- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1981 Topps Lary Sorensen

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Lary Sorensen

By 1981, the Topps Company no longer was the lone producer of cards featuring major league baseball players.

Donruss entered the market and the Fleer Corporation re-entered it, giving Topps its first competition since Fleer departed the card business in 1963.

Not to sit idly by, after issuing a traditional 726-card base set, Topps came out with a 132-card “Traded” series during the season, highlighting those players who had switched teams as well as rookies making their major league debuts. Although Topps had produced a couple of traded sets in the mid-1970s, the 1981 Traded series was the first of its kind, issued exclusively as a boxed set.

One of those 1981 Topps Traded cards was of Lary Sorensen, who would go on to help both the St. Louis Cardinals and the Milwaukee Brewers reach the 1982 World Series – without playing for either team that season.

Let’s explain. The right-handed pitcher was involved in two trades that brought key players to both organizations.

First, in December of 1980, during the record-setting Winter Meetings that featured trades that involved more than 70 players, Sorensen was dealt from Milwaukee to St. Louis in a seven-player trade that sent right-handers Rollie Fingers and Pete Vuckovich and veteran catcher Ted Simmons to the Brewers. That trio proved instrumental in the Brewers winning the 1982 American League pennant.

Then, after spending the 1981 season in St. Louis, Sorensen was sent to the Cleveland Indians in a three-team deal that brought outfielder Lonnie Smith to the Cardinals. Smith was the catalyst for a speed-oriented St. Louis squad that won the 1982 National League pennant and went on to beat the Brewers in a memorable seven-game World Series.

Sorensen has often quipped that he felt he deserved a share of the postseason bonuses from both clubs.

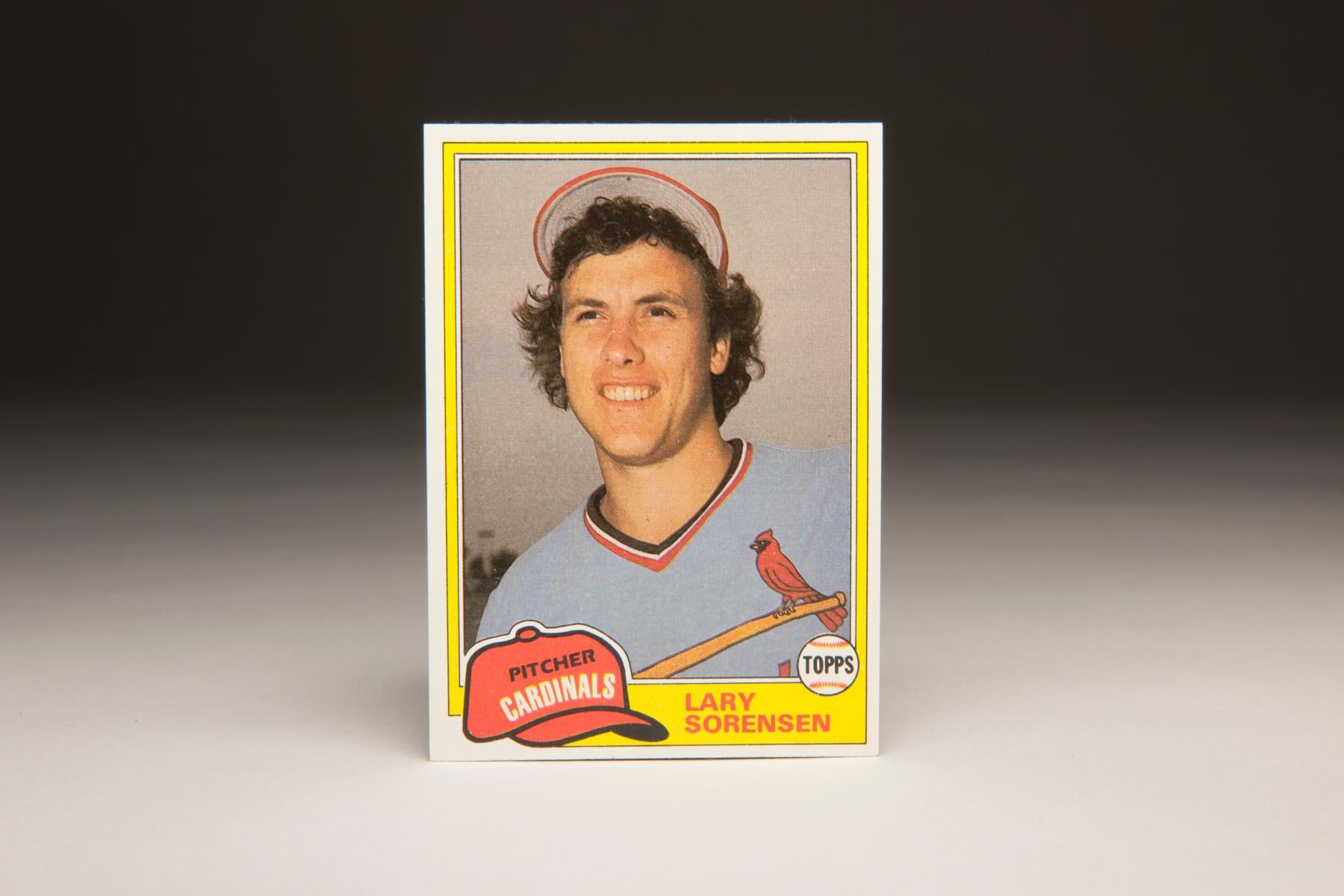

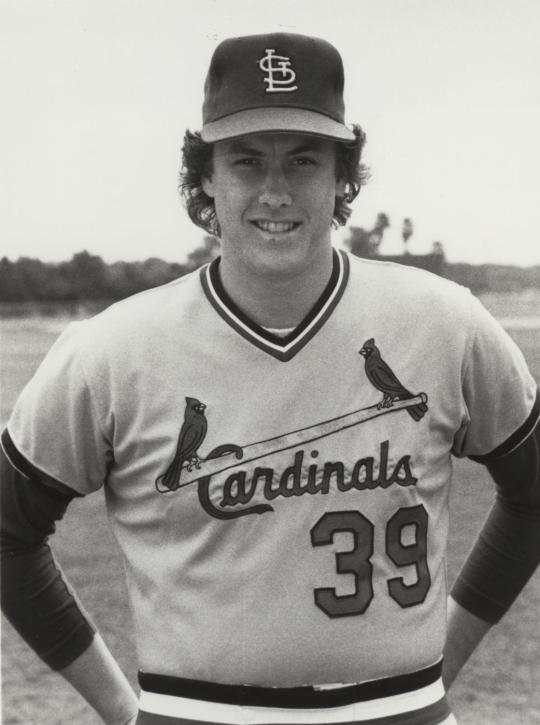

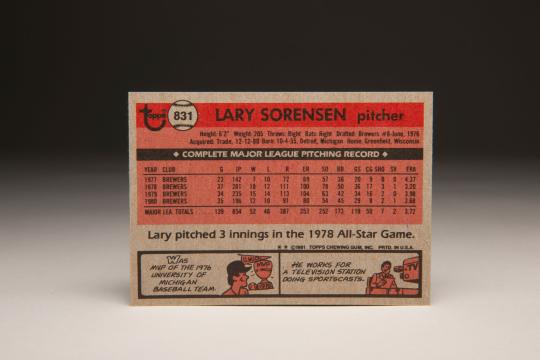

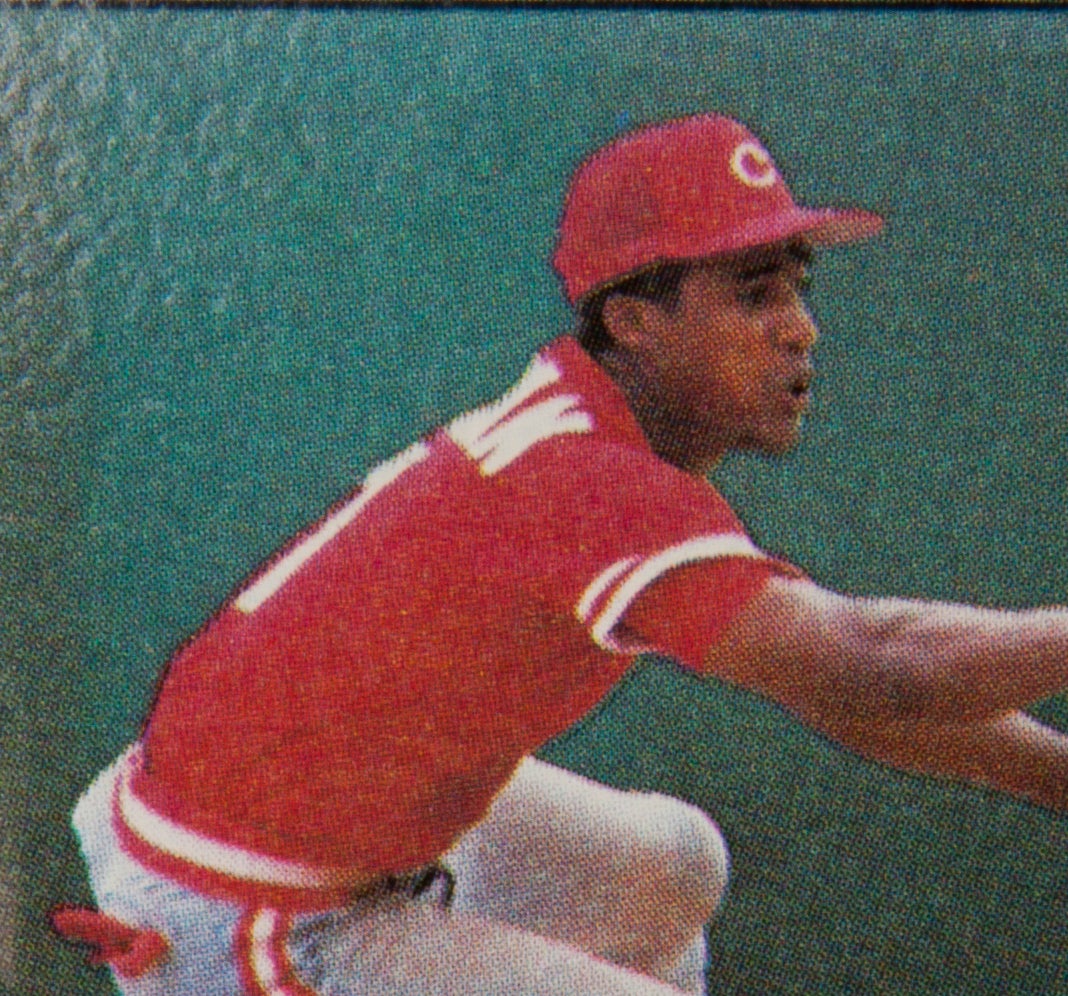

In the 1981 Topps base set, Sorensen is featured on card No. 379, shown pitching as a member of the Brewers. He is No. 831 in the Traded series, appearing as a Cardinal with a head-and-shoulders photograph while flashing his distinctive smile.

Sorensen made his major league debut with Milwaukee in 1977. The following year, he was an American League All-Star and pitched three shutout innings in the Midsummer Classic, allowing only an infield single before retiring nine batters in a row, including such stars as Pete Rose, George Foster and Steve Garvey.

Sorensen won a career-high 18 games and had a career-low 3.21 ERA for the Brewers in 1978. He ranked fifth in the league. in complete games in both 1978 (17) and 1979 (16). Meanwhile, Milwaukee went from an afterthought to a contender in the rugged American League East.

In his lone season in St. Louis in 1981, Sorensen posted a 3.27 ERA and surrendered just three home runs in just over 140 innings pitched. The Cardinals had the best overall record in the National League at 59-43, but they finished in second place in both halves of the split season that was the result of a 50-day players’ strike from June 12 through July 31 and did not make the postseason. In both halves, St. Louis played fewer games than the champion (Philadelphia in the first half and Montreal in the second half) and could have caught or surpassed the winner with the opportunity to play the same number of games.

Sorensen pitched for the Indians in 1982 and 1983 and then had stints with the Oakland A’s (1984), Chicago Cubs (1985), Montreal Expos (1987) and San Francisco Giants (1988). His career statistics included a 93-103 record and a 4.15 ERA with 69 complete games and 10 shutouts in 346 games (235 starts), amassing 1,736 1/3 innings pitched. Known for his control, Sorensen averaged just 2.084 walks per nine innings.

At the same time, Topps continued to produce 132-card Traded series, which became a yearly staple of the company; Sorensen is included in the 1982 and 1984 Traded sets.

Throughout his career, Sorensen’s engaging personality made him popular among fans. He was well-spoken, having studied communications at the University of Michigan, and always provided good quotes for the media. He also was generous with his time in the community.

Despite his fun-loving disposition and big-heartedness, Sorensen battled demons that were generally hidden from the media. Sorensen struggled with both alcohol and drug use at various times. (In 1986, he was one of 10 major league players to receive a suspension for his admission of cocaine use at the Pittsburgh drug trials.) His drinking problems persisted after his playing days, when he made the transition to television and radio broadcasting. He called the College World Series and Major League Baseball on ESPN from 1990 to 1994, and then moved on to the Detroit Tigers, calling games on WJR Radio from 1995 to 1998.

Alcoholism ultimately cost Sorensen his broadcasting career, his marriage, and his dignity. He hit rock bottom in 2008. Sorensen was driving in Roseville, Mich., when he lost control of his car and ended up in a ditch. A while later, he was found behind the wheel, completely unconscious and with a blood-alcohol level of .48. In two senses, he was fortunate to be alive, not only because he had survived the crash, but also because of the remarkable level of alcohol in his system. Anything above .31 can be lethal, but Sorensen somehow withstood it.

After being treated at a hospital, Sorensen went to prison, having been arrested a seventh time for driving under the influence. For Sorensen, it was his third stint behind bars. In 2003, he had spent 30 days in jail. And then in 2004, he began a stint of 23 months in prison, again because of drunk driving.

Sorensen’s third release from prison came in 2009, but he did not really begin to turn his life around until 2011. That’s when he moved from his home state of Michigan to Winston-Salem, N.C., where his sister, Lynn Sutton, lived. Lynn offered him a kind of support system that had been lacking in Michigan. Sorensen also met his second wife, Elaine, who was a member of the church choir at Calvary Baptist Church. In addition to his budding relationship with Elaine, Sorensen enjoyed both the music and the sermons that he heard at Calvary Baptist Church.

Thanks to new friendships with church members, along with a rekindled friendship from his past, Sorensen turned his contacts into a broadcasting job with Wake Forest University. From there, he found a job as a color announcer with the Winston-Salem Dash, the Class A affiliate of the Chicago White Sox. Thanks to his work ethic and his willingness to prepare for each broadcast, I believe Sorensen has become one of the better minor-league broadcasters in the game today.

Most importantly, Sorensen has been sober for nearly two years. Having celebrated his 60th birthday on Oct. 4, he is happy and healthy in his post-baseball life and regularly showing that same smile from his 1981 Topps Traded card.

Tom Schott is a baseball historian and collector.