- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1971 Topps Joe Morgan

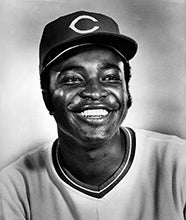

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Joe Morgan

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

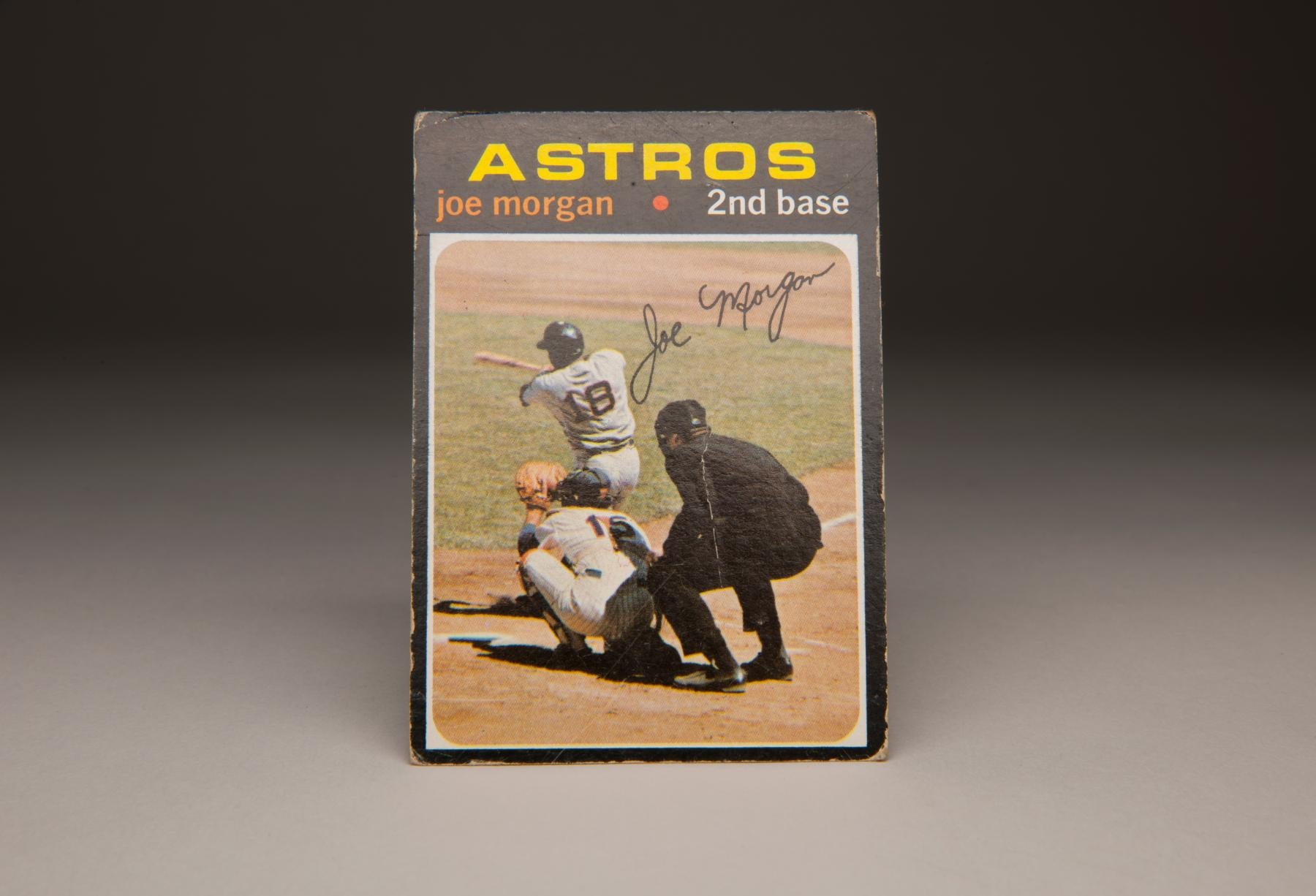

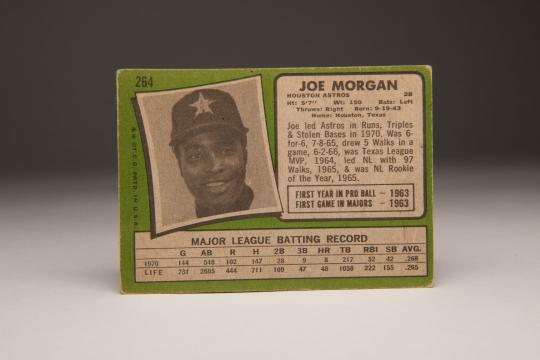

It’s hard to believe in retrospect, but the Topps Company did not begin to use color action photography on its cards until 1971, or some 19 years after the company’s first full set produced in 1952. The 1971 set, which was also distinctive for its use of black borders, featured no fewer than 52 action shots of individual players. It was a nice way to diversify player cards, which had consisted of profiles, head-on photographs and poses for the better part of two decades.

The group of 1971 action shots includes a number of terrific images. There is the hardworking Jerry Grote card that was featured in an earlier Card Corner, a wonderful shot of Thurman Munson trying to apply a dust-filled tag on Oakland A’s pitcher Chuck Dobson, a nifty card of Philadelphia Phillies left-hander Chris Short throwing a pitch against the backdrop of the “Alpo” sign at Connie Mack Stadium, and a resplendent shot of Felipe Alou in mid-swing while wearing the glorious green and gold colors of the A’s.

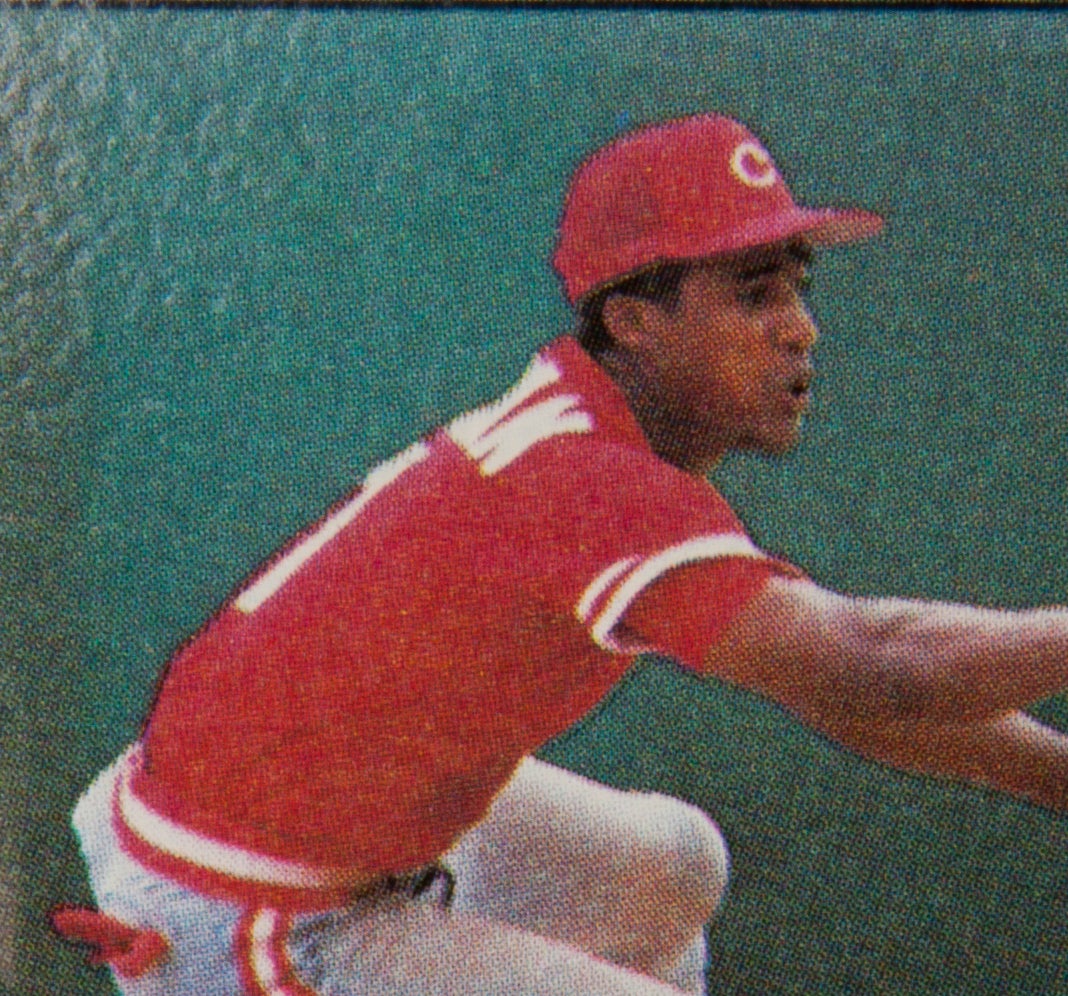

These are all great cards, and deserving of further exploration, but another favorite in the 1971 set gives us an offbeat look at a Hall of Famer. The Joe Morgan card is rather unusual in that it does not show us the player’s face, making it reminiscent of the 1973 Johnny Bench, which follows the back side of the Hall of Fame catcher as he pursues a foul pop while nearly running into the opposition dugout. For some collectors, the lack of a face within the photo is a black mark against the card, but not for me, especially with regard to a famous player. Stars are so well known that we already have a good idea as to what they look like; we don’t need each and every one of their cards to give us a close-up of their facial features. Sometimes it is the action portrayed on the card that drives our interest, and this 1971 card, just like the 1973 Bench, succeeds in doing just that.

Numbered 264 in the set, the Morgan card shows him in the middle of a level swing, as he tries to connect against a pitch up in the strike zone. (The only regret is that the card doesn’t show Morgan executing his trademark elbow flap, but you can’t have everything on a card.) The photo, while it runs against the grain, is interesting because of the juxtaposition between Morgan at bat, the catcher behind the plate (Grote of the New York Mets) and the severely crouched home plate umpire (who remains unknown). We rarely see this perspective on television anymore; we almost always see hitters from the vantage point of the center field lens or from the dugout camera on the side. But this card gives us something different, the viewpoint of someone who is watching the game from the box seats located right behind the home plate screen. It allows us to see just how close the batter, catcher, and umpire are to each other. Yes, it is an unusual angle of this home plate cluster, but it is fascinating, too.

Morgan’s 1971 card also calls to mind the subject of the Winter Meetings. It was at the 1971 Winter Meetings that Morgan and a host of other baseball stars traded uniforms in what would turn out to be a history-making get-together of general managers and owners.

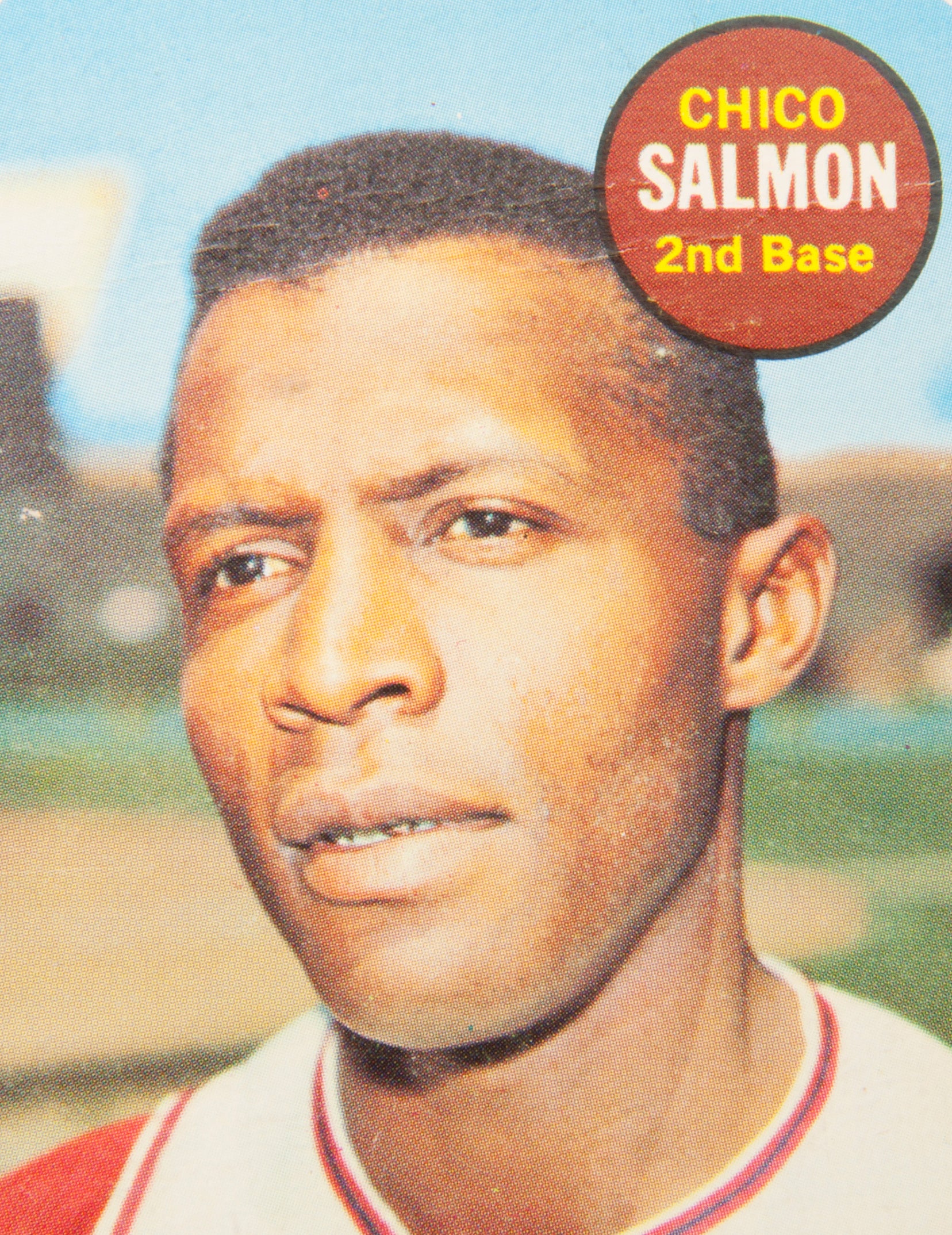

The 1971 Winter Meetings started on November 29 and concluded on December 3. For five days, the general managers of the 24 major league teams congregated at the Arizona Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Ariz. It did not take long for the GMs to get down to business. On the very first day of the meetings, six teams came together on three trades, all significant. The biggest trade of the day was a full-scale blockbuster between the Cincinnati Reds and the Houston Astros. The Reds sent power-hitting first baseman Lee May and infielders Tommy Helms and Jimmy Stewart (no relation to the actor) to the Astros for Morgan, fellow infielder Denis Menke, outfielders Cesar Geronimo and Ed Armbrister, and right-handed pitcher Jack Billingham.

At the time, Lee May was the most well-known player of the eight in the superswap, leading some to speculate that the Astros had won the trade. That analysis turned out to be dead wrong. In the short term, the Reds managed to revamp their infield, making it more athletic and better defensively. In dispatching with May, Reds general manager Bob Howsam cleared out first base for Tony Perez, who had been playing out of position at third base. Menke, a better fielder with more range at the hot corner, strengthened the left side of the Reds’ infield.

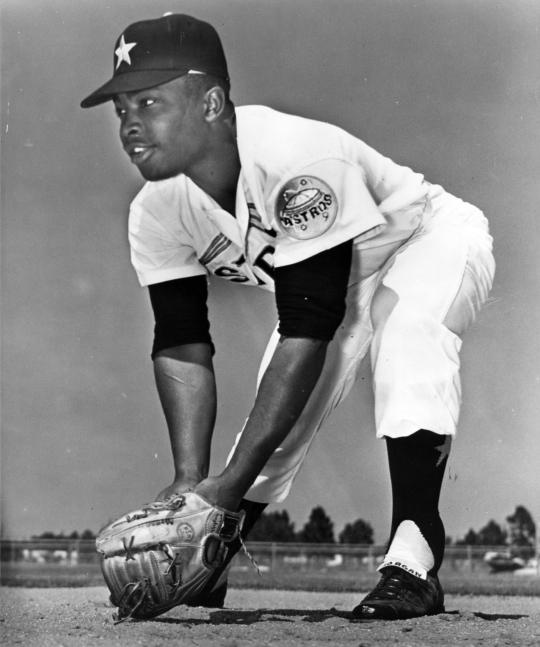

The biggest upgrade would come at second base, where Morgan replaced Helms. On the surface, Morgan was coming off a season in which he had batted .256 with the Astros. Still, he was a good player—and about to become a star in Cincinnati.

The Reds certainly understood what Morgan could provide them. When a reporter asked Cincinnati skipper Sparky Anderson about Morgan’s batting average, he dismissed the statistic and showed himself to be ahead of his time when it came to Sabermetric philosophy. “Here’s a guy who gets on base an awful lot of times,” Anderson told longtime Cincinnati writer Earl Lawson. “His on-base ratio is unbelievable, like last year—149 hits and 88 walks.” Those numbers, coming in 689 plate appearances, helped Morgan compile a respectable on-base percentage of .351 for the Astros.

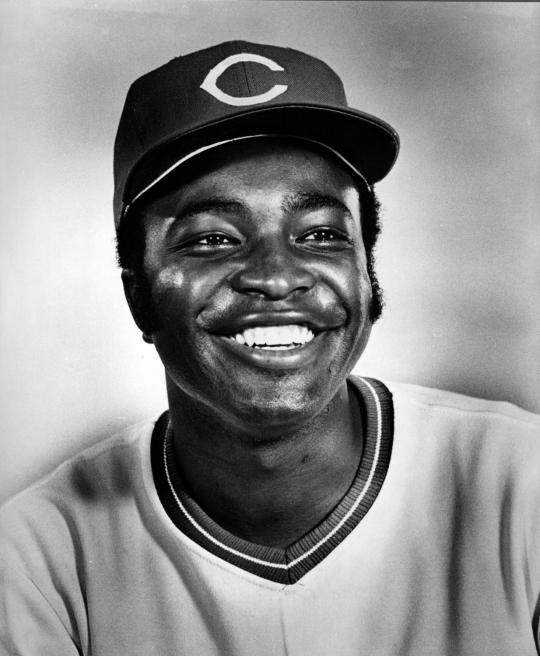

Morgan would blossom in Cincinnati, where he benefited from the presence of better teammates and the wisdom of Anderson. Enjoying a career breakthrough in 1972, Morgan led all National League players with 115 walks and a whopping .417 on-base percentage, helping the Reds win the pennant and advance to a berth in the World Series.

Over the next two years, the man known as “Little Joe” continued to play well but then fully emerged as a superstar in 1975, as he led the Reds to the first of back-to-back world championships. Morgan batted a career-high .327 and leading the league with a .466 on-base percentage on the way to winning the NL’s MVP Award. He repeated as league MVP in 1976, compiling a league-best .576 slugging percentage. How good was Morgan in 1975 and ‘76? He was just about the best player in the game, that’s how good. He was also well on his way to the Hall of Fame.

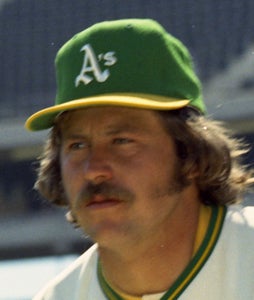

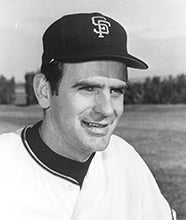

Outside of the Morgan deal, the San Francisco Giants and Cleveland Indians also made a trade that first day of the winter meetings. The Giants sent Gaylord Perry and touted young shortstop Frank Duffy to the Indians for Sam McDowell, a hard-throwing left-hander who seemed to be in his prime. In yet another major exchange, the A’s acquired left-hander Ken Holtzman, already the author of two no-hitters, from the Chicago Cubs for outfielder Rick Monday, who at the time was best known for being the first player taken in the inaugural amateur draft of 1965.

Still, there was more to come. The next day, November 30, the Minnesota Twins dealt veteran shortstop Leo Cardenas to the California Angels for young left-hander Dave LaRoche. In the meantime, the A’s announced the release of a well-liked veteran pitcher, Jim “Mudcat” Grant, a head-scratching move given how effective Grant had been pitching out of the bullpen in 1971.

On December 1 came the news of the release of an even bigger name. The Cubs officially cut loose 40-year-old Ernie Banks, who was already planning to retire, and added him to their coaching staff for the 1972 season.

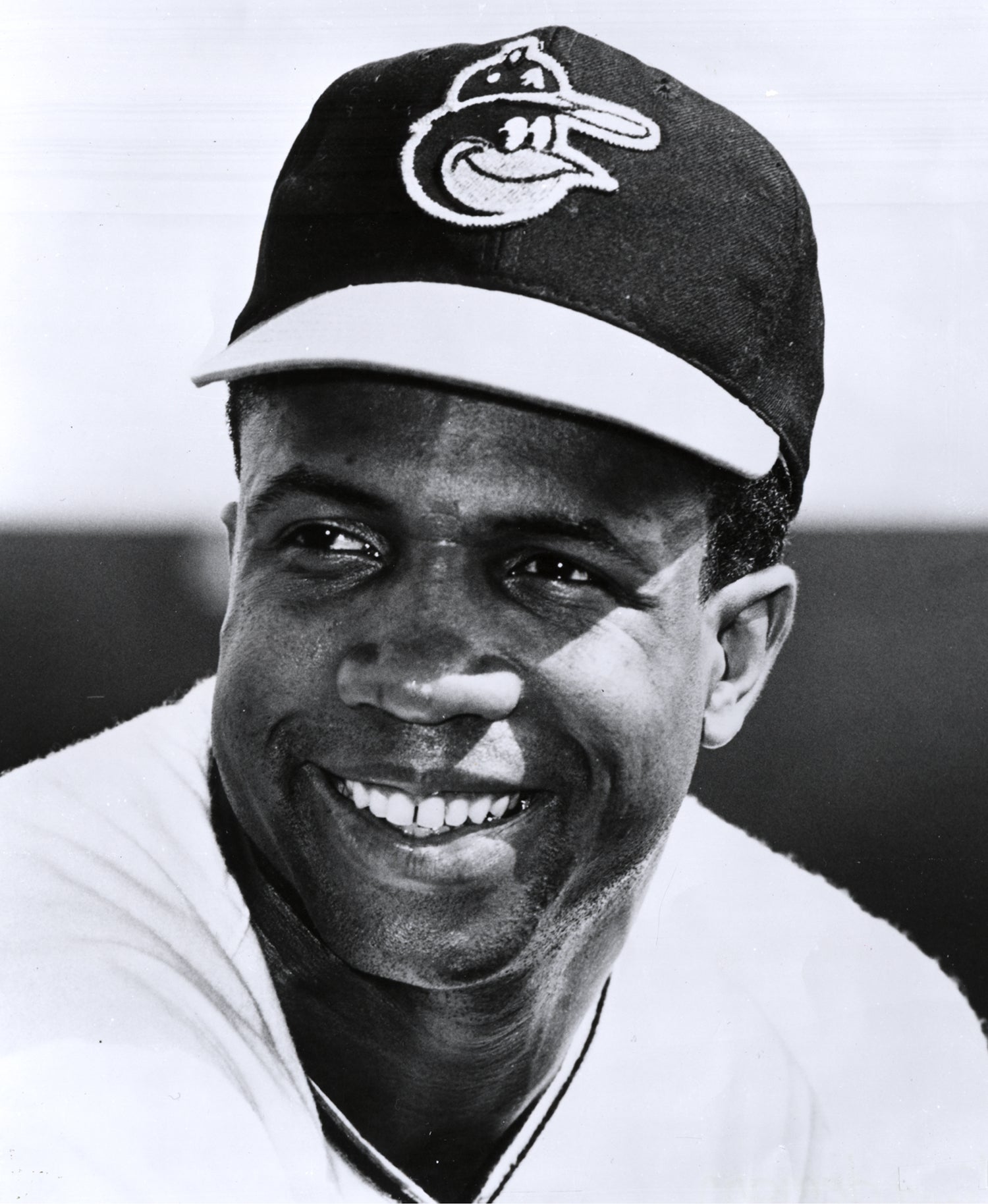

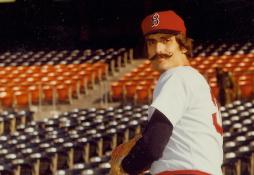

Then came the whirlwind flourish of December 2. That’s when teams engineered eight additional trades, this time involving a total of 30 players. The full day of activity included a three-player deal between the Astros and the Kansas City Royals. The Astros gave up promising first baseman John Mayberry for two young pitchers, Jim York and Lance Clemons. In an even bigger deal, the Orioles traded their veteran star, Frank Robinson, and lefty reliever Pete Richert to the Los Angeles Dodgers for young right-hander Doyle Alexander and three minor leaguers. After acquiring Robinson, the Dodgers sent slugging first baseman Dick Allen to the Chicago White Sox for left-hander Tommy John.

By the time the winter meetings ended on December 3, a day that saw four more trades finalized, major league teams had combined to make a total of 15 trades involving 53 players. The series of blockbuster deals generated headlines in everything from daily newspapers to the cite>Sporting News and Sports Illustrated, keeping baseball’s hot stove churning during the NFL’s regular season. The wave of trades also created a series of aftershocks that changed the game’s landscape for the better part of the next decade.

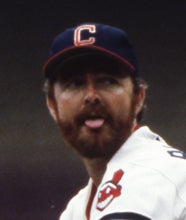

At the time, the Giants’ decision to trade the 33-year-old Perry for the 29-year-old McDowell seemed like a smart deal for their owner/general manager, Horace Stoneham. After all, the Giants were acquiring the younger pitcher and the harder thrower. Unfortunately, the Giants did not realize the full extent of McDowell’s drinking problems, and how they would derail his career. By 1973, McDowell became an ex-Giant. By 1975, he was out baseball.

In the meantime, the durable Perry went on win a league-best 24 games for the Indians in 1972. Two years later, he added 21 wins while winning the American League’s Cy Young Award. Perry would continue to pitch until 1983 (by which time he had won 314 career games), a full eight years after the retirement of McDowell.

Another one of the other superstars involved in the winter swapmeet would also win a major award. White Sox skipper Chuck Tanner told Chicago sportswriter Jerome Holtzman that Allen “ought to help us win at least 20 games with his bat.” Tanner’s words were an exaggeration to be sure, but not by as much as some would have thought. Motivated by the ultimate player’s manager in Tanner, the enormously talented Allen led the league in slugging percentage, RBI and walks in 1972, while carrying the Sox to within five-and-a-half-game of a far more talented team in Oakland. It was Allen’s best season ever—and it would earn him the MVP Award.

By the winter of 1971, the Royals had played three full seasons as an expansion team. Although they were not yet ready for legitimate contention in the Western Division, the addition of Mayberry gave their offense a foundation from which to build. By 1976, when the Royals won the first of three straight division titles, Mayberry had developed into a game-breaking cleanup hitter. With Mayberry, Hall of Famer George Brett, and the underrated duo of Hal McRae and Amos Otis forming the nucleus of the Royals’ offense, Kansas City was now a major force.

Other trades played even larger roles in affecting outcomes in upcoming pennant races. Few would benefit from the Winter Meetings as much as the game’s developing dynasty, the one taking shape in the Bay Area. Acting as his own general manager, Oakland owner Charlie Finley managed to get Holtzman from Cubs GM John Holland. The addition of Holtzman gave the A’s a third top-flight starter to supplement Jim “Catfish” Hunter and Vida Blue.

Thanks to the addition of Holtzman, the A’s became a more formidable foe, particularly in the postseason. From 1972 to 1974, Holtzman won four of five World Series decisions while posting an ERA of 2.55. He pitched even more effectively in the Championship Series, where his ERA of 1.55 sparkled. Without Holtzman’s postseason pitching, not to mention his average of nearly 20 wins and 250 innings during the regular seasons over that same span, the A’s might not have won three consecutive World Series.

Other than Houston’s loss of Morgan, no trade had more of a negative impact than the Orioles’ decision to trade Frank Robinson, one of their best all-round players and arguably their most forceful presence in the clubhouse, where “The Judge” ruled Baltimore’s famed “Kangaroo Kourt.” The Orioles thought they could replace Robby with Merv Rettenmund—a .318 hitter in 1971—but he disappointed as an everyday player, while fellow outfielders Paul Blair and Don Buford slumped considerably, causing the pennant winners to fall to third place in 1972.

It’s natural to wonder if we will ever see a winter meeting trading frenzy like we did in 1971, when those 53 players switched teams. Well, it has happened once, back in 1980, when major league teams combined to swap 71 players—the all-time record. Hall of Famer Whitey Herzog, who doubled as both general manager and manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, accounted for much of the activity himself, swinging four trades involving 23 players. Among the players to exchange teams at the ’80 meetings were Hall of Famers Bert Blyleven, Rollie Fingers, and Bruce Sutter.

It’s not likely that we will ever see a repeat of what we saw in either 1971 or 1980, though major league teams did create some buzz at the 2014 winter meetings, when they congregated to make 12 trades involving 37 players. Based on sheer volume, what happened in 1971 and 1980 is not likely to happen again, not with the current dominance of free agency, expensive multi-year contracts, and various no-trade clauses.

Those 1971 winter meetings, when future Hall of Famers Morgan, Perry and Robinson all traded in their old uniforms for new ones, will remain right near the top of the list.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame