- Home

- Our Stories

- When Baseball Stepped to the Plate for Finns

When Baseball Stepped to the Plate for Finns

Although the United States had not been directly involved with World War II hostilities by the last few months of 1939, the news of events halfway around the globe could not be ignored.

On Nov. 30, 1939 – a few months after the German invasion of Poland – the New York Times’ front-page headline bemoaned the invasion of Finland by the Soviet Union. The northern European nation, which gained independence from Russia less than 25 years earlier, dealt with a humanitarian crisis, as many Finns were forced to relocate from Soviet-occupied territories.

On March 17, 1940, baseball stepped to the plate to help out.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Help from the United States

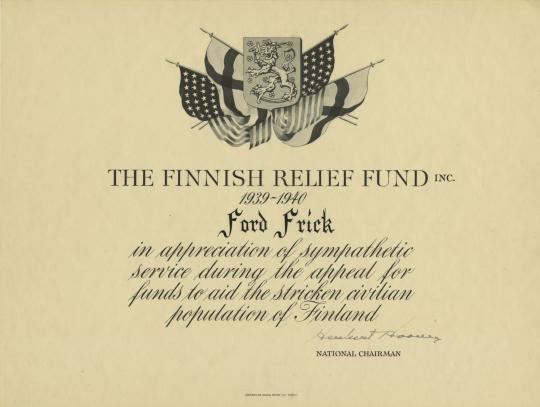

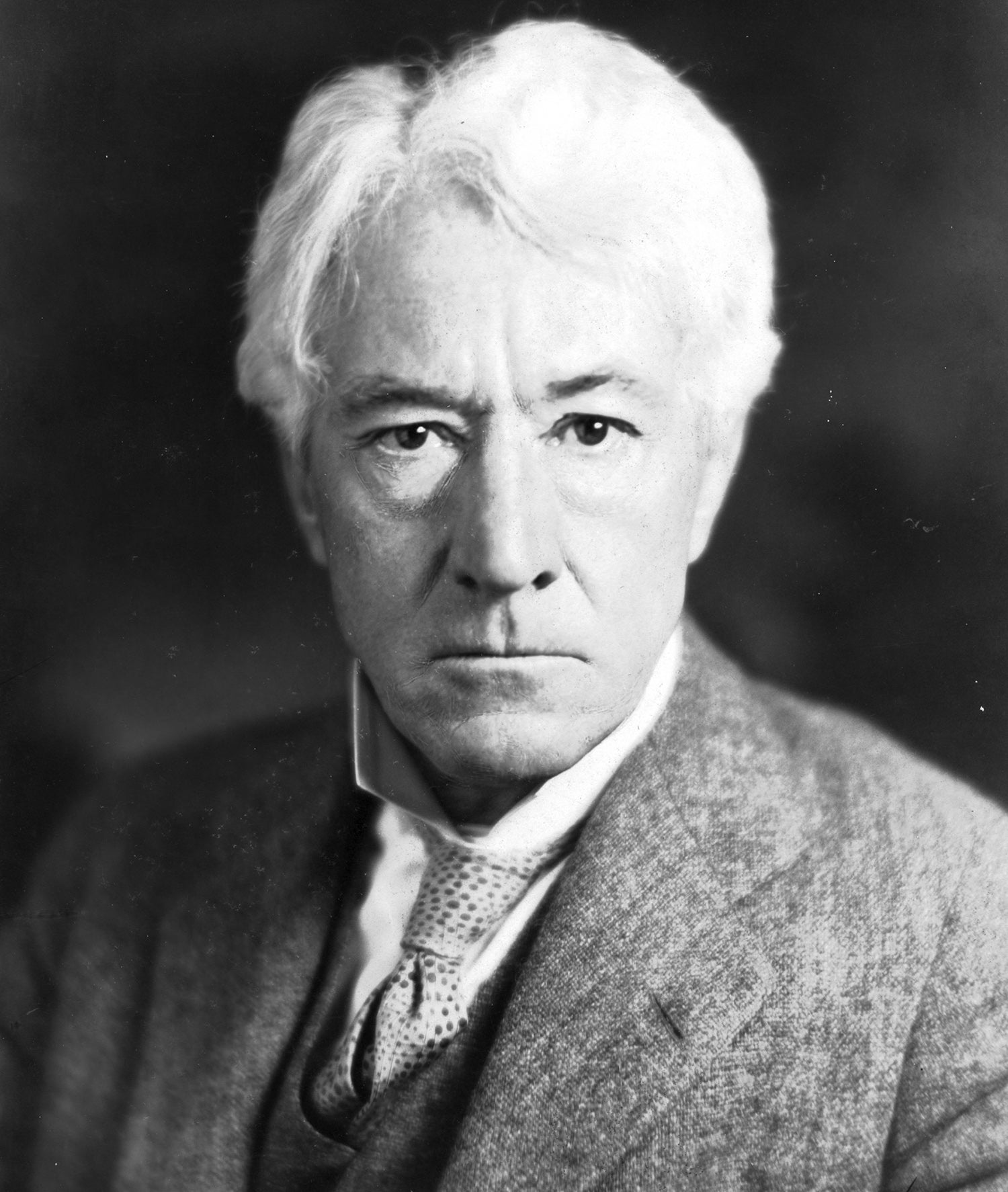

Along with their valiant, out-manned resistance in the face of a superior aggressor, the plight of the Finnish people prompted former United States president Herbert Hoover to insist upon action. He spearheaded fundraising and aid campaigns for the Finns. To coordinate the distribution of aid to Finland, Hoover organized the Finnish Relief Fund, working side-by-side with the American Red Cross’ independent relief efforts.

The first notion of baseball’s participation in the relief campaign came on Jan. 4, 1940, when Hoover met with New York City-area sportswriters at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. There, they pledged support to Hoover and New York World-Telegram sportswriter Joe Williams, whom Hoover placed in charge of the sports committee. It was thought there might be an all-star game, to be played during spring training, consisting of veterans and rookies from the 11 teams based in Florida.

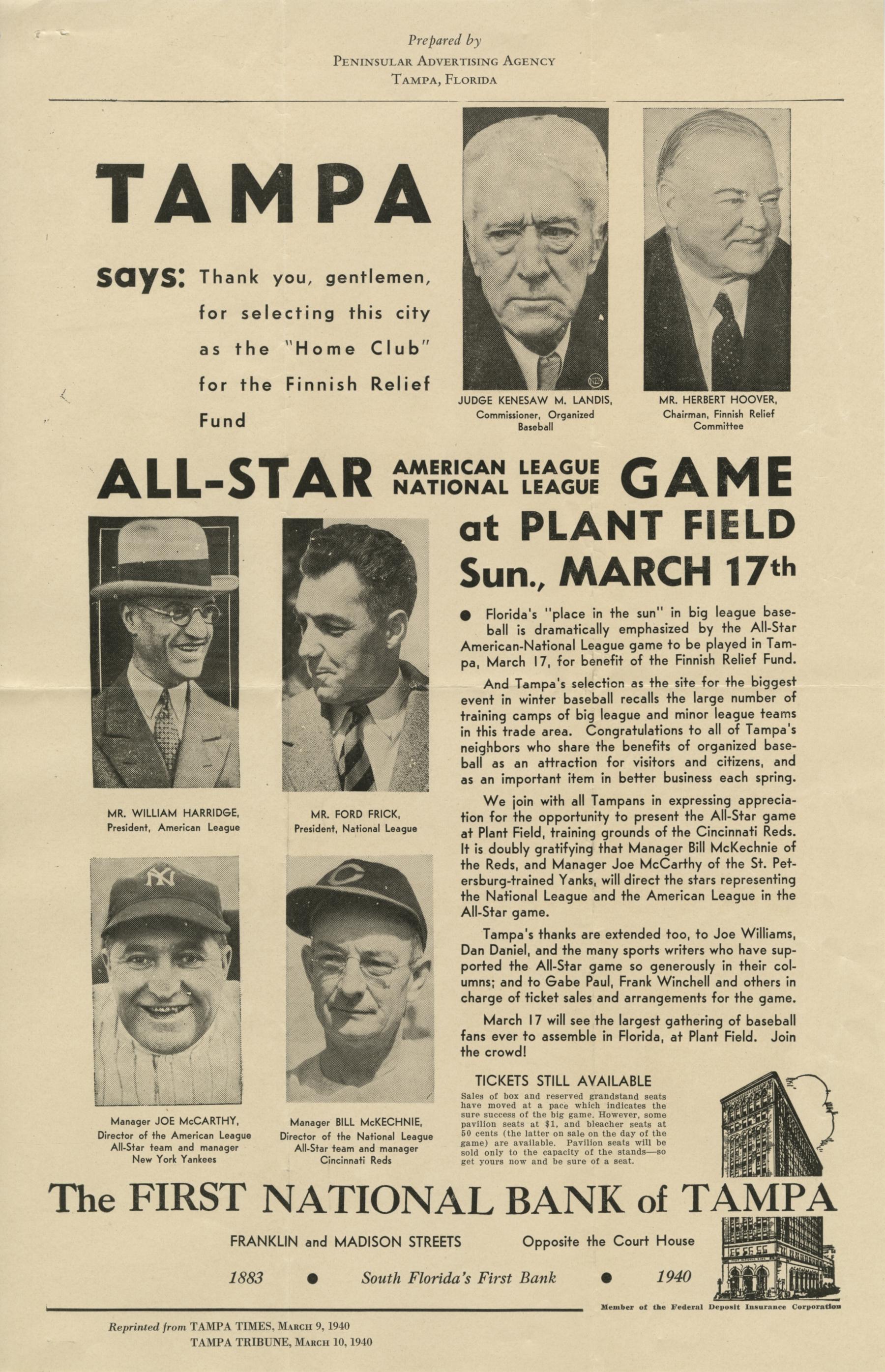

On Feb. 6, the idea would be one step closer to reality, as sportswriter Dan Daniel, chairman of the relief drive’s baseball committee, received word that the National League would participate. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and the American League had previously pledged support. After deciding Miami-area ballparks lacked the proper facilities, the cities of Tampa and St. Petersburg, Fla., were considered for the site of the game. Daniel wanted “to have a place where it could be done right.” The baseball writers would vote for participants.

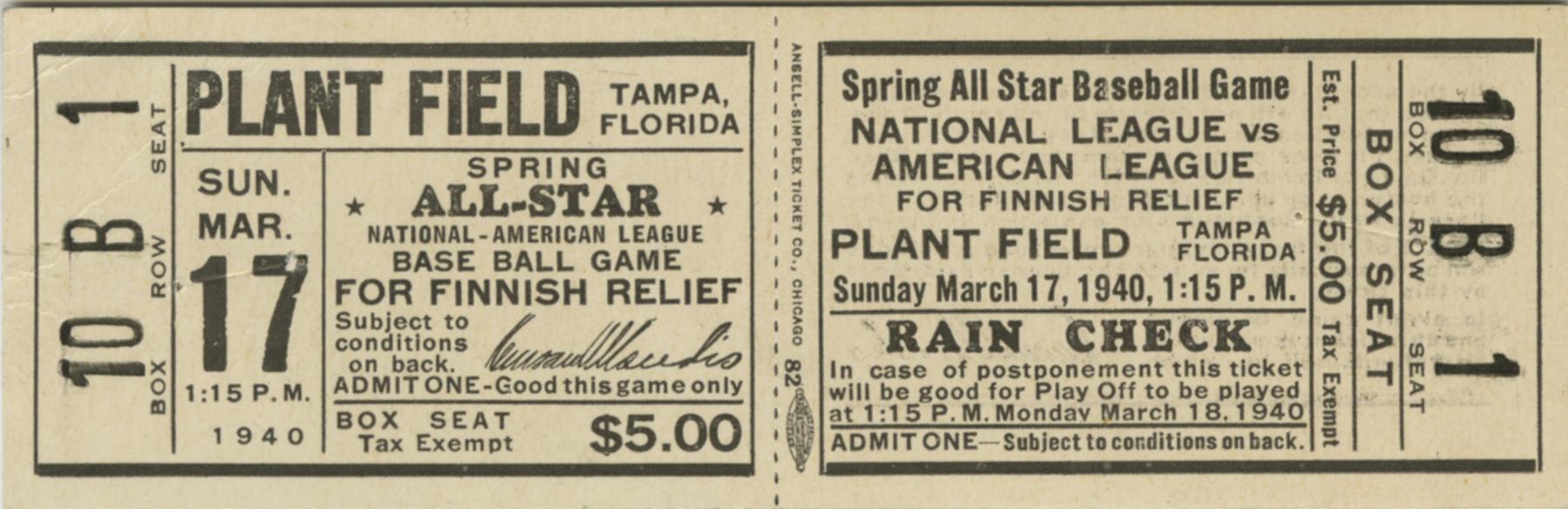

Just over a week later, the date and place were set: March 17 in Tampa. The ballpark in Tampa, Plant Field, could seat several thousand more fans than the one in St. Petersburg, and temporary seating could increase the capacity to about 20,000. While the focus was on using players training in Florida, Williams suggested bringing in players from the clubs training on the west coast. The idea ultimately was not accepted, though those players, too, would participate in their own way.

Landis formally approved the all-star game at a meeting of team representatives on Feb. 23 and placed Cincinnati’s Gabe Paul in charge of handling tickets for the game. Baseball writer Tom Swope handled press arrangements. Joe McCarthy of the Yankees and Bill McKechnie of the Reds, opposing skippers in the 1939 World Series, were tapped to pilot their respective league’s team. The National League won home-field advantage in a coin flip, and Landis decided each team would have 20 players: six pitchers, three catchers, six infielders, and five outfielders.

A team of stars

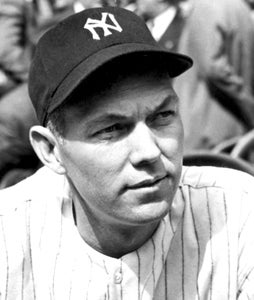

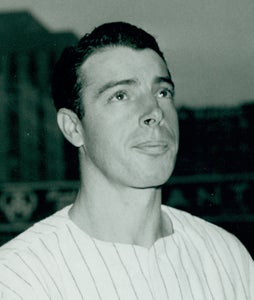

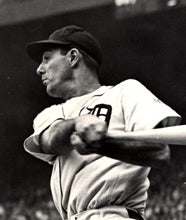

When the writers convened in Tampa on March 1 to vote on the teams, they were given the opportunity to choose 25 players instead of 20. The offensive expectations for the American League were high, particularly with a roster boasting Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Jimmie Foxx, and Hank Greenberg. Between the two teams, including both managers, there was a total of 22 future Hall of Famers on the original rosters.

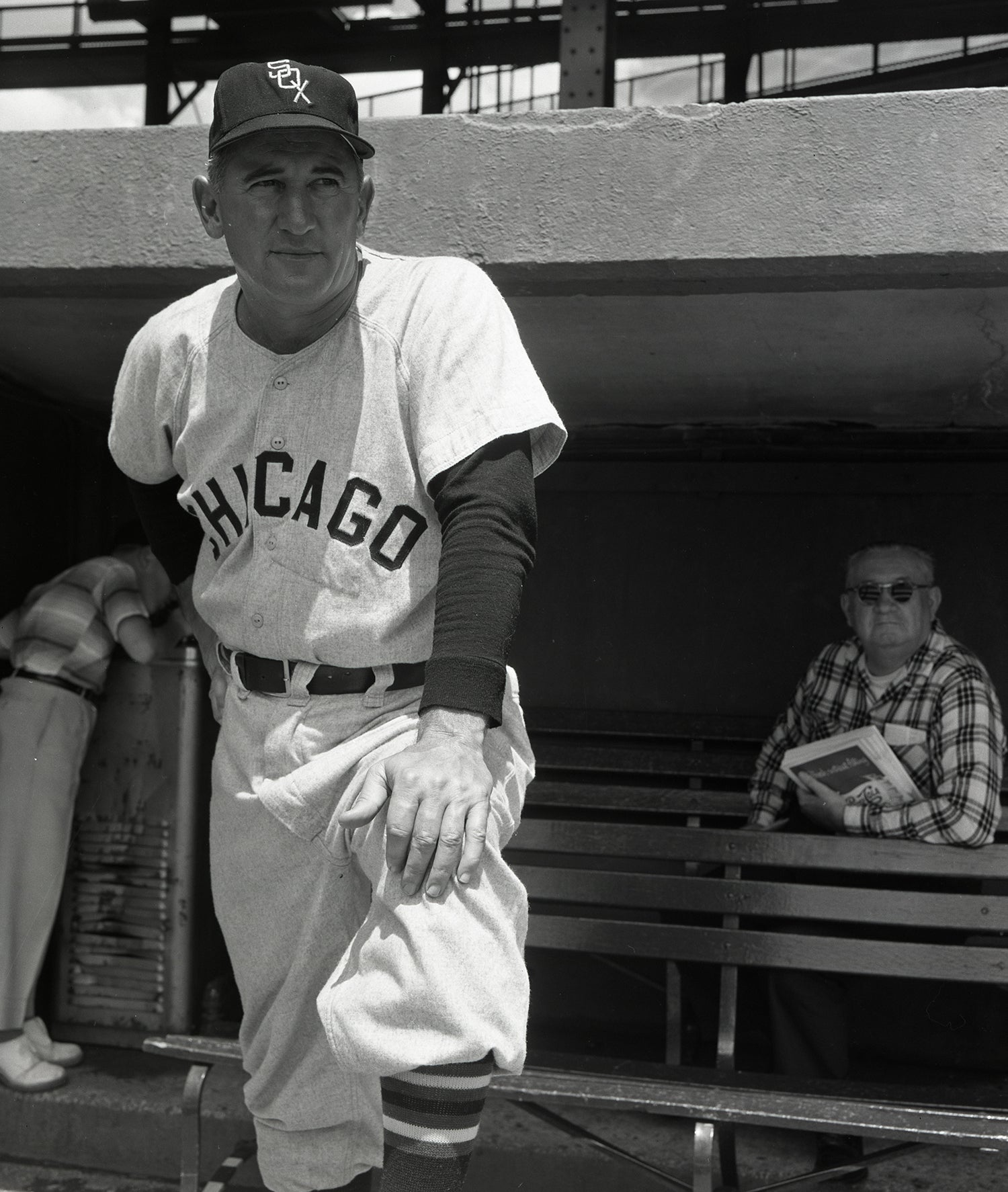

On the opposite side of the country, the major leaguers training on the west coast offered their services toward the Finnish Relief Fund. On March 10, in Los Angeles, an all-star team composed of players from the Athletics, Cubs, White Sox, and Pirates defeated a Pacific Coast League all-star team. The game, played at Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field, went 4 to 1 in favor of the major leaguers and attracted over 9,700 fans. Eight future Hall of Famers played in the game for the major leaguers, with another, Frankie Frisch, managing the team, and a recent inductee, Honus Wagner, serving as a coach.

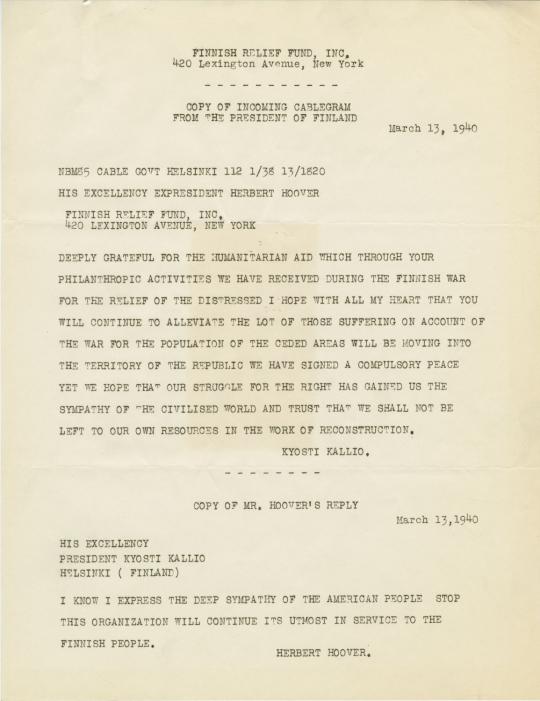

But the main event, a week later, almost never happened. On March 12, Finland and the Soviet Union signed a peace treaty, which went into effect the following day. It was up to Landis to decide whether to proceed with the game, and he chose to do so.

“There must be some relief funds remaining from Herbert Hoover’s efforts on behalf of the Finns, and we’ll let the proceeds of that game go to this fund – never for soldiers or arms, anyway, but for the relief of non-combatants, and they are still in need,” Landis said. “So we will play the game as planned with the same stars, same managers, and everything else the same.”

National League prevails

Despite being a heavy underdog – and with most people expecting a slugfest – the National League pulled an upset with a 2-1 victory. More than 13,000 fans attended the game, making it the largest baseball crowd in the history of Florida, and over $20,000 was raised for the Finnish Relief Fund. Radio listeners could even listen in, as the game was broadcast by Red Barber on the Mutual Network.

The teams only managed 11 hits – all singles – between them, but it was the base hit from Brooklyn Dodger Pete Coscarart that made the difference. In the bottom of the ninth inning, he lined a Bob Feller pitch through the infield to drive in Boston Bees catcher and Tampa native Al Lopez with the winning run. The Giants’ Harry Gumbert pitched the top of the ninth for the win. Yankees Bill Dickey and Frank Crosetti were the only batters with multiple hits. All told, 13 future Hall of Famers ended up playing in the game.

The game to aid the Finnish Relief Fund could be considered a success, but opinions differed as to the lasting worthiness of an all-star game during spring training. At the joint session of the major leagues in December, the National League stated its desire to continue playing the game, with proceeds going to equip trainee baseball teams. The American League did not have such a desire, and neither did Landis, who cast the deciding ballot against the idea. The sides felt the two leagues could work with military authorities to determine a plan where baseball could best help trainees.

Kyösti Kallio, President of Finland, sent this cablegram to former U.S. president Herbert Hoover on March 13, 1940. He thanked the American people and the Finnish Relief Fund for their humanitarian aid and philanthropy. The cablegram was sent just after Finland reached a peace agreement with the Soviet Union, and Kallio’s message was to be read at the all-star game. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

Within a year of the joint meetings, the United States would find itself engaged in the global conflict, and several of the all-stars, including Feller, Greenberg, and Ted Williams, would find themselves taking a completely different role in the war effort.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum