- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

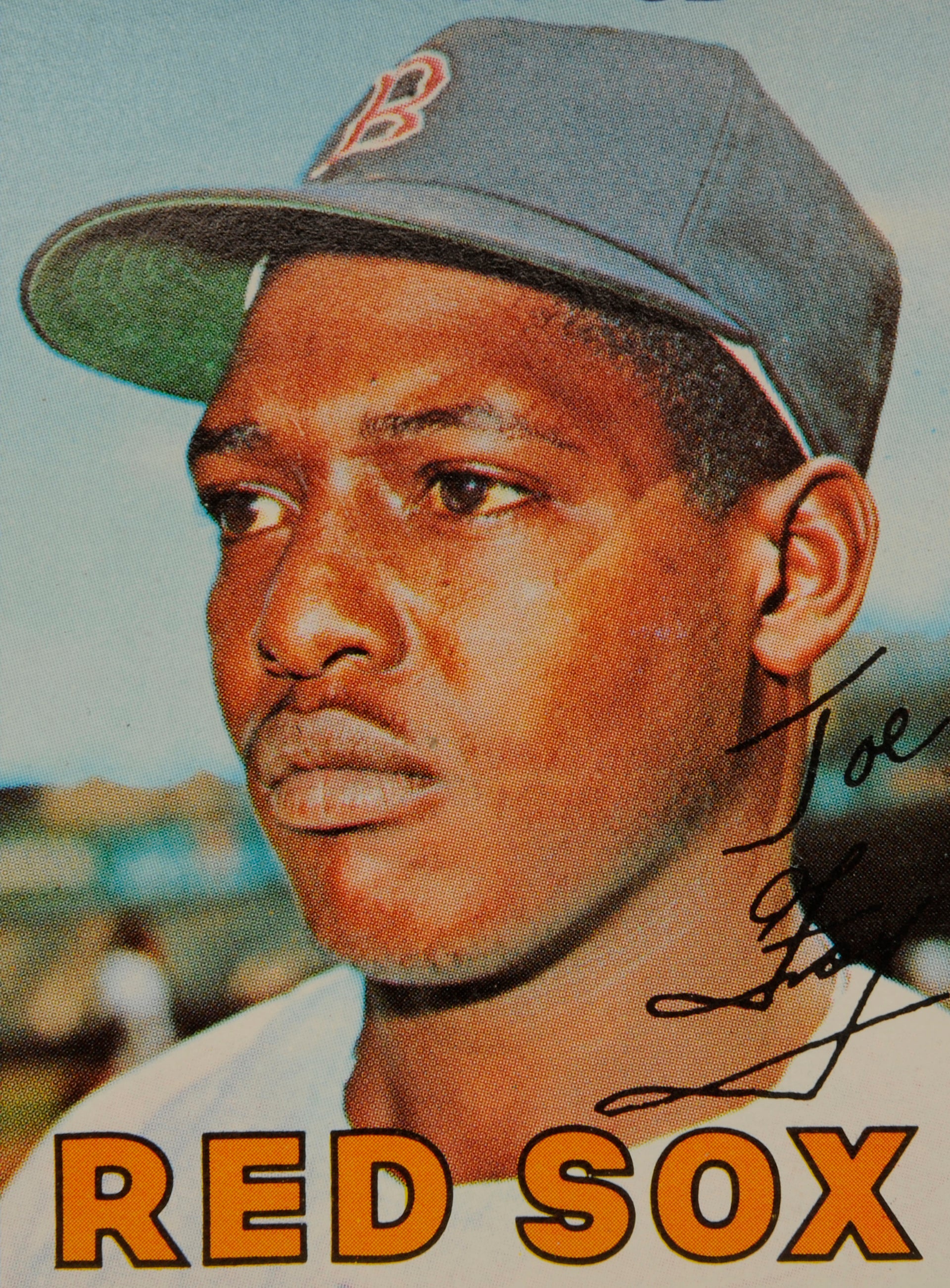

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

The 1969 Topps set has taken its share of criticism over the years. That was the season that Topps had to resort to using old and outdated photographs, some from two or three years earlier, because players refused to pose for new ones; they were unhappy with the compensation they were receiving from the card company. That’s why we see so many players pictured without caps, or wearing uniforms that don’t match up with their listed teams.

In spite of that, I like the 1969 set. The photography is pretty solid throughout all of the series. There are lots of clear close-ups of players, done both in portrait and profile style. I also enjoy the design of the cards. It’s simple and clean. The name of the team appears in an attractive font at the bottom, while a colored circle near the top features the player’s name and position. The design is balanced and unobtrusive, allowing the photography to occupy the vast majority of the white space on the front of the card.

The 1969 card of Elrod Hendricks provides us with a special curiosity. For most of his career, he was known as either “Elrod” or “Ellie.” I cannot recall - not even once - a broadcaster or writer referring to him as “Rod.” Yet that is the name that appears on the front of the card: “Rod Hendricks.” As a young player coming off his rookie season, Hendricks was not yet a household name in 1969. Perhaps someone just assumed that Rod was his name. Or maybe he wanted to be called Rod, only to change his mind later in his career. Or maybe the design person at Topps simply didn’t know. I guess we can be thankful that no one called him “E-Rod.”

In 1970, Topps realized the error and changed his name to read “Elrod Hendricks.” It remained that way in 1971. By 1972, Topps was using the less formalized name of Ellie. In 1973, Topps did not put out a Hendricks card, but returned him to the fold in 1974. He would remain Ellie on his Topps cards for the rest of his career.

I was lucky enough to meet Elrod Hendricks once. It was back in the spring of 1996. We were conducting video interviews for the Hall of Fame’s archive - and Hendricks was more than happy to accommodate our request. With the Orioles preparing to play the Yankees at their new Spring Training facility in Tampa, FL, Hendricks was in his usual location: On the playing field, where he loved to be whenever possible.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

I found Hendricks, who would talk to anyone, to be as approachable as anyone. I started asking him about his favorite memories, including World Series moments. I also asked him about playing in the 1971 Series against Roberto Clemente, who carried Pittsburgh to victory in seven games. Hendricks had the utmost respect for Clemente. I also remember Hendricks smiling throughout the interview. He was affable throughout, doing his best to provide some good insights for the Museum's archive.

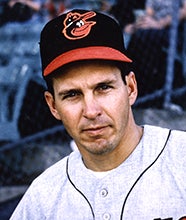

While star players often become the faces of franchises, sometimes journeyman ballplayers became synonymous with a team through hard work, longevity, a community-minded spirit, and a general amicability. Hendricks embodied all of those qualities, making him as recognizable to diehard fans of the Baltimore Orioles as Hall of Famers like Cal Ripken Jr. or Brooks Robinson. In many ways, Hendricks was the Orioles. His Orioles career spanned from 1968 until 2005, when he worked with the organization as a coach. If not for brief layovers with the Chicago Cubs in 1972 and the New York Yankees in 1976 and ‘77, Hendricks would have been associated continuously with the Orioles for 38 consecutive seasons.

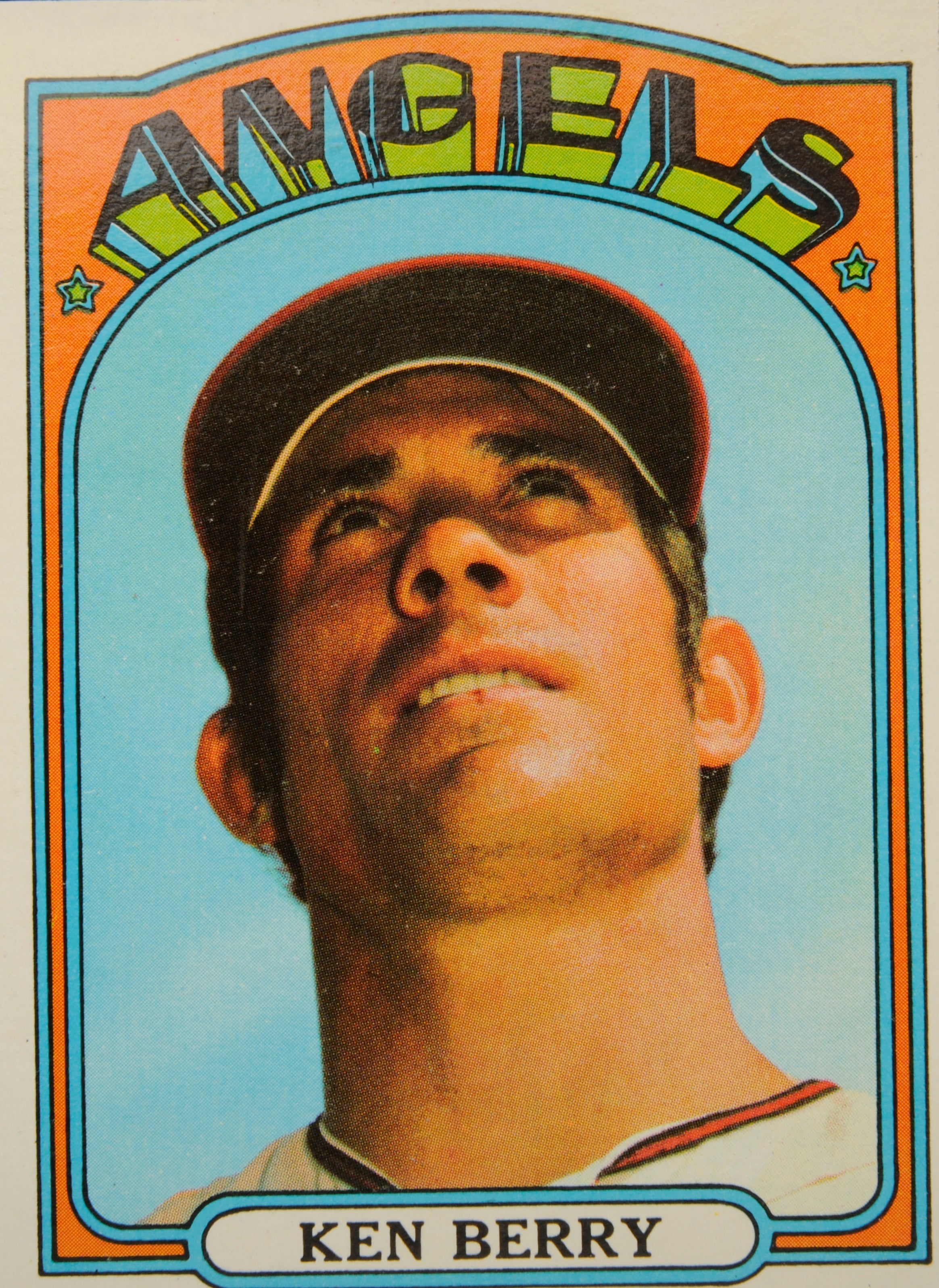

As much as we remember Hendricks for his days with the Orioles, they were not his first organization. Hendricks signed with the old Milwaukee Braves in 1959, but lasted only two seasons in their farm system before being released. He then signed with the St. Louis Cardinals, spending a season and a half in their minor league chain before drawing another release. He sought refuge in the Mexican League, signing with Jalisco. He became a legendary figure in Mexico, particularly after he hit 41 home runs and batted .316 one season. At some point in August of 1966, Jalisco decided to cash in on Hendricks and sold his contract to the California Angels. After finishing out 1966, he played another season in the Angels’ system. When the Angels chose not to protect him in the Rule 5 draft, the Orioles claimed him, having scouted him in the Puerto Rican Winter League. The O’s brought him to the major leagues in 1968, ending his decade-long apprenticeship in the minor leagues.

Hendricks’ perseverance paid off, since the rules dictated that the Orioles had to keep him on their roster for all of 1968. They used him as a platoon catcher, alternating him with Andy Etchebarren. He hit only .202 in 79 games, but played so well defensively and had such a likeable personality that he drew favor from manager Earl Weaver and became a keeper in Baltimore.

Hendricks would never become a star, but he was one of those wonderful platoon players whom Weaver groomed and used so effectively during the Orioles’ championship run from 1969 to 1971. The peak of his career came in the 1970 World Series, when he hit .364 and belted a home run in a five-game victory over the Cincinnati Reds.

As a left-handed hitting catcher, Hendricks alternated with Etchebarren, giving the Orioles an occasional home run and a catcher capable of forging a good rapport with his talented pitching staff. He was particularly mobile behind the plate, a trait that allowed him to scramble and block pitches that might have eluded other catchers.

Hendricks didn’t look like your typical catcher. Built lean at 6-foot-1 and 175 pounds, he featured the wiry frame of a rangy shortstop or a lightning-quick center fielder. He was also a catcher at a time when few black or Latino players were given the chance to play behind the plate. Not surprisingly, elite fielding catchers like Hendricks and Manny Sanguillen shined once they got an opportunity.

Remaining with the O’s until midway through the 1972 season, Hendricks became expendable because of the emergence of another young left-handed hitting catcher, Johnny Oates. Now doubled up at the position, the Orioles traded Hendricks to the Cubs for veteran outfielder Tommy Davis. Given the wear and tear on the overworked Randy Hundley, the Cubs needed help at catcher, but Hendricks’ stint in Chicago turned into a near disaster. He batted only .116 in 56 at-bats. The reason? Hendricks had a calcium deposit in his neck, a condition that caused him partial paralysis in his right hand and arm. It was hard enough for Hendricks to hold his car keys, let alone control a large wooden bat.

Disillusioned with his poor play, the Cubs traded Hendricks that winter. They sent him right back to the Orioles, settling for minor league catcher Frank Estrada as the trade compensation. Having dealt Oates over the winter, the Orioles now needed a left-handed hitting catcher to back up the newly acquired Earl Williams. It was a role for which Hendricks, a strong defender, was perfectly suited. It also didn’t hurt that Hendricks spoke both English and Spanish, a bilingual ability that allowed him to better communicate with left-handed ace Mike Cuellar.

Hendricks remained in the backup position until the trading deadline in 1976, when the Orioles sent him to New York as part of the massive deal that brought Rick Dempsey and Scott McGregor to the Orioles. Hendricks became a backup catcher with the Yankees, playing behind the durable and talented Thurman Munson. As a left-handed hitter and strong character guy in the clubhouse, Hendricks seemed like a perfect fit as a backup catcher in the Bronx. But he spent most of the season at Triple-A Syracuse. Perhaps that explains why the Yankees let him go after the season, allowing him to return to Baltimore for a third time. He became a player/coach for the O’s in 1978 and then appeared in one final game in 1979 before ending his playing career.

Hendricks turned to coaching full-time. As the Orioles’ bullpen coach, he worked under a host of managers, during a run of years that spanned from 1978 to 2005. Along the way, he survived a bout with testicular cancer and a stroke, but he kept coaching. After the 2005 season, the Orioles reassigned him because of concerns over his health. On December 21 of that year, he suffered a massive heart attack that took his life. He was just one day short of his 65th birthday.

Hendricks’ career statistics are hardly overwhelming, but for fans of baseball in the 1970s, his value exceeded the numbers. As Hall of Fame right-hander Jim Palmer said of Ellie in a 2001 interview: “He was the perfect receiver. If I told him to sit on the corner, he sat on the corner. If I got the ball there on time, he could throw the runner out. He caught my no-hitter [in 1969]. I had the utmost confidence in him.”

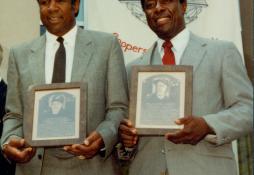

Additionally, Hendricks might be the best player that the Virgin Islands have ever produced. Remarkably, the native of St. Thomas did not start playing the game until he was 13, and only after his insteps had been crushed by the wheels of a truck. But he managed to come back from the injury, learn the game, and eventually catch the attention of Hank Aaron, who was visiting the Virgin Islands during a wintertime stopover. Aaron recommended to Braves scouts that they sign Hendricks. The Braves did just that.

Most importantly, Ellie was one of baseball’s good people. Encouraging, upbeat, and always willing to give back to the game, Hendricks made a positive impression on just about everyone whom he never met. Thankfully, I was one of those people. For that - and many other reasons that Orioles fans surely understand - the game badly misses a guy like Ellie Hendricks.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame