- Home

- Our Stories

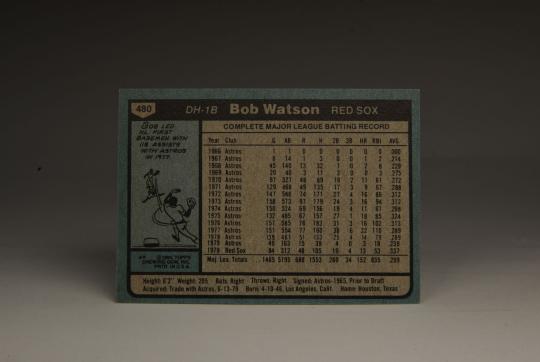

- #CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bob Watson

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bob Watson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Living in Cooperstown, one never knows when one will run into a former major league star. It can happen at any time, in the Hall of Fame Library, at the corner of Main and Pioneer streets, or at the Otesaga Resort Hotel. One of those encounters happened to me at the latter location, back in the fall of 2010, when I was asked to conduct a village trolley tour for friends and family of the great Hank Aaron. The tour began at the front entrance to The Otesaga, a four-star hotel located at the base of Otsego Lake.

On this particular day, I was told that there would be no former major leaguers on the tour, so I was surprised by who I would soon meet. I did not see Aaron at the trolley—he decided to remain at the hotel—but I happened to run into another player, one who was an All-Star first baseman/outfielder and made a name for himself in the 1970s.

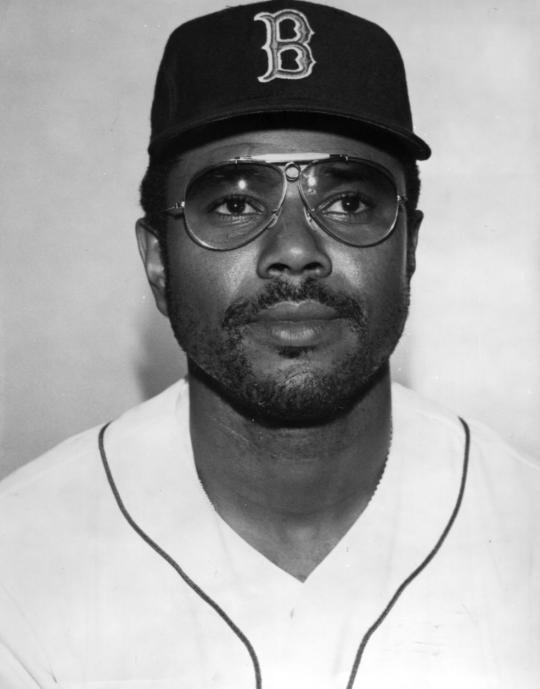

This player, a friend of “Hammerin’ Hank,” was standing right outside of the trolley door. I didn’t recognize him at first, but he did look vaguely familiar. I thought that he might be a retired player, but I could not place a name with the face. Then I saw someone approach him, exclaiming, “Hey, Bob.” At that moment, it popped into my head: Bob Watson. The face now jived with memories from some of my old baseball cards. He still had that strong, rounded build, the one that reminded me of his timeless nickname, “The Bull.”

A few minutes after my moment of recognition, Watson took his seat on the right side of the trolley, in the second row, well within my sights. Bob simply blended into the tour, politely asking questions like some of the other riders, but making no mention of his big league experience. He was apparently too modest to draw attention to himself. About midway through the tour, Billye Aaron, the exceedingly cordial wife of Mr. Aaron, pointed out that one of the trolley riders was indeed Bob Watson. She emphasized that Watson had not only played for the Atlanta Braves, Hank Aaron’s primary team, but had also become one of the game’s first African-American executives.

Shortly thereafter, the conversation turned to Bob’s work as the general manager of the New York Yankees, and how he had helped put together the team that won the world championship in 1996. All through the conversation, Bob remained silently humble about his accomplishments.

Watson had resigned as Yankee GM prior to the 1998 season, in part because of his health and the stress of working in New York. Given Watson’s brief but successful tenure as the Yankees’ general manager, it’s easy to forget what he achieved as a ballplayer in the 1970s and 1980s.

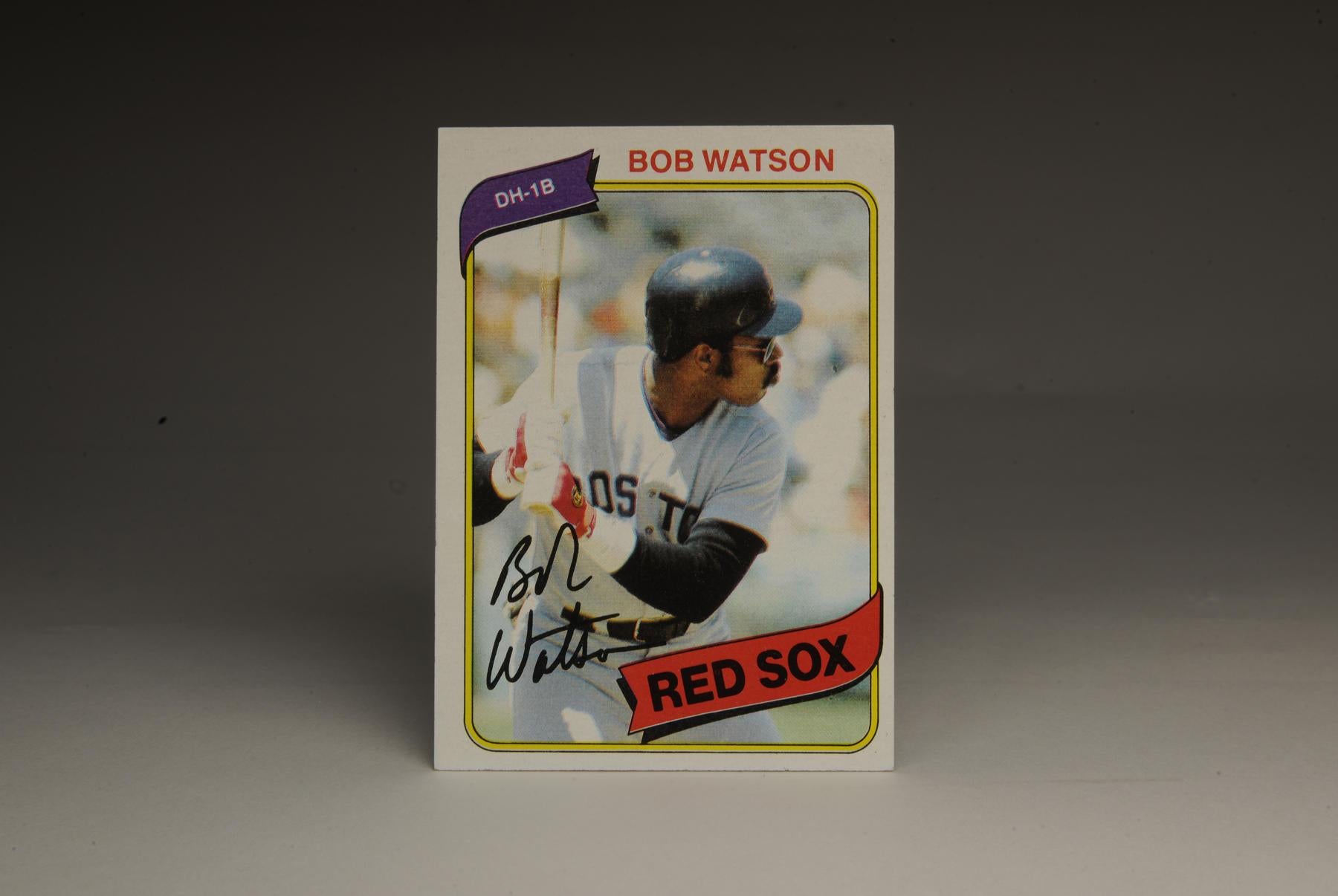

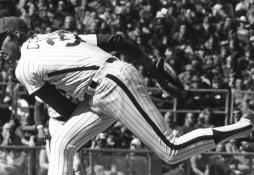

Of all the cards that Topps produced of Watson, I think the 1980 version is my favorite. Taken on a sun-splashed afternoon, the photograph shows him in full action with the Boston Red Sox. While that’s not the team with which he is most identified, the card does very well in capturing Watson’s look in the late 1970s. Everything that I remember about Watson is here: the discernible sideburns, the trademark mustache, and those big wire-frame glasses.

The card also captures Watson’s physique, which was burly, big, and forceful. The nickname of The Bull always fit him well. With batting gloves on both of his hands, Watson appears to have a firm grip on the bat. He wasn’t one to choke up and simply try to make contact. No, Watson wanted full, intense impact when bat met ball.

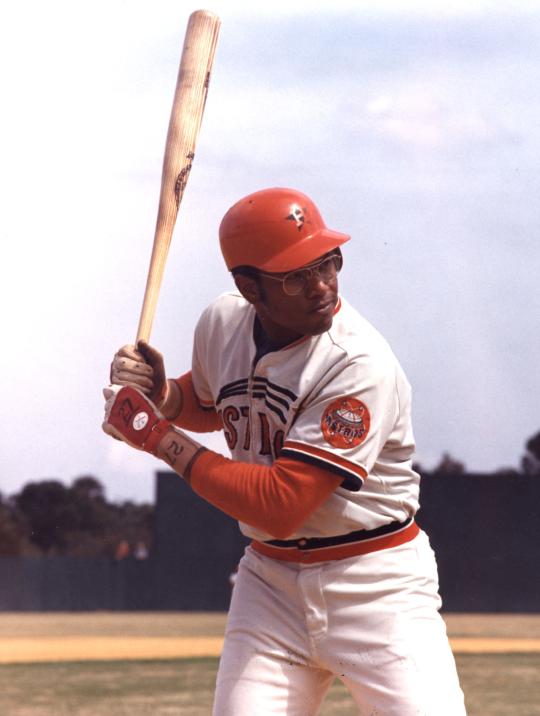

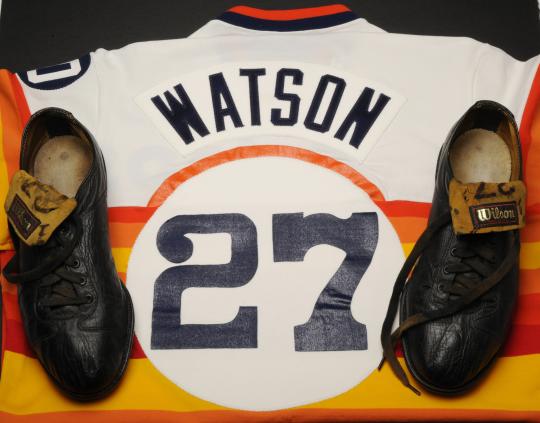

Those who remember Watson’s playing days likely recall him as a power-hitting first baseman, but The Bull actually started out as a catcher in the Houston Astros’ organization. As a young player with the Astros in 1969, he was serving as the bullpen catcher one September day, catching the warmup tosses of a knuckleballing Jim Bouton. With little experience catching the knuckler, Watson ran into trouble. He broke his finger on one of the knucklers and missed the rest of the season. It was an incident that Bouton wrote all about in his bestselling book, Ball Four.

Broken finger aside, Watson struggled with his mobility and his throwing from behind the plate, so the Astros decided to try him in the outfield, at first base, and third base. The Astros intermittently returned him to catching on two occasions, but ultimately settled on him as a left fielder and occasional first baseman. With Watson in left field, the ultra-talented Cesar Cedeno in center, and veteran star in Jimmy Wynn, the Astros boasted one of the game’s best outfields of the early 1970s.

With his large-frame glasses and 200-pound build, Watson looked a little out of place on the ballfield. Yet, his appearance was deceiving. He had incredible strength, especially in his wrists and arms, enabling him to hit line drives into the gaps. He also showed smarts as a hitter, particularly in his ability to take pitches and draw walks.

My early memories of Watson have little to do with his appearance or ability, and everything to do with a baseball gimmick. Playing in a game at Candlestick Park on May 4, 1975, Watson happened to score what was believed to be the one millionth run in major league history, tallying the milestone run just four seconds ahead of Cincinnati’s Dave Concepcion, who had almost simultaneously hit a home run in another game that afternoon. It may be hard to believe, but the one millionth run was a huge deal in 1975; kids talked about it at summer camp later in the year. It was one of the more successful baseball promotions of the 1970s.

Watson received $10,000 (and a million Tootsie Rolls) for scoring the famed run, a good sum of money in the final years before free agency. There is some irony in the celebration of the one milestone run; many years later, baseball historians recalculated the game’s run totals and determined that Watson did not actually score the one millionth run. He was, however, allowed to keep the money—and the Tootsie Rolls.

In reality, the unusual milestone obscured Watson’s capabilities as a well-rounded batsman who could hit for average and power. Another factor that hurt him was his home park, the canyon-like Houston Astrodome, where he had played since making his big league debut in 1966. The Astrodome, dubbed “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” was anything but for hitters, sapping home run and slugging percentage totals. Fans started to appreciate Watson a little better when he moved over to the American League, initially with the Red Sox in 1979. After being acquired to replace the traded George “Boomer” Scott, Watson hit .337 over the second half of the season, and took a particular liking to Fenway Park’s “Green Monster.”

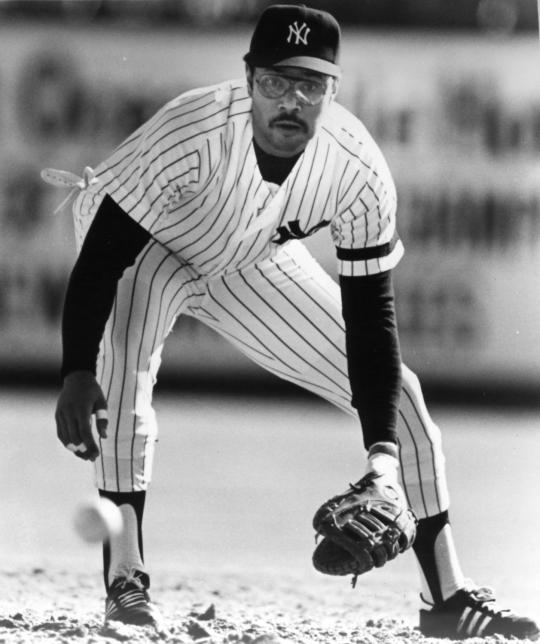

At the end of the ‘79 season, Watson decided to leave Fenway’s friendly limits and cash in his expiring contract for a three-year deal with the Yankees. It was a terrific transaction that directly treated a Yankee need: the lack of right-handed thump. In 1980, Watson became an unconventional but critical part of Dick Howser’s extended platoon system. Watson shared first base duties with Jim Spencer, and served as a designated hitter on other days. Watson handled the transitions seamlessly, batting .307 with a .368 on-base percentage and becoming a key component on a team that won 103 games.

Watson would begin to show the effects of age in 1981, batting a career-low .212 as he turned 34. But he redeemed himself in that fall’s World Series, hitting .319 with two home runs in a six-game loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

After a fitful start to the 1982 season, the Yankees sent Watson to the Braves, acquiring a minor league pitcher named Scott Patterson, who would never make the major leagues. But Watson would return to the Yankees’ organization in October of 1995, when George Steinbrenner hired him as general manager. In one of his first official moves as GM, Watson hired Hall of Famer Joe Torre as manager. That decision alone should place Watson in the pantheon of the most influential of Yankee general managers.

As much success as Watson has had as both a general manager and player, his road has been filled with difficulties. Shortly after signing with the Astros in 1965, he was assigned to the team’s minor league affiliate in Salisbury, N.C. He soon realized that he and two of his African-American teammates could not reside in the hotel with the white players on the team; instead, they were treated like outcasts and taken to the house of a local black man, where they stayed the entire summer.

Later that season, Watson hit a home run and won himself a gift certificate for a free Salisbury steak dinner at a local restaurant. Watson went to the restaurant to collect his meal, but the restaurant owner barred the door, refusing to allow him to enter simply because of the color of his skin.

A different kind of setback occurred in 1993, when Watson was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He had to undergo eight hours of surgery to remove cancerous tumors. The surgery proved successful; Watson has now lived 22 years since the diagnosis.

Watson is retired now, having stepped down from his last job as baseball’s dean of discipline, back in November of 2010.

It’s nice when a piece of cardboard you once collected comes to life, as it did that day in Cooperstown with Bob Watson.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame