- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Carmen Fanzone

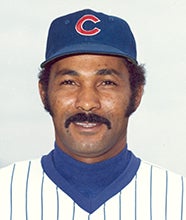

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Carmen Fanzone

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

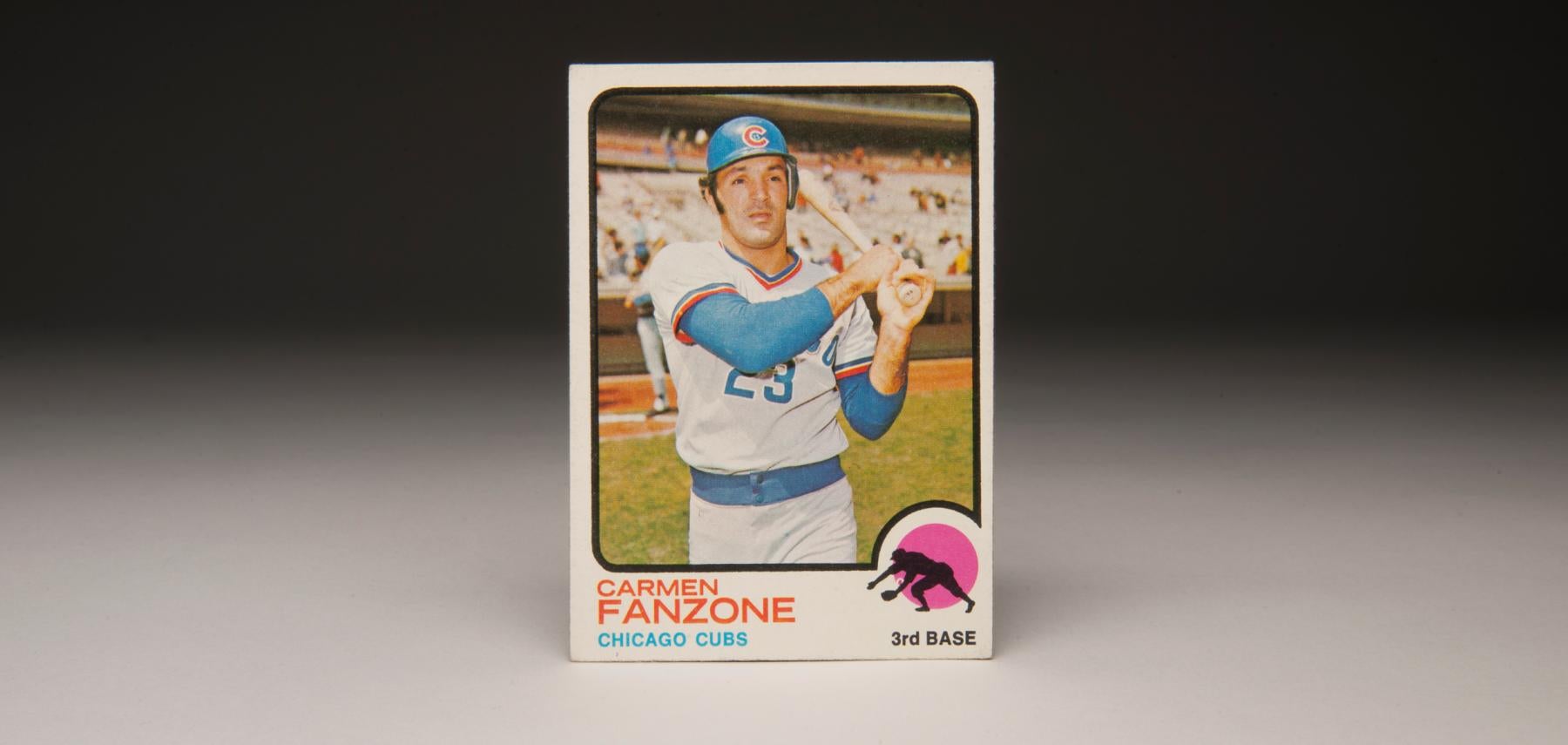

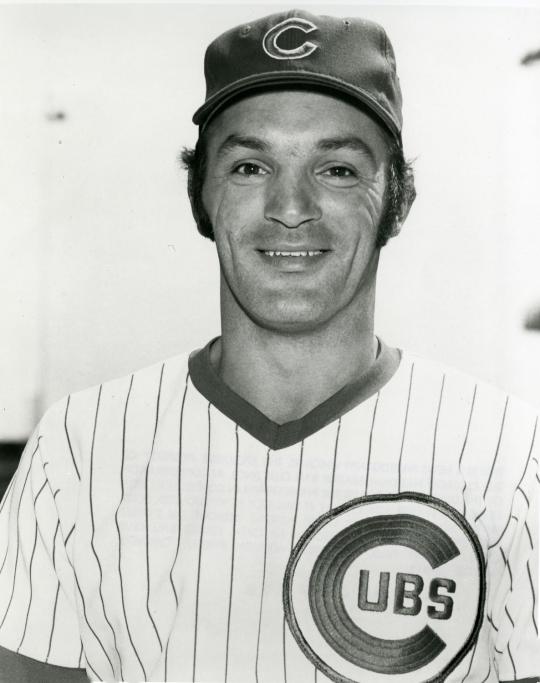

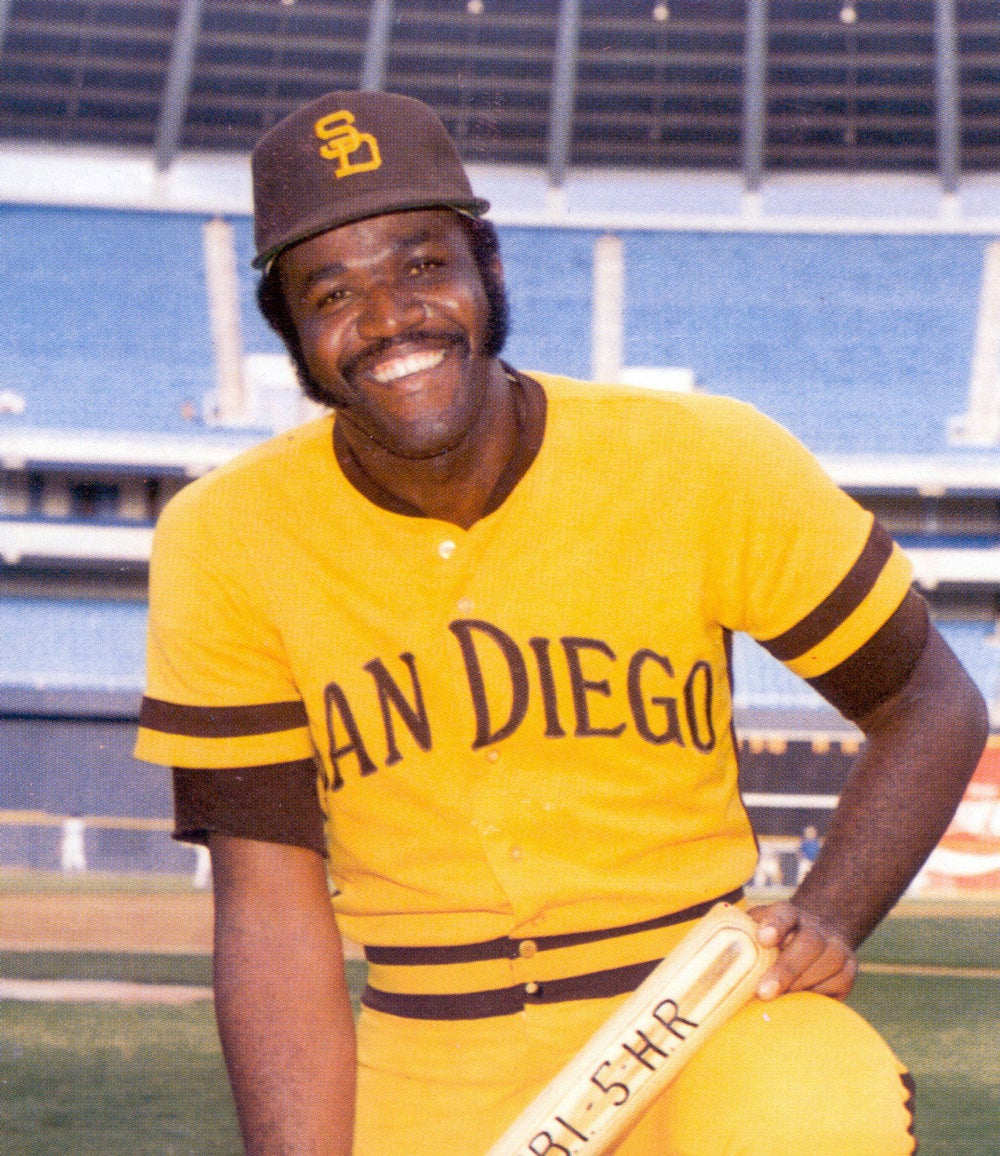

In posing for his 1973 Topps card in a photograph that was taken at Shea Stadium, Carmen Fanzone is shown clearly holding a bat. For a moment, imagine that bat to be a trumpet. In a sense, that would have been a far more appropriate—and creative—choice for a Fanzone baseball card. While the third baseman-second baseman often struggled with the bat—arguably the most important instrument for an everyday player in the major leagues—he repeatedly proved himself more than capable when it came to handling a musical instrument.

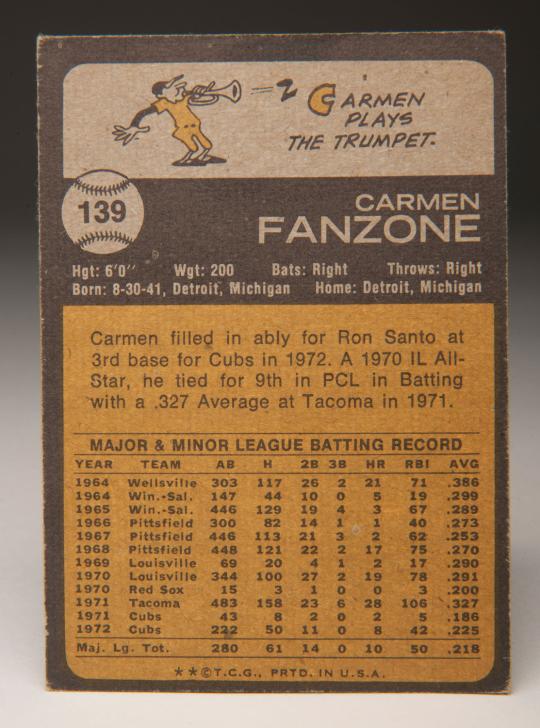

Like many major leaguers, Fanzone found the bat to be difficult to master, but in contrast to most big leaguers, he had little trouble in the world of music. At the tender age of 8, Fanzone started playing the trumpet. In high school, he performed capably for a band in Detroit, eventually majoring in music at Central Michigan University. Fanzone’s dedication to music didn’t prevent him from pursuing baseball, however. “If I wasn't going to a band rehearsal,” Fanzone told writer Jerry Crowe of the Los Angeles Times, “I was going to a baseball practice, or vice versa.”

As a ballplayer, Fanzone began his professional career in 1964, when the Boston Red Sox signed him as an amateur free agent. (It was the final year before the amateur draft, so Fanzone had his choice of signing with any team.) The Red Sox signed him to their NY-Penn League affiliate at Wellsville (located about 200 miles from Cooperstown); Fanzone immediately made a strong impression by hitting 21 home runs, putting up a 1.165 OPS, and playing three different positions: second base, shortstop, and third base. The Red Sox liked what they saw so much that they promoted him to full-season A-ball by the end of his first summer.

As well as Fanzone had played in Wellsville, he struggled to match that performance as he moved up the Red Sox’s ladder. Eventually settling in at third base, Fanzone continued to hit for a high average, but without the power the Sox had seen in the NY-Penn League. As a result, it took Fanzone awhile to complete the climb to Boston—six years to be exact. Curiously, Fanzone faced some resentment at various times in the minor leagues. While his major league managers would never tell him to abandon his musical pursuits, he did receive some blowback from some of his minor league skippers. At least one manager told Fanzone to give up music entirely and concentrate on baseball.

In spite of the resentment, Fanzone continued to pursue both of his loves. The dream paid off in 1970 when Fanzone received a midseason call-up to Boston. He was hardly a young prospect at this point, 28 years of age, well past the point of being considered a phenom. But it was still the major leagues, an elusive goal for the vast majority of minor league ballplayers.

Fanzone’s lack of power and speed had concerned some within the organization, but he did his best to make up for the absence of those traits by hustling at all times and maintaining an inspired attitude. One of those taking notice was Hall of Famer Ted Williams, who served as a spring training instructor for the Red Sox before becoming manager of the Washington Senators. One spring, in about 1967 or ’68, Williams took Fanzone under his wing and gave him some of his patented hitting advice. “It was like God was talking to me,” Fanzone told the Los Angeles Times.

His apprenticeship completed, Fanzone would make his debut at third base, in the middle of the 1970 season, while filling in occasionally for starting third baseman Rico Petrocelli. Of course, there was no way for Fanzone to replace Petrocelli, one of the team’s heroes from the 1967 “Impossible Dream” team and a player who was still putting up prime power numbers in 1970. With Petrocelli in the midst of a season in which he would hit 29 home runs and pile up 103 RBIs, Fanzone found himself blocked. The only other realistic option was second base, but the Red Sox featured a capable young veteran at that position in the form of Mike Andrews, a solid defender who also hit with power. There was simply nowhere for Fanzone to go—other than outside of the organization.

That winter, in a move that surprised no one, the Red Sox traded Fanzone. They sent him to the Chicago Cubs for veteran infielder Phil Gagliano, an older player who had already adjusted to a part-time role with the Cubs and the St. Louis Cardinals. Now out of Boston, Fanzone hoped for more playing time in the National League.

It didn’t happen, at least not initially. Like the Red Sox, the Cubs already had established regulars at third base, where Hall of Famer Ron Santo resided, and at second base, the home of Cubs mainstay Glenn Beckert. So it was back to Triple-A ball, more specifically an assignment to Tacoma, the Cubs’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. Known as a hitter-friendly league, the PCL proved to be good fit for an experienced player like Fanzone, who reached career highs in batting average (.327), home runs (28), and RBIs (106).

As a reward for his fine summer in Tacoma, the Cubs called Fanzone up in September. The Cubs resorted to making a utility player of Fanzone, with a plan to use him off the bench as a combination infielder/outfielder. In his very first at-bat with the Cubs, he entered the game as a pinch-hitter against Pittsburgh’s Steve Blass and delivered a home run at Three Rivers Stadium.

Fanzone would hit one more home run that September while compiling a batting average of .186. Still, the Cubs liked Fanzone’s versatility, which allowed him to appear in games at third base, first base, and the outfield corners. So in 1972, the Cubs included Fanzone on their Opening Day roster as a utility man, with the job of backing up players like Santo, first baseman Jim Hickman, and outfielders Billy Williams and Jose Cardenal.

For the first time in his career, Fanzone would not spend a day in the minor leagues. Maintaining his roster spot in Chicago throughout the summer, Fanzone hit only .225 but did provide protection at five different positions while appearing in 86 games.

Playing in Chicago provided an extra benefit. Since the Cubs played all of their home games in the daytime hours at Wrigley Field, Fanzone was now free to pursue musical gigs at night. Once the game ended, Fanzone typically made his way to a local establishment to play jazz sessions. As Fanzone would say many years later, “it was good therapy for me.” The Cubs seemed to respect Fanzone’s musical talents, as they asked him to perform the National Anthem with his trumpet on more than one occasion.

Typically, Fanzone played for the Salvation Army during the off-season and taught music classes in the winter. He also played the trumpet at night spots in Chicago and area high schools. He specialized in jazz music, with a little classical thrown in for good measure.

As much as the music meant to him, Fanzone made baseball his first priority during the season. Thanks to his season-long stint in Chicago in 1972, Fanzone earned his first appearance on a Topps card as part of the 1973 set. The photograph, taken during one of the Cubs’ trips to New York in 1972, shows off the team’s new road uniform. By 1972, the Cubs had made the switch from flannel button-down jerseys to polyester pullovers, while adopting a thick, blue elastic waistband, a replacement for the traditional black belt. By this time, Fanzone would have been willing to wear a cumber bun as part of his uniform; he was simply grateful to call himself a fulltime major leaguer.

With his first Topps card appearance set in stone, Fanzone put up his best season in 1973. Again fulling a jack-of-all-trades role, he hit .273 and posted an OPS of .797, a terrific number for a bench player. With Santo now 33 and showing some signs of wear and tear, some speculated that Fanzone might soon take over the third base job. Given his offensive flashes, along with a reputation for good defensive play at the hot corner, the Cubs thought they might have found a successor to the aging Santo.

It didn’t happen. That October, the Cubs traded Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins to the Texas Rangers for a package that included hot shot third baseman Bill Madlock. It was not Fanzone but Madlock succeeding Santo, who was soon traded to the crosstown White Sox.

Once again returning in a reserve role, a discouraged Fanzone hit only .190 and reached base just 26 percent of the time in 1974. Those numbers were not sustainable, leading to the Cubs’ decision to release Fanzone in December.

At 33 years old, Fanzone did not want to stop playing. He found some work in the minor leagues, signing a contract with the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders, the Triple-A affiliate of the San Diego Padres. At the time, the Islanders made a habit of signing veterans, making them a haven for major league castoffs. Veteran players enjoyed life with the Islanders, who provided a fringe benefit in the form of the warm sun and endless beaches of Honolulu. In 1975, the Islanders employed several former big leaguers, including Fanzone, catcher Chris Cannizzaro, infielders Steve Huntz and Sonny Jackson and and outfielder Rod Gaspar.

On paper, the move to Hawaii looked good, but Fanzone played only sparingly and didn’t hit much. A .217 batting average, combined with a severe ankle injury in midseason, convinced everybody that it was time to retire.

In contrast to many players, Fanzone had little trouble in making the transition from ballplayer to real life. After leaving the Islanders, Fanzone became a fulltime musical performer. In one of his more notable gigs, he played trumpet for the Baja Marimba Band at the Fairmount Hotel in New Orleans. The gig lasted two full years.

Even 40 years after the end of his baseball career, Fanzone still dabbles in music, though he spends much of his time working as a troubleshooter for the Los Angeles chapter of the American Federation of Musicians. (The federation is a union for musicians.) He maintains an office in Hollywood; the room is filled with photographs of celebrity musicians and former teammates, a reminder of the many “names” he has met along the way. Though he never did become a musical superstar, Fanzone has certainly emerged as one of the most successful athletes-turned-musicians in sports history. And he has no regrets about splitting his pursuits to include both baseball and the band.

For many players, baseball is everything. But for a music man like Carmen Fanzone, there is clearly life after baseball.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame