“I know a lot of people claim I haven’t lived up to my potential, but that’s hogwash. Nobody can live up to their potential not playing regularly, and I haven’t played regularly since I got into the big leagues.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Willie Crawford

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Willie Crawford

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

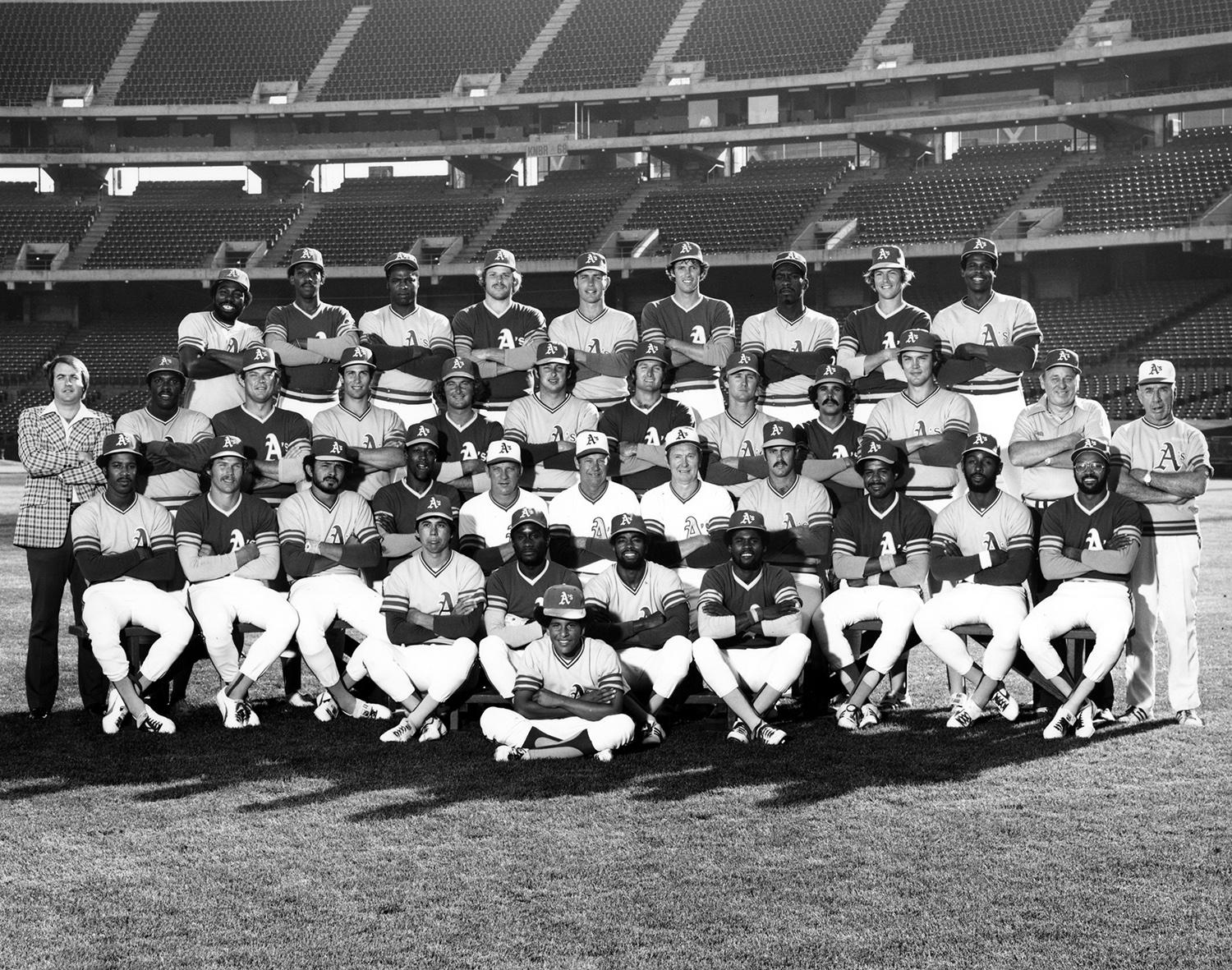

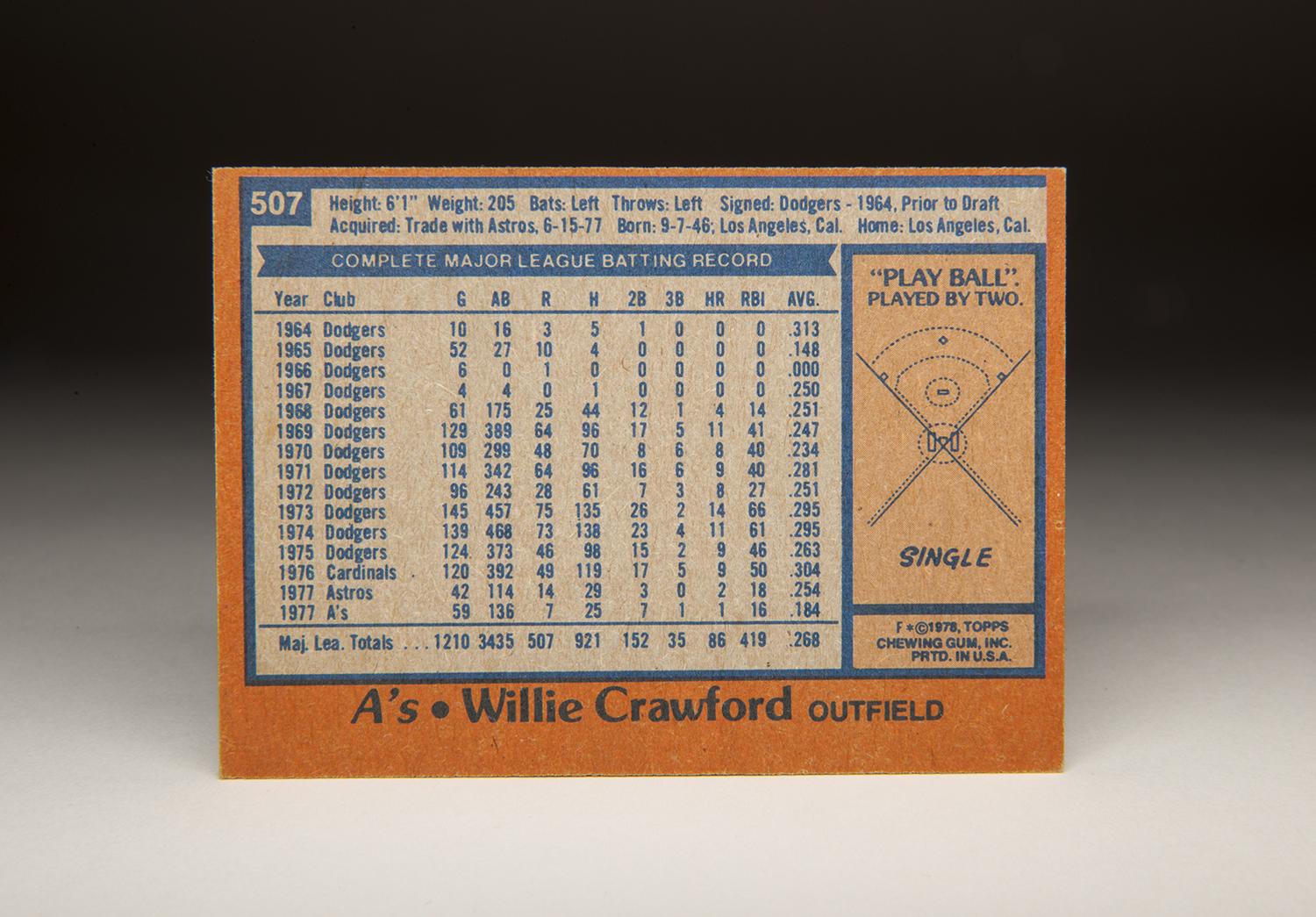

During the spring of 2004, I started work on a research project about outfielder Willie Crawford. Motivated by Crawford’s unusual decision to wear No. 99 for the Oakland A’s in 1977, I wanted to learn more about this once-promising star who never quite fulfilled the predictions of greatness made for him.

I thought about writing Crawford a letter to ask him about his choice of uniform numbers and gather his thoughts about colorful owner Charlie Finley, but never got around to doing it. Sadly, there would be no chance to write that letter; in August of 2004, Crawford died from kidney disease. My procrastination in writing to Crawford cost me the chance to learn more – in a direct way – about this interesting outfielder, but it also motivated me to write something more substantial about his career.

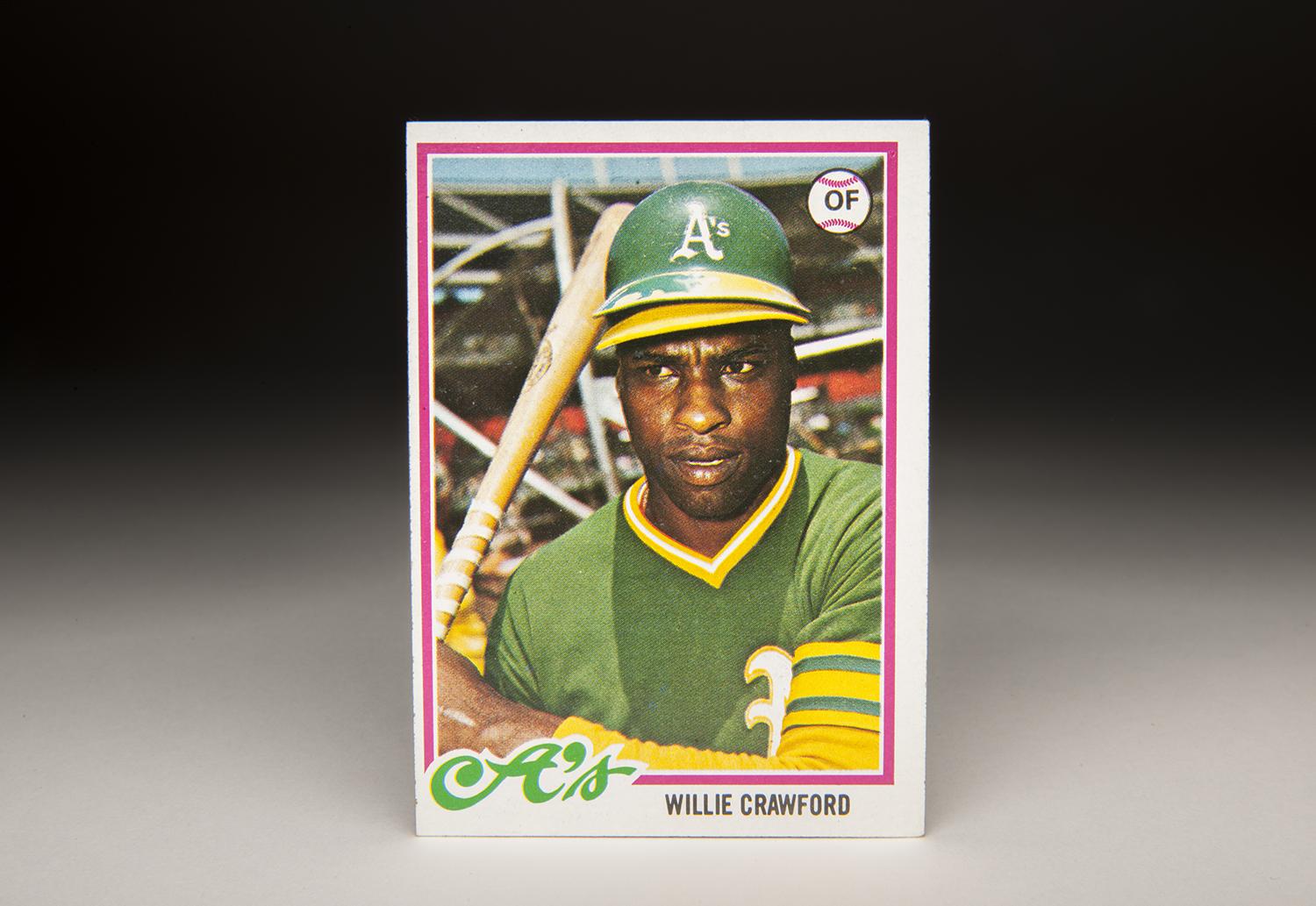

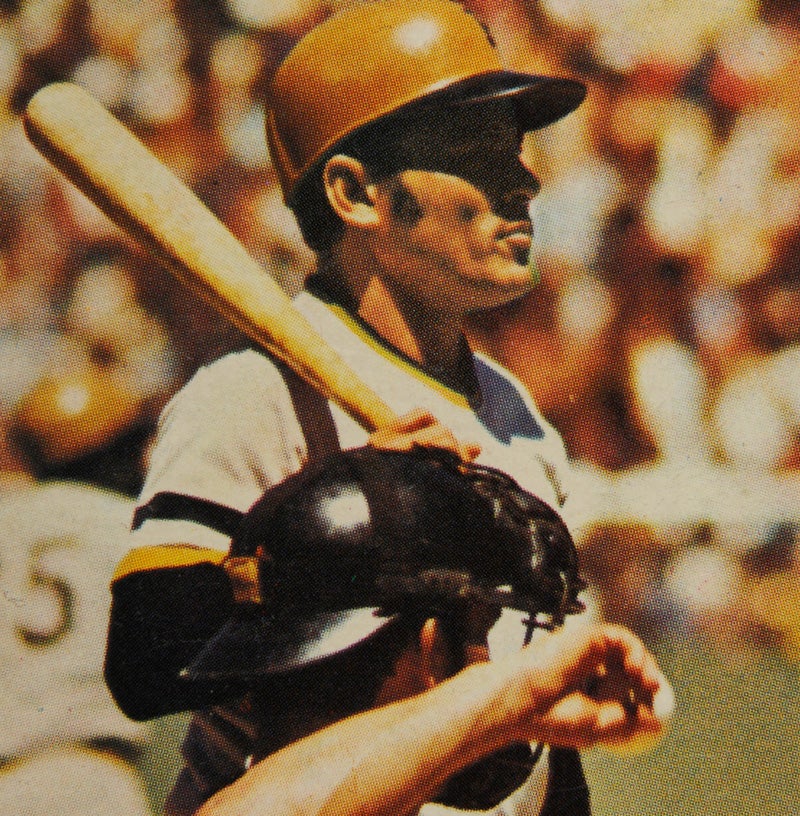

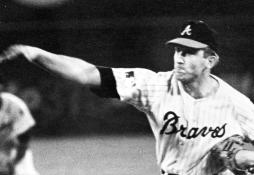

When I think of Crawford, I tend to think of his final Topps card, issued in 1978. It’s the only card that shows him wearing the colors of the A’s, the team that originally tried to sign him in 1964 – only to be beaten to the punch by the Los Angeles Dodgers. We cannot see the No. 99 that Crawford is wearing on the back of his jersey, but Oakland’s gaudy green uniform is in full view. I loved those green-topped jerseys; to me any player wearing that jersey looked better, more athletic. There was just something about those green-and-gold uniforms that made the A’s look cool. Perhaps it was because I remembered the great A’s teams of the early 1970s, teams that dominated the major leagues in winning a trio of world championships.

By the late 1970s, those A’s teams were no longer laying waste to the American League countryside. They were now among the worst teams in either league. But they still had some interesting characters, including a number of prominent past-their-prime players like Earl Williams, Dick Allen and Dock Ellis. One of those players was Crawford.

A couple of other features stand out about Crawford’s 1978 card. Notice how he is wearing his cap underneath his helmet, which is awkwardly perched on top of his head. That is something you almost never see from today’s players (in part because of the prevalence of ear-flapped helmets) but back in Crawford’s day, a number of players sported caps under their helmets. It was a 1970s kind of thing to do. Roberto Clemente and Al Oliver were two of the most prominent. Another one was Willie Davis. Bobby Murcer liked to wear the cap and helmet, as did Manny Sanguillen and Rennie Stennett.

As I remember, those players would wear both the cap and the helmet during their at-bats, but once they would reach first base, they would ditch the helmet, leaving themselves with just the cap. Back then, players were allowed to wear only their caps while running the bases. Today’s rules mandate that players must wear helmets on the basepaths.

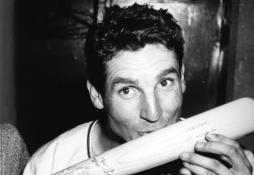

Crawford also had a distinctive way of taping his bats. Just take a look at the bat he is holding in this photo. Rather than tape the handle of the bat completely, Crawford used an alternating pattern, leaving parts of the handle open, and other parts covered with the tape. I must confess as to having no idea what the benefit of such a grip could be, but it does look rather artistic and distinctive.

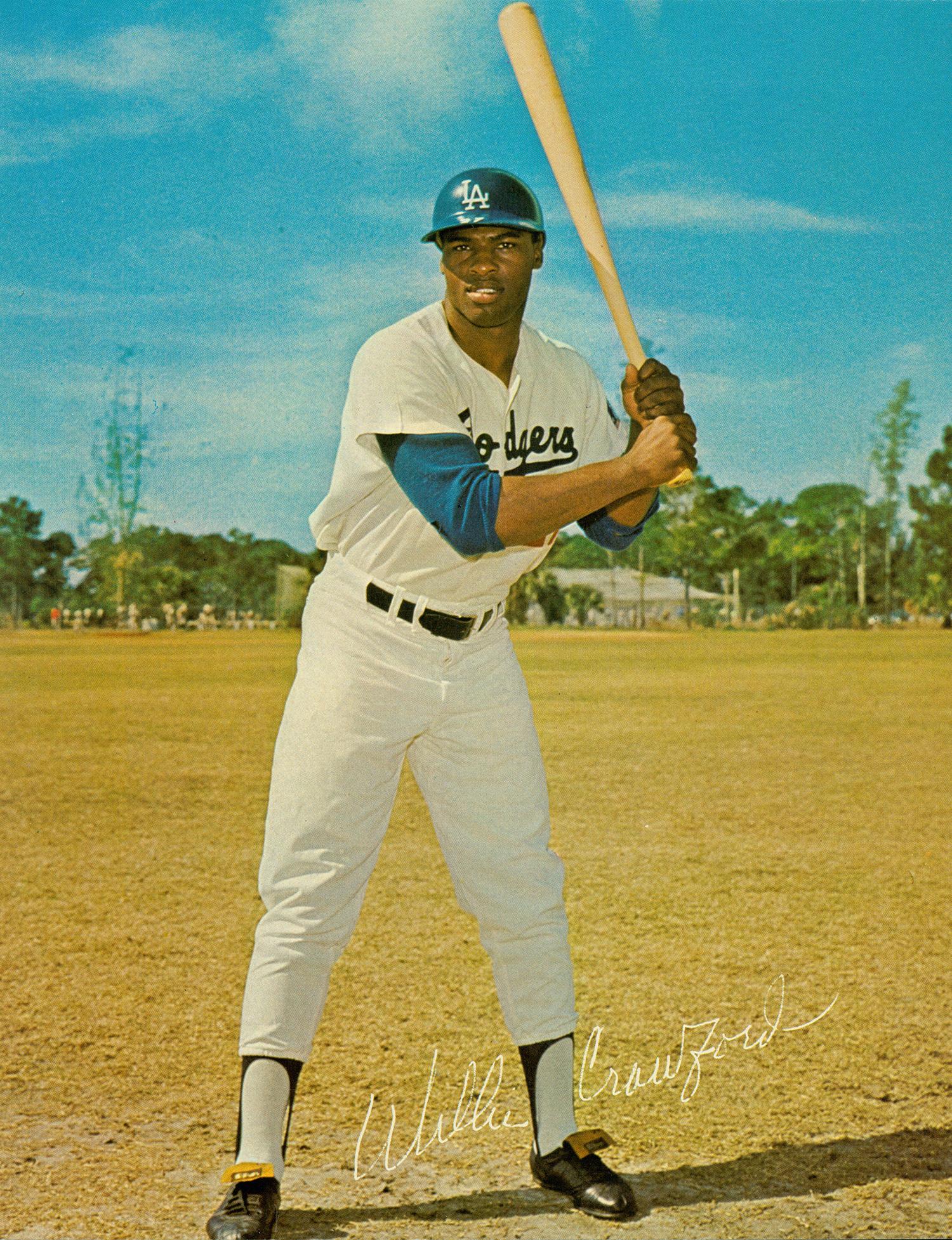

Crawford’s career was more than a little distinctive. At one time, he was the most hotly desired amateur player in the land. In 1964, the 17-year-old Crawford played his final season at Fremont (Calif.) High School, where he starred for head coach Phil Pote, his mentor and a future major league scout who would eventually appear in Moneyball. Crawford drew the interest of almost every one of the 20 major league teams at the time. Keep in mind that a major league draft had not yet been instituted, so Crawford was essentially a free agent, able to sign with the highest bidder. With his combination of power, speed, and throwing arm, a number of teams (including the Dodgers, Kansas City A’s, and New York Yankees) envisioned him as a centerpiece to their outfield. By the end of the bidding war, 16 teams had made formal offers to Crawford.

Dodgers director of scouting Al Campanis filed a scouting report that said Crawford “hits with the power of Roberto Clemente and Tommy Davis at a similar age.” Kansas City owner Charlie Finley lifted the level of praise even further, calling Crawford “a Willie Mays with the speed of Willie Davis.” In other words, Finley felt that Crawford had the hitting and fielding potential of a Hall of Famer (Mays) and the speed of the fastest man in the game (Davis). High praise indeed.

Finley liked Crawford so much that he visited their family home and gave the youngster a signed, framed portrait of himself, which eventually hung in their living room. More to the point, Finley offered Crawford a bonus of $200,000 to sign with the A’s and play center field. It was the largest bonus ever offered to an African-American player coming out of high school or college. For his part, Crawford seemed genuinely intrigued by the advances of Finley, referring to him as “one of the nicest millionaires I know.”

Crawford considered the offer, but ultimately turned down Finley. Instead, he signed a contract that included a bonus of $100,000 (roughly half the sum of Finley’s offer) with the Dodgers. Even though he took less money, it was still a financial boon for Crawford, who had grown up in poverty in the Watts section of Los Angeles. Signing with the Dodgers also allowed him to remain on the California coast, where he felt more comfortable than in a place like Kansas City, where he had never been. He also found himself swayed by Dodgers scout Tommy Lasorda, who had taken the time to attend the funeral of Crawford’s grandfather.

The Dodgers, like all of the teams involved in the bidding, expected Crawford to become a superstar. But they decided to start him out in the lower minors in 1964, before rewarding him with a late-season call-up to Los Angeles. Crawford was still only 18, but he batted .313 in 17 plate appearances with the Dodgers.

Over the next three seasons, Crawford split time between the minor leagues and the Dodgers, but he failed to gain traction at the major league level. He collected only 31 at-bats during that span, not enough to show what he could do. Still, the Dodgers liked him enough to include him on their roster throughout the 1965 season, including the World Series. Used as a pinch-hitter, Crawford went 1-for-2 against the Twins and earned his first World Series ring.

It was not until the 1968 season that Crawford received a significant amount of playing time in Los Angeles. The circumstances weren’t easy – it was the Year of the Pitcher – and Crawford batted .251 with only four home runs as a utility outfielder. Crawford made the mistake of trying to hit home runs, rather than simply trying to make hard contact. The approach did not work.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

A more regular role came Crawford’s way in 1969. He became a platoon partner of Manny Mota in left field and showed some power, hitting 11 home runs in 389 at-bats. Still only 22, Crawford showed the Dodgers enough to make him part of a right field platoon in 1970. His hitting regressed that season, however, as his batting average fell off to .234 and his power production dropped to eight home runs. At one time considered a sure superstar in the making, Crawford now had the Dodgers wondering exactly what they had.

Crawford played better in 1971. Moving back to left field, he hit .281 and raised his OPS to .776. Then came a fallback in 1972. Crawford’s home run output and OPS numbers declined, frustrating the Dodgers once again.

Crawford entered the 1973 season at the crossroads. He was now 26, too old to be considered a prospect anymore and no longer a player with the potential of stardom. To the Dodgers’ surprise, he put up his best season. Crawford credited to the breakout to his decision to play winter ball, where his manager, Frank Robinson, worked with him on his approach to hitting. Robinson told him to stop trying to hit home runs, and instead focus on putting line drives into play. The new approach worked. As the Dodgers’ semi-regular right fielder, Crawford hit .295 with 78 walks and 14 home runs. His OPS of .849 was by far the best of his career.

During that 1973 season, Crawford sat for a long interview with Black Sports Magazine. He discussed his frustration with the Dodgers, specifically their unwillingness to use him in anything other than a platoon role. “You know, from a statistical and monetary point of view, my career has been sort of a disappointment,” Crawford told writer Kenneth Bentley. “I know a lot of people claim I haven’t lived up to my potential, but that’s hogwash. Nobody can live up to their potential not playing regularly, and I haven’t played regularly since I got into the big leagues.”

Regular playing time eluded him again in 1974, but Crawford delivered another good season. Crawford again hit .295, this time with 11 home runs, as he platooned with strong-armed Joe Ferguson in right field. He also contributed to a pennant-winning season in LA, as the Dodgers advanced to the World Series for the first time since 1966. Appearing in his second Series, Crawford again did well, picking up two hits in six at-bats against the world champion A’s.

The 1973 and ’74 seasons turned out to be the apex of Crawford’s career. His hitting tailed off significantly in 1975. The following spring, the Dodgers traded their onetime phenom, sending him to the St. Louis Cardinals for second baseman Ted Sizemore.

Crawford spent a solid season in St. Louis, where hit .301 with nine home runs. He played well as a platoon right fielder, but the Cardinals needed pitching. So in October, the Redbirds dealt him, left-hander John Curtis, and infielder Vic Harris to San Francisco for a package headlined by pitchers Mike Caldwell and John D’Acquisto.

Crawford did not even last all of Spring Training with the Giants, who had Darrell Evans playing left field and Jack Clark in right. Rather than use Crawford as a backup, the Giants made a puzzling deal, sending him to the Houston Astros for a light-hitting second baseman named Rob Andrews. Then, after two unproductive months with the Astros, Crawford moved on again, after telling the team that he wanted to test the free agent waters at season’s end. Rather than lose him for nothing, the Astros traded him to the A’s for corner infielder Denny Walling.

After failing to sign Crawford in 1964, Finley finally had his man – some 13 years later. Unfortunately, the move to the A’s left both the owner and the player dissatisfied. The most memorable moment of Crawford’s tenure in Oakland was his decision to wear No. 99. Other than that, not much of note happened. Crawford hit a measly .184 in a half-season, looking little like the talent that Finley had once compared to Mays. Crawford didn’t like playing for the A’s, either; they were a miserable team, heading for a 98-loss season. “It was depressing,” Crawford told the Sporting News. “They went with the kids. I was just a spectator up there.”

Perhaps that explains why Crawford looks so unprepared in his final Topps card. With his helmet off-kilter atop his cap and his bat held in such an unusual pose, Crawford appears a bit off-balance. That’s just how his days in Oakland must have felt.

As for his relationship with Finley, the man he had once called the “friendliest millionaire” he ever met, Crawford was able to offer little insight. “I didn’t have any communication with the man,” Crawford said bluntly and with a bit of sadness. Crawford’s tenure with the A’s represented his final major league stop. After a failed Spring Training comeback with the Dodgers, he would continue his career in the Mexican League, but would never again return to the major league stage. At the age of 30, Crawford had played his final game in the big leagues.

So what happened? How exactly was it that this phenom, who was considered “can’t-miss,” did miss? There were several problems. Crawford’s outfield play, crude and somewhat clumsy, left much to be desired. Crawford also struggled to hit left-handed pitching, so much so that the Dodgers cast him in the role of a platoon player. Frustrated by a lack of consistent playing time, Crawford struggled with his weight – and with alcohol.

Allowing his problems to fester, Crawford didn’t tackle the latter obstacle until well after his playing days. One night, he was drinking from a bottle of vodka while listening to a sermon by Billy Graham. Something clicked at that moment of desperation; he called up Al Campanis, asking him for help. Campanis reached out to two former Dodgers, Lou Johnson and Don Newcombe, who had also struggled with alcoholism before receiving the help that they needed. Johnson and Newcombe convinced Crawford to start attending meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Crawford did just that, but he still felt he needed more. He checked himself into The Meadows, a renowned clinic that specialized in helping alcoholics. With help from The Meadows, Crawford stopped drinking.

Crawford found peace in that area of his life, but another problem would eventually develop. He was stricken with kidney disease, which left him debilitated. After a struggle of several years, he succumbed to the disease in 2004. He was just 57.

Crawford’s life was too short, but it was a good life, nonetheless. By all accounts, he was a popular and well-liked teammate. After each season, he went home to his old neighborhood in Watts and conducted free baseball clinics for kids with no money. And he did find a way to overcome his addiction to alcohol, making his life better after his playing days had ended.

I never got that chance to communicate with Willie Crawford, but my research turned up something just as important – a good man.

Thanks to Bill Francis and Tom Shieber of the Hall of Fame for their research assistance with this article

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame