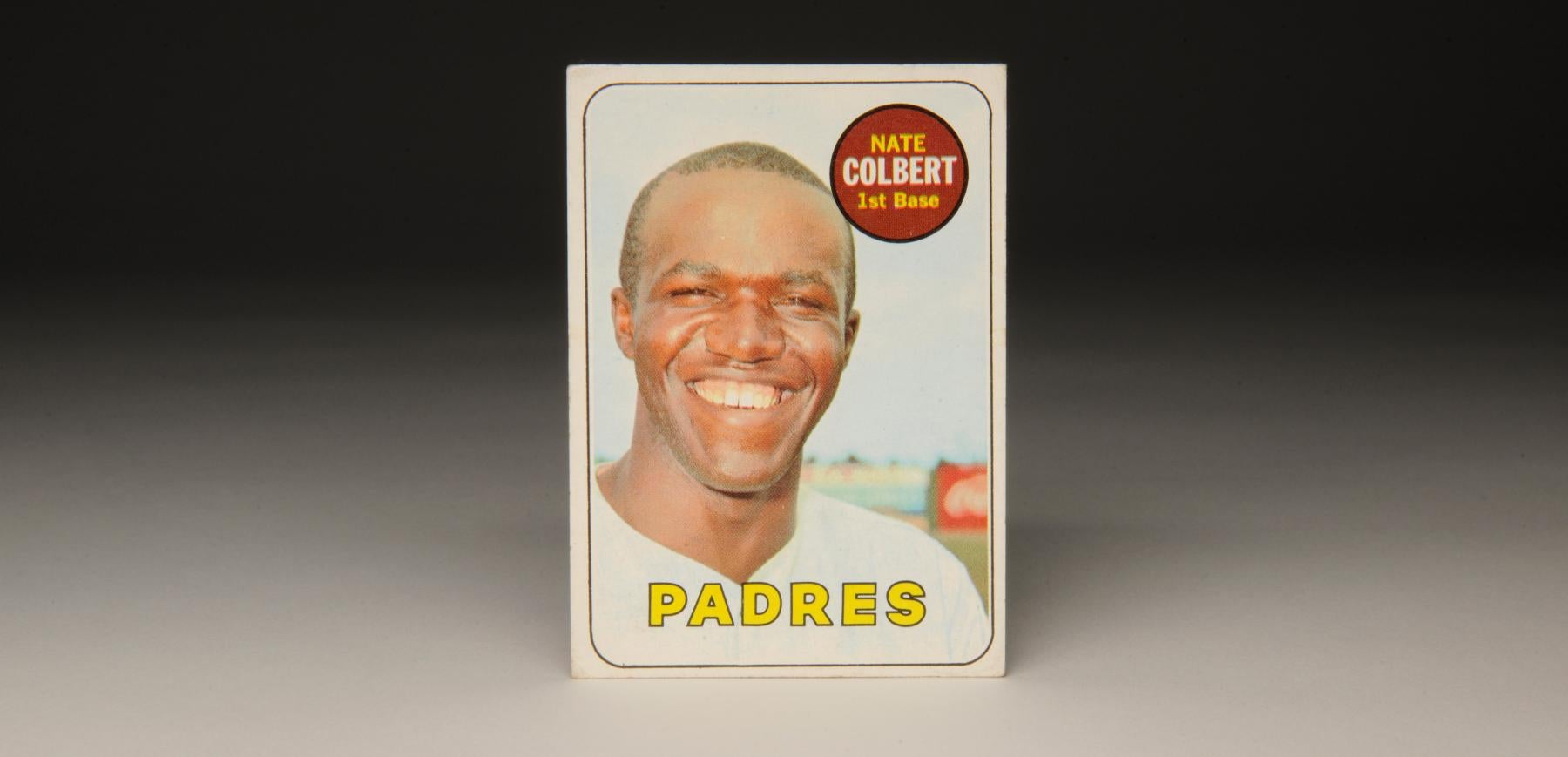

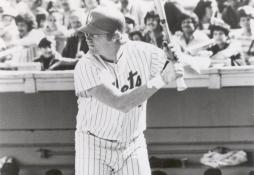

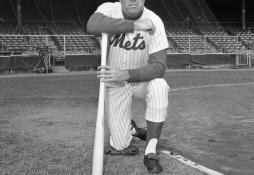

We should not be surprised to see Nate Colbert smiling on his 1969 Topps card. In many ways, that’s just Nate being Nate. In the same way that he appears on his Topps card—smiling so widely to the point of exuberance—Nate Colbert has always looked at the bright side of things. Perhaps this baseball card offers photographic evidence of his happiness over being a major leaguer, fulfilling a dream that he had fostered since childhood.

Although Colbert did not know it at the time this photograph was taken (likely sometime in the spring of 1967), he also had good reason to be positive about the next step of his career. After the 1968 season, Colbert would join the San Diego Padres via the expansion draft. He would soon become their starting first baseman—and the first star in the history of the new franchise.

Aside from his wide smile, there is something else noteworthy about Colbert’s 1969 Topps card. He is not wearing a cap, not for his old team (the Houston Astros) or his new team (the Padres). This was a common technique used by Topps at the time. The company had its photographers take capless photographs of players, in the event that the player changed teams during the season or over the course of the winter. That way, Topps would not be saddled with an outdated photograph of the player. With the capless pose, Topps could easily crop the photo so as to eliminate showing the name or logo of the old team on the jersey. Without the cap, the player became more generic, and less identified with his previous ballclub.

If Colbert had chosen a different path, he might very well have worn the cap and uniform of a more established franchise, the New York Yankees. As an amateur free agent in 1964, the year before the major league draft became a reality, Colbert was pursued hotly by the Yankees. They had promised to double any offers given to him by any of the other 19 major league teams, but Colbert turned them down. He had his heart set on a different plan of action.

It’s always fun to consider what might have been. If the Yankees had signed Colbert, they presumably would have brought him to the majors by the late 1960s. That would have been good timing for the struggling franchise, considering the instability the Yankees had at first base. Mickey Mantle’s retirement announcement in the spring of 1969 had forced the Yankees to switch Joe Pepitone back to first base from the outfield. But Pepitone himself would depart after the 1969 season, via a trade with the Houston Astros. That would leave the Yankees in a first base quagmire over the next several years.

From 1970 to 1974, the Yankees endured a period of instability at the position. Role players like Danny Cater, Johnny Ellis, and Mike Hegan, and the oft-injured Ron Blomberg took turns playing first base, but none with the productivity of Colbert, who was entering his prime. Colbert would have supplied some much-needed right-handed power to the Yankees, balancing a lineup that had Bobby Murcer (and later Graig Nettles) from the left side of the plate.

It was not to be. Colbert briefly considered the Yankees’ offer, but opted to sign with his hometown St. Louis Cardinals. That was Colbert’s dream; he had always wanted to play for the same team as his idol, Stan Musial. Unfortunately, the Cardinals had such depth at first base and in the outfield that Colbert faced major roadblocks for playing time. After the 1965 season, the talent-rich Redbirds left Colbert unprotected in the Rule 5 draft.

The Astros jumped in and picked up Colbert, who had to stay on the major league roster the entire 1966 season. As it turned out, Colbert would cross paths with the Yankees one more time. Prior to the start of the season, the Astros hosted the Yankees in an exhibition game at the Astrodome, giving Colbert his first glimpse at a Yankee legend. “Mickey Mantle was taking batting practice,” Colbert said during a 2007 visit to the Hall of Fame, as he recalled his own boyish enthusiasm upon seeing The Mick. “I said to my teammates, ‘Oh my gosh! Hey guys, that’s Mickey Mantle.’ The other guys on the team just said calmly, ‘I know.’ “

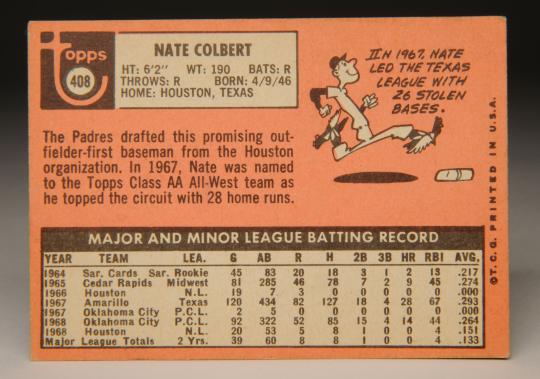

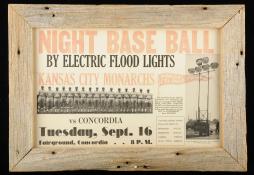

Later that spring, Colbert made his major league debut, continuing the family’s legacy at the game’s highest levels. (Colbert’s father, Nate Sr., had played as a catcher in the Negro Leagues, where he used to catch for Satchel Paige.) But Colbert appeared in only 19 games all season, accumulating only seven at-bats without a hit. It was a slow summer for the 20-year-old slugger.

In 1967, the Astros assigned Colbert to Double-A Amarillo for some needed minor league seasoning. He then returned to the Astros in 1968, but he hardly played, given the presence of Rusty Staub at first base and Bob Watson in left field. When Colbert did receive playing time, he produced poor results, striking out in nearly half of his at-bats.

If there was a consolation to the 1968 season, it was the opportunity to meet up with the most colorful teammate of his career. Colbert remembers well playing with Doug Rader, the offbeat third baseman who was nicknamed the “Red Rooster.” “When we were with the Astros, he and one of the guys, another player on the team, went down to the pet store. That’s when it was legal to own alligators. And they bought three alligators, baby alligators. They waited until we were all in the shower, and they let them loose in the shower, down in Cocoa, Fla. We were trying to climb the walls, these little baby alligators all around us.”

With teammates like Rader, Colbert found fun away from the field. But he longed for an opportunity to do more than merely pinch-hit and fill in as a utility player. Then came his big break. After the 1968 season, the Astros left Colbert unprotected in the expansion draft, giving the Padres the chance to gain his services. With the 18th pick of the draft, after selections such as Jose Arcia, Skip Guinn, and Al Santorini, the Padres nabbed Colbert.

After starting the season in a platoon role, Colbert caught the attention of his new manager, Preston Gomez. At first, the Padres planned to platoon Colbert with the lefty-hitting Bill Davis, who was six-feet, seven-inches tall and was known as “The Jolly Green Giant.” Something happened to change that plan. “And then,” Colbert said, “I got hot and hit home runs in five straight games. Preston Gomez came up to me and told me that I had earned the right to play every day.” Davis was soon traded, cementing Colbert’s newfound status.

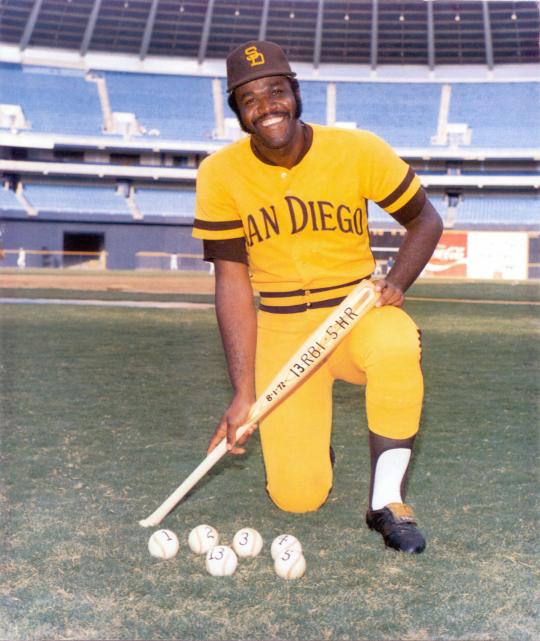

From 1969 to 1972, Colbert put up huge power numbers, twice hitting 38 home runs in a season and twice posting slugging percentages of better than .500. In 1972, his best year, he collected 111 RBI, accounting for an incredible 23 percent of the Padres’ run total for the season. (No one else on the Padres had as many as 50 RBI that season.) That 23 percent figure remains a major league record.

Colbert was never better than he was on Aug. 1 that season, when the Padres played a doubleheader in Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium. Colbert hit two home runs in the first game, and then smacked three more in the nightcap.

The fifth home run matched the mark set by his boyhood hero, Musial. (To make the story even better, Colbert was one of the fans in attendance at Sportsman’s Park the day in 1954 that Musial hit his five home runs.) Rather dramatically, Colbert hit the record-tying home run in the ninth inning against Cecil Upshaw, a right-handed reliever with a deceiving delivery. “I always had trouble against Cecil Upshaw, who threw underhanded,” Colbert explained during his visit to the Hall of Fame. “For some reason, he threw me an overhand fastball [in Atlanta]. Years later, I asked him why he did that. He said that he thought he could surprise me with it… Surprise!”

Colbert’s prime years with the Padres provided other memorable moments, including the infamous night when team owner Ray Kroc took to the microphone at San Diego Stadium. “Well, we had just gotten thumped in LA,” said Colbert, setting the scene. “And we came home and got thumped the first night. And we were getting thumped again. So I was the hitter, and somebody comes on the mike and says, ‘People of San Diego…’ It scared me, I thought it was God. You know, I thought, oh gosh, the rapture was coming, and I’m not ready. And he said, ‘I want to apologize for such stupid baseball playing.’ And about that time, a streaker ran onto the field, a guy with nothing on but a Viking helmet. And he did a little dance at second. Ray lost it and said, ‘Get him out of here! Get him out of here! People like that should be arrested and the key thrown away.’ Then he got composed again and said, ‘I just want you to know that we had more fans than LA and San Francisco tonight…but I never saw such stupid ballplaying in all my life.’ So in protest, I said to myself, I’m not swinging.’ I just stood there and I walked. The next guy did the same thing and he walked. So I yelled to the next guy, ‘We got a rally going.’ We scored five runs. He [Kroc] apologized to us later. And I told him, ‘You own us. You can say what you want.’ ”

After putting up a final productive season for the Padres in 1973, Colbert began to have considerable problems with his back; it was a congenital condition caused by degeneration of his vertebrae. His movements restricted, Colbert saw his batting average fall to .207 in 1974. That winter, the Padres unloaded their ailing slugger, sending him to the Detroit Tigers for a package of shortstop Eddie Brinkman, outfielder Dick Sharon and minor league pitcher Bob Strampe.

Colbert would spend short stints with the Tigers and Montreal Expos, but his chronic back problems sapped his effectiveness. In 1976, he wrapped up his career with Oakland. Although he went hitless in only five at-bats for the A’s, he loved playing for another controversial owner, one who made Kroc look like a wallflower. “As far as Charlie Finley, I loved Charlie Finley,” Colbert said without hesitation. “I thought he was awesome. When he traded for me, he told me that he always wanted me to play for him. He told me couldn’t afford me the next year [1977], but he wanted me to have a good time that year [1976]. He told me if I needed anything, just call him. He treated my wife and I very well.”

Colbert met his wife Kasey during that memorable stopover with the A’s. Nine children and 22 grandchildren later, they both served as ministers (Colbert was a chaplain for the Padres after his retirement) and co-owners of a company that provides advice and counseling to amateur athletes considering careers at the professional level.

“I love to pray,” said the soft-spoken but affable Colbert, who passed away on Jan 5, 2023. “And I love to teach. I love the involvement with other people.”

Bruce Markusen is the Manager of Digital and Outreach Learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum