“It is wonderful for a man to break a record that has stood for 20 years, especially in the face of the fact that American League pitchers have been working their hardest against him all season and passing him almost every time he was up there in a pinch.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- The Babe of Fenway

The Babe of Fenway

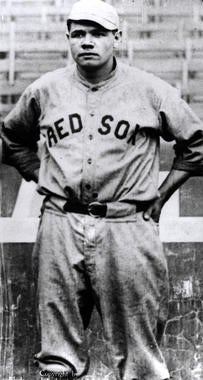

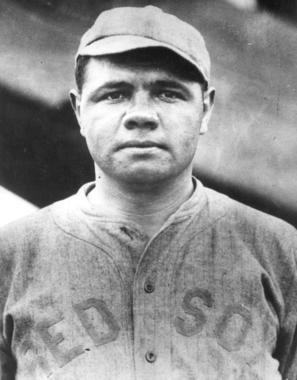

Babe Ruth is one of the National Pastime’s most iconic participants, a name as recognized today as it was during his playing prime almost a century ago.

While his exploits with the New York Yankees are well documented, it was Ruth’s time as a member of the Boston Red Sox – where he spent the first six of his 22 big league seasons – when he first captured the imagination of baseball fans.

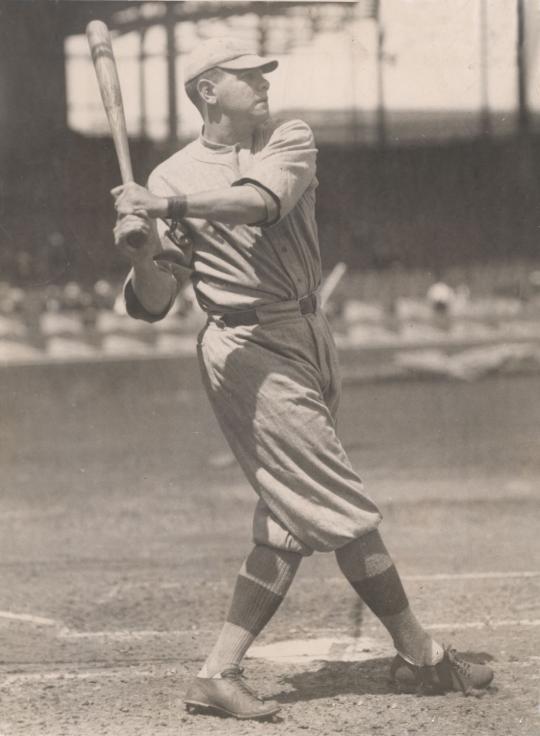

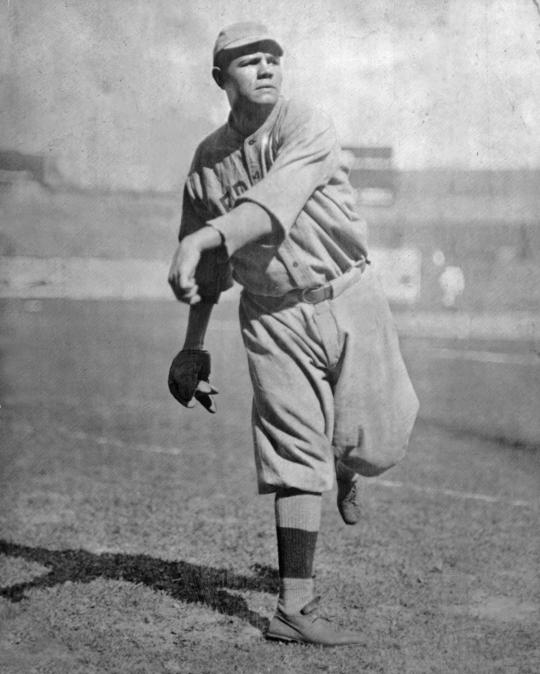

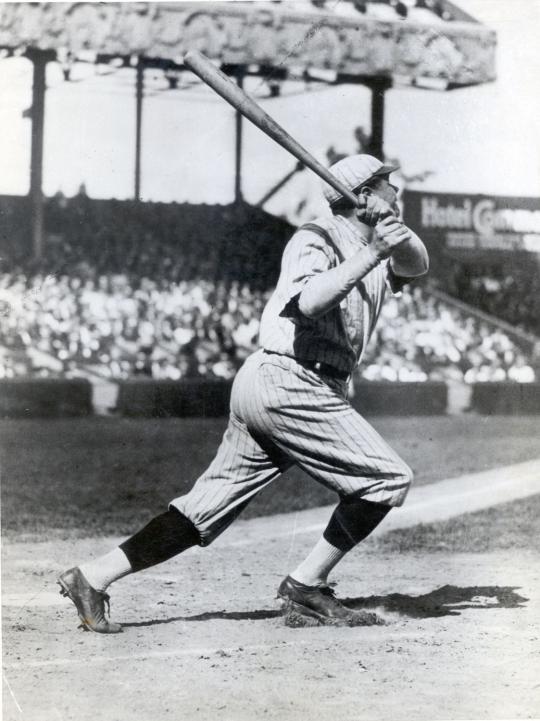

Ruth’s lasting legacy, as evidenced by being one of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s inaugural class of electees in 1936, can certainly be tied to the damage he could inflict with a bat in his hand, demonstrated best by the left-handed hitter’s longtime grip of the game’s single-season and career home run records. But the Baltimore native, raised from the age of seven at the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, first made a name for himself while with the Red Sox as one of the game’s top southpaw hurlers, averaging almost 20 wins a season in the mid-1910s, before making the transition to slugging right-fielder.

And it was at Fenway Park where many of Ruth’s early herculean feats were achieved.

As Fenway Park rolls through its second century, we take a look at Ruth’s most memorable moments at the fabled ballpark, where he not only played 330 regular season games – for both the beloved home team as well as its most hated rival – but also a pair of World Series contests.

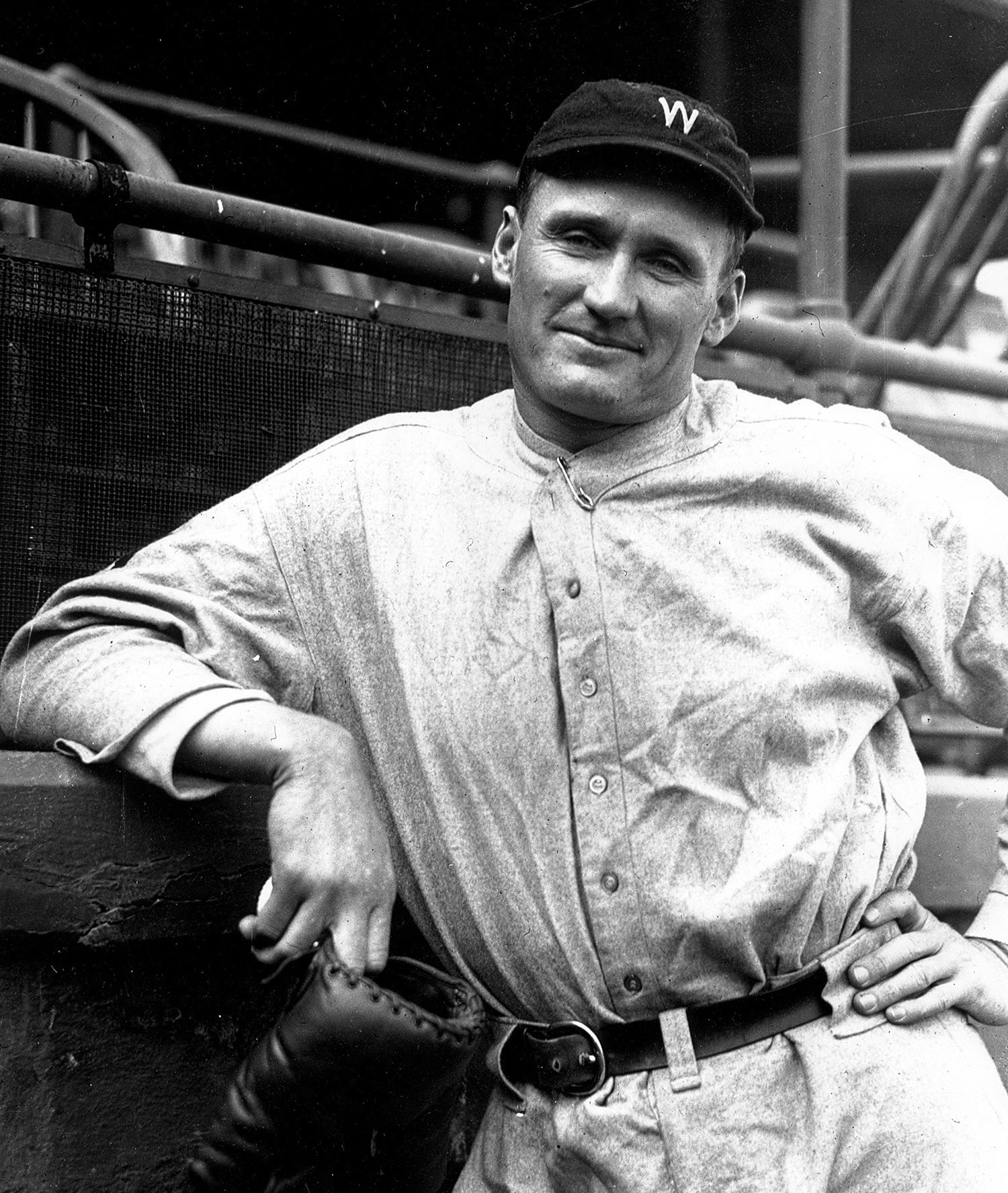

August 15, 1916

Ten weeks after tossing a 1-0 complete-game shutout against fireballing Walter Johnson and the visiting Washington Senators, Ruth turned the trick again at home for the Red Sox, the defending World Series champions, only this time with a 13-inning gem against the squad from the nation’s capital. A scoreless duel for 12 frames by the two future residents of Cooperstown was broken up in the bottom of the 13th when Jack Barry scored from third base on a two-out single to center field by Larry Gardner, his third hit of the game.

One of a league-leading nine shutouts for Ruth, he would end the two hour and 37-minute game having given up eight hits and three bases on balls while striking out two in 13 innings. Johnson, who according to Ruth was “the greatest pitcher I ever saw,” would surrender seven safeties and five walks while fanning five in 12 2/3 innings.

Both hurlers were in the midst of wonderful campaigns, the 28-year-old Johnson ultimately leading the American League with 25 wins, the seventh in a streak of 10 consecutive seasons of at least 20 victories. Ruth, then only 21, would finish with 23 victories and an AL-leading 1.75 ERA to help his team to their second straight Fall Classic title.

“Every once in a while, a young baseball writer will write that I wasn’t a pitcher but a thrower,” Ruth once said. “I read not so long ago that I didn’t bother with signals; I just had a strong and powerful arm and tried to blow down the hitters throwing the ball past them.

“Maybe so, but how do they think I got that 1.75 earned run average and finished ahead of Walter Johnson, Ernie Shore, Coveleski, Carl Mays, Joe Bush and Bob Shawkey? What’s more, in 1916 the American League was a very tough league. It was just before the clubs began losing players to the services and just after they took back the Federal League jumpers.”

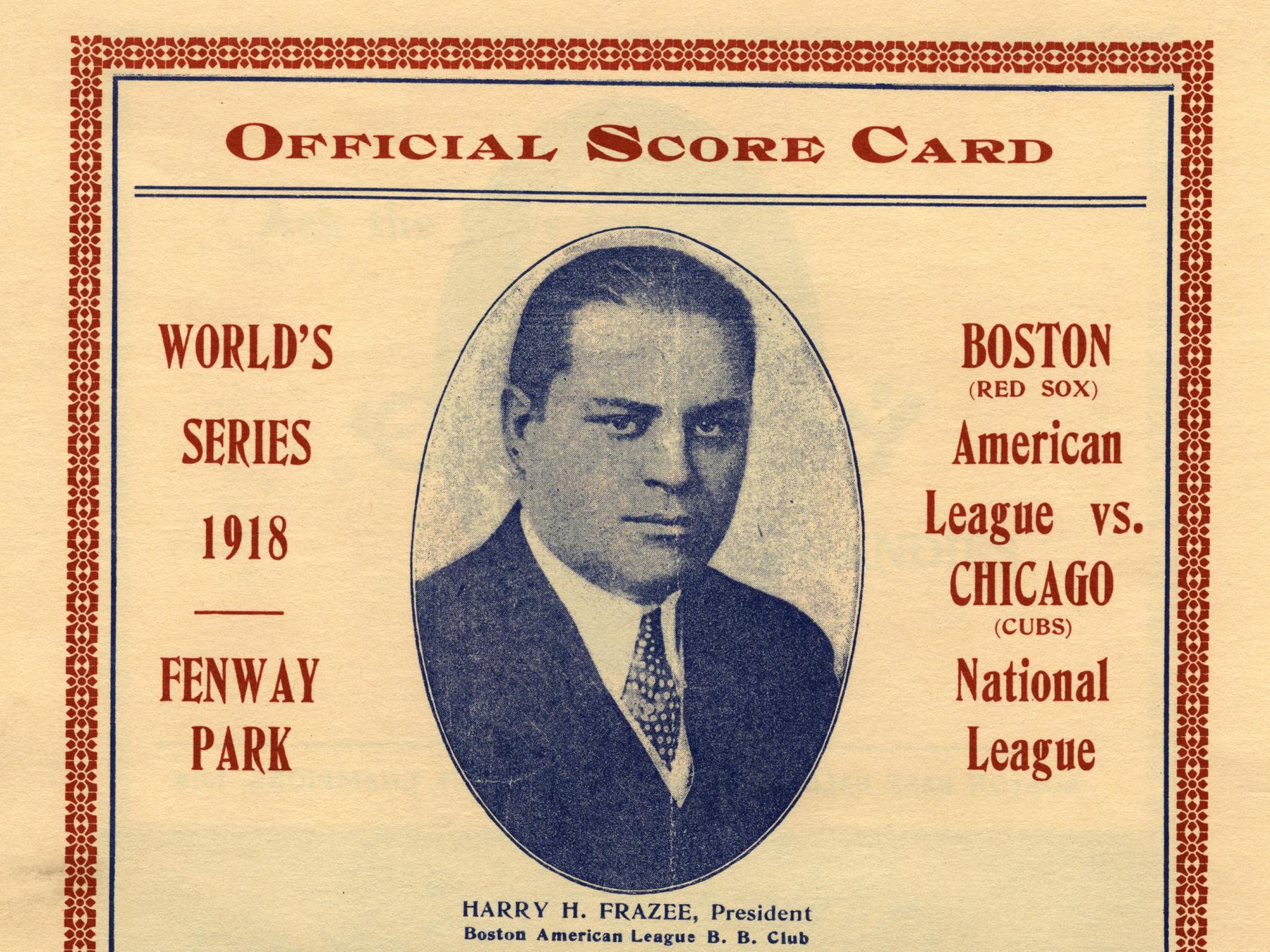

September 9, 1918

“George Tyler didn’t know until it was too late that with Babe Ruth at bat, it is better to check him up for one base on four balls than three or four bases on one,” began sportswriter J.V. Fitz Gerald’s story on the Red Sox’s Game 4 victory at Fenway over the Chicago Cubs in the 1918 World Series. “With two out in the fourth, two on and the count three balls and two strikes on the Baltimore lad, Tyler put one over the plate. The ball never reached Bill Killifer’s mitt. Ruth met it with his bat and sent it on an excursion trip toward the bleachers. The clout was good for three bases and two runs, enough to yield the Red Sox a 3 to 2 victory.”

While Ruth’s triple caused a frenzy among the 22,183 fans inside Fenway Park, helping to give the home team a three games to one advantage on the way to a championship, it should also be noted that the left-hander’s consecutive scoreless innings streak in World Series mound action came to an end at 29 2/3 innings. Today, the record is held by fellow Hall of Famer Whitey Ford, who went 33 2/3 scoreless innings, stretched between the 1960 and ’62 World Series, for the Yankees.

“I pitched in three games in two different World Series and I won all of them. This is not a bad record in itself, for I can tell the world it’s no cinch winning a World Series game,” said Ruth. “But the best thing about it from the standpoint of records was the shutout innings I pitched.

“There’s a satisfaction in standing out there in the center of the diamond and fooling the batters, perhaps burning them past in front of their noses, that you can’t get in any other way.”

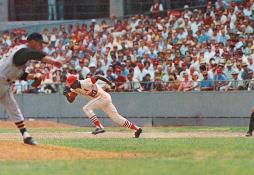

September 20, 1919

In what turned out to be the last day Ruth would wear a Red Sox uniform in front of the home crowd, the future home run king would make some 31,000 fans “howl madly.” In what was billed as “Babe Ruth Day,” sponsored by the local Knights of Columbus, the part-time hurler and full-time slugger was the starting pitcher in the first game of the doubleheader. Though he would come away with a no-decision in his 5 1/3 innings of work against the now-infamous Chicago White Sox – who would later that season win the AL pennant before being accused of throwing the World Series – it was Ruth’s record-tying solo home run high over the left-field scoreboard in the bottom of the ninth inning that gave the defending Fall Classic champions a 4-3 win.

Ruth’s game-winning homer, his 27th of the year, tied the single-season major league record set by Ned Williamson of the National League’s Chicago White Stockings in 1884. The “Babe Ruth Day” celebrations had been planned for between the innings but once he stepped on home, the festivities started immediately as local organizations showered him with gifts and trophies to honor his memorable season.

Ruth would end 1919 with a major league-best 29 round-trippers; Gavvy Cravath of the Phillies next with 12. Williamson had passed away in 1894, but another 19th Century star, Buck Freeman, who clocked in with 25 homers for the Senior Circuit’s Washington Senators in 1899, was amazed at Ruth’s prodigious output that year.

“I congratulate Ruth on his great work,” Freeman said. “It is wonderful for a man to break a record that has stood for 20 years, especially in the face of the fact that American League pitchers have been working their hardest against him all season and passing him almost every time he was up there in a pinch.”

June 23, 1917

Certainly not a highlight of Ruth’s career, but it may go down as one of his memorable big league appearances. The starting pitcher in the first game of a doubleheader against the Senators at Fenway, he walked the game’s leadoff batter, Ray Morgan. So infuriated was he with the work behind the plate by umpire Clarence “Brick” Owens, Ruth threatened the arbiter before striking him behind the left ear with his right hand.

“Three of the four balls should have been strikes,” Ruth recalled years later. “I growled at some of the early balls, but when Owens called the fourth one on me I just went crazy. I rushed up to the plate and I said, ‘If you’d go to bed at night, you so-and-so, you could keep your eyes open long enough in the daytime to see when a ball goes over the plate!’”

After Ruth was dragged off the field by several policemen, Ernie Shore was brought in from the bullpen. Morgan was promptly thrown out at second base in a steal attempt, with Shore proceeded to retire the next 26 consecutive batters in the 4-0 no-hit victory.

After the game, AL President Ban Johnson was quoted as saying, “I’ll take care of Mr. Ruth.” A week later it was announced that Ruth would be suspended for a week and fined $100, a hefty amount for the time.

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum