- Home

- Our Stories

- Judy Johnson elected to the Hall of Fame

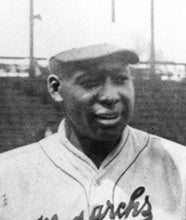

Judy Johnson elected to the Hall of Fame

Though he possessed all the skills of a top-flight player, Judy Johnson was excluded from the major leagues his entire career.

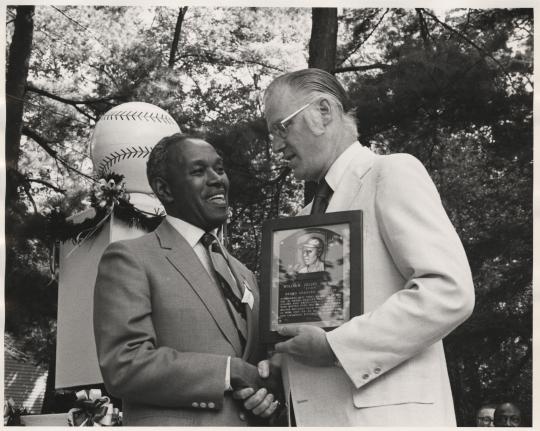

On Feb. 10, 1975, however – 41 years ago this week – Johnson joined one of the most exclusive teams in baseball with his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The Negro Leagues legend became just the fourth third baseman to be honored in Cooperstown, following Jimmy Collins (1945), Pie Traynor (1948) and Frank “Home Run” Baker (1955).

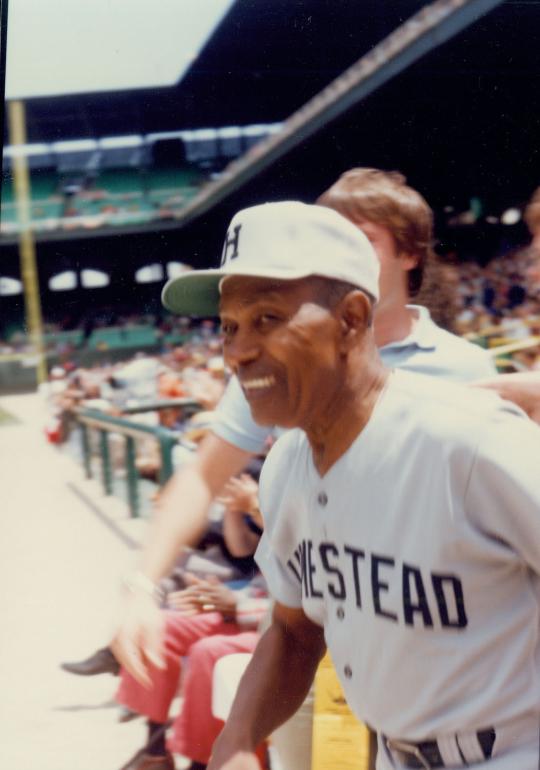

It was a fitting designation for a man named at the top of several polls of Negro League players as the best third baseman they had ever seen. At the time of his election, Johnson’s defensive skills at the hot corner were remembered as equivalent to those of Traynor and Brooks Robinson.

“They couldn’t have compared me to two better men,” Johnson said.

Born William Julius Johnson on Oct. 26, 1899 in Snow Hill, Md. (just 60 miles from Baker’s hometown of Trappe, Md.), he was an undersized boy whose father wanted him to become a boxer.

“Daddy kept telling me I could fight but I knew he was wrong,” Johnson told the press when he was elected. “He made my sister my sparring partner and she used to whale the daylights out of me.”

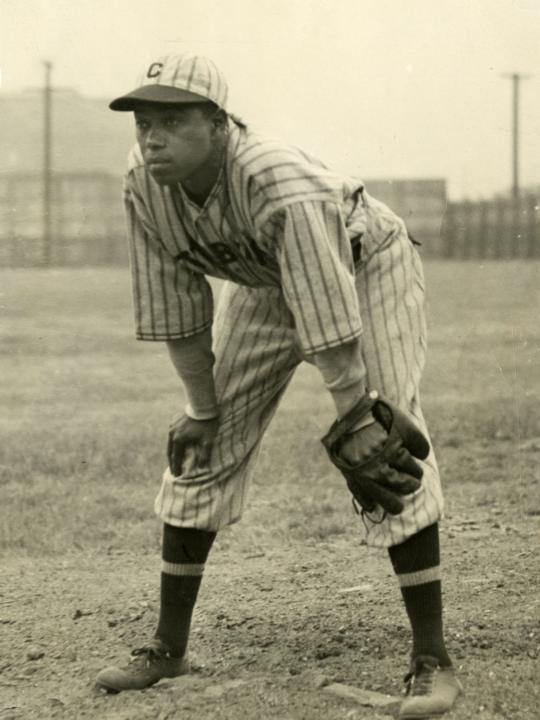

The boy took a much stronger liking to baseball and sought to play professionally in nearby Philadelphia. Weighing about 150 pounds, Johnson was originally deemed too small to play for the Hilldale Daisies, the city’s Negro League team. But under the tutelage of fellow Hall of Famer Pop Lloyd, Johnson played his way onto the team in 1920 and earned his nickname due to his resemblance to Chicago pitcher Judy Gans.

He developed into a line-drive hitter and a defensive stalwart who could stand firm at the bag and make sublime plays look routine. Furthermore, he was widely renowned for his keen observation and intelligence. Later in his career, he would develop a pet play with Hall of Famer Josh Gibson as teammates on the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Johnson, known for being a master at interpreting opponents’ signs, would subtly whistle to Gibson when he sensed he could tag out a runner at third on a pickoff play. Gibson’s quick-draw throw worked like a charm, including one memorable barnstorming contest in which the tandem threw out Leo Durocher.

Barnstorming was how Johnson grew his legend outside the lines of Negro League play. Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack once said that if Johnson were white “he could write his own price” on a major league contract.

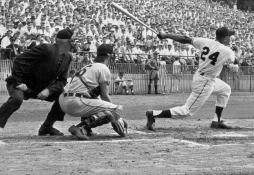

He was sensational in the summer of 1924, when he combined a .324 average with his usual stellar defense to lead Hilldale to its second straight Negro American League title. That fall, the Daisies squared off against the Negro National League champion Kansas City Monarchs in the inaugural Negro World Series.

The Monarchs – led by Hall of Fame pitchers José Méndez and Bullet Joe Rogan – eventually prevailed in 10 games, despite Johnson leading all batters with a .364 average. His hits included six doubles, a triple and a thrilling inside-the-park home run that won Game 5. Hilldale would get the last laugh the following year, when Johnson batted .392 during the season and led the Daisies to a three-games-to-two triumph over K.C. in a rematch.

Johnson was named the Negro League Most Valuable Player in 1929 and would win one last crown with Pittsburgh in 1935 before retiring the following year. In 1954, the Philadelphia Athletics hired him as a temporary coach for Spring Training, making him the first African-American to coach in any capacity in the major leagues.

The man known for his vast baseball acumen would later scout for the Braves, Phillies and Dodgers, counting Dick Allen and son-in-law Bill Bruton as some of his greatest finds. Some believe his knowledge dictated that he should’ve served a greater leadership role on major league fields.

“He had the ability to see the qualities, the faults, of ball players and have the correction for them,” recalled fellow Negro Leaguer Ted Page. “Judy should have been in the major leagues 15 or 20 years as a coach. He was a scout, but he would have done the major leagues a lot more good as someone who could help develop players.”

Johnson never carried ill will toward those who barred him from major league fields, saying “You have to take life in stride. Sometimes your heart might ache, but you can’t let it get you down. There’s always a better day coming.”

Judy Johnson was as deserving as anyone when he became the sixth Negro League player enshrined in Cooperstown.

“I felt so good, I could have cried,” Johnson said of his election. “I’ve been to the Hall of Fame before. But this time it will be different.”

Matt Kelly is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum