- Home

- Our Stories

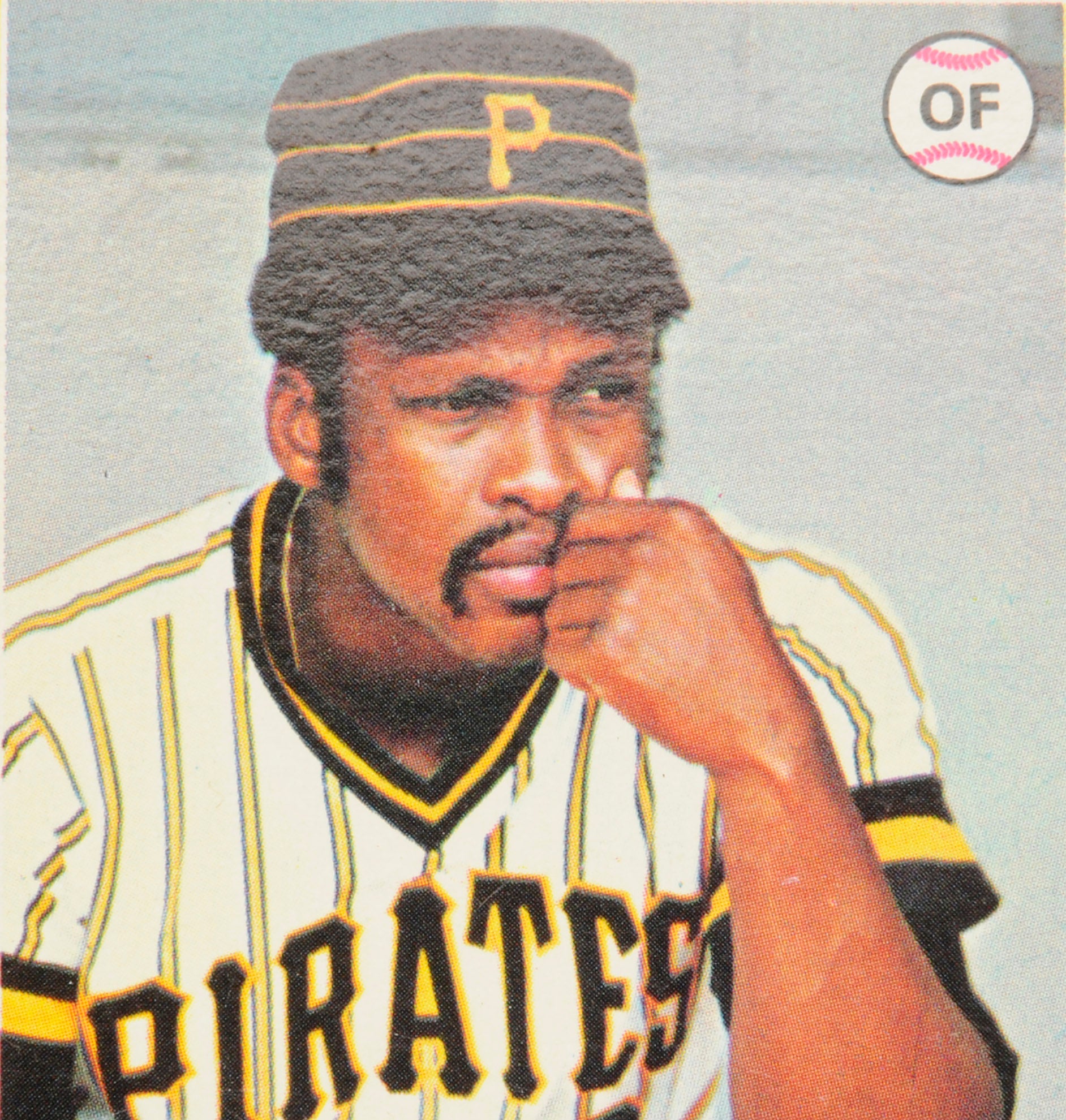

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps Willie Stargell

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Willie Stargell

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

When you try to put together a set of cards by picking up random packs at your local drug store, you’re bound to run into roadblocks. For me, one of those years was 1974. I aggressively bought a new pack of cards every Saturday at the shops in my hometown, but I just couldn’t find the one card that I really wanted: Willie Stargell’s Topps card. I’m not sure why I became so infatuated with the 1974 card; I actually liked the 1973 card a lot more, since it was an action shot, showing Stargell stretching to receive a throw at first base ahead of the arrival of Del Unser. I also preferred the 1973 card of Bobby Bonds, which features an unexpected cameo appearance by Stargell, who is attempting to retire Bonds in a rundown play.

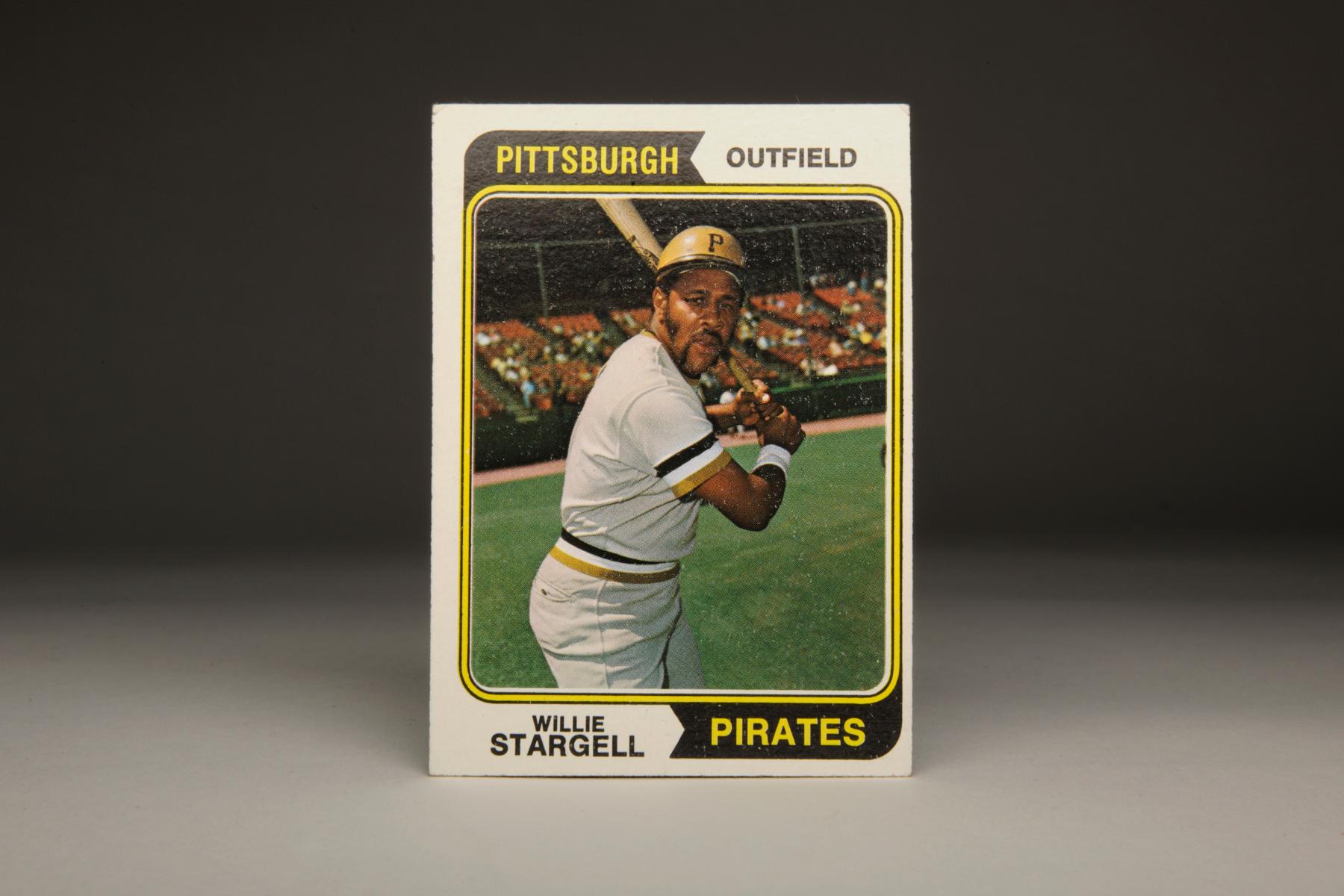

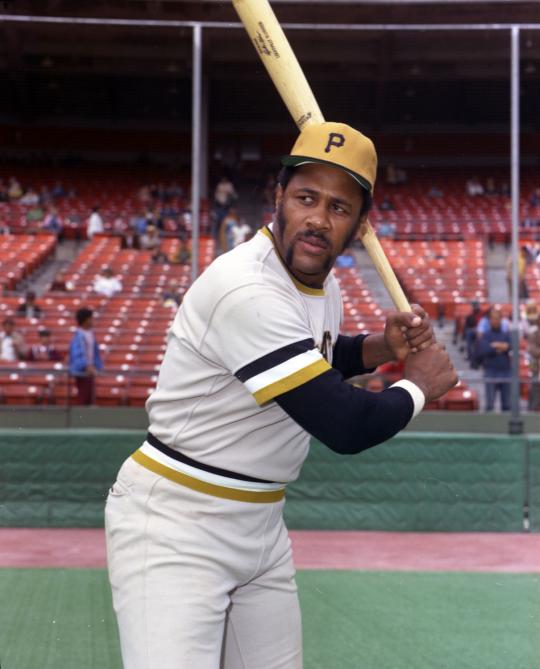

By comparison, the 1974 Stargell looks rather ordinary. It’s a good card, but it lacks any quirks or curiosities. We see Stargell, clearly posing before a Pittsburgh Pirates road game, holding a bat in the ready position. It’s one of many kinds of posed shots that Topps used in the days when action shots were still relatively rare.

None of that really mattered to me in the spring of 1974. I liked and admired Willie Stargell so much that I just had to have this card. It became my Holy Grail, my White Whale, that summer. When I couldn’t find it in stores, I became motivated to do something foolish. I decided to take, without permission, this elusive 1974 baseball card from my next door neighbor’s house.

Before anyone decides to contact the authorities about this case of theft, let’s remember that I was all of nine years old at the time. Let’s also note that justice was served, and quickly. My neighbor Hank Taylor - the older brother of one of my best friends, Alec - knew about my infatuation with the Pirates’ slugger. He knew that I had taken the Stargell card from his desk. Within a day of the theft, Hank quickly and rightfully confronted me about the card. Feeling humiliated at being caught and guilty over what I had done, I admitted to the crime and returned the pilfered item that day. As I look back at this incident all these years later, I’m tempted to make the following conclusion: Through Hank Taylor, Willie Stargell taught me an important lesson about how wrong it was to take something that didn’t belong to me.

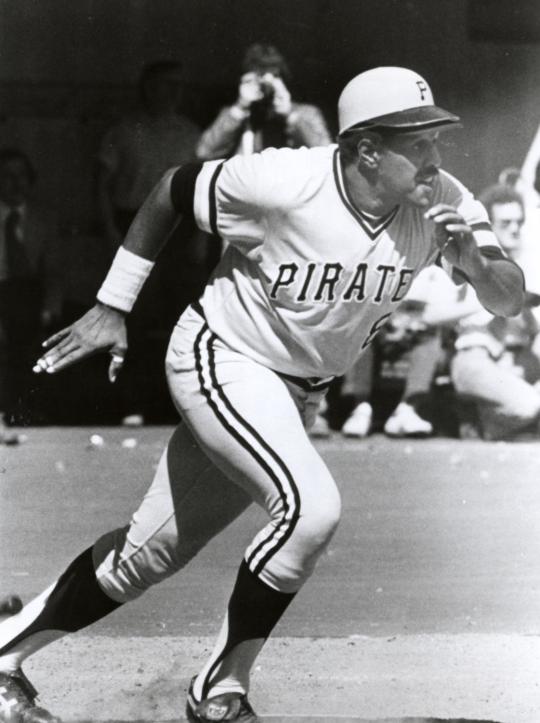

So why exactly did I like Stargell so much back in the day? My friends and I grew up in Westchester County, mostly as fans of the New York Mets or New York Yankees, with some Philadelphia Phillies fans mixed in for good measure. We used to imitate hitters for the home team, like Roy White’s pigeon-toed stance with the Yankees, or Felix Millan’s choked-up hold with the Mets. We also tried imitating players for other teams. One of them was Joe Morgan, who regularly flapped his left elbow like a chicken wing as he waited for the next pitch to be delivered. The other was Stargell, because of the unusual way that he “windmilled” his bat in a rhythmic circle. As he awaited each pitch, Stargell rocked back and forth in the batter’s box, motioning his bat forward, pointing it for a moment toward center field, and then bringing the bat backward for another swirl. The windmilling seemed to help Stargell’s timing. It might have even helped his power, in the way that those old-fashioned pitching windups seems to add extra mileage to pitchers’ fastballs. Either way, it couldn’t have been much fun for National League hurlers having to watch Stargell rev himself up for his next ferocious swing.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

We knew about Stargell’s batting stance, his prodigious power, and his reputation as one of baseball’s good guys. But we didn’t know the whole story. Given our youth, we didn’t understand that Starg had grown up poor, in contrast to our comfortable upbringing.

For much of his youth, Stargell lived in a governmental project in Alameda, Calif. There Stargell and his family lived under meager circumstances, but he encountered relatively little racism in the integrated Bay Area community. Those circumstances began to change in 1959, when he signed his first professional contract with the Pirates and reported to the team’s minor league affiliate at San Angelo (Texas) in the Class-D Sophomore League. (Can you imagine playing in a league called the Sophomore League?)

It was there that Stargell discovered a different world, one more antagonistic toward African Americans. Since many hotels, particularly in the South, did not permit Black guests, Stargell sometimes slept in cots on the back porches of private homes owned by other African Americans. Restaurants also discriminated against Black patrons. Stargell often had to wait in restaurant kitchens, where he was handed scraps of food. At other times, Stargell had to sit on the team bus while the white players ate comfortably in a roadside diner.

The severe racial hostilities that Stargell and other Black players experienced left the slugger feeling understandably bitter, at least early in his career. He also felt worried for his safety. On one occasion, a white man threatened Stargell with a shotgun. The man told Stargell that if he dared to hit successfully in the game that night, he would shoot him. “I couldn’t understand how the color of my skin could make people hate me for something I had never done,” Stargell recalled in the Herald American.

Stargell overcame the racism to make his major league debut in 1962. At six feet and 225 pounds, Stargell was a massive but surprisingly mobile outfielder. He also showed a powerful throwing arm, particularly for a left fielder. At the plate, he showed flashes of promise. Yet, he really didn’t begin to commit himself to the game until after he suffered a disappointing 1968 season, when he batted a meager .237 with 24 home runs. While Stargell could have pointed to the general malaise of the Year of the Pitcher, he chose to place the blame on himself. “I wondered if all I wanted to be was a player who stayed around for 10 years and didn’t really accomplish anything,” Stargell told Baseball Digest, “or did I want to make myself a real good ballplayer, an outstanding ballplayer? Once I used to think that all there was to this game was to show up at the ballpark a couple of hours before game time, go through the usual routine, play nine innings, and go home.”

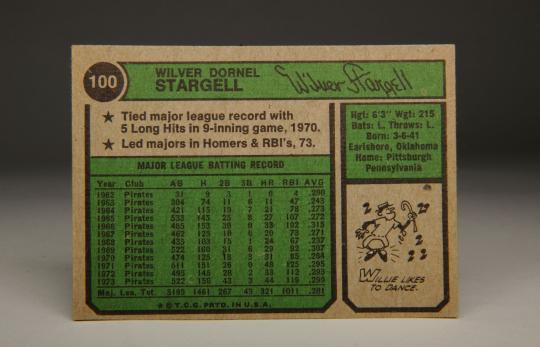

Stargell began to hit more consistently in 1969 and ’70, but it was not until 1971, after an off-season trip to Vietnam, that he became a national star. After reporting to Spring Training in the best condition of his career, he enjoyed a torrid first month of the season, making a successful run at the April home run record. By the end of the month, he had clubbed 11 home runs, including a pair of three-homer games. For the season, Stargell would hit a league-leading 48 home runs and finish second in the MVP voting, pushing the Pirates to a world championship in 1971.

As he made the transition to stardom, Stargell continued to learn about leadership from his teammate, Roberto Clemente. He observed Clemente’s work ethic, including a practice regimen in which he tried to throw a ball from right field into a garbage can situated at third base. Eight years after the Bucs’ world championship, and long after the passing of his friend Clemente, Stargell led the Pirates to another title. In the year of “We are Family,” no Pirate was more prominent than Stargell. The unquestioned leader of the 1979 Bucs, he became a role model and father figure to his teammates, most of whom were 10 to 15 years younger than him. By then, Stargell had established the practice of handing out “Stargell Stars” to deserving teammates. The players then attached the stars to their caps as a reward for their contributions to victory.

Stargell practically willed the Pirates to that championship in 1979. After sharing MVP Award honors with Keith Hernandez during the regular season, he hit .455 with two home runs in the National League Championship Series, winning the MVP award again. And then he completed the MVP trifecta in the World Series, where he tormented the Baltimore Orioles to the tune of a .400 average and three home runs. Stargell became the first (and to date only) player to sweep the three MVPs in the same season.

Stargell’s home runs didn’t just happen frequently; they achieved lengths that had not been seen in decades. Stargell revitalized interest in tape-measure home runs, some of the longest the game had seen since Mickey Mantle’s prime in the 1950s. Stargell’s resume of home runs included two that he launched completely out of Dodger Stadium, known as an extreme pitcher’s park. During Stargell’s career, no other player even managed to hit one home run out of the ballpark in Chavez Ravine.

As much as lengthy home runs defined Stargell on the field, they only scratched the surface of his overall contributions to the game, including his relationship with teammates and the general public. Unlike some self-centered athletes, Willie knew how to connect with fans. After buying a restaurant in The Hill section of Pittsburgh in 1970, he cooked up a special promotion: Every time he hit a home run, the restaurant would give free chicken to anyone placing an order at that moment. The popular giveaway prompted legendary Pirates announcer Bob Prince to proclaim the words, “Spread some chicken on the hill!” whenever Willie blasted another long ball.

Stargell didn’t merely focus his efforts toward patrons of his restaurant. He reached out to all Pirates fans by regularly chatting with them prior to games and willingly signing autographs. For Stargell, this was all part of his regular routine, particularly at Three Rivers Stadium.

People within the game also took notice of Stargell’s willingness to devote time to humanitarian causes. During the 1970-71 off-season, he participated in a USO tour for the benefit of American soldiers fighting in Vietnam. In the Pittsburgh area, he performed volunteer work for the Job Corps and the Neighborhood Youth Corps, working in the ghettos as part of the “War on Poverty.” He became president of the Black Athletes Foundation, an organization dedicated to helping African-American athletes earn better contracts and endorsements while also addressing problems within the Black community.

In perhaps his most well known cause, Stargell served as chief spokesman for the Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation, increasing awareness of a disease that received little publicity in the 1960s. Stargell made numerous public appearances to raise money in combating the sickle cell disease, which attacks blood cells, mostly in African Americans. “So many people know so little about this disease,” Stargell once said in an interview with The New York Times. “These people live a short, miserable life. We need the help of everyone.”

In 1998, only three years before his passing, I was privileged to meet Willie Stargell. In January of that year, during the depths of another Northeast winter, he came to Cooperstown as part of a program put together by the U.S. Post Office. He agreed to speak to a group of children who had assembled in the Hall of Fame’s Grandstand Theater. Although none of those students ever saw him play, they were still captivated by his ability to inspire with his words. In spite of the generational gap, he was able to reach those kids, just as he had always reached me, starting with those days when I collected his cards and imitated his swing.

After Stargell’s talk, I was privileged to be included in a lunch with Willie and several other Hall of Fame staff members. For the first and only time, I had a chance to speak to Stargell face to face. On that day, that 1974 Topps card came full circle for me. I had met the man who had indirectly taught me an important lesson. Of course, I was too embarrassed to tell him about that. I was just happy about meeting a hero.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame